Sinus node arrhythmias

When the heart functions normally, the sinoatrial (SA) node (also called the sinus node), acts as the primary pacemaker. The sinus node assumes this role because its automatic firing rate exceeds that of the heart’s other pacemakers. In an adult at rest, the sinus node has an inherent firing rate of 60 to 100 times per minute.

In approximately 50% of the population, the SA node’s blood supply comes from the right coronary artery, and from the left circumflex artery in the other 50% of the population. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) richly innervates the sinus node through the vagal nerve, a parasympathetic nerve, and several sympathetic nerves. Stimulation of the vagus nerve decreases the node’s firing rate, and stimulation of the sympathetic system increases it.

Changes in the automaticity of the sinus node, alterations in its blood supply, and ANS influences may all lead to sinus node arrhythmias. This chapter will help you to identify sinus node arrhythmias on an electrocardiogram (ECG). It will also help you to determine the causes, clinical significance, and signs and symptoms of each arrhythmia as well as the interventions associated with them.

The 8-step method to analyze the ECG strip will be used for each of the following arrhythmias.

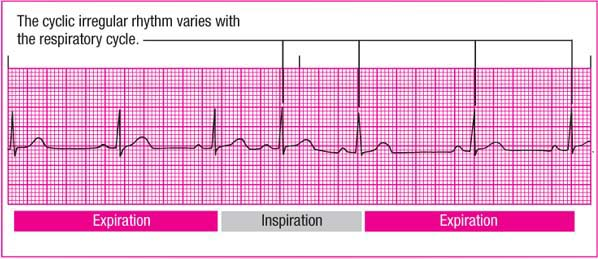

Sinus arrhythmia

In sinus tachycardia and sinus bradycardia, the cardiac rate falls outside the normal limits. In sinus arrhythmia, the rate stays within normal limits but the rhythm is irregular and corresponds to the respiratory cycle. Sinus arrhythmia can occur normally in athletes, children, and

older adults, but it rarely occurs in infants.

older adults, but it rarely occurs in infants.

Causes

Sinus arrhythmia, the heart’s normal response to respirations, results from an inhibition of reflex vagal activity, or tone. During inspiration, an increase in the flow of blood back to the heart reduces vagal tone, which increases the heart rate. ECG complexes fall closer together, which shortens the P-P interval. During expiration, venous return decreases, which in turn increases vagal tone, slows the heart rate, and lengthens the P-P interval. (See Recognizing sinus arrhythmia.)

Conditions unrelated to respiration may also produce sinus arrhythmia, including heart disease; inferior wall myocardial infarction (MI); the use of certain drugs, such as digoxin and morphine; and conditions involving increased intracranial pressure.

Clinical significance

ECG characteristics

Rhythm: Atrial rhythm is irregular, corresponding to the respiratory cycle. The P-P interval is shorter during inspiration, longer during expiration. The difference between the longest and shortest P-P interval exceeds 0.12 second. Ventricular rhythm is also irregular, corresponding to the respiratory cycle. The R-R interval is shorter during inspiration, longer during expiration. The difference between the longest and shortest R-R interval exceeds 0.12 second.

Rate: Atrial and ventricular rates are within normal limits (60 to 100 beats/minute) and vary with respiration. Typically, the heart rate increases during inspiration and decreases during expiration.

P wave: Normal size and configuration; P wave precedes each QRS complex.

PR interval: May vary slightly within normal limits.

QRS complex: Normal duration and configuration.

T wave: Normal size and configuration.

QT interval: May vary slightly, but usually within normal limits.

Other: None.

Signs and symptoms

The patient’s peripheral pulse rate increases during inspiration and decreases during expiration. Sinus arrhythmia is easier to detect when the heart rate is slow; it may disappear when the heart rate increases, as with exercise.

If the arrhythmia is caused by an underlying condition, you may note signs and symptoms of that condition. Marked sinus arrhythmia may cause dizziness or syncope in some cases.

Interventions

Unless the patient is symptomatic, treatment usually isn’t necessary. If sinus arrhythmia is unrelated to respirations, the underlying cause may require treatment.

When caring for a patient with sinus arrhythmia, observe the heart rhythm during respiration to determine whether the arrhythmia coincides with the respiratory cycle. Check the monitor carefully to avoid an inaccurate interpretation of the waveform.

If sinus arrhythmia is induced by medications, such as morphine and other sedatives, the practitioner may decide to continue to give the patient the medications because discontinuing them may be worse for the patient than the rhythm itself.

If sinus arrhythmia develops suddenly in a patient taking digoxin, notify the practitioner immediately. The patient may be experiencing digoxin toxicity.

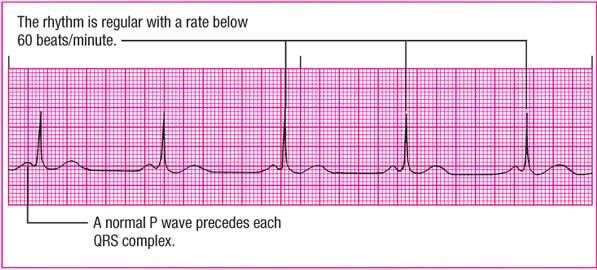

Sinus bradycardia

Sinus bradycardia is characterized by a sinus rate below 60 beats/minute and a regular rhythm. All impulses originate in the SA node. This arrhythmia’s significance depends on the symptoms and the underlying cause. Unless the patient shows symptoms of decreased cardiac output, no treatment is necessary. (See Recognizing sinus bradycardia and Bradycardia and tachycardia in children, page 100.)

Causes

Sinus bradycardia usually occurs as the normal response to a reduced demand for blood flow. In this case, vagal stimulation increases and sympathetic stimulation decreases. As a result, automaticity (the tendency of cells to initiate their own impulses) in the SA node diminishes. It may occur normally during sleep or in a person with a well-conditioned heart—an athlete, for example.

Sinus bradycardia may be caused by:

noncardiac disorders, such as hyperkalemia, increased intracranial pressure, hypothyroidism, hypothermia, and glaucoma

conditions producing excess vagal stimulation or decreased sympathetic stimulation, such as sleep, deep relaxation, Valsalva’s maneuver, carotid sinus massage, and vomiting

cardiac diseases, such as SA node disease, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, and myocardial ischemia, can also occur immediately following an inferior wall MI that involves the right coronary artery, which supplies blood to the SA node

certain drugs, especially beta-adrenergic blockers, digoxin, calcium channel blockers, lithium, and antiarrhythmics, such as sotalol (Betapace), amiodarone (Cordarone), propafenone (Rhythmol), and quinidine.

Clinical significance

The clinical significance of sinus bradycardia depends on how low the rate is and whether the patient is symptomatic. For example, most adults can tolerate a sinus bradycardia of 45 to 59 beats/minute but are less tolerant of a rate below 45 beats/minute.

Usually, sinus bradycardia doesn’t produce symptoms and is

insignificant. Many athletes develop sinus bradycardia because their well-conditioned hearts can maintain a normal stroke volume with less-than-normal effort. Sinus bradycardia also occurs normally during sleep as a result of circadian variations in heart rate.

insignificant. Many athletes develop sinus bradycardia because their well-conditioned hearts can maintain a normal stroke volume with less-than-normal effort. Sinus bradycardia also occurs normally during sleep as a result of circadian variations in heart rate.

When sinus bradycardia produces symptoms, however, prompt attention is critical. The heart of a patient with underlying cardiac disease may not be able to compensate for a drop in rate by increasing its stroke volume. The resulting drop in cardiac output produces such signs and symptoms as hypotension and dizziness. Bradycardia may also predispose some patients to more serious arrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation.

In a patient with acute inferior wall MI, sinus bradycardia is considered a favorable prognostic sign, unless it’s accompanied by hypotension. Because sinus bradycardia rarely affects children, it’s considered a poor prognostic sign in ill children.

ECG characteristics

Rhythm: Atrial and ventricular rhythms are regular.

Rate: Atrial and ventricular rates are less than 60 beats/minute.

P wave: Normal size and configuration; P wave precedes each QRS complex.

PR interval: Within normal limits and constant.

QRS complex: Normal duration and configuration.

T wave: Normal size and configuration.

QT interval: Within normal limits, but may be prolonged.

Other: None.

Bradycardia and tachycardia in children

Evaluate bradycardia and tachycardia in children in context. Bradycardia (less than 90 beats/ minute) may occur in the healthy infant during sleep, and tachycardia may occur when the child is crying or otherwise upset. Because the heart rate varies considerably from the neonate to the adolescent, neither bradycardia nor tachycardia can be assigned a single definition that can be used for all children.

Signs and symptoms

The patient will have a pulse rate of less than 60 beats/minute, with a regular rhythm. As long as he’s able to compensate for the decreased cardiac output, he’s likely to remain asymptomatic. If compensatory mechanisms fail, however, signs and symptoms of declining cardiac output usually appear, including:

hypotension

cool, clammy skin

altered mental status

dizziness

blurred vision

crackles, dyspnea, and third heart sound (S3), indicating heart failure

chest pain

syncope.

Palpitations and pulse irregularities may occur if the patient experiences ectopy such as premature atrial, junctional, or ventricular contractions. This is because the SA node’s increased relative refractory period permits ectopic firing. Bradycardia-induced syncope (Stokes-Adams attack) may also occur.