Renal Tumors

B. Mayer Grob MD

Benign and malignant renal tumors are often diagnosed in the workup of hematuria. In addition, incidental renal masses are frequently seen in the evaluation of nonurologic abnormalities on sonograms, computed tomography (CT) scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The primary care provider should be acquainted with the appropriate evaluation and treatment of the common renal neoplasms. Working together with the urologist, these problems can usually be managed successfully.

OVERVIEW OF RENAL TUMORS

Diagnostic Criteria

Although the number of renal masses detected incidentally is increasing, many are still found in the workup of hematuria. The definition of hematuria is not completely clear. Excretion rates of red blood cells (RBC) for normal persons is 500,000 to 1 million per 12 hours. The semiquantitative method of counting the number of cells per high-power field of urine sediment has been shown to correlate well with the 12-hour excretion rates. Ninety percent of normal persons have less than 1 RBC per high-power field, and 97% have less than 5 RBCs per high-power field of urine sediment (Larcom, 1948). There is no universally accepted standard amount of microscopic hematuria that should prompt a full evaluation. Some providers believe that 1 RBC per high-power field is abnormal enough to initiate a workup, but almost all would agree that a urinalysis showing more than 5 RBCs should be evaluated further. Hematuria in the presence of significant proteinuria, however, is often attributable to glomerular disease, and a urologic evaluation is not usually necessary. It may be more reasonable to refer the patient to a nephrologist.

History and Physical Exam

A complete history and physical exam are part of any hematuria workup. The precise nature of the hematuria should be elucidated. Hematuria accompanied by pain, either in the flank or the pelvis, may be an indication of stone disease. Pain from stone disease is often colicky and of sudden onset compared to pain from a slowly growing mass. Fever may be an indication of an infection, possibly pyelonephritis. Pyuria is significant in almost all cases, and hematuria, without pyuria, should not be attributed to infection. The passage of blood clots can sometimes help to localize the site of bleeding to the upper tracts—long and string-like versus more clumped (bladder). Recent trauma may be readily apparent in some patients, but hematuria secondary to apparently trivial trauma may indicate a condition such as a ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Recent strenuous physical exercise is sometimes associated with hematuria as well. A past history of urologic conditions or procedures is obviously important. A family history of urologic disease may be crucial because some cases of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) are familial, with and without von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. Occupational exposures to the rubber and dye industry are particularly relevant to transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), and a social history, including cigarette use, is important.

A thorough exam of the flank, abdomen, and genitalia should be included in the physical. Any unusual mass should be carefully characterized. Adenopathy is an ominous sign.

Diagnostic Studies

Urinary exfoliative cytology is also important in the workup of hematuria. TCC, whether of the bladder or upper urinary tract, has a loosely coherent outer layer. These are the cells that are often identified on a urinary cytology. Bladder cancers are much more common than renal tumors. Although a negative result on cytology does not rule out bladder cancer, a positive cytology result often helps direct the course of therapy. In addition, because some renal TCCs are difficult to distinguish from RCC, a positive cytology result can shift the treatment plan for renal tumors; as will be described later, the surgical approach for renal TCC is different from that for RCC.

Two new urine tests have recently become available in the evaluation of hematuria. The Bard BTA-stat (bladder tumor-associated analyte) and the Matritech NMP22 (nuclear matrix protein) (Sarosdy, 1995; Soloway, 1996) urine tests identify unique markers in the urine of patients with bladder cancer. Although their role has not clearly been defined, these tests may be particularly helpful in following patients with bladder cancer. They are mentioned here for completeness in the diagnostic criteria for hematuria. Whether either will play a role in the evaluation of upper tract TCC is not known at the time of this writing.

Intravenous urography (IVU) remains the initial imaging study of choice for most patients in the workup of hematuria. Ultrasonography (US) is an excellent test to differentiate solid from cystic lesions of the kidney; however, US alone is not sensitive enough to identify most urothelial tumors, specifically TCC of the renal pelvis or ureter. Masses seen on US that meet the strict criteria for a simple cyst need no further evaluation. These criteria include a fluid-filled mass with a distinct posterior wall and acoustic enhancement, without calcification, septation, or nodularity. In some cases, US may not confirm the existence of a mass seen initially on IVU; a CT scan should then be obtained with and without contrast to take advantage of the vascular nature of most RCCs. In patients allergic to

contrast media and unwilling to accept intravenous contrast after steroid preparation, and in patients with marginal renal function, an MRI with gadolinium is also an excellent test in the evaluation of renal masses. Renal angiography is seldom necessary today, although in the past it was often used to clarify an abnormal IVU. Angiography is sometimes helpful in preparation for a partial nephrectomy, especially in a patient with a solitary kidney or multiple renal masses.

contrast media and unwilling to accept intravenous contrast after steroid preparation, and in patients with marginal renal function, an MRI with gadolinium is also an excellent test in the evaluation of renal masses. Renal angiography is seldom necessary today, although in the past it was often used to clarify an abnormal IVU. Angiography is sometimes helpful in preparation for a partial nephrectomy, especially in a patient with a solitary kidney or multiple renal masses.

Imaging studies provide information about the kidneys and ureters but cannot adequately assess the bladder. Large bladder tumors are sometimes seen on an IVU or CT scan, but smaller tumors and carcinoma in situ are not reliably detected on any imaging test. Cystoscopy is necessary to complete the hematuria workup. This can often be performed in the urologist’s office or an ambulatory surgery center. If the result of the urine cytology is positive, or if an abnormality is detected on upper tract imaging studies, the cystoscopy may be performed with anesthesia. This allows samples to be taken for bladder biopsy or ureteropyelography to be accomplished without patient discomfort.

SPECIFIC RENAL TUMORS

Benign Renal Neoplasms

RENAL ADENOMA

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

The classification “renal adenoma” is controversial. It may be possible to distinguish an RCC from a renal adenoma based on nuclear and cytoplasmic criteria, but there are no reliable gross, microscopic, or ultrastructural differences between the two lesions. Previously, size alone was the standard criteria. This was based on the autopsy study by Bell (1950), demonstrating that renal lesions smaller than 3 cm rarely metastasized, whereas almost 70% of lesions greater than 3 cm had metastasized. There are, however, several reports of lesions as small as 5 mm with metastases. Small, solid renal masses that enhance with intravenous contrast are probably small RCCs.

One recent study of several thousand autopsy and surgical specimens described two distinct histologic types of adenomas (Faria, 1994). Adenomas with a papillary or tubulopapillary pattern are more common, are smaller, are frequently multiple, and probably are not precursors of RCC. They are usually composed of basophilic or oncocytic cells. Adenomas with a solid or papillary pattern are frequently solitary, are larger, and may be a morphologic precursor of RCC. They are often composed of clear cells.

Epidemiology

In autopsy series, renal adenomas have been found in about 20% of cases (Bonsib, 1985). In large screening ultrasound series, however, the clinical detection rate is much less than 1%. The male/female ratio is 3:1. Certain diseases have a significantly higher incidence of adenomas. Patients with VHL disease have a tendency to develop renal cysts and solid renal tumors. Some of these may be adenomas, but there is an association with potentially lethal RCC as well. Patients with acquired renal cystic disease on dialysis for end-stage renal disease are also prone to develop small but potentially metastatic renal tumors. These have historically been labeled adenomas but are probably small RCCs.

Treatment Options, Expected Outcomes, and Comprehensive Management

Most small adenomas are asymptomatic. They are detected incidentally on CT or US during the workup for an unrelated medical problem. Rarely, they can present as a source of bleeding. Even larger adenomas are usually discovered incidentally, but they are more likely to present with symptoms referable to the urinary tract. Flank pain and hematuria have been associated with larger adenomas.

Renal adenomas appear as solid masses on IVU. They cannot be distinguished from RCC by imaging techniques, and most urologists think these tumors should be treated as if they were RCCs. How should these small RCCs or renal adenomas be managed? Although the standard therapeutic approach for RCC remains radical nephrectomy, there is growing interest in the use of partial nephrectomy, especially for incidentally discovered lesions. In select cases, it may even be reasonable to observe small tumors. A recent report by Bosniak et al (1995) showed that for lesions less than 3 cm at diagnosis, and followed for at least 2 years, no metastases were clinically detectable. The majority of patients eventually went on to have surgery, and none developed metastases. This “watchful waiting” approach may be acceptable for an elderly patient with other significant medical problems, but it should be undertaken in consultation with a urologist. It is certainly not to be suggested in the young and otherwise healthy patient, because small renal tumors do grow and do have the capacity to metastasize.

RENAL ONCOCYTOMA

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

Grossly, oncocytomas are well-circumscribed tumors with a characteristic mahogany color. A large stellate central scar is often seen. Hemorrhage and necrosis are typically absent. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of large well-differentiated cells with intensely eosinophilic cytoplasm. These oncocytes rarely exhibit mitoses.

Epidemiology

Oncocytomas account for 3% to 14% of all renal tumors. The male/female ratio is 2:1. They are usually solitary, and the peak age of incidence is 55 years. They are occasionally found in the same kidney with RCC, on rare occasions within the same lesion.

Treatment Options, Expected Outcomes, and Comprehensive Management

Approximately 70% of oncocytomas are detected incidentally. The remainder present with complaints referable to the genitourinary system. Hematuria, flank pain, and a flank mass are the typical symptoms. Oncocytomas appear as solid masses on IVU or US. They cannot be distinguished from RCC on radiologic grounds. A central scar seen on CT or a “spoke-wheel” appearance on angiography may suggest an oncocytoma, but there is simply no reliable method to rule out RCC preoperatively.

Pure oncocytomas are benign lesions. However, because there is no reliable clinical method to differentiate oncocytomas from RCCs, they are usually treated as RCCs and managed with nephrectomy. As is the case for renal adenomas, small incidentally discovered lesions suggestive of oncocytoma may be treated successfully with a partial nephrectomy. This scenario is not an indication for a percutaneous renal biopsy. Because

of the occasional occurrence of oncocytoma and RCC in the same lesion, and because some RCCs have oncocytic features, the diagnosis of oncocytoma cannot be made with a small sampling of tissue.

of the occasional occurrence of oncocytoma and RCC in the same lesion, and because some RCCs have oncocytic features, the diagnosis of oncocytoma cannot be made with a small sampling of tissue.

ANGIOMYOLIPOMA

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

The gross appearance is determined by the relative amounts of the various cellular components. If the lesion is composed predominantly of fat, it will have a homogeneous yellowish appearance, but all three cell types must be present to establish the diagnosis. The lesion will be more heterogeneous if there is an even distribution of fat, muscle, and vessels. Calcification and necrosis are rare, but hemorrhage is frequent.

Epidemiology

Hamartomas are neoplastic masses of disorganized cells or tissue normally seen in a particular organ. The most familiar renal hamartoma is the angiomyolipoma, named for the three components observed in this lesion: blood vessels, smooth muscle, and fat. These tumors are particularly interesting because they are the only benign renal masses that can be reliably diagnosed radiographically.

Angiomyolipomas are seen in two distinct clinical settings: sporadic and in association with tuberous sclerosis. The sporadic form accounts for more than 80% of cases. It is more common in women, with a ratio of 4:1, and the mean age is 43 years. Tuberous sclerosis is a congenital and familial disorder characterized by brain gliosis, mental retardation, epilepsy, adenoma sebaceum, and hamartomas of the retina, lungs, liver, pancreas, bone, and kidneys. Angiomyolipomas associated with tuberous sclerosis present as larger lesions, at a younger age, and are more likely to be symptomatic and require surgical intervention.

Treatment Options, Expected Outcome, and Comprehensive Management

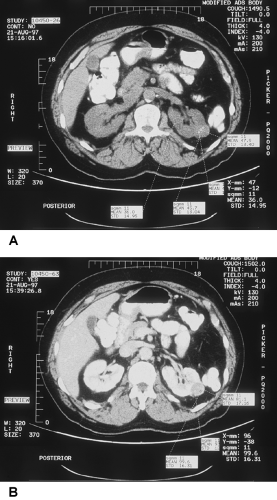

Plain radiographs occasionally show lucent areas within large angiomyolipomas, suggesting the diagnosis, but typically the IVU demonstrates an expansile mass that cannot be distinguished from RCC. On US, they are usually more echogenic than surrounding parenchyma. They share this feature with about one third of RCCs, however. With the development of high-quality CT scanning, it was realized that the detection of fat within a renal lesion allows confident preoperative diagnosis and the potential to avoid surgery in most cases that are not symptomatic (Fig. 33-1).

The most common presentation is incidental discovery during imaging for other medical conditions. Patients may present with acute flank pain with or without spontaneous hemorrhage. Occasionally, the onset of symptoms is preceded by seemingly trivial trauma. The blood vessels of angiomyolipoma lack a complete elastic layer, predisposing these lesions to aneurysm formation and bleeding. Steiner et al demonstrated that lesions less than 4 cm rarely become symptomatic, whereas lesions greater than 4 cm require surgical intervention in about half the cases for bleeding (Steiner, 1993).

When the CT scan is unequivocal and the patient is asymptomatic, no intervention is required for small angiomyolipomas. In cases where the diagnosis is in question, exploration and partial or radical nephrectomy may be necessary. Symptomatic patients with angiomyolipomas can often be treated successfully with percutaneous angioinfarction (Table 33-1).

Malignant Renal Neoplasms

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree