OLIGOMENORRHEA

JEANNINE DEL PIZZO, MD, JENNIFER H. CHUANG, MD, MS, AND JAN PARADISE, MD

Oligomenorrhea, or infrequent menstrual bleeding, can usually be evaluated and managed in the outpatient setting. The pediatric emergency physician should be familiar with the common causes of oligomenorrhea as well as those presenting with true medical emergencies. This chapter will focus on how to evaluate a child presenting with oligomenorrhea, and when and where to refer.

DEFINITIONS

Although this chapter will focus on the approach to an adolescent with infrequent menstrual bleeding, the term “oligomenorrhea” is no longer used by the FIGO World Congress of Gynecology and Obstetrics nor by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. For the pediatric emergency physician, oligomenorrhea can be defined as an interval of more than 6 weeks between two menstrual periods. The newly accepted term of infrequent menstrual bleeding refers to one to two episodes of menstrual bleeding in a 90-day period. If menstrual cycles do not resume within 3 to 6 months, the term secondary amenorrhea is applied. Some patients with anovulatory menstrual cycles have oligomenorrhea punctuated by episodes of excessive bleeding. An approach to the evaluation of abnormal vaginal bleeding is presented in Chapter 75 Vaginal Bleeding.

This chapter will not specifically discuss primary amenorrhea—that is, failure to menstruate by a specified age, often 16 years. However, some disorders discussed here can also produce primary, as well as secondary amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea as part of an overall delay in pubertal development.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

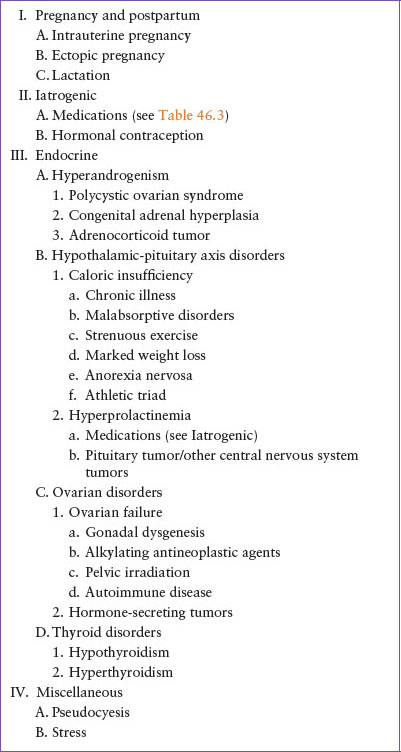

The differential diagnosis of oligomenorrhea is given in Table 46.1.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

History

The initial approach to any female complaining of oligomenorrhea should begin with history. It is essential to keep in mind that children and teenagers may not feel comfortable sharing certain information in front of their parents or caregivers. The emergency physician should plan on obtaining a history both with parents or caregivers present and with the patient alone. Some patients may feel comfortable discussing sexual information in front of parents and caregivers, however others will prefer to keep this information confidential.

Past medical history and current medications should be noted. A brief menstrual history should be obtained including onset of menstruation, timing of the last menstrual period, duration and frequency of typical menstruation cycles, number of pads or tampons used in a day, bleeding in between cycles, and the presence and size of clots passed. A patient should be asked if she engages in vaginal intercourse with males, if and which birth control methods are used, and if she is currently or has ever been pregnant. Patients should be asked if they have any recent weight loss or are restricting their caloric intake, increasing their physical activity, self-inducing vomiting, or using any medications (laxatives, diet pills, ipecac) for the purpose of weight loss.

Pertinent historical factors that can help exclude potentially dangerous causes of oligomenorrhea include any indicators of acute abdomen such as presence of abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, fever, or loss of appetite. Ascertain symptoms of increased intracranial pressure such as change in vision, neurologic symptoms, early morning emesis, or headache that is persistent, worsening, or waking the patient from sleep. Inquire about the presence of palpitations, tachycardia, sweating, weight loss, or agitation that may suggest hyperthyroidism. Conversely symptoms of hypothyroidism such as weight gain, cold intolerance, fatigue, and depressed mood should also be obtained.

Examination

Vital signs should be noted including the patient’s height, weight, and body mass index (BMI). Tachycardia and hypotension may raise suspicion for ectopic pregnancy. Papilledema, blurred vision, cranial nerve VI palsy, visual field deficits, or other focal deficits may indicate increased intracranial pressure associated with pituitary tumors. Bradycardia and hypotension may suggest malnutrition due to caloric restriction, purging, or excessive energy expenditure. Note general appearance, mental status and perfusion, and perform a general examination. The patient should be observed for features such as overall body habitus, hirsutism, acanthosis nigricans, and acne. An abdominal examination should concentrate on the presence of peritoneal signs, a gravid uterus, or a palpable mass. Pubertal development including breasts and genitalia should be checked. If a history of galactorrhea is suspected, attempt to express fluid manually from the patient’s breasts. The completed examination will separate the majority of patients who have no notable abnormalities from a minority with that point to a specific medical cause.

Pregnancy

Pregnancy is the first diagnosis to consider when evaluating an adolescent with one or several missed menstrual periods (Fig. 46.1). If the patient is not pregnant, evaluation can proceed at a more deliberate pace. Prompt diagnosis and referral are important; early and regular prenatal care is associated with reduced morbidity and mortality among pregnant teenagers and their offspring; early diagnosis also affords the pregnant adolescent time to consider all options including therapeutic abortion.

TABLE 46.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF OLIGOMENORRHEA

Early pregnancy is not always easy to recognize. Symptoms of fatigue, nausea, vomiting (not necessarily in the morning), urinary frequency, and breast growth or tenderness are common but by no means universal or specific. Some patients may report the result of a home pregnancy test. However, because of variability in the test’s sensitivity for detecting urinary human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), home pregnancy test kits commonly give falsely negative results. False-positive results can also occur, though rarely. Accordingly, the emergency physician should not rely solely on the reported result of a home pregnancy test to make or to exclude the diagnosis of pregnancy.

Qualitative urine and serum pregnancy tests performed in medical settings generally detect the β-subunit of hCG (β-hCG). The urine pregnancy test threshold is generally at β-hCG levels of ≥20 mIU per mL and will permit the detection of a normal pregnancy within about 10 days after conception and, in most but not all cases, by the time an expected menstrual period is missed. Serum β-hCG can be detected at lower levels though laboratories are variable regarding the level of detection (<1 vs. <5 mIU per mL). The emergency physician should know the detection level of the quantitative and qualitative β-hCG tests used by the local laboratory. Ectopic pregnancies often produce abnormally low levels of β-hCG compared to an intrauterine pregnancy of the same gestational age (see Chapter 75 Vaginal Bleeding). If a patient with one or several missed menstrual periods also complains of abdominal pain or abnormal vaginal bleeding, the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy must be entertained (see Chapters 100 Gynecology Emergencies and 127 Genitourinary Emergencies). Although more than half of women with ectopic pregnancy have no risk factors, prior infections with chlamydia and gonorrhea, and pelvic inflammatory disease all increase the likelihood that a subsequent pregnancy will be ectopic.

Evaluation of Nonpregnant Patients

After pregnancy is excluded, the evaluation of an adolescent with oligomenorrhea can proceed at a deliberate pace (Fig. 46.1)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree