Plantar Fasciitis

Maria Procopio Dugan DO

Plantar heel pain is one of the most common orthopedic pain syndromes seen in a primary care practice. The true prevalence is not known. It affects both male and female patients of all ages but usually occurs in middle-aged to elderly patients or athletes. There are a multitude of potential causes of the painful heel syndrome (also known as heel spur syndrome and subcalcaneal pain), which can lead to some diagnostic uncertainty.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

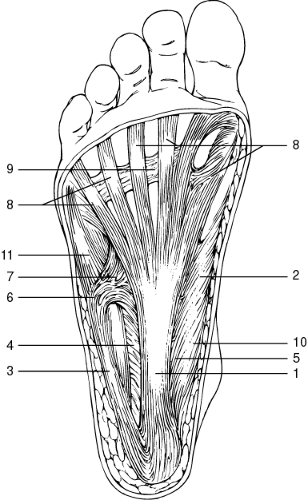

The plantar fascia, or aponeurosis, is a fibrous band of connective tissue in the sole that extends proximally from the medial calcaneal tuberosity to the metatarsal heads. The central portion, which originates from the medial calcaneus, is the thickest and narrowest, with fibers arranged longitudinally. The thinner and smaller lateral and medial portions cover the abductor digiti minimi and abductor hallucis muscles. Distally, the fascia widens and thins, dividing into five rays that attach to each toe (Fig. 49-1).

The plantar fascia provides stability to the arch of the foot and functions through a windlass-type mechanism to depress the metatarsal heads and raise the longitudinal arch (Hicks, 1954). This occurs when the toes are dorsiflexed, passively pulling the fascia under the metatarsal heads, which causes the fascia to tighten, thereby shortening the distance between the heel and the forefoot and increasing the height of the arch. The work of raising the arch is done by body weight; no muscle is directly involved in the mechanism. Through the windlass effect, the plantar fascia and the bony and ligamentous support of the foot maintain the arch during weight bearing. During normal gait, the foot pronates at heel strike to become flexible enough to conform to the ground and partially absorb the initial contact force (Karr, 1994). At toe-off, the plantar fascia becomes taut, which aids in the resupination of the foot.

Inflammation and microtears of the plantar fascia near its origin from the medial calcaneal tubercle appear to be the pathologic process responsible for pain. If left untreated, or if trauma is permitted to continue, the inflammatory response will progress and thickening, fibrosis, chronic granulomatous tissue, or mucinoid degeneration of the plantar fascia will ensue (Furey, 1975; Davis et al, 1994; Schepsis et al, 1991).

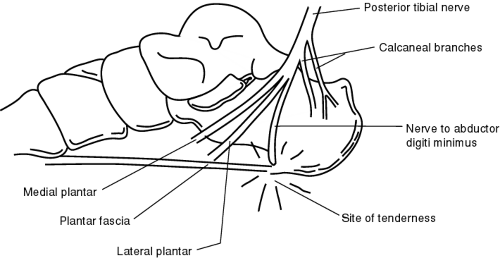

Entrapment of the medial calcaneal nerves, the lateral plantar nerve, or the nerve to the abductor digiti minimi has also been implicated in the etiology of plantar heel pain. Chronic inflammation and subsequent changes in the plantar fascia may predispose a person to nerve entrapment. A heel spur also may play a role in the development of an entrapment neuropathy of the nerve to the abductor digiti minimi because this nerve passes close to the bony ridge of the medial calcaneal tubercle, the site of the spur, if present. Chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and thickening of the plantar fascia at its origin, with formation or growth of a heel spur, may cause compression of the nerve (Fig. 49-2).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The most common etiology of plantar heel pain is plantar fasciitis, an inflammation of the plantar fascia at its insertion on the calcaneus. Additional etiologies include stress fractures and entrapment of the lateral plantar nerve. More remote causes are fracture, calcaneal periostitis, plantar fascia rupture, fat pad syndrome (heel pad atrophy), seronegative spondyloarthropathies, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis. The painful heel syndrome remains a difficult problem to manage because of its protracted clinical course. Fortunately, 90% of the patients respond to conservative measures, leaving just 10% who require further evaluation and consideration for surgical intervention (Davis et al, 1994).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The diagnosis of plantar fasciitis can generally be made on clinical grounds with a careful history and physical exam:

Unilateral medial plantar pain in patients (70% to 80%)

Gradual onset

Aching or burning

Maximal pain during the first few steps from bed or from rising after prolonged sitting

Pain initially improves after 5 to 10 minutes of walking

Pain recurs as the day progresses

Training errors or sudden increase in activity

Occupation that requires a lot of standing or walking

Sudden weight gain

Localized tenderness at the insertion of the plantar fascia onto the medial tubercle of the calcaneus

Thickened, tight, or nodular plantar fascia

Biomechanical abnormalities—pes planus (flat foot), pes cavus (high arch), excessive pronation

Worsening of pain with passive dorsiflexion of toes

Restricted dorsiflexion of the ankle from tight Achilles tendon or soleus and gastrocnemius muscles.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

The typical patient with plantar heel pain describes pain that is of gradual onset, not associated with a specific traumatic event. In the nonathletic patient, the pain may occur spontaneously,

or it may follow a sudden weight gain, the start of an exercise program, or a sudden increase in activity. It is a common condition late in pregnancy. In athletes, the condition is usually related to training errors such as rapidly increasing the mileage, intensity, or duration of workouts, running on steep hills, changing shoes or training surfaces, and biomechanical factors (Davis et al, 1994). The continued use of shoes with a badly worn heel also contributes to the development of plantar fasciitis.

or it may follow a sudden weight gain, the start of an exercise program, or a sudden increase in activity. It is a common condition late in pregnancy. In athletes, the condition is usually related to training errors such as rapidly increasing the mileage, intensity, or duration of workouts, running on steep hills, changing shoes or training surfaces, and biomechanical factors (Davis et al, 1994). The continued use of shoes with a badly worn heel also contributes to the development of plantar fasciitis.

The pain is usually localized to the plantar medial aspect of the heel at the site of the plantar fascial attachment to the medial tubercle of the calcaneus (DeMaio et al, 1993). Radiation of the pain into the arch and the medial side of the foot occasionally occurs. The pain is described as burning or aching and will gradually worsen if left untreated.

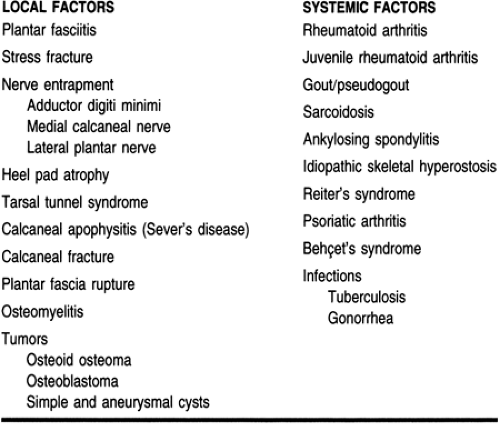

Patients characteristically complain of pain that is maximal during the first few steps from bed or from rising after prolonged sitting. This pain eases after 5 to 10 minutes of walking but recurs later in the day with normal activities, especially with walking on concrete or hard surfaces. The condition is usually not disabling, but it may limit weight-bearing activities, especially running and jumping. The pain is usually unilateral; therefore, if bilateral heel pain occurs, a systemic disorder must be ruled out (Table 49-1).

The physical exam should include the entire lower extremity, with attention to the anatomic and biomechanical factors that predispose to plantar fasciitis. The patient should be examined standing and walking to evaluate the arch during weight bearing. This may reveal the existence of static biomechanical abnormalities such as pes planus and pes cavus, or an abnormality of gait such as excessive pronation of the foot. Range of motion testing, motor and sensory testing, vascular evaluation, and palpation for the location of tenderness should be included in the exam.

Localized tenderness at the insertion of the plantar fascia onto the medial tubercle of the calcaneus is pathognomonic for plantar fasciitis. Tenderness less commonly occurs in the medial longitudinal arch of the foot and the central heel. Passive dorsiflexion of the toes and ankle, or having the patient stand on the toes, may reproduce or worsen symptoms by tightening the plantar fascia (Davis et al, 1994; Karr, 1994). Passive abduction and eversion of the foot is another provocative test that indicates involvement of the lateral plantar nerve (Davis et al, 1994). Patients often have restricted dorsiflexion of the ankle because of a tight Achilles tendon or gastrocnemius and soleus muscle tightness. Localized swelling is usually absent, but the plantar fascia may be thickened, tight, or nodular (Seto & Brewster, 1994).

Other etiologies for plantar heel pain (see Table 49-1) must be excluded. If the pain has an acute onset and there is localized swelling or ecchymosis of the plantar fascia or heel, the provider must suspect a calcaneal fracture or plantar fascia rupture. The latter is also associated with prior corticosteroid injection into the planter fascia (Sellman, 1994). A patient with tarsal tunnel syndrome will have a burning pain radiating into the toes that is worse at night and is often associated with paresthesias and motor deficits. It is more common in women, and there should be a Tinel’s sign over the tarsal tunnel. Systemic inflammatory disorders are not uncommon in patients with plantar heel pain. Patients with seronegative spondyloarthropathies are especially prone to develop plantar heel pain, and the foot is second only to the knee as the site of initial presentation in rheumatoid arthritis. Gout can also cause plantar fascia inflammation. These should be ruled out if the provider is clinically suspicious or if a course of treatment 6 to 12 months long produces no results.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree