Temporomandibular Disorders

Edgar Fayans DDS

Vague pain relating to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) that resembled otalgia was first described by Costen in 1934. Since that time, temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) have been identified as Costen’s syndrome, TMJ disease, TMJ syndrome, and trigeminal syndrome. Although TMD is mainly treated by dentists, this entity is complex and often requires a multidisciplinary approach. The primary care provider may elect to initiate immediate care and refer cases that recur to specialists. Frequently, patients seek different providers for diagnosis and relief.

TMJ articulation disorders and masticatory muscle disorders appear in the differential diagnosis of headache disorders, cranial neuralgias, and facial pain. Pain in and around the jaw can also be infective, metabolic, neoplastic, systemic, or referred. Diagnosis of jaw pain must progress by first ruling out the most significant or life-threatening findings. Pain from myocardial perfusion insufficiency can radiate to the mandible and be a sole finding (Balchelder et al, 1987). Intracranial and cervical spine lesions can cause pain around the jaw and can have significant consequences if undiagnosed (Polette, 1992). However, most TMDs are not related to these problems.

Pain from TMD of nonneurogenic origin is most often muscular, which may be a contributory factor in tension headaches. Another common origin of pain is the TMJ structure. Lack of concrete, agreed-on diagnostic criteria, however, has led to confusion in diagnosis and management. Patients may be referred from provider to provider in a continuous loop. Primary care providers, dentists, orthopedists, otolaryngologists, neurologists, rheumatologists, chiropractors, anesthesiologists, and acupuncturists all treat patients with chronic facial pain, but most management options are performed by dentists.

Recent literature about and recognition of this condition have brought significant changes in the management of TMDs. Recognition of related disorders has produced advances in management, although in certain patients the diagnosis and treatment are elusive. Common TMDs (especially those aggravated by stress) seem to be cyclic and diminish with age (NIH, 1996). Successful therapy may be simple palliation until symptoms abate and remission occurs.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

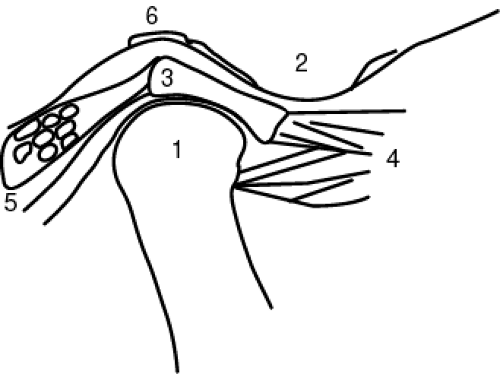

Facial pain relating to TMD may arise from neurogenic sources, muscles, the salivary glands, bone, the TMJ, the vascular system, the pharynx, the tongue, the mucosa, the eustachian tubes and ears, the skin, the teeth, the gingiva, or the ligaments. The following discussion focuses on the bones, the joint, the muscles, and other important structures (Fig. 50-1).

FIGURE 50-1 Anatomy of the jaw: (1) Condylar head, (2) Articular eminence, (3) Disc, (4) Lateral ptyerigoid muscle, (5) Retrodiscal tissues, (6) Glenoid fossa. |

Anatomy

Both jaws—the maxilla and the mandible—have alveolar processes that connect to the roots of teeth with ligaments. The mandible has attachments from all the major muscles of mastication. It articulates with the maxillary teeth (occlusion) and the cranium at the temporal bone’s glenoid fossa, just anterior to the ear.

The TMJ is a unique joint in the body. Unlike others, it has cartilaginous end plates and a hyaline cartilage disc between the bones. The TMJ is composed of a capsule surrounding the cartilaginous head of the mandible, the articular disc, and the articulating temporal bone surface. It has a muscle-assisted interarticular disc that has almost no healing capacity. The disc is mainly fibrous and is attached posteriorly to a superior elastic vascular bed (which produces synovial fluid) and to a ligament-like fibrous band inferiorly (which limits movement forward). The disc is bathed in synovial fluid, which lubricates, hydrates, and protects it from compression, deformation, and shear forces.

Physiology and Pathology

The TMJ slides completely out of its socket over the articular eminence as it translates forward almost two times the anterior-posterior width of the condylar head. The joint is under load even during sleeping hours. Jaw tone, in addition to being constantly adjusted with changes in head position and posture, is highly prone to increased tonus during stress. Microtrauma and repetitive abuse can also lead to significant joint derangement and joint crepitus and noises. If excessive pressure occurs, permanent deformation may cause surface contour irregularities, leading to pain, crepitus, clicking, or other noises. Acute trauma, when not absorbed by injuring the dentition or fracturing the jaw, may cause significant trauma in the joint. This may lead to hemarthrosis, perforations, disc separations, and inflammatory states, which may be temporary or permanent. Inflammation can lead to intersynovial volume increase (synovitis, capsulitis) without reabsorption. Fluid in one joint may increase the distance from the temporal bone and cause a lack of occlusion (space between posterior teeth) on this side and pain.

The ligaments that attach to the mandible and joints do not control movement until the extremes of motion (Posselt, 1989). When the jaw protrudes, the posterior fibrous zone that holds the disc, the temporomandibular ligament, the sphenomaxillary ligament, and the stylomandibular ligament prevent joint laxity. These ligaments, together with muscular tone, prevent dislocation of the jaw. Muscle and ligament laxity may lead to dislocation. The muscles and ligaments act bilaterally

in straight protrusive movements and unilaterally during lateral excursions of the mandible. When going into a lateral movement, the joint on the same side as the jaw is moving rotates as the other joint translates. End points of closure and initial movement of the jaw are guided by planes established by the intermeshing of the dentition. If jaw movement is not synchronized with disc movement, the joint can malalign, causing pain.

in straight protrusive movements and unilaterally during lateral excursions of the mandible. When going into a lateral movement, the joint on the same side as the jaw is moving rotates as the other joint translates. End points of closure and initial movement of the jaw are guided by planes established by the intermeshing of the dentition. If jaw movement is not synchronized with disc movement, the joint can malalign, causing pain.

The musculature is the cause of most TMDs (Sciffman et al, 1989). Joint movement irregularities or joint problems often create resultant myospasm or myositis. Myospasm and myositis often exist with relatively asymptomatic joints. The large elevator muscles (medial pterygoid, masseter, and temporalis) are responsible for the powerful crushing actions of the jaw.

Reflexes, which cause the jaw to snap open when the biting surfaces close into a hard object, synapse from the trigeminal spinal tract nucleus to the motor nucleus without any cortical input and cause sudden changes in muscle tone. A current explanation of the TMD condition is that it may be caused by brain stem inflammation along these tracts. Muscles also suddenly relax during the yawn reflex. Overstretching of muscles has been demonstrated to be an etiology in myospasm. The identifiable painful area in a muscle is often not the area that is in spasm; this is called a trigger point. Myospasm can occur because of protective muscle splinting. This muscle guarding is often a response to avoidance of a painful input.

Patients with persistent overuse of the masticatory muscles may demonstrate muscular hypertrophy. This is evident mainly in the masseter and temporalis muscle. Dental etiology should always be ruled out. Occlusion may cause disruption of normal biting. Premature contacts of teeth (teeth that do not allow the joint to settle completely in the fossa) can cause disharmony of the joint and musculature. The patient should be questioned as to the date of the last dental visit to rule out prosthetic dental interference. Continuous muscle splinting and other parafunctional habits can cause pressure spots in the joint apparatus and pain. Bruxism, the continuous intermeshing of teeth under force, usually at night, can overload the normal physiologic homeostasis of the joint.

Spasms in the stylohyoid and digastric muscles occur with some frequency and can mimic the symptoms of submandibular lymphadenopathy. Muscles in the soft palate or ligaments near the joint can cause abnormal pressures on the eustachian tube, causing altered hearing or “clogging” of the ears. Perhaps the most common muscles to go into spasm and demonstrate pain are the masseter and the lateral pterygoid. The lateral pterygoid probably is responsible for disc and capsule movement, along with the initiation of movement of the mandible in opening. Because this muscle is short, powerful, and deep, pain here is not easily localized to its origin. When the masseter or temporalis goes into spasm, the patient can more easily identify the site of pain. Traction of the lateral pterygoid on the joint (from spasm) can cause otalgia. Incoordination of this muscle has been implicated in joint noises as well as deviation in the uniformity of jaw opening. If the lateral pterygoid suddenly contracts strongly when the jaw is initiating its closure stroke, a sudden anterior disc displacement can occur, causing acute pain, a popping noise, and malocclusion.

Drugs such as butyrophenones, phenothiazines, levodopa, anticholinergics, antihistamines, amphetamines, and cocaine have also been implicated in acute-onset jaw pain, deviations, and malocclusions. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been implicated in clenching, which may be resolved by dose adjustments or the addition of buspirone to the regimen (Ellison & Stanziani, 1993).

Other etiologies for TMDs can be from many sources. Neurogenic pain such as trigeminal neuralgia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, and postherpetic pain are well documented but have unique presentations. Burning, throbbing pain of the mouth and surrounding structures can have several etiologies. This pain, if not fungal or the result of vitamin deficiencies or an allergic response, may be related to the sympathetic nervous system’s effect on vascular beds.

Salivary gland dysfunction may relate to arthritis (Sjögren’s syndrome); as a whole, TMDs have a much higher prevalence in patients with arthritis. Lyme disease with an arthritic presentation should be ruled out in a TMD workup. Viral infections such as wryneck and mumps may produce symptoms similar to those of TMDs. The patient with severe pain of sinus origin usually has a previous history, point tenderness, positional pain, and congestion. Pain over the temporal artery (overlying the TMJ) should alert the provider to obtain a sedimentation rate to rule out temporal or cranial arteritis, which can swiftly lead to ipsilateral blindness, or central nervous system involvement.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Patients with TMDs number more than 10 million (NIH, 1996). TMDs are difficult to discuss from an epidemiologic viewpoint because of their multiple diagnoses and presentations. Diverse pain conditions such as arthritis, growth disorders, connective tissue diseases, Lyme disease, injuries, muscular disorders, Eagle syndrome, and vascular, neurogenic, dental, salivary, and bone problems complicate any study of frequency and distribution.

Epidemiologic studies suggest a greater incidence in women; however, women are more frequent users of health care in general (Levitt & McKinney, 1994). Peak prevalence of TMDs is in persons ages 20 to 40. TMDs may be self-limiting: the incidence, signs, and symptoms diminish in older age. Clicking or other joint noises or jaw deviation occurs in up to 50% of normal persons (Wabeke & Spruijt, 1994) and may be disregarded if no other symptoms are present. In addition, up to 15% of asymptomatic joints that were silent (no clicking) were found to have joint displacements (Westesson et al, 1989).

Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis can occur in patients susceptible to these diseases, but arthritis rarely occurs only in the TMJ. Patients with progressive TMD do not follow epidemiologic norms. There is little information as to the ethnic and racial prevalence of TMDs. Societal barriers and prejudice may also exist, as in all chronic pain states. Even though signs and symptoms may occur in up to 50% of the population, only a few seek treatment.

Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis can occur in patients susceptible to these diseases, but arthritis rarely occurs only in the TMJ. Patients with progressive TMD do not follow epidemiologic norms. There is little information as to the ethnic and racial prevalence of TMDs. Societal barriers and prejudice may also exist, as in all chronic pain states. Even though signs and symptoms may occur in up to 50% of the population, only a few seek treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree