Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attacks, and Carotid Stenosis

Willem Wisselink MD

Thomas F. Panetta MD

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States. Approximately 2 million people are affected annually, with the highest incidence in elderly men—1440 cases annually per 100,000 men over 75 years old. The estimated yearly cost of stroke disability is $16.8 billion in the United States. Stroke, also referred to as cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or brain attack, is associated with an initial death rate of 15% to 35%. Of those who survive, approximately one third will recover to near-normal function; another third will have residual deficits but can return to work. Twenty-five percent of stroke victims are permanently disabled to a degree that they cannot perform their professional duties; the remaining 6% to 8% require custodial care. Only 50% of patients who suffer a CVA are alive 5 years later, and 25% will have a second stroke, for which the death rate is 62%.

Because of these devastating sequelae, prevention of stroke is a primary concern. Early recognition and treatment of persons at risk may lead to a decreased incidence. Risk factors for cerebrovascular arterial disease include hypertension, smoking, obesity, aging, male gender, and hyperlipidemia. With regard to etiology, a stroke can be ischemic or hemorrhagic. Ischemic strokes, in turn, can be caused by embolization or hypoperfusion. Embolic strokes frequently result from migration of a thrombus from the heart or from an ulcerated lesion in the carotid artery to the brain. Hypoperfusion may result from a tight stenosis in the carotid artery, causing brain ischemia in the corresponding hemisphere. Hemorrhagic stroke, accounting for some 25% of cases, is caused by hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage, ruptured saccular intracranial aneurysm, hemorrhage associated with bleeding disorders, or arteriovenous malformations.

DEFINITIONS

Patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease are usually classified by clinical presentation:

Asymptomatic carotid stenosis

Transient ischemic attacks (TIA)

Reversible ischemic neurologic deficits

Chronic cerebral ischemia

Vertebrobasilar symptoms

Stroke in evolution

Completed stroke.

Patients with hemorrhagic strokes are categorized by the location of the bleeding: intracerebral, subarachnoid, subdural, or epidural.

An asymptomatic carotid stenosis is any preocclusive atherosclerotic plaque in the common carotid artery, the carotid bifurcation, or the internal carotid artery in a patient with no ipsilateral monocular or cerebral hemispheric symptoms. A number of asymptomatic carotid stenoses are detected by the presence of a bruit during simple auscultation of the neck. Alternatively, a patient may undergo a carotid imaging test as part of routine screening or a preoperative workup (eg, a patient who is prepared for coronary artery bypass grafting), or because of contralateral hemispheric symptoms.

TIAs are focal neurologic deficits that resolve within 24 hours. TIAs are quite variable and may cover the entire spectrum of neurologic dysfunction, ranging from complete hemiparesis to just a small loss of sensation in an extremity. Amaurosis fugax (transient blindness) is a type of transient attack in which the patient experiences an episode of monocular blindness, usually described as “a shade coming down over the eye.” During the funduscopic exam, small, bright-yellowish material may be seen in the retinal arteries. Hollenhorst, an ophthalmologist at the Mayo Clinic, first identified these plaques as small emboli consisting of cholesterol crystals, which were most likely to originate from a diseased carotid bifurcation.

Amaurosis fugax in the absence of Hollenhorst plaques can be caused by platelet fibrin complex emboli that have subsequently dissipated, emboli in the choroidal circulation that cannot be visualized on funduscopic examination, or symptomatic low flow states. White, nonscintillating calcific emboli and diffuse pallor of the disc have also been described. Plaques in the retina have been associated with all forms of cerebrovascular disease and are a marker for both systemic atherosclerosis and atherosclerotic coronary artery disease.

Crescendo TIAs are monocular or hemispheric symptoms that resolve within minutes after each episode but increase in frequency, eventually occurring multiple times on a daily basis.

Reversible ischemic neurologic deficits is an obsolete term for symptoms that persist longer than 24 hours but resolve within 72 hours. These patients are now referred to as having sustained a stroke with full recovery.

Chronic cerebral ischemia is a term reserved for patients with less specific symptoms such as lightheadedness, (pre)syncope, ataxia, or even a subjective impression of compromised cerebral function. It is associated with the presence of multiple extracranial cerebrovascular occlusions.

Disease of the vertebrobasilar system can result in any combination of motor dysfunction, sensory loss, homonymous visual field deficits, or, more specifically related to the posterior circulation, loss of balance, vertigo, dysequilibrium, diplopia, dysarthria, and dysphagia.

A stroke in evolution is a neurologic deficit that progresses or fluctuates while the patient is under observation.

A frank stroke is defined as a sudden, nonconvulsive, focal neurologic deficit that is no longer changing and has persisted for more than 72 hours. Hemorrhagic stroke is subdivided into primary intracerebral hemorrhage, believed to originate from arteries weakened by chronic hypertension, and spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage, resulting from a ruptured saccular aneurysm.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

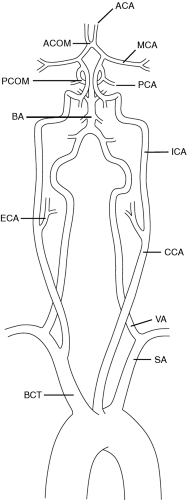

Blood supply to the brain occurs through paired carotid and vertebral arteries, all of which contribute to the circle of Willis. From the circle of Willis, which lies in the subarachnoid space at the base of the skull and is a complete circle in only 30% of people, the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries arise (Fig. 58-1). The carotid bifurcation, by far the most common site of atherosclerotic disease of the extracranial cerebral vessels, is located at the midcervical level (usually between C3 and C4). Occasionally, it may be as high as C1 or as low as T2. The internal carotid artery normally lies posterolateral to the external carotid and can be distinguished by its complete lack of branches in the neck. The vertebral arteries fuse at the base of the skull to form the basilar artery, which in turn gives rise to the posterior communicating arteries.

Anatomic variations include the so-called bovine arch, where the common carotid artery arises directly from the innominate artery (10%), an aberrant right subclavian artery originating distal to the left subclavian artery and passing behind the esophagus (0.5 to 1%), and, less commonly, a right or double aortic arch. Rarely, the internal carotid artery is congenitally absent or hypoplastic. The vertebral arteries may arise directly from the aorta, from various locations of the subclavian arteries, or directly from the carotids. Kinks and coils of the carotid arteries, seen in 10% to 15% of patients, are the result of disproportionate embryonic migration of these arteries in relation to the central nervous system. Unless associated with atherosclerotic disease, kinking and coiling are usually benign conditions and are not related to either age or hypertension.

More than any other organ, the brain depends from minute to minute on an adequate blood supply. If deprived of oxygenated blood for 4 to 5 minutes, irreversible damage occurs in the form of ischemic necrosis or infarction. This common end point, also referred to as softening of the brain or encephalomalacia, can be the result of many different pathologic alterations in the circulation, including atherosclerosis, thrombosis, atheroembolism, fibromuscular dysplasia, arteritis, hypertensive hemorrhage, hemorrhage from intracranial aneurysms or arteriovenous malformations, trauma, and hematologic disorders.

Although atherosclerosis is a generalized process, specific vessels, such as the abdominal aorta and the orifices of its major branches, are particularly susceptible. The superficial femoral artery and the coronary and carotid arteries also are frequently involved. Even within susceptible arteries, certain areas are particularly likely to be affected: carotid plaque is usually confined to the bifurcation of the common carotid artery and the bulbar, proximal area of the internal carotid artery. This is one of the reasons carotid endarterectomy can be relatively easily performed: only a short segment of carotid artery is usually involved, which enables the surgeon to reach “clean” end points proximal and distal to the endarterectomy site.

Thrombosis occurs if flow in a diseased artery decreases to a critical threshold. Emboli may arise from the heart in the form of mural thrombi or valvular vegetations. Mural thrombus may be the result of atrial fibrillation or myocardial infarction. Alternative sources for emboli to the brain are atherosclerotic plaques and ulcers in the aortic arch or the carotid arteries. Fibromuscular dysplasia is a disease that affects mainly women in their third or fourth decade of life and leads to a classic “chain of beads” appearance of the internal carotid artery.

The term “arteritis” covers a mixed bag of disorders, including the connective tissue diseases, such as polyarteritis nodosa, lupus erythematosus, temporal arteritis, and Takayasu disease, and infectious processes, such as syphilis or tuberculosis.

Hemorrhagic stroke may occur as a result of a hypertensive crisis or from rupture of a saccular aneurysm or an arteriovenous malformation. The problem may also lie in the blood itself (bleeding disorders such as thrombocytopenia or the use of anticoagulants and fibrinolytic agents).

Primary (hypertensive) intracerebral hemorrhage occurs almost without exception within the brain tissue itself. Rupture of arteries in the subarachnoid space is unheard of unless aneurysms are present. The extravasated blood forms a roughly circular or oval mass that disrupts and compresses the surrounding tissue and increases in size as the bleeding continues. In the first hours after a bleed, edema accumulates around the clot, adding to its mass effect. If the mass effect is significant, shift of the midline structures and compression of the brain stem may occur, leading to coma and death. A satisfactory explanation as to why these intracerebral arteries rupture does not exist, but rupture is believed to occur in areas in the arteries that have been weakened by the effects of chronic hypertension.

Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage from a saccular aneurysm of one of the arteries of the circle of Willis is the second most common cause of hemorrhagic stroke. Extravasated blood floods the subarachnoid space (in which these arteries reside) and increases intracranial pressure. Because the hemorrhage is confined to the subarachnoid space, there are few or no lateralizing symptoms, which may greatly delay the correct diagnosis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Stroke is generally considered a disease of middle-aged and elderly persons. In the Framingham study (Kiely et al, 1993; Wolf et al, 1983), stroke rates gradually increased with age in men and escalated dramatically after menopause in women. National surveys (Weinfield, 1981) have indicated that no more than 3% of cerebral infarctions occur in patients younger than 45 years. In contrast, however, a recent study evaluating a large number of hospital admission records found that 25% of patients admitted with the diagnosis of cerebral infarction were 50 or younger. A possible explanation is the improved recognition of stroke-related symptoms in young people.

In the United States, stroke incidence has been nearly equally distributed across racial lines; however, African American men have much higher age-adjusted stroke death rates than do men and women of other races. Recently, however, hospitalized stroke was found to be twice as frequent in African Americans compared to whites, both men and women, in a study in northern Manhattan (Sacco et al, 1991). In another study, ethnic differences appeared to reflect the impact of various stroke risk factors in patients with nonhemorrhagic infarcts. The study population was divided into white, African American, or Hispanic patients. Recurrent stroke, death from stroke, or both were most frequent in whites and least frequent in Hispanics, especially in the first year after stroke. Hypertension was more prevalent in African Americans and Hispanics. The incidence of cardiac disease was highest in whites and lowest in Hispanics. Thus, African Americans and Hispanics may have an increased burden of stroke risk factors to account for their increased incidence of stroke. Ongoing case-control and cohort studies are aimed at determining whether these differences persist after controlling for differences in socioeconomic status and access to medical care. Knowledge of the varying effects of risk factors in ethnic groups, however, may raise the level of suspicion and promote more aggressive treatment of such factors in persons of different ethnicity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree