Nephrotic and Nephritic Renal Disease

Hillary Wall Pharm.D.

Joseph A. Grillo Pharm.D.

Eva Fischer M.D.

Glomerular disease is the third largest cause of chronic renal insufficiency in the United States. The U.S. Renal Data System estimates that 12.6% of cases of end-stage renal failure are the result of glomerular nephritis (National Institute of Diabetes, 1994). Glomerular diseases are similar in that they are all related to abnormalities within the glomerulus. However, the glomerulopathies comprise a somewhat diverse group of disorders in terms of prevention, presentation, prognosis, and treatment (Glassock et al, 1995; Adler et al, 1995; Glassock & Cohen, 1996). Although glomerular diseases often ultimately require renal biopsy for diagnosis, careful evaluation of a patient’s history, physical exam, urinalysis, and age may allow the provider to narrow the diagnosis significantly. This chapter is intended to give an overview of glomerular disease. Patient referral to a specialist in nephrology would be prudent.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

A comprehensive review of the anatomy and physiology of the kidney are discussed in the chapters on chronic and acute renal disease (Chaps. 30 and 31).

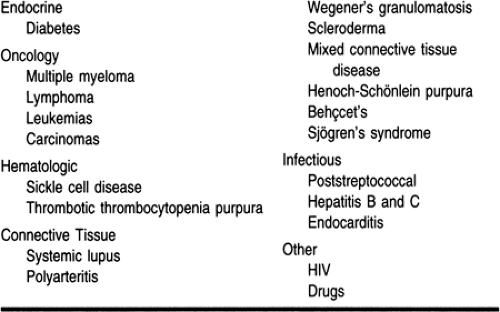

The glomerulopathies are often confusing in that they may be grouped according to their histology, cause, presentation, type of urinary sediment, or some combination of all of the above (Glassock, 1991; Shayman, 1995). Glomerulopathies are categorized as primary or secondary. Primary glomerulopathies originate in the glomeruli of the kidney. Secondary glomerulopathies are a consequence or complication of a systemic disease (Table 32-1). The strong association of primary glomerulopathies with certain diseases suggest that some are in fact systemic diseases that are limited to the kidney. Histologically, the patterns observed in the kidney cannot be differentiated based on primary or secondary glomerulopathies (Glassock, 1991). Glomerular disease may also be divided into a nephrotic or nephritic (ie, focal or diffuse) category based primarily on urinary findings. Some of the more common causes (both primary and secondary) of nephrotic and nephritic glomerular disease will be discussed.

Nephrotic Diseases

MINIMAL CHANGE DISEASE (NIL DISEASE)

Minimal change disease accounts for about 15% to 25% of all cases of glomerulonephritis seen in adults (Pontcelli & Patrizia, 1994). Light microscopy reveals normal or minimal (hence the name) changes in the mesangial cell proliferation. Most of the cases are idiopathic in origin. Some occurrences are attributed to drugs, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (in particular fenoprofen), lithium, tiopronin, ampicillin, rifampin, and interferon (Glassock & Cohen, 1996; Glassock, 1991). Malignancy, in particular Hodgkin’s lymphoma, has also been associated with minimal change disease (Meyrier et al, 1992). The tumor is thought to produce cytokines that are lethal to the glomerular epithelial cells. Secondary minimal change disease responds well to removal of the cause or treatment of the underlying disease.

Usually patients with minimal change disease present with edema and proteinuria in the nephrotic range. Many patients improve with corticosteroids; other therapies have also been tried (Pontcelli & Passerini, 1994; Fujimoto et al, 1991; Glassock, 1993). Overall, the prognosis for patients with minimal change disease is good. Progression to end-stage renal disease is unusual (Nalasco et al, 1986).

MEMBRANOUS GLOMERULONEPHRITIS (OR NEPHROPATHY)

Membranous nephropathy is the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults. The majority of the cases diagnosed are idiopathic, although cases associated with hepatitis B infections, malignancy, systemic lupus erythematosus, and drugs (penicillamine and gold) have been reported (Glassock et al, 1995; Glassock, 1991; Pontcelli & Patrizia, 1994). Membranous nephropathy is more prevalent in patients in their 40s and 50s. Clinically, most patients present with edema and nephrotic-range proteinuria. Hematuria is seen in about half of the patients. Hypertension is noted in less than 40% of the patients. Increased plasma creatinine concentrations are seen in patients with advanced disease, and these patients are more likely to have hypertension (Glassock et al, 1995; Glassock & Cohen, 1996; Pontcelli & Passerini, 1994).

The natural history of membranous nephropathy is variable. Some reports estimate that as many as half the patients presenting with nephrotic syndrome will develop end-stage renal disease within 10 years from diagnosis (Pontcelli & Patrizia, 1994). Other patients have a very benign course, with spontaneous remissions. As with most of the glomerulopathies, long-term studies on outcome and progression to renal disease are limited. The variability in the natural course of the disease makes the evaluation and selection of therapy quite difficult and controversial (Schieppati et al, 1993; Hebert, 1995; Imperiale et al, 1995; Piccoli et al, 1994; Remuzzi et al, 1994). Factors that are associated with increased risk of progression to end-stage renal disease include male gender, age greater than 50 years, heavy proteinuria, abnormal plasma creatinine concentrations, interstitial fibrosis on biopsy, and hypertension (Glassock et al, 1995; Glassock & Cohen, 1996; Schieppati et al, 1993; Hebert, 1995; Imperiale et al, 1995; Piccoli et al, 1994; Remuzzi et al, 1994).

FOCAL SEGMENTAL GLOMERULOSCLEROSIS

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is notable for scarring or sclerosing of the glomeruli. “Focal” refers to the fact that not all the glomeruli are involved. It is more common in young adults less than 40 years of age. It is one of the primary glomerulopathies, so the majority of the cases are thought to be idiopathic. However, as is typical, systemic disease is associated with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, most notably HIV disease. HIV nephropathy appears to produce a more rapid deterioration of renal function than focal segmental glomerulosclerosis from idiopathic causes (Glassock & Cohen, 1996; Glassock, 1991; Pontcelli & Passerini, 1994).

Patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis usually present with proteinuria in the nephrotic range, impaired renal function, and hypertension; red cells and red cell casts can be observed in the urine sediment. Many patients progress to end-stage renal disease. Some think that focal segmental glomerulosclerosis may be a degenerative change from minimal change disease (Glassock & Cohen, 1996).

DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY (DIFFUSE AND NODULAR GLOMERULOSCLEROSIS)

Diabetic nephropathy causes renal failure in almost a third of patients with type I diabetes and about 5% of type II patients (Perneger et al, 1994). Diabetic glomerular disease is the most common cause of end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis (Markett & Freidman, 1992). Diabetic nephropathy is described as a diffuse and nodular glomerulosclerosis. Diffuse thickening in the glomerular basement membrane is observed with the light or electron microscope in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Kimmelstiel-Wilson lesions are nodules that can be seen in more advanced stages of diabetic renal disease (Glassock, 1991). The exact mechanism of diabetes glomerular disease is not clearly understood. One theory is that advanced glycosylation end products (produced by the glycosylation of proteins) accumulate and alter the mesangial matrix (Makita et al, 1991). Persons with diabetes are noted to have an increase in glomerular filtration (hyperfiltration) before they develop microalbuminuria. This hyperfiltration may be damaging to the glomerulus (Rudbert et al, 1992). Additionally, increased glucose concentrations may contribute to increased pressures within the glomerulus, which are detrimental (Glassock, 1991).

Clinically, patients with diabetic nephropathy may initially present with microalbuminuria (not detectable on the routine urine protein dipstick), then proteinuria, which can be in the nephrotic range. In patients with type I diabetes, progression to end-stage renal disease occurs 15 to 20 years after the onset of microalbuminuria.

AMYLOIDOSIS

Patients with renal amyloidosis usually present with severe proteinuria, severe edema, and low albumin concentrations. Patients may also present with hepatosplenomegaly, congestive heart failure, and carpal tunnel syndrome. The plasma creatinine concentration may be normal or moderately elevated. Amyloidosis can be primary or secondary. Secondary disease is usually associated with multiple myeloma, tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, infection, or chronic inflammation. The majority of patients have primary amyloidosis. Primary amyloidosis is usually seen in adults older than 40 years. The prognosis and treatment options for primary amyloidosis are limited. Treatment of the cause of secondary amyloidosis (eg, infection) may lead to resolution of the amyloidosis and as such a more favorable outcome (Adler et al, 1995; Glassock, 1991).

Nephritic Glomerular Diseases

IgA (BERGER’S)

IgA, or Berger’s disease, is the most common glomerulopathy. Granular IgA deposits observed under immunofluorescence are diagnostic for Berger’s disease (Glassock et al, 1995; Glassock & Cohen, 1996; Glassock, 1991). Approximately half of the patients with IgA nephropathy have high plasma IgA concentrations. IgA typically presents with intermittent gross hematuria and flank pain. Often the diagnosis is made when mild proteinuria and microscopic hematuria are noted on a urinalysis. IgA has been observed to present about 5 days after the onset of an upper respiratory tract infection. The majority of cases of IgA are thought to be idiopathic; other causes include cirrhosis, gluten enteropathy, nil disease, oat cell carcinoma, disseminated tuberculosis, and HIV infection (Galla, 1995). IgA is considered to have a better outcome than some of the other glomerulopathies, although end-stage renal disease may develop in 20% of patients within 20 years of diagnosis. Factors that have been suggested to increase the chance of developing end-stage renal disease are increased in plasma creatinine concentration, hypertension, urinary protein excretion greater than 1 g/day, or morphologically glomerular scarring, crescent formation, or tubulointerstitial changes. The natural history of IgA is generally favorable, taking 10 to 20 years to develop into end-stage renal disease, if it occurs (Glassock et al, 1995; Glassock, 1991; Galla, 1995).

HEREDITARY NEPHRITIS

Hereditary nephritis, or Alport’s syndrome, is an X-linked disorder associated with hearing loss and lenticular opacities. Men generally progress to end-stage renal disease; women tend to have a more benign course. Histologically, thinning of the glomerular basement membrane is observed early in the disease course. Later, splitting or laminating of the basement membrane

is more diagnostic of Alport’s syndrome. Asymptomatic hematuria and proteinuria or gross intermittent hematuria is the typical early presentation. Family history of deafness would favor the diagnosis of Alport’s over IgA nephropathy; the presentation of the disease may be quite similar in other respects (Glassock et al, 1995; Glassock & Cohen, 1996; Glassock, 1991; Bodziak, 1994).

is more diagnostic of Alport’s syndrome. Asymptomatic hematuria and proteinuria or gross intermittent hematuria is the typical early presentation. Family history of deafness would favor the diagnosis of Alport’s over IgA nephropathy; the presentation of the disease may be quite similar in other respects (Glassock et al, 1995; Glassock & Cohen, 1996; Glassock, 1991; Bodziak, 1994).

POSTINFECTIOUS GLOMERULONEPHRITIS

A proliferative type of glomerulonephritis can be observed as a complication of infection, particularly of the throat and skin. Most cases involve only mild renal disease that may not even be identified. The most common infections associated with postinfectious glomerulonephritis are certain strains of streptococci. Clinically, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis presents 1 to 3 weeks after pharyngitis or impetigo infections, respectively (Glassock, 1991). Patients may present with severe hematuria, bilateral flank pain, a decrease in glomerular filtration rate, and oliguria. Nephritic urine sediment is typical, although white blood cells may be observed. The majority of patients have low plasma C3 concentrations, whereas antistreptolysin O values are elevated. Spontaneous resolution occurs in most patients, although some patients develop acute renal failure. Endocarditis is also associated with postinfectious glomerulonephritis (Adler et al, 1995; Glassock, 1991; Montseny et al, 1995).

RAPIDLY PROGRESSING GLOMERULONEPHRITIS

Rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis is the clinical presentation of a disorder noted for red blood cells of variable size and shape, proteinuria (usually not in the nephrotic range), and rapid deterioration in renal function. Untreated, it may progress to end-stage renal disease within months. Renal insufficiency tends to be severe because pathologically, rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis is associated with crescent formation in almost all the glomeruli. Crescent formation is not diagnostic, however; it can occur in almost any type of proliferative glomerulonephritis. Thus, the term “crescentic glomerulonephritis” should not be used as a synonym for rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis (Glassock et al, 1995; Glassock & Cohen, 1996). Rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis is the result of primary and secondary causes. The primary causes are classified as types I to V. In type I, also known as antiglomerular basement membrane antibody disease, antibodies are directed against antigens in the glomerular basement membrane. These patients have antibodies that can be detected in the serum. Secondary causes are often grouped into infectious (endocarditis, hepatitis), systemic (lupus, malignancy), or drug-related (allopurinol, hydralazine), and as complications of other primary glomerulopathies (membranous nephropathy, IgA nephropathy) (Glassock,; Merkel et al, 1994). Treatment depends on the cause and if primary the particular subtype (Glassock et al, 1995; Adler et al, 1995; Glassock & Cohen, 1996; Glassock,).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree