Sarcoidosis

Linda S. Efferen MD, FACP, FCCP

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disorder of unknown etiology that is characterized pathologically by the presence of nonnecrotizing granulomatous lesions. It generally affects young, previously healthy adults. Most patients present with typical clinical or radiographic features, but atypical presentations are well known and may mimic other diseases such as tuberculosis or malignancy.

Treatment is nonspecific. Corticosteroids can be used in an attempt to ameliorate significant symptoms and prevent progression of disease in vital organ systems. However, it is unclear if therapy alters the course or eventual outcome of disease (Fanburg & Lazarus, 1994).

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

Pathology

The granulomatous lesion in sarcoidosis is typical but nonspecific and is often found in multiple areas of the body, even in the absence of clinical disease. In the lung, activated T lymphocytes interact with alveolar macrophages infiltrating the air space and interstitium. Interactions among these cells, fibroblasts, and other cells in the lung dictate the course of disease. Alveolar macrophages may amplify inflammation and fibrogenesis by releasing various biochemical markers and cytokines or may suppress or downregulate the inflammatory response.

Resolution of the alveolitis or progression with development of granulomatous lesions may occur. Characteristic microscopic granulomas composed of tightly clustered epithelioid histiocytes may occur, often including multinucleated giant cells. The central core of the granuloma is surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells. Central necrosis is rare. The granulomatous lesions may resolve or progress to fibrosis and permanent scarring. These characteristic lesions are not specific for sarcoidosis, however, and can be seen in mycobacterial and fungal infections, berylliosis, extrinsic allergic alveolitis, malignancy, drugs, and foreign body reactions.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Sarcoidosis has a worldwide distribution, although the reported prevalence of disease varies widely—from 0.04 per 100,000 in Spain to 64 per 100,000 in Sweden. The disease appears to be rare in Africa and Central and South America. The reported rate from North America, Europe, Japan, and the United Kingdom is 10 to 20 per 100,000. In the United States, prevalence ranges from 11 to 71 per 100,000. This large variation may be due in part to variation in medical practice and the frequency with which routine chest radiographs are obtained in a specific region. Based on autopsy, it has been estimated that the true incidence of sarcoidosis may be 10-fold higher than clinical estimates.

Race and gender affect the incidence of disease. African American women experience the highest risk for developing sarcoidosis. In the United States, women are affected more frequently than men, and the prevalence of sarcoidosis among African Americans has been reported to be 8 to 10 times greater than in whites.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is often suggested by the clinical or radiographic presentation. Sarcoidosis is a disease of young, previously healthy adults; approximately 80% of patients are ages 20 to 40 on initial presentation. Although sarcoidosis can affect any organ system, approximately 90% of patients exhibit signs or symptoms of the disease referable to the chest. When typical clinical and radiographic features are present in a young, previously healthy person, it is highly suggestive of sarcoidosis.

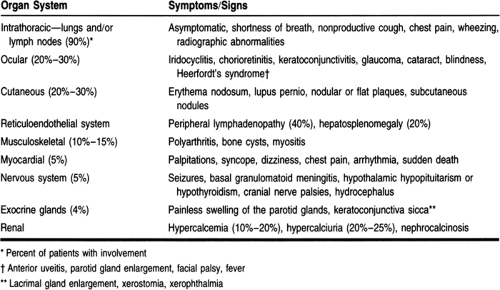

Patients may be asymptomatic on presentation, with characteristic abnormalities found on routine chest radiographs. Symptomatic patients frequently present with an insidious onset of symptoms or findings from pulmonary, ocular, or cutaneous lesions (Table 78-1). Symptoms of fatigue, weakness, malaise, fever, and loss of weight are seen in 40% to 50% of cases. Occasionally patients present with an acute onset of symptoms, including fever, polyarthritis, iritis, and erythema nodosum, suggesting Lofgren’s syndrome.

Routine laboratory tests may reveal abnormalities suggestive of sarcoidosis. Hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, and elevated liver enzymes, especially alkaline phosphatase, may be present. Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia is variably reported in 25% to 80% of patients, and leukopenia occurs in 5% to 10%.

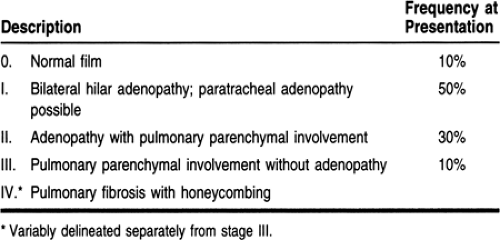

The chest radiograph may reveal bilateral hilar or mediastinal adenopathy with or without pulmonary parenchymal involvement. Pulmonary fibrosis and honeycombing may be seen, although a normal chest radiograph is also possible (Table 78-2).

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis requires the exclusion of other diseases that can present with similar clinical, radiographic, and pathologic features. A demonstration of nonnecrotizing granulomatous lesions in pathologic specimens, in an appropriate clinical setting and in the absence of evidence supporting alternative etiologies, would be considered diagnostic. At times, the clinical presentation may be sufficiently typical to preclude the need for tissue confirmation, particularly in an asymptomatic person.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

Most patients with sarcoidosis are asymptomatic. In symptomatic ones, a subacute or chronic presentation is most often found. The pulmonary system is the most common organ system involved, and symptoms include cough, shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and chest pain. An acute onset of symptoms and physical findings is seen in 10% to 15% of cases.

Findings on the physical exam depend on the organ system involved. The chest exam is usually normal, although end-inspiratory crackles or wheezing may be present. Ocular and cutaneous manifestations of the disease are frequent and fairly characteristic. Unusual signs or symptoms from commonly affected organ systems or from less frequently involved systems may lead to an initial delay in considering the diagnosis.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

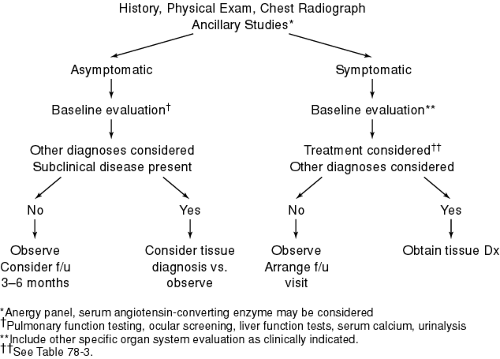

An initial evaluation including pulmonary function tests, ocular screening, liver function tests, and serum calcium levels should be performed to evaluate the presence of occult, multiorgan system disease and to serve as a baseline for subsequent evaluation and testing (Fig. 78-1). In symptomatic patients, evaluation specific to the organ system involved should also be included. Tuberculin skin testing is usually performed and often demonstrates cutaneous anergy.

The most frequent abnormality detected on pulmonary function testing is a restrictive lung pattern characterized by decreased lung volumes and diffusing capacity. Reduced expiratory air flow rates, indicative of airflow obstruction, occur in approximately 20% of cases. Airway hyperreactivity to methacholine

challenge is demonstrable in a smaller percentage of patients. In general, pulmonary function testing is not a reliable means for detecting disease or estimating the extent of disease and does not correlate with clinical or radiographic findings. However, sequential measurements may allow assessment of change in individual patients.

challenge is demonstrable in a smaller percentage of patients. In general, pulmonary function testing is not a reliable means for detecting disease or estimating the extent of disease and does not correlate with clinical or radiographic findings. However, sequential measurements may allow assessment of change in individual patients.

The need for tissue diagnosis should be determined clinically. In an asymptomatic patient with characteristic radiographic findings in whom treatment is not being considered, tissue diagnosis may be unnecessary unless an alternative diagnosis such as tuberculosis or lymphoma is clinically suspected. When tissue diagnosis is required, fiberoptic bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsies is the method most frequently used. It is diagnostic in 75% to 90% of patients with abnormal chest radiographs (stage I to III) and in up to 50% of patients with a normal radiograph (stage 0).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree