Prostatic Disease

Matthew R. Anderson MD

Three diagnoses—benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), prostate cancer, and prostatitis—represent the core of prostatic disease in primary care. BPH and prostate cancer have assumed increasing importance as the population of North America ages. Prostate cancer is now the most commonly diagnosed noncutaneous tumor and the second leading cause of cancer death in men (American Cancer Society [ACS], 1997).

The field of prostate disease is mired in controversy. It is unclear whether screening for prostate cancer is beneficial; recommendations by professional bodies have been widely divergent. Disagreement exists over which treatment is best for localized prostate cancer. The answers to these questions should become clearer in the next decade. Until then, primary care providers and their patients will have to make difficult decisions based on inadequate data.

Despite these ambiguities, the primary care provider plays a key role in the management of prostatic diseases, even though much of prostate-related care is handled by specialists. Patients come to their primary care provider first with their concerns, symptoms, or anxieties. Despite referral to a specialist, the primary care provider retains an important responsibility to counsel patients and verify that they are receiving accurate advice. In caring for men throughout their life cycle, the primary care provider offers them support in coping with their symptoms, the morbidities of interventions (eg, erectile dysfunction and incontinence), and the realities of a much-feared terminal illness.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The base of the prostate lies superiorly against the bladder; the apex lies below, against the urogenital diaphragm. The anterior aspect of the prostate lies against the symphysis pubis, whereas the posterior aspect sits in front of the rectum. Only the posterior aspect of the prostate is palpable.

The prostate contains multiple epithelial glands that produce a thin, milky secretion. This secretion drains via approximately 25 ducts into the back of the urethra. Smooth muscle in both the prostatic capsule and stroma contracts during ejaculation, expelling the secretion into the ejaculate. The prostatic secretion is alkaline, in contrast to the other components of the ejaculate and to the vaginal pH, both of which are acidic. Because sperm are optimally motile at a higher (ie, more alkaline) pH, the prostatic secretion may play a role in maintaining a suitable pH for sperm.

Understanding of the pathophysiology and natural history of prostate conditions is still fragmentary. The relation between the clinical entity of “prostatism” and the prostate gland is obscure. The cause of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis, the most common type of prostatitis, is not clearly known. How to distinguish the prostate cancers that are aggressive from those that are indolent remains a mystery.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA AND HISTORY

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

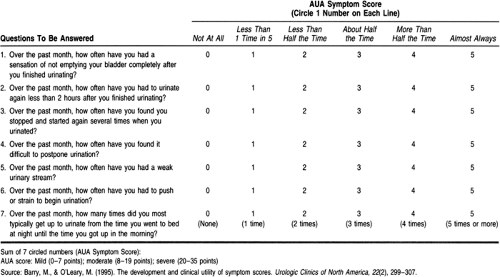

Tradition has divided symptoms of “prostatism” into those of obstruction (hesitancy, poor flow, intermittency, abdominal straining, feeling of not fully emptying bladder, dribbling, and double voiding) and those of irritation (dysuria, nocturia, urgency or urge incontinence, and frequency). A seven-question symptom index was developed by the American Urological Association (AUA) to evaluate the response to therapies for BPH (Table 68-1). The index is used in some settings for making clinical decisions (Barry & O’Leary, 1995).

More recent research has cast doubt on the relation between “prostatism” and the prostate gland. Urodynamic studies and transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) have demonstrated that the AUA symptoms are neither sensitive nor specific for prostatic obstruction. The AUA symptom index is not even statistically related to a number of anatomic and physiologic variables, such as the peak urinary flow rate or the postvoid residual, which are thought to be associated with urinary obstruction. A study of unselected adults age 55 to 79 found no significant differences between AUA symptom scores in men and women (Lepor & Machi, 1993). It would probably be more appropriate to consider these as symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction rather than prostate disease. The differential diagnosis for such dysfunction includes cystitis, bladder cancer, ureteral stricture, bladder diverticulae, neurogenic bladder, bladder neck dyssynergia, ureteral stricture, and bladder calculi.

Symptoms of prostatism also need to be evaluated with a sense of how bothersome they are for the patient. Many men find their voiding symptoms tolerable and would prefer not to undergo treatment that has important potential morbidities.

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is often asymptomatic until well advanced. It can cause erectile dysfunction or symptoms of obstruction. More commonly, it presents with metastatic disease. Bony pain is typical in metastatic disease; the pain location depends on the area of tumor spread. Frank spinal cord compression or other neurologic compromise also can occur (Palmer & Chodak, 1996).

Prostatitis

Prostatitis presents with a broad array of symptoms. These may include the classic symptoms of prostatism or symptoms of dyspareunia (painful ejaculation). The patient with bacterial prostatitis

may present with fever and septic shock. Prostatodynia refers to a poorly understood symptom complex of pain that can be experienced in the perineal or rectal area or lower back. The prostate gland itself may not be the cause of prostatodynia.

may present with fever and septic shock. Prostatodynia refers to a poorly understood symptom complex of pain that can be experienced in the perineal or rectal area or lower back. The prostate gland itself may not be the cause of prostatodynia.

Hematospermia (bloody ejaculate) generally reflects disease of either the prostate or seminal vesicles. Hematuria may suggest prostatic disease but can arise from anywhere in the genitourinary tract. Incontinence is not generally a result of purely prostatic disease.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

The prostate examination (digital rectal examination [DRE]) tends to be uncomfortable for the patient, but it can provide important diagnostic information. Its value as a screening test is controversial.

CLINICAL WARNING

Perform DRE very gently in a patient with acute bacterial prostatitis.

As the palpating finger moves superiorly above the anorectal junction, the prostate is felt as a walnut-sized mass.

CLINICAL PEARLS

Before beginning the exam, inform the patient that it is normal to feel a desire to urinate as the prostate is palpated.

The median sulcus is easily palpated, as are two lateral lobes. The seminal vesicles lie superior to the prostate and are not normally palpable.

The examiner can palpate only the posterior surface of the prostate; any anterior lesion will escape detection. This is an important limitation of the DRE.

Several characteristics of the prostate examination have diagnostic importance:

Consistency: The various consistencies of the prostate gland can be illustrated on the hand (Sapira, 1990). The normal consistency of the prostate gland is that of the thenar eminence when contracted—for example, when the thumb is opposed to the little finger. When the muscle is relaxed, it gives the boggy feel of a benign enlarged prostate. Hard nodules are like the bony prominences of the hand; indurated areas are like those of the taut extensor pollices.

Symmetry: Asymmetry of the prostate can indicate carcinoma.

Nodularity: In general, inflammatory nodules are raised; cancerous ones are not. A prostate cancer is often obvious as a hard mass. This mass may extend beyond the capsule of the prostate and fix the organ to the pelvic wall.

Size: The normal size of a prostate is best learned with practice. It is described as being the size of a plum, a golf ball, or a walnut. Urologists often estimate the size in grams. A normal-sized prostate is said to be 20 g, a lemon-sized prostate 35 g, and a baseball-sized prostate 60 g.

CLINICAL PEARL

The size of the prostate on palpation does not correlate with the degree of urethral obstruction. Estimation of prostate size is not particularly useful diagnostically. However, prostate size may influence the choice of therapy for BPH.

Prostatic Massage

Prostatic massage is done to evaluate patients with symptoms of chronic prostatitis. Prostatic massage is not done in acute prostatitis for fear of precipitating bacteremia. Prostatic massage is done either alone or as part of a three-glass test (also known as the four-glass test). This test is described below. Expressed prostatic secretions (EPS) should be cultured for bacteria and mycobacteria. Additional cultures for gonococci and parasites may be appropriate in certain settings.

Prostatic massage is best accomplished by rolling rather than pushing the finger, as this is gentler on the rectum. The basic motion is that of massaging toward the midline of the prostate and down. An occasional patient will have no secretions at the tip of his penis after massage; these patients can be instructed to milk the penis. If no secretions are obtained at this point, the patient should void a few drops of urine, which will contain liquid from the prostate.

Normal prostatic secretions contain lecithin bodies and epithelial cells. The presence of many white cells is diagnostic for prostatitis. Experts disagree on the exact number, but 10 white cells per high-power field is generally accepted as evidence of prostatitis. The presence of fat-laden macrophages is specific for prostatic inflammation (Tanagho & McAninch, 1995).

Estimation of Bladder Size

In patients with prostatic obstruction, it is important to evaluate for possible urinary retention, either acute or chronic. Patients with chronic retention can have massively enlarged bladders and still be relatively or entirely asymptomatic.

Approximately 400 cc of urine must be present in the bladder before it can be palpated suprapubically. A more sensitive method is percussion.

CLINICAL PEARLS

The presence of a dull percussive note one fingerbreadth above the symphysis is a reliable sign that there is at least 100 cc of urine in the bladder (Boyarsky & Goldenberg, 1962).

An alternate technique uses auscultatory percussion (Guarino, 1985). The diaphragm of the stethoscope is placed just above the symphysis and the finger percusses caudally from the subcostal area. The point at which the auscultatory note changes is a reliable indicator of bladder height. An estimated height 1 cm above the stethoscope’s diaphragm corresponds to a bladder volume of approximately 100 cc. Experience and confidence with these techniques can be gained if they are practiced before assessing a postvoid residual.

Postvoid Residual

If there is doubt concerning the size of the bladder, a postvoid residual can be obtained with a Foley catheter or by using ultrasound. Ultrasound is obviously less traumatic for the patient but may not be available in all clinics. In general, postvoid values of more than 50 to 100 cc of urine are considered evidence of retention.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Evaluation of Urine and Prostatic Secretions

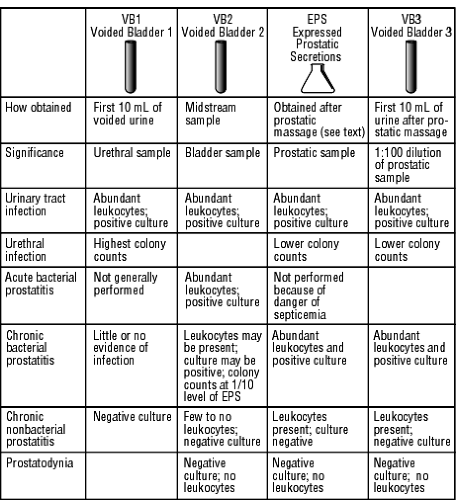

A basic urinalysis and urine culture should be performed in all patients with prostatic symptoms. EPS are generally cultured as part of the three- or four-glass test (Doble, 1994). Patients collect two urine samples before prostatic massage but should not fully empty the bladder at this time. The first two samples are labeled voided bladder 1 (VB1, the first 10 cc of urine voided) and VB2 (a midstream sample). After prostatic massage, an additional two samples are collected: the EPS and VB3 (the first 10 cc of urine voided after the EPS). VB1 is considered a urethral sample, VB2 is a sample of bladder contents, and VB3 is a 1:100 dilution of prostatic secretions. Figure 68-1 describes this test and its significance.

Three general patterns emerge in the three-glass test:

Bladder infections cause all four samples to show evidence of bacterial infection.

Urethral infection causes higher colony counts in the VB1 sample than in the EPS or VB3 sample.

Prostatitis causes the opposite pattern, ie, higher colony counts in EPS and VB3 than VB1 or VB2.

Serum Chemistries

The serum creatinine is used to evaluate kidney function. Acid and alkaline phosphatase played important roles historically in the management of prostate cancer, but these tests have been supplanted by PSA in current practice.

Prostate-Specific Antigen

PSA is a protease that functions to liquefy the ejaculate. It is produced throughout the prostate gland and, for practical purposes, is found nowhere else in the body. As the prostate

hypertrophies with age, more PSA is produced. PSA levels tend to increase with age, so the normal range increases as men grow older. Levels also increase in prostatitis and when the prostate is manipulated surgically or by cystoscopy.

hypertrophies with age, more PSA is produced. PSA levels tend to increase with age, so the normal range increases as men grow older. Levels also increase in prostatitis and when the prostate is manipulated surgically or by cystoscopy.

Difficulty arises in distinguishing PSA elevations from BPH and those from prostate cancer. This generally occurs with PSA levels in the range of 4 to 10 ng/mL.

CLINICAL WARNING

PSA levels above 10 ng/mL are more specific for cancer.

Four approaches have been proposed for discriminating borderline PSA values (4 to 10 ng/mL) in BPH versus prostate cancer, but none has gained complete acceptance. The approaches are:

PSA density: determined by dividing the PSA level by the weight of the prostate as determined by TRUS. This theoretically removes the increase in PSA secondary to hypertrophy.

PSA velocity: the PSA is plotted over time. PSA levels are expected to increase with age, but a change in the velocity of the increase is thought to signal malignant prostatic disease.

Age-specific PSA values have been published and are used by some laboratories (Oesterling et al, 1993).

Different molecular forms of PSA may be associated with different types of prostate disease.

CLINICAL PEARL

Finasteride, which is used in the treatment of BPH, decreases PSA values by about half (Gormley et al, 1992).

Urodynamic Studies

Urodynamics includes a variety of techniques, ranging from the simple to the sophisticated. Uroflowmetry is a simple test commonly used for evaluating symptoms of urinary obstruction. It is the urologic equivalent of the pulmonary flow-volume curve. The patient urinates into a special measuring device that produces a curve of flow versus time. The curve permits normal outflow to be distinguished from the decreased pattern characteristic of prostatic obstruction and the plateau characteristic of bladder neck obstruction. Unfortunately, there are limitations to uroflowmetry. Decreased flow can be caused by a lazy detrusor without prostatic obstruction. Normal flow can occur despite obstruction if the detrusor is hypertrophied. Maximum rates of less than 10 mL/second are highly suggestive of obstruction, whereas rates greater than 15 mL/second pretty much rule it out.

Transrectal Ultrasound

TRUS and transrectal biopsy are the current standards for evaluation of a suspicious finding on DRE or PSA. Some experts advocate TRUS as a screening test for prostate cancer. Cancers are usually hypoechoic on TRUS. However, most hypoechoic areas are not cancerous, so all abnormal areas must be biopsied. When no suspicious areas are found, some urologists perform multiple blind biopsies; others prefer to follow serial PSA levels. Bleeding is the main complication of prostatic biopsy.

BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA

The pathogenesis and management of BPH appear straightforward at first glance. As men age, their prostates show areas of hyperplasia or growth of new prostate cells. By the ninth decade, the prevalence of pathologic BPH can reach 90% (Berry et al, 1984). Hyperplasia leads to hypertrophy of the gland, with increases in size and weight. This process results in mechanical obstruction of the urethra as it passes through the prostate. Chronic obstruction leads to dysfunction of the bladder detrusor muscle. The resultant symptoms of “prostatism” can be detected and quantified by symptom scores such as those of the AUA index (Barry & O’Leary, 1995), presented in Table 68-1. These symptom scores can be used to guide management decisions.

Although this sequence of events may occur in some patients, nearly every element in this logical chain is suspect (Abrams, 1995). If hyperplasia is a common finding in elderly men, it might be better thought of as a normal part of aging. Hyperplasia is a microscopic diagnosis and does not necessarily equate with gland hypertrophy, a diagnosis based on TRUS or the physical exam. Hypertrophy of the gland does not necessarily imply obstruction, which is a diagnosis established by urodynamics. To complicate matters further, there appears to be little relation between urodynamically diagnosed obstruction and “obstructive” symptoms (Abrams et al, 1993). Finally, patients who are symptomatic may or may not need or want interventions that carry significant morbidities of their own.

Thus, the provider is left with the difficult task of understanding how a variety of medical diagnoses such as cellular hyperplasia, glandular hypertrophy, and urodynamic obstruction relate to the patient’s symptoms. The provider must help the patient decide which, if any, treatments are appropriate for his symptoms (Cassel, 1992).

Epidemiology

Despite the frequency of BPH and the quantity of resources invested in BPH treatment, the epidemiology of the condition remains poorly studied (Guess, 1995). The main risk factors are age and the presence of androgens.

How common BPH is depends on how it is defined: histologically, anatomically, urodynamically, or clinically. Natural history studies have been flawed but have reported that symptoms improve or stabilize in 42% to 86% of untreated patients (Oesterling, 1993). It has been estimated that 31% to 55% of men with BPH will have improvement of symptoms with watchful waiting (Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Guideline Panel, 1994).

Diagnostic Criteria

Whether volunteered by the patient or elicited by the primary care provider, voiding symptoms usually initiate the workup for BPH. Occasionally, the provider will notice an enlarged bladder that is entirely asymptomatic; this is known as silent

prostatism. The AUA symptom index presented in Table 68-1 may be useful at this point to establish a baseline of symptoms against which to judge the effects of therapy.

prostatism. The AUA symptom index presented in Table 68-1 may be useful at this point to establish a baseline of symptoms against which to judge the effects of therapy.

CLINICAL WARNING

High symptom scores are not diagnostic of prostatic obstruction. However, it may not be strictly necessary to prove that obstruction is the cause of the patient’s symptoms before proceeding with therapy.

The size of the prostate on physical exam is of little use diagnostically. Obstruction can occur with small prostates; conversely, large prostates do not necessarily obstruct. Evaluation of bladder size is diagnostically useful. When there is concern about bladder size, postvoid residual should be measured.

The minimum initial evaluation should include a urinalysis and creatinine measurement. These are done primarily to exclude other conditions, including infection or renal damage, rather than to confirm the diagnosis. Whether urodynamics and a PSA are necessary at this stage is controversial. Some providers order these tests routinely, but others do not.

Treatment Options, Expected Outcomes, and Comprehensive Management

Patients who do not meet the criteria for urologic referral can be managed in one of several ways. The choice is largely dictated by patient preference.

WATCHFUL WAITING

Many patients with symptoms of prostatism will improve over a 3- to 6-month waiting period. A frequency–volume chart may teach them to adjust their fluid intake and its timing (Kadow et al, 1988). This is discussed below. Pelvic floor and bladder exercises (Kegel exercises) and control of caffeine and alcohol intake may all be helpful in this setting. Kegel exercises are described in Chapter 34.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree