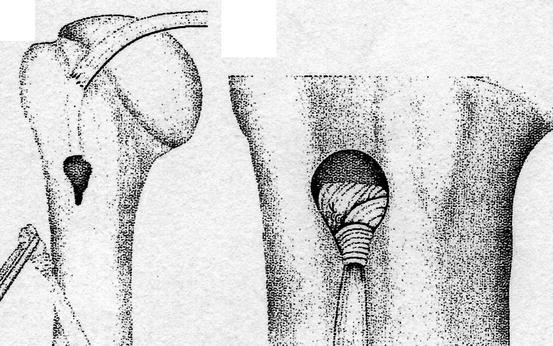

Fig. 16.1

Ultrasound image of a torn rotator cuff

16.1.6 Organ-Specific Imaging

16.1.6.1 Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography

In unclear cases it can be useful to obtain a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan in order to reach a definitive diagnosis or for consideration of differential diagnosis (e.g., in cases of rotator cuff rupture). A distinction can be made between acute and chronic changes and an opinion formed on the issue of previous damage. Computed tomography (CT) for tendon injuries is the absolute exception.

16.2 Special Tendon Injuries and Damage to the Upper Extremity

Rotator cuff

Proximal/distal biceps tendon

Triceps tendon

Tendons in the muscles of forearm and hands

Tendon injuries to the upper extremity are relatively frequent and their cause becomes increasingly traumatic as we move in the proximal-distal direction. Tendon injuries in the forearm and hand region are generally caused by direct mechanisms, in particular by cuts. In contrast, the majority of the lesions of the rotator cuff and long biceps tendon results from degenerative changes caused by overstrain injuries (e.g., in individuals who undertake heavy, physical work).

Isolated traumatic ruptures to parts of the rotator cuff tend to be infrequent but can occur through mechanisms that suddenly increase the distance between the origin and insertion of the muscle belonging to it [1, 2]. This is feasible, for example, in anterior shoulder joint dislocation where a tear in the supraspinatus tendon or alternatively a bony rupture in the greater tubercle can occur. Rupture of the long biceps tendon, on the other hand, is caused almost exclusively by local wear with extensive degenerative changes in the region of the bicipital groove. In contrast, most ruptures of the distal biceps tendon are the result of indirect trauma. They regularly occur because of a violent force applied to the forearm when the elbow is bent and the biceps contracted. Rupture of the triceps tendon is rare (e.g., in power athletes and through indirect mechanisms after local cortisone injections or caused by direct blunt force trauma when the tendon is contracted).

Ruptures of the tendons in the forearm extensor and flexor muscles are caused either by local cuts, such as in the context of suicide attempts or, on occasions, by contusions with substantial soft-tissue damage or in the context of industrial or road traffic accidents. The latter typically involve different types of stab wounds or cuts to the hand. Rupture of the extensor tendon in the region of its insertion at the base of the distal phalanx of the middle finger and rupture of the extensor pollicis longus muscle in the thumb region are caused by degeneration.

The symptoms of tendon rupture at the upper extremity range from the typical signs of a fresh lesion with swelling, hematoma, pain, and loss of function to a complete absence of these characteristic signs of injury. This applies to the creeping occurrence of a rotator cuff rupture and to tears of the long biceps tendon, symptoms of which many patients initially perceive as a kind of strain. Rupture of the distal biceps tendon behaves differently. It is accompanied by swelling, pain, and deterioration of function or lack of strength when the elbow joint is bent. Direct gaps in the course of the tendon in the distal forearm or region of the hand and fingers as a rule inevitably lead to loss of function in the dependent target organ, but are often not recognized in the primary diagnosis. Before initiating any treatment, it is important therefore to test the function carefully for all cut injuries in which depth and extent are unclear.

The threatening complication of re-rupture should be taken into account in all tendon injuries, whether conservatively or surgically treated. Re-rupture is caused by the reduced ability of bradytrophic tissue to heal and by degenerative changes that may be present. In the case of open tendon injuries to the hand and fingers, inflammation of the tendon sheath can develop. Finally, loss of function occurs regardless of correct and complete tendon reconstruction because of local scar tissue formation or long immobilization.

16.2.1 Diagnosis

16.2.1.1 Recommended Diagnostic Measures in Accordance with the European Standard

Inspection: swelling, hematoma, impaired function, change in muscle contours

Palpation: pain on pressure, gap in the continuity of the tendon

16.2.1.2 Further Useful Diagnostic Procedures

Ultrasound: imaging of the localization, extent, and type of tendon rupture (acute/chronic, transverse/multilevel, complete/incomplete) and extent of edema/hematoma.

Radiographs: to exclude bone involvement (bone rupture). To assess any concomitant joint damage (e.g., rotator cuff lesion, rupture of the long biceps tendon).

MRI: with an unclear ultrasound diagnosis. Reproducible, gives more detailed information.

CT: only in exceptional cases (e.g., in cases of concomitant bone injury at the joints).

16.2.2 Treatment

16.2.2.1 Conservative Treatment

Recommended Therapeutic Measures in Accordance with the European Standard

The more acute and fresh the injury to a tendon in the upper extremity, the more pressing is the indication for surgical care. Ruptures of the rotator cuff are treated conservatively because of advanced wear phenomena, especially in elderly patients and particularly if the opposite side exhibits similar changes (ultrasound). Ruptures of the long biceps tendon are also the domain of conservative treatment in older patients. This also applies to proximal ruptures of the biceps tendon, which are chronic or diagnosed late. Various studies comparing conservative and surgical therapy with appraisals of the criteria of pain, strength, and mobility demonstrate only slight superiority on the part of surgical treatment [1–3].

Rupture of the extensor tendon at the distal phalanx is regularly treated conservatively and successfully. Special finger splints are used that hold the distal phalanx in overextension for 6–8 weeks [1].

With partial rupture of the superficial layers of the rotator cuff and degeneration-induced tears in elderly patients with a low degree of activity and where the lesion is no longer fresh, conservative, early, functional therapy can yield good results. Conservative management of ruptures to the long biceps tendon likewise involves early functional therapy during which strong exertion should be avoided in the initial weeks. A conservative therapy regime for injuries to the extensor tendons of the finger using synthetic splints for 6–8 weeks requires them to be worn continually; otherwise partial healing of the tendon can occur with a residual decrease in extensibility.

16.2.2.2 Surgical Treatment

Recommended Therapeutic Measures in Accordance with the European Standard

Fresh, traumatic rotator cuff rupture is a clear indication for surgical reconstruction. A basic distinction is made between technically demanding arthroscopic refixation of the affected part of the tendon and the open procedure, known as “mini open repair” via a “lateral deltoid split”. If there is any doubt, open repair to restore continuity should be preferred. The affected part of the rotator cuff can be re-anchored to the insertion site of the aponeurosis at the greater tubercle either by the transosseous refixation, which is considered reliable or by means of what are known as suture anchors, which are fixed in the bone at the insertion site or somewhat medially of the insertion site. In older or chronic ruptures, the retracted tendon stumps are treated in the same way after mobilization. Special suturing techniques are used. It is important to perform refixation without tension being too great; possibly with medialization of the insertion region. Various graft replacements are used with significant defects or degeneration-induced massive ruptures, such as those involving the deltoid or latissimus dorsi muscle [1, 2]. After completion of all reconstructive measures, temporary immobilization and a physiotherapy program involving a defined increase in mobility and building up of the muscles is necessary (Figs. 16.2 and 16.3).

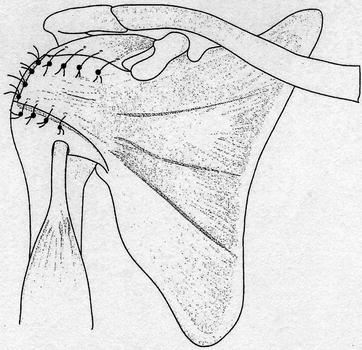

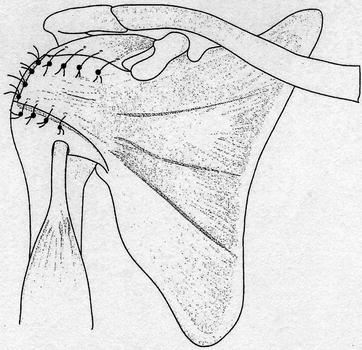

Fig. 16.2

(a, b) Arthroscopic technique of transosseous suture in rotator cuff tears

Fig. 16.3

Transosseous fixation of the torn rotator cuff at the site of the greater tubercle. (a) Incision. (b) Mobilization of the tendon. (c, d) Transosseous fixation

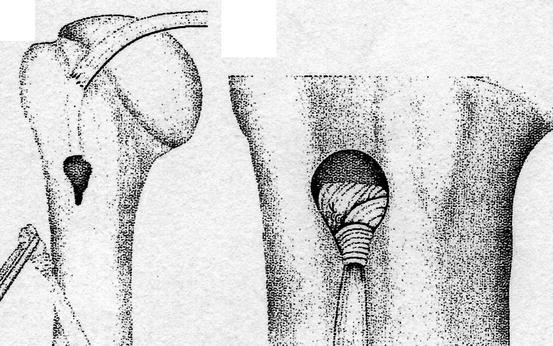

Ruptures of the long biceps tendon are managed for the given indication by using the keyhole technique (Fig. 16.4). The distal end of the tendon is located and used to form a knot that is secured with a suture. Subsequently, with the elbow joint at 90°, a hole about 8 mm in diameter is drilled in the bone of the upper arm after the tendon/muscle has been sufficiently tensed. The drill hole is extended distally to form a slot. The knotted tendon is fitted into this “keyhole” [3, 4]. Concomitant and follow-up management includes early mobilizing physiotherapy. Alternatively, the tendon stump can also be connected to the short head of the biceps using Kessler-type sutures or can be anchored at the coracoid process. Concomitant and follow-up treatment includes early functional rehabilitation.

Fig. 16.4

Transfer of a m. subscapularis flap into the defect of the rotator cuff

Anatomical reinsertion is performed at the radial tuberosity in distal biceps tendon rupture. Transosseous reinsertion via V-shaped drill holes is time-consuming, and recently, the tendon has been re-anchored using suture anchors that were inserted into the tuberosity [5, 6]. Because of potential lesions of the superficial and deep branches of the radial nerve and the occasional development of heterotopic ossification with subsequent reduction in joint function, the complication rate for these interventions is not negligible. Adjuvant and follow-up treatment can be performed as early functional procedures when the tendon has been reliably fixed (Figs. 16.5 and 16.6).

Fig. 16.5

Keyhole technique for re-fixation of the long biceps tendon

Fig. 16.6

Reinsertion of a distal biceps tendon rupture using suture anchors

Cut injuries with tendon involvement in the distal forearm, wrist, or in the hand or finger region are frequent and are treated according to the rules of tendon surgery using special suture techniques and a differentiated adjuvant and follow-up treatment using special functional splints. For loss of substance, tendon grafts or transfers are performed. Rupture injuries to the bone, such as to the extensor tendons, from a certain size and degree of dislocation are refixed using tension band fixation or small screws. Ruptures of the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus muscle, either on the basis of degenerative changes in chronic fractures or iatrogenic fractures of the distal radius occurring on reconstruction, are treated by using an extensor indicis proprius graft.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree