CHAPTER 30 Pericardial Disease

Introduction

This chapter will focus on the issues outlined above. References that are to review papers are indicated as such in the text or citations. Physicians in charge of patients in a CICU must be aware of disorders of the pericardium because pericardial disease may simulate disease of the heart itself and lead to incorrect diagnosis and treatment. In the most extreme cases, this error may have fatal consequences. It remains as true today as when Osler1 first made the observation that pericardial disease is a frequently missed diagnosis. Especially in a CICU, pericardial disease is much less common than myocardial disease; therefore the best way to recognize pericardial disease is to maintain a high index of suspicion for this possibility when the cause of right heart failure or precordial pain is not readily apparent. The principal manifestations of pericardial disease simulating ischemic heart disease are listed in Table 30-1.

Table 30–1 Major Ways in Which Pericardial Disease May Simulate Ischemic Syndromes

| Pericardial pain simulating ischemic pain |

| ST segment deviation suggesting myocardial ischemia |

| Dressler syndrome mistaken for reinfarction |

| Cardiac tamponade misinterpreted as heart failure |

| Severe tamponade mistaken for cardiogenic shock |

| Friction rub mistaken for murmur of acute mitral regurgitation |

| Friction rub mistaken for murmur of rupture of the ventricular septum |

Pericardial Syndromes in Ischemic Heart Disease

Chest Pain

A significant proportion of patients experience some type of chest pain in the first day or so after acute myocardial infarction. The most important cause of recurring chest pain in patients in the CICU with a documented acute myocardial infarction is myocardial ischemia, which often demands therapeutic action; however, not all chest pain occurring under these circumstances is so ominous. Many episodes of such pain elude diagnosis, especially those that are the result of the patients’ natural apprehension and the understandable way in which they become sensitized to any abnormal sensations in the chest. Pulmonary infarction, embolism, or other conditions associated with pleuritic or substernal pain are included in the differential diagnosis. The cause of pleuritic chest pain can often be established from the clinical examination and the chest radiogram, but pleuritic pain may be a symptom of post–myocardial infarction pericarditis. Unfortunately, the pain of pericarditis is not always pleuritic in nature, but may simulate or be indistinguishable from pain of myocardial origin. The symptom may also have characteristics of both myocardial and pericardial pain; for instance, it may be a crushing sensation, yet be aggravated by inspiration, influenced by posture, or be referred to the trapezius ridge. It would be desirable to be able to rely on the electrocardiogram to distinguish with certainty between pericardial and myocardial pain, but the typical changes of acute pericarditis often are not recognizable against a background of the changes associated with acute myocardial infarction or active ischemia.2

Acute Pericarditis

A number of comprehensive reviews of this subject have been published in recent years.3–9 Acute pericarditis most commonly is an acute infection of the pericardium and superficial myocardium (epicardium) that is adherent to the visceral pericardium. Acute viral pericarditis is a self-limiting relatively short disease that responds rapidly to anti-inflammatory treatment and therefore is classified as low risk for an early complication, most importantly cardiac tamponade, although tamponade does complicate about 1% to 2% and requires drainage to prevent a fatal outcome. In striking contrast is acute pericarditis of other etiologies, including infection with any living organism. Of special relevance to this chapter are pyogenic and tuberculous infection and acute pericardial injury of etiology other than that caused by viral infection. Examples include trauma including surgical or percutaneous intervention. The only common late complication is unpredictable recurrence that occurs at various intervals repeated over a highly variable period of time in 15% to 30% of patients (recent review papers).8,9

Almost all patients complain chiefly of chest pain, but they may have few if any risk factors for coronary disease. They are often quite young and report a prodrome described as very like the flu. This prodromal event is febrile and very different from the feeling of general malaise that may precede acute myocardial infarction. Once the receiving physician considers it likely that a patient has acute pericarditis, evaluation and initial management should be done in a same-day unit,10 otherwise, hospital admission is necessary. The initial assessment can be completed in 24 hours and comprises enquiry about the details of the chief complaint (chest pain), any other symptoms, past medical history, standard biochemical laboratory tests, including C-reactive protein, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and markers indicating myocardial inflammation.

Biomarkers

Acute pericarditis is associated with increased levels of serum biomarkers for myocardial injury, including modest elevations of creatine kinase (CK-MB) and serum cardiac troponin I (cTnI).11–13 Serum cTnI is detectable in 32% to 49% of patients and exceeds the threshold value of 1.5 ng/mL in 8% to 22%. Mild increases in cTnI often occur in the absence of elevations in CK-MB. The rise in serum cTnI in acute pericarditis is roughly related to the extent of concurrent myocardial inflammation and is transient, resolving within 1 week. Persistent cTnI elevation suggests ongoing epicardial inflammation. Patients with a rise in cTnI do not, however, have a higher incidence of complications. Laboratory signs of inflammation are diagnostic criteria for acute pericarditis. These include the elevated white blood cell count erythrocyte sedimentation rate and, most important, serum C-reactive protein concentration.

Features suggesting high risk for an early complication are:

Two pericardiopathies may occur after an acute myocardial infarction. The more frequent but less ominous is acute pericarditis with or without a benign small effusion. This acute pericarditis occurs early in the course, the peak incidence being at 3 days. This is a manifestation of contiguous pericardial inflammation over the region of the infarction and is thus more a feature of Q-wave than non–Q-wave infarctions. Using clinical criteria, a pericardial friction rub used to be reported in about 10% of patients after acute myocardial infarction2 but is considerably more common in autopsy series. Pericardial friction rubs are most commonly detectable on the third day after the onset of infarction but sometimes are heard as early as the first day postinfarction. The rub has a tendency to be evanescent; therefore, if it is to be detected reliably, frequent careful auscultation focused on its detection is necessary.

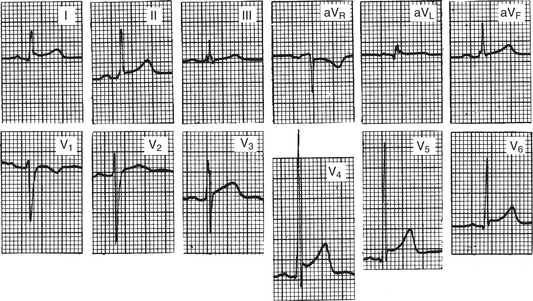

Pericarditis may exaggerate the degree of ST segment elevation in acute myocardial infarction.14,15 ST segment elevation in leads in which reciprocal depression would be anticipated is suggestive of complicating generalized pericarditis;16 thus ST elevation is concordant (Fig. 30-1). When pericarditis, with or without effusion, complicates myocardial infarction, evolution of the T-wave changes may be atypical, with the T wave remaining or becoming positive when T-wave inversion would be anticipated in an uncomplicated infarction.17

Pericardial Effusion

Pericardial effusion after myocardial infarction, when specifically sought by serial echocardiography, is surprisingly common,18 occurring in about one fourth of the patients. Another unexpected feature of pericardial effusion as a sequel of myocardial infarction is that it persists for several weeks and bears no relation to pericardial friction rub. Pericarditis and pericardial effusion are associated with a worse prognosis, probably because they are more common after large infarctions, which tend to be anterior, and usually transmural.18–20 It is accepted practice to avoid administering anticoagulants or thrombolytic agents to patients with active or recent inflammatory pericarditis,21 but both the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell’Infarcto Miocardio (GISSI)20,21 and the Thrombolysis and Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (TAMI) trials22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree