Neuropathic Pain

Nerves send sensory impulses to the brain for interpretation. These impulses travel in a regular pattern when the nervous system is working properly. When injured, this regular controlled transmission of impulses fails and nerves fires aberrantly. Injured nerves, no longer triggered solely by appropriate stimuli, develop pathologic activity manifesting as abnormal excitability to normal chemical, thermal, and mechanical stimuli. The brain interprets this aberrant nerve firing as pain. With neuropathic pain, the patient usually reports an electric, shooting, burning pain rather than an achy, dull pain.

This chapter presents the most universal high-yield causes of neuropathic pain in different parts of the body. To learn the particulars of how to properly prescribe medications or perform procedures mentioned in this chapter, it is necessary to refer to the chapter dedicated to the specific subject.

Pain in the Face: Trigeminal Neuralgia

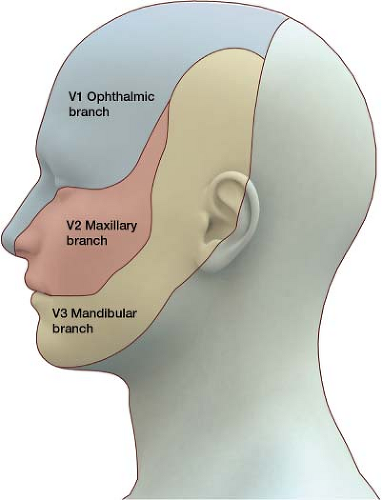

In the world of pain, one of the most severe forms is trigeminal neuralgia (tic douloureux, meaning painful spasm). This pain can be so severe that it has been known to cause suicide. The trigeminal nerve, or the fifth cranial nerve, which is responsible for sensory impulses originating from the face above the jaw line, has three branches: Ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular (V3) (Fig. 2-1). The pain of trigeminal neuralgia is most common in the V2 and V3 branches of the trigeminal nerve. It is a sharp, electric pain that radiates deep into the cheek, lips, and tongue, typically on one side of the face. During an attack, any sensory stimuli, even a stream of fast-moving air, may exacerbate the pain. Theories about the cause of trigeminal neuralgia remain controversial. One prevailing theory is that a small blood vessel wrapped around the branches of the trigeminal nerve causes periodic compression, leading to aberrant nerve firing.

History and Examination

The diagnosis is primarily based on history. Patients describe the pain as brief, stabbing, and shock-like. Exacerbations often come in clusters, with complete remission that may last months to years. Pain is

unilateral; examination should confirm that pain is in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. When patients present with symptoms that go past the midline of the face or the jaw line, it is important to check for another cause of the pain. When a young person presents with trigeminal neuralgia, this may be the first sign of multiple sclerosis; a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with contrast is used to investigate this possibility. Other than pain, physical examination findings are normal. The practitioner should ask about a vesicular outbreak in the area to rule out postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

unilateral; examination should confirm that pain is in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. When patients present with symptoms that go past the midline of the face or the jaw line, it is important to check for another cause of the pain. When a young person presents with trigeminal neuralgia, this may be the first sign of multiple sclerosis; a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with contrast is used to investigate this possibility. Other than pain, physical examination findings are normal. The practitioner should ask about a vesicular outbreak in the area to rule out postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

Treatment

Tegretol (carbamazepine) and Lyrica (pregabalin) are useful in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Baclofen, a muscle relaxant, can be very beneficial. Opioids have been employed in combination with the above medications. Trigeminal nerve blocks can provide relief during painful exacerbations. In microvascular decompression, also known as the Jannetta procedure, a surgeon explores the nerve for an encroaching blood vessel. If found, it is necessary to separate (“decompress”) the vessel and nerve with a surgical pad.

Pain in the Thumb, Index, Middle, and Half of the Ring Finger: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

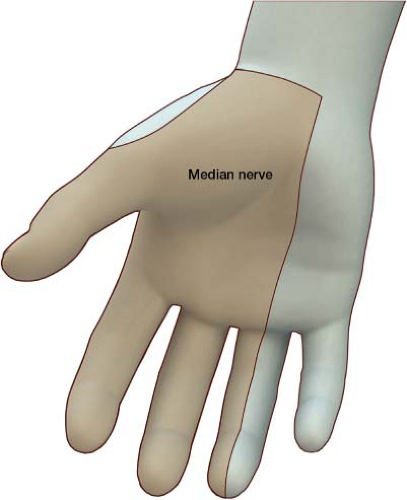

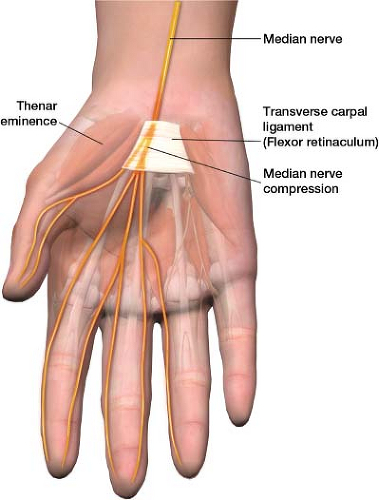

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is one of the most common causes of pain in the hand. It results from compression of the median nerve under the transverse carpal ligament (Fig. 2-2). CTS leads to an irritable electric sensation in the distribution of the median nerve (Fig. 2-3). Symptoms may be unilateral or bilateral. Upon waking, people may feel as if the affected hand is asleep. In severe cases, atrophy of the thenar eminence (muscle at the base of the thumb) may eventually occur. Two medical conditions associated with CTS are pregnancy and hypothyroidism. In these conditions fluid retention in tissues may exacerbate this compressive neuropathy.

History and Examination

Patients describe an electric, painful sensation in the palm, thumb, index, middle, and half of the ring finger. If a patient has pain in the neck that radiates down through the arm into the hand, the diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy should be entertained. If there is numbness of the whole hand bilaterally, it is necessary

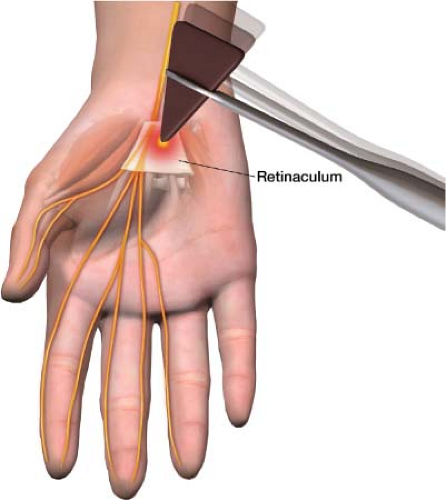

to consider peripheral neuropathy. The existence of paresthesia (an abnormal sensation in the skin, such as numbness, tingling, pricking, or burning) in the pinky and ring finger is more indicative of ulnar neuropathy. On examination, tapping on the median nerve (Tinel sign, Fig. 2-4) or compressing the nerve using Phalen maneuver (Fig. 2-5) can elicit the symptoms of CTS. A nerve conduction study shows increased latency of the median nerve.

to consider peripheral neuropathy. The existence of paresthesia (an abnormal sensation in the skin, such as numbness, tingling, pricking, or burning) in the pinky and ring finger is more indicative of ulnar neuropathy. On examination, tapping on the median nerve (Tinel sign, Fig. 2-4) or compressing the nerve using Phalen maneuver (Fig. 2-5) can elicit the symptoms of CTS. A nerve conduction study shows increased latency of the median nerve.

Figure 2-2 Compression of the median nerve, under the transverse carpal ligament (flexor retinaculum). Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS). |

Figure 2-4 Tinel sign. Percussion at the transverse carpal ligament (flexor retinaculum) produces paresthesia along the path of the median nerve. |

Treatment

Because CTS is a mechanical problem, wrist splints may relieve the compression. Wrist splints are available at most pharmacies. Normally, when people sleep, the wrist is in a flexed position, narrowing the carpal tunnel for hours. To alleviate symptoms patients wear a wrist splint at night, placing the wrist in a neutral position. Typically, antiseizure and antidepressant medications used to treat neuropathic pain can also help. An injection into the area of compression, a steroid mixed with a local anesthetic, can provide pain relief as well. Some 25% of patients will have long-term relief of their symptoms following a CTS nerve block.1 Surgery consists of cutting the transverse carpal ligament to relieve the compressive neuropathy.

Pain in the Thoracic Region: Postherpetic Neuralgia

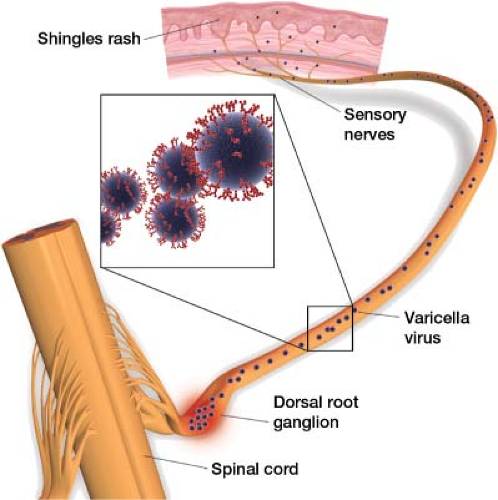

A common, often missed, cause of burning pain across the abdomen or chest is PHN. This type of neuralgia (pain along the course of the nerve) begins after an outbreak of herpes zoster (shingles). The cause of herpes zoster is a dormant varicella virus harbored in the

dorsal root ganglion that is reactivated (Fig. 2-6). The virus spreads along the nerve, presenting as pain, itching, and tingling along the dermatome in which it spreads. Vesicle formation follows (Fig. 2-7). After the acute phase, the vesicles from the herpes rash begin to crust over. For most people, this is the end of the painful symptoms, but roughly 20% go on to develop PHN. Less than 10% of people younger than age 60 develop PHN, whereas about 40% of people older than 60 do. African Americans are 75% less likely than whites to develop this condition. Typically, the pain follows a thoracic dermatome, but it can follow any dermatome. If the pain lasts more than a month, it is defined as PHN. Sensation may be altered over this area, with the patient experiencing either hypersensitivity or decreased sensation.

dorsal root ganglion that is reactivated (Fig. 2-6). The virus spreads along the nerve, presenting as pain, itching, and tingling along the dermatome in which it spreads. Vesicle formation follows (Fig. 2-7). After the acute phase, the vesicles from the herpes rash begin to crust over. For most people, this is the end of the painful symptoms, but roughly 20% go on to develop PHN. Less than 10% of people younger than age 60 develop PHN, whereas about 40% of people older than 60 do. African Americans are 75% less likely than whites to develop this condition. Typically, the pain follows a thoracic dermatome, but it can follow any dermatome. If the pain lasts more than a month, it is defined as PHN. Sensation may be altered over this area, with the patient experiencing either hypersensitivity or decreased sensation.

Figure 2-7 Shingles rash. (From: Craft N, Fox LP, Goldsmith LA, et al. Visual Dx: Essential Adult Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.) |

History and Examination

Patients describe a burning pain, electric in nature with exquisite sensitivity of the skin that follows a dermatome. Often patients have a significant deterioration in quality of life. On examination, the patient may have scars from previous vesicles. However, it is important to remember that on rare occasions, PHN can occur without any previous vascular rash. In this instance, the nerve is affected by reaction of the virus, but it never clinically manifests at the skin level.

Treatment

Aggressive treatment during the acute outbreak can sometimes prevent progression to PHN. Acyclovir is effective in reducing the length of time of the acute outbreak of lesions and in decreasing pain and promoting healing.2,3 Antiseizure and antidepressant medications used for neuropathic pain are first-line treatment. A 5% Lidoderm (lidocaine) patch over the area is a reasonable treatment option with a low–side-effect profile. Epidural steroid injections may be effective. (The author often performs a series of three epidural steroid injections, 1 to 2 weeks apart.) In Forrest’s study, the use of epidural steroid injections at weekly intervals for people who have had PHN for more than 6 months provided 89% of the patients complete relief from their pain at 1 year. This study did not have a control group.4 For patients who do not respond to medications and injections, a spinal cord stimulator trial is a reasonable next step.

Pain in the Back or Neck and Down the Leg or Arm: Radicular Pain

One of the most common pain complaints is radicular pain (irritation of a nerve root). When the spinal cord is affected, this is referred to as a myelopathy. If only the nerve root is involved, it is radiculopathy without signs of myelopathy. (When radiculopathy occurs in the lumbar spine, some refer to this as sciatica.) The pain radiates along the path of the nerve root being irritated. In the lower extremities, people may describe it as pain that starts in the lower back/buttocks and radiates down one or both legs. In the upper extremities, people may describe it as cervical pain that radiates down one or both arms. The most common cause of radicular pain is a herniated disc that affects a nerve root.

To better understand this, it helps to take a closer look at the anatomy involved with radicular pain from

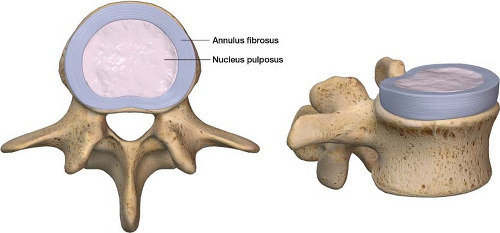

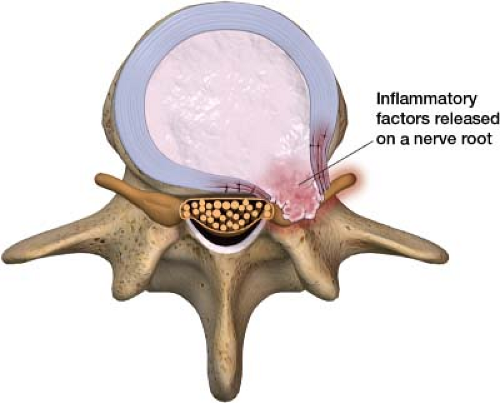

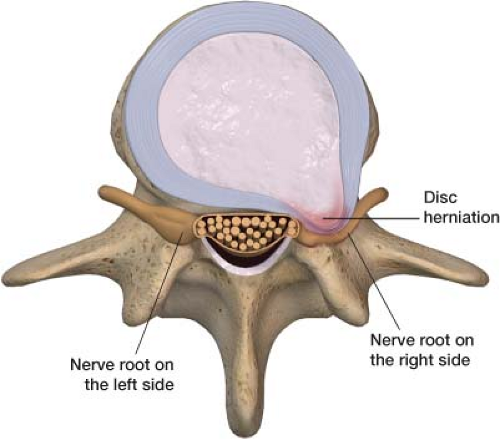

a herniated disc. A vertebral disc is shaped like a jelly donut; the jelly-like inner part is the nucleus pulposus and the thick outer part is the anular fibrosus (Fig. 2-8). The nucleus pulposus, the jelly-like inner part of a vertebral disc, contains inflammatory factors such as substance P and nitrous oxide. When the nucleus pulposus starts to leak out through the outer layer of the disc (annular fibrosus), it results in an inflammatory reaction around the nerve root (Fig. 2-9).5 When a disc herniates out of its normal position and/or releases its inner inflammatory content, it can affect the nerve root at that location. If the disc or the inflammatory content is herniating to just one side of the spinal column, it can affect only the ipsilateral nerve root, leaving the contralateral nerve root alone. This is why some people have pain radiating down both legs and some down one leg only (Fig. 2-10). It is generally theorized that either physically compressing the nerve root and/or bathing it in this inflammatory matrix is the cause of radicular pain. Inflammation and physical protrusion of the disc can go on to cause pressure on the epidural venous plexus, causing venous obstruction.6 When the venous side backs up, it can lead to decreased perfusion of the nerve root from the arterial side. Prolonged irritation and poor blood circulation appear to make these nerve roots hypersensitive,7 further contributing to prolonged radicular pain.

a herniated disc. A vertebral disc is shaped like a jelly donut; the jelly-like inner part is the nucleus pulposus and the thick outer part is the anular fibrosus (Fig. 2-8). The nucleus pulposus, the jelly-like inner part of a vertebral disc, contains inflammatory factors such as substance P and nitrous oxide. When the nucleus pulposus starts to leak out through the outer layer of the disc (annular fibrosus), it results in an inflammatory reaction around the nerve root (Fig. 2-9).5 When a disc herniates out of its normal position and/or releases its inner inflammatory content, it can affect the nerve root at that location. If the disc or the inflammatory content is herniating to just one side of the spinal column, it can affect only the ipsilateral nerve root, leaving the contralateral nerve root alone. This is why some people have pain radiating down both legs and some down one leg only (Fig. 2-10). It is generally theorized that either physically compressing the nerve root and/or bathing it in this inflammatory matrix is the cause of radicular pain. Inflammation and physical protrusion of the disc can go on to cause pressure on the epidural venous plexus, causing venous obstruction.6 When the venous side backs up, it can lead to decreased perfusion of the nerve root from the arterial side. Prolonged irritation and poor blood circulation appear to make these nerve roots hypersensitive,7 further contributing to prolonged radicular pain.

Figure 2-10 Right-sided disc herniation, affecting only the ipsilateral nerve root. In this case the patient would have only right leg symptoms with the left leg being unaffected. |

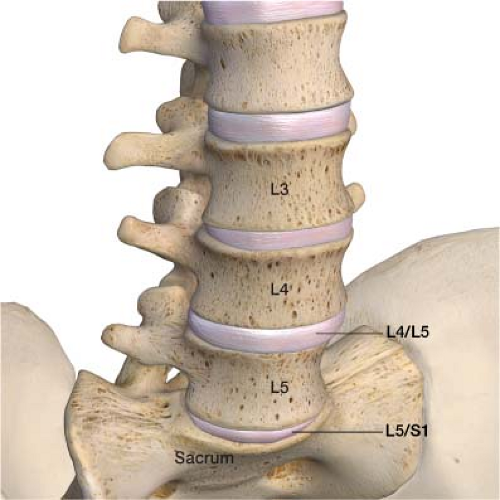

Figure 2-11 The L4/L5 and L5–S1 disc level. Ninety percent of, lumbar disc herniations occur at these two levels. |

Ninety percent of lumbar disc herniations occur between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebral bodies (L4–L5) and between the fifth lumbar vertebral body and the sacrum (L5–S1) (Fig. 2-11). This is a matter of physics. The greatest range of motion in the spine is at the L4–L5 and L5–S1 levels, which makes these discs most vulnerable to herniation. The irritation of a specific nerve root or roots by these discs sends a signal to the brain, which interprets this as pain along the entire nerve. For example, irritation of the L5 nerve root tricks the brain, which senses that the entire nerve, not just the nerve root, is affected.

History and Examination

On history, patients often report their radicular pain as being burning, electric, sharp, and lancinating. The symptoms can be constant or come and go. It is possible to make the pain worse by leaning forward, because this position may put more pressure on the nerve root by further herniating the disc against the nerve root. On examination, the course that the pain travels helps identify which nerve root is affected (Fig. 2-12). The

longitudinal extent of the pain appears to be proportional to the amount of pressure exerted on the nerve root,7 thus the further down toward the toes the pain spreads along the nerve root, the more affected it is. Motor testing also helps identify which nerve root may be the source of the problem. If there is weakness in quadriceps strength, it indicates that the L4 nerve root may be affected. Weakness on dorsiflexion indicates that the L5 nerve root may be affected, whereas plantar flexion weakness is indicative of an S1 radiculopathy (Fig. 2-13). A good way to help remember these is as follows. “Quad” means four—L4. Bending five toes toward the patient (dorsiflexion) tests L5. Pressing down on the gas (plantar flexion) of a new S1 Porsche tests S1. A positive straight-leg test is a nonspecific sign for lumbar disc herniation. The patient experiences pain in the back when the leg is extended. Normally, patients can elevate the leg 60 to

90 degrees on this test, which is positive if an elevation of 40 degrees or less produces pain (Fig. 2-14).

longitudinal extent of the pain appears to be proportional to the amount of pressure exerted on the nerve root,7 thus the further down toward the toes the pain spreads along the nerve root, the more affected it is. Motor testing also helps identify which nerve root may be the source of the problem. If there is weakness in quadriceps strength, it indicates that the L4 nerve root may be affected. Weakness on dorsiflexion indicates that the L5 nerve root may be affected, whereas plantar flexion weakness is indicative of an S1 radiculopathy (Fig. 2-13). A good way to help remember these is as follows. “Quad” means four—L4. Bending five toes toward the patient (dorsiflexion) tests L5. Pressing down on the gas (plantar flexion) of a new S1 Porsche tests S1. A positive straight-leg test is a nonspecific sign for lumbar disc herniation. The patient experiences pain in the back when the leg is extended. Normally, patients can elevate the leg 60 to

90 degrees on this test, which is positive if an elevation of 40 degrees or less produces pain (Fig. 2-14).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree