Osteoarthritis

Dennis A. Cardone DO

Alfred F. Tallia MD, MPH

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a clinical condition of diarthroidal joints characterized by pain, stiffness, and structural alteration. Underlying this condition are destruction and abnormal repair of articular cartilage, followed by deposition of new bone and cartilage at the margins of the joint. The process may lead to joint deformity, decreased range of motion, and in later stages severe functional impairment. Although all diarthroidal joints may be affected, OA is most commonly seen in hand, hip, and knee joints.

Primary care providers are at the front line of diagnosing and treating OA. The national ambulatory medical care survey reveals that problems of the musculoskeletal system are one of the most frequent reasons for office visits. With proper attention to details of diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes, the primary care provider is best suited to care for patients with OA and to coordinate the use of other specialists.

The pain of OA is characteristically worsened with activity and relieved by rest. Conversely, the stiffness associated with OA is worse after rest of the affected joint and better with motion. The bony structural alteration of joints associated with OA and seen in radiographic studies may or may not be associated with pain or stiffness. Hence, the diagnosis of OA is clinically based on more than just the radiologic features of a joint.

OA is classified as either primary/idiopathic (without a discernible explanatory event such as joint trauma) or secondary (to a specific insult to the joint). OA may affect one or more joints simultaneously. Although OA is not characterized as a systemic inflammatory illness, recent studies have suggested a local inflammatory component to this protean condition (Smith et al, 1997).

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

Three types of joints exist within the body: diarthroidal or synovium-lined joints, which are involved in the movement of limbs; synarthrosis or pseudojoints; and amphiarthroses or cartilaginous joints. OA is a disease strictly of diarthrodial joints. Examples of diarthrodial joints are the knee, hip, and joints of the hands. The bony articular prominences of diarthrodial joints are lined by articular cartilage, which facilitates motion at the joint. The biochemical composition of adult cartilage is roughly 70% water and 30% solids. Current understanding of the pathophysiology of OA suggests that articular cartilage trauma, possibly complicated by normal aging, results in alteration of the water/solid ratio. An inflammatory process involving a variety of biochemically initiated cellular events leads to cartilage breakdown. Further joint response leads to changes in bone, resulting in osteophyte formation and bone reconstruction. The exact role that aging plays in OA is uncertain.

Joint remodeling occurs initially at the edge of the affected joint. Osteophyte formation (new bone at the edge of joints) is thought to be the result of endochondral ossification of existing and new cartilage. The relation between osteophyte formation and the development of clinical symptoms is not known. Osteophytes are often present in radiologic studies of asymptomatic persons and may represent a normal response to a variety of joint stressors. Osteophyte formation and other bone remodeling, however, are generally present in advanced OA.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

OA is thought to result from a complex interplay between a variety of host-specific characteristics, such as immunologic, biomechanical, or bioinflammatory variables, and functional characteristics, such as joint use, environmental trauma, or stresses. OA is the most prevalent joint disease.

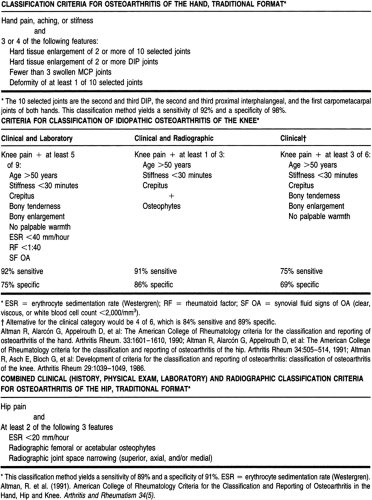

Within the past 15 years, the American College of Rheumatology has developed and published criteria for the classification of OA of the knee, hip, and hand (Table 47-1). These criteria have proven helpful in establishing a uniform definition for the diagnosis and the extent to which the condition is present within populations. Efforts to discern the prevalence and incidence of OA in this country and worldwide have been hampered by the lack of such a definition.

Exact data are lacking, but the overall incidence of OA appears to increase with age. Because of the chronicity of the condition, prevalence also increases with age. OA is the most prevalent chronic condition in middle and older adulthood (Verbrugge, 1995). In general, age and gender are the most important risk factors for OA, with the rate for women exceeding that of men at all ages (Hughes & Dunlop, 1995; Verbrugge, 1995).

Death associated with OA is most often a direct result of functional impairment of the joint and resulting injury or immobility. The complications associated with OA, at least in terms of its economic affect, and the overall financial impact of musculoskeletal conditions are both high. Given the aging of the population in the United States, and the resultant increase in the prevalence of OA, the financial impact of this illness can be expected to rise in the next 20 to 30 years. There is a significant earning loss from work disruption in patients with OA less than 65 years old. Specific risk factors associated with OA include:

Age: Prevalence is directly related to advancing age.

Obesity: Although the exact mechanism has yet to be described, overweight people have higher rates of OA of

the hips and knees (Felson, 1996). Although this may make biomechanical sense in terms of the increased stress that being overweight may place on these joints, what is less well understood is the increased association between obesity and hand OA. It is suspected but not clinically proven that weight loss may be an opportunity for clinical prevention of OA in later ages.

Exercise: Several studies have suggested a link between specific forms of exercise and sports and OA (Lane & Buckwalter, 1993), but none have been conclusive. More recent research has suggested that exercise may have a beneficial effect in the treatment of established OA. Given the multiple beneficial effects of exercise on other aspects of health, recommendations for the curtailment of specific types of exercise to reduce the risks of OA seem unwarranted. More recent studies suggest just the opposite—that exercise in moderate forms may be beneficial in primary prevention.

Genetics and family history: The genetic risk for the development of OA is likely to involve multiple genes (Cicuttini & Spector, 1996; Jimenez & Dharmavaram, 1994). Familial tendencies in the development of joint deformities such as Heberden’s nodes were first described earlier this decade. Although genetic factors are most likely polygenic,

specific gene mutations resulting in changes of joint components that may lead to the development of OA also have been described. For example, a variety of collagen disorders linked to gene defects are thought to be involved in the development of certain forms of OA. As the molecular genetic revolution progresses, more genes will be elucidated as playing a role in this disease. In the interim, more research on the complex interaction between genetics and family history and environment needs to be performed.

Occupation: Occupation is a risk factor for OA (Creamer & Hochberg, 1997) Work-related activity has been linked to the development of OA of the knee and other joints. This is thought to be the result of repeated minor trauma, exacerbating an already increased risk at a joint predisposed from underlining mechanical factors such as joint deformity or malalignment.

Trauma: A history of major trauma to the knees is strongly associated with the development of OA. The same is true for injuries to other joints. In general, any injured joint is at risk for the later development of OA.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

Pain is the most common presenting complaint in OA. The pain is usually localized to the involved joint, but it may be referred. An example of referred pain is cervical OA presenting as pain in the shoulder, or lumbar facet joint OA causing pain in the buttock or hip regions. Early in the course of OA, pain may have a nagging or aching quality that varies in intensity according to the level of activity. Pain usually occurs with activity or motion and is relieved by rest. In early disease, the pain is not severe, but as the disease progresses pain may be present with minimal motion or even at rest.

Stiffness is very common. Early in the disease, it is felt when the patient resumes activity after a period of rest, and later it may become a permanent complaint. Bony swelling and joint deformity, especially of affected knees and interphalangeal joints, are common later in the disease. Muscle wasting, bowing of the legs, and knock knees are also late manifestations. Bony swelling of the interphalangeal joints may make it difficult to perform activities requiring fine motor skills, such as writing, as well as gross motor skills, such as opening jars or grasping objects. Patients complain of loss of function according to the site involved.

The cause of pain in OA may include muscle spasm and fatigue, joint contracture, capsular fibrosis, and in some cases mild to moderate synovitis. Acute inflammatory flares can be related to trauma or crystal-induced synovitis.

On the physical exam, there may be multiple joints involved. The patient’s gait should be evaluated for disturbances related to OA of the hip and knees. A limp or stiff-kneed gait may be present. Bony swelling and deformity are usually easily recognized, especially at the interphalangeal joints of the hand and the knees. In the later stages of the disease, muscle wasting may become obvious. During acute flares, there may be signs of inflammation, including erythema, warmth, and swelling. Passive joint motion is restricted and painful, and there may be crepitus or a feeling of crackling as the joint is moved through its range of motion. On palpation, joint tenderness, intra-articular effusions, synovial thickening, and marginal osteophytes may be present. In most cases, there is no joint instability.

Hand

The most commonly affected joints of the hand are the first carpometacarpal joint and the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints. Heberden’s nodes are spurs formed at the distal interphalangeal joints. Bouchard’s nodes are present at the proximal interphalangeal joints. Deformity or loss of motion tends to be gradual (Fig. 47-1). There is a lateral deviation of the joints involved. Hand OA may progress or remain stable over time. The progression is usually fastest in the distal interphalangeal joints. When the first carpal metacarpal joint is involved, there is tenderness at the site and later a squared appearance of the hand. The trapezioscaphoid joint is also commonly involved. Metacarpophalangeal involvement is rare. Despite the development of bony deformities, function of the hands remains relatively good.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree