TOPICS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Obesity is a growing epidemic in the United States and throughout the developed world. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), only 13% of Americans were considered obese in 1962. This number significantly increased to 35% by 2013. Today, every state in the country has at least a 20% prevalence of obesity, with two states now over 35%.1 This trend extends to parturients, with over half of all pregnant patients being overweight and obese, and 8% reaching extreme obesity.2

Definition

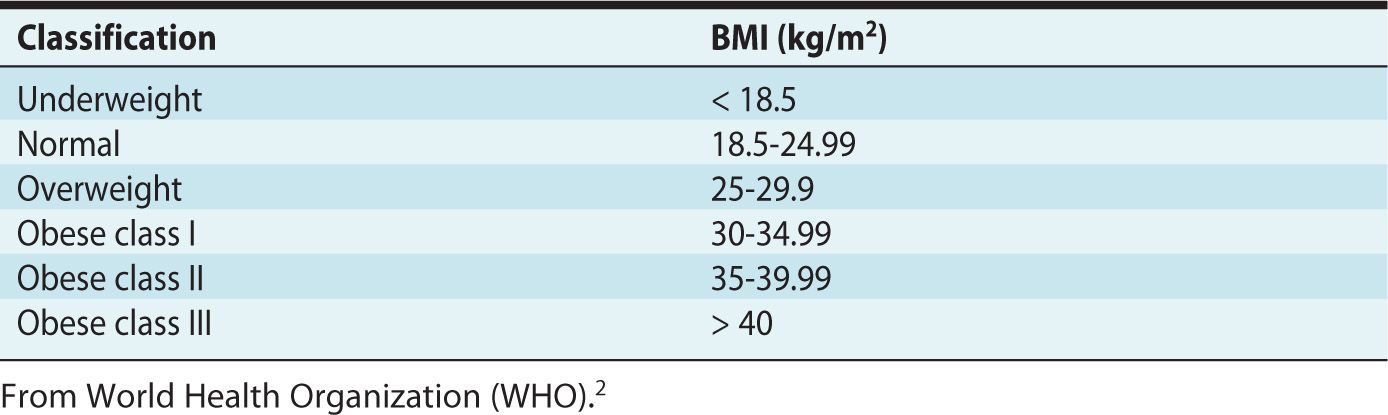

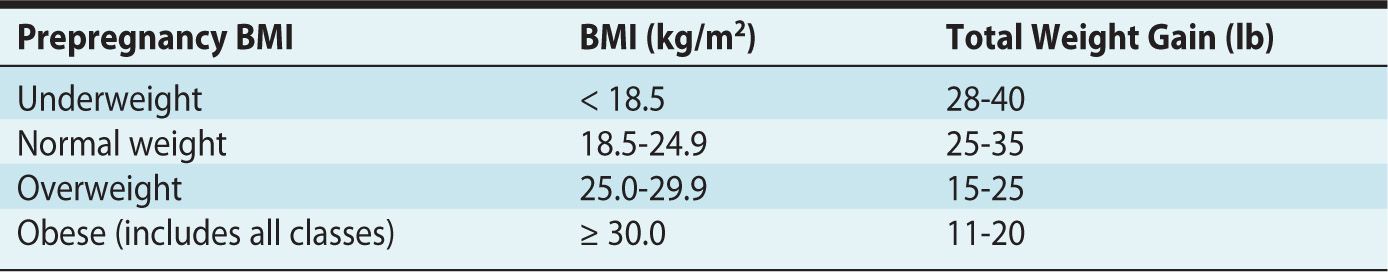

The classification of obesity has been standardized with the use of the body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), with a value of 30 or greater being considered obese. While the World Health Organization (WHO) has subdivided obesity into three classes (Table 27-1), the Institute of Medicine guidelines regarding gestational weight gain do not discriminate based on this classification (Table 27-2).3,4

Table 27-1. Body Mass Index (BMI) Classification System

Table 27-2. Institute of Medicine Recommendations for Total Weight Gain During Pregnancy, Based on Prepregnancy Body Mass Index (BMI)

ETIOLOGY

Obesity results from an imbalance of caloric intake and physical activity. While it is recommended to perform at least 30 minutes of exercise daily during pregnancy, most parturients do not meet this goal.5,6

Obesity is an independent risk factor for maternal and neonatal morbidity.7 Therefore, preconception counseling should occur for all obese women of childbearing age to 1) educate these patients about their risk and 2) enable weight reduction strategies to occur prior to pregnancy. When pregnancy occurs, patients should be educated about the effects of obesity on the course of pregnancy, labor and delivery.2 Nutritional consultation and exercise goals should be established early and evaluated throughout pregnancy. Despite adequate consultation, only 19% of obese parturients believe their weight affects pregnancy risk.

EFFECTS OF OBESITY ON THE FETUS

Maternal obesity, has been implicated as a risk factor for structural defects in the fetus, including congenital heart defects, facial clefting, hydrocephalus, limb reduction and most commonly neural tube defects.9

These congenital anomalies may be poorly visualized during prenatal ultrasound due to decreased image resolution and quality related to abdominal wall adiposity. For this reason, it is advised to delay evaluation of fetal anatomy until after the 18th week of pregnancy.7

The incidence of intrauterine fetal demise and stillbirth is increased more than two-fold in obese parturients.10 Although the exact etiology is unclear, placental insufficiency secondary to associated maternal comorbidities may play a role.

Both preterm delivery (possibly due to maternal medical indications) and post-term deliveries are more prevalent. Offspring of obese mothers are more likely to be large for gestational age (LGA) and to suffer from childhood obesity.9,11,12,13.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

During pregnancy, physiologic changes occur that affect nearly every organ system. Obesity can exacerbate these altered states, increasing the risk to both mother and fetus. The 2006-2008 data collected by the Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CEMACE) reported that 49% of the maternal deaths occurred in women who were either overweight or obese. Seventy-eight percent of mothers who died from thromboembolism and 61% of mothers who died from cardiac disease were overweight or obese.14

Cardiovascular

During normal pregnancy, there is an increase in cardiac output which peaks immediately postpartum. Obesity further increases cardiac output by 30 to 50 mL/min for every 100-g increase in adipose tissue weight, which leads to a relative increase in heart rate, decreased diastolic interval, and resultant diastolic dysfunction.15 Plasma volume expansion is increased further with obesity, which results in further left ventricular hypertrophy.

The decrease in systemic vascular resistance is attenuated as a result of increased levels of plasma leptin, insulin, and inflammatory mediators resulting in an increase in sympathetic activity.16 This pressure overload may result in dilation of the myocardium and systolic dysfunction.

Obese parturients are more likely to enter pregnancy with chronic hypertension. Furthermore, endothelial dysfunction from an elevation in C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α leads to an increased incidence of pregnancy-induced hypertension in obese parturients, with over two times the risk for class I obesity and triple the risk for class II obese parturients. The incidence of preeclampsia is 10% to 25% greater in the obese than the nonobese, with a two-fold increase in risk for every 5- to 7-unit increase in BMI.17

Respiratory

The plasma expansion of pregnancy results in capillary engorgement of the upper airway and resultant tissue edema and friability. Obesity compounds these changes with relative increase in tissue mass, neck circumference, and enlarged breasts, making airway management especially challenging in the obese parturient.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is often underdiagnosed in pregnancy. Hormonal changes lead to an increased sensitivity of the respiratory center to apneic episodes that in theory should decrease the incidence of OSA. However, this condition may lead to pulmonary hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia and should be addressed.18

There is a decrease in parturients’ functional residual capacity (FRC) due to diaphragmatic elevation from the enlarging uterus and increased chest wall resistance. Although some studies show an improvement in FRC when obese women become pregnant, these results were obtained from women in the sitting position. However, the effects of a general anesthetic in obese women in the supine position are unknown. Furthermore, FRC may fall below closing capacity in obese parturients, leading to shunting. Oxygen consumption increases with increasing weight, as does the work of breathing proportionally related to the degree of obesity.

Gastrointestinal

Decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone and increased intragastric pressure are normal physiologic changes seen during pregnancy that place parturients at an increased risk for aspiration. Although studies have shown no decrease in gastric emptying in nonlaboring patients that are either of normal weight or obese, one should still be concerned for aspiration due to the decreased barrier pressure and the increased incidence of hiatal hernia observed in obese parturients.17

Furthermore, patients may become pregnant following bariatric surgery. Decrease in the rates of diabetes, hypertensive disorders, OSA, and fetal macrosomia are benefits; however, serious complications can occur. Band slippage, gastrointestinal bleeding, internal intestinal herniation, and maternal death have all been reported. For this reason, ACOG recommends that a bariatric surgeon jointly monitor postbariatric surgery patients during their pregnancy. Vitamin supplementation may be required for patients who have undergone procedures causing a malabsorption syndrome, and, in others, adjustment of lap bands may be required to allow for adequate maternal weight gain.2,19 Early anesthetic consultation is advised, and potential gastrointestinal obstruction or severe reflux disease should be considered when developing an anesthetic plan.

Metabolic

Obese parturients have a greater risk of beginning pregnancy with diabetes mellitus and of developing gestational diabetes during pregnancy. Patients with a history of previous gestational diabetes mellitus, macrosomia, or a family history of diabetes should be considered to be at risk. Screening for diabetes should be undertaken early in the first trimester for obese parturients and may be repeated as necessary. Although gestational diabetes mellitus is observed in 1% to 3% of normal weight parturients, 17% of obese parturients will develop the condition.17 Gastroparesis due to autonomic dysfunction may complicate obesity, leading to a decrease in gastric emptying and therefore increased risk of aspiration.

MANAGEMENT AND ANESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS

Obstetric Complications: Peripartum

The serum concentration of leptin, an oxytocin antagonist, is elevated in obese parturients and may be implicated in the higher rate of postdates pregnancy, dysfunctional labor, and slower cervical dilation observed in the obese population as compared to normal-weight parturients. Thus, obese parturients have a greater risk of requiring induction of labor and augmentation with oxytocin. Early amniotomy is also performed more frequently in these patients.

Maternal obesity is an independent risk factor for fetal macrosomia. When these patients do succeed at vaginal delivery, the risk of shoulder dystocia is increased by more than a factor of three as compared to nonobese women, and maneuvers to deliver the infant are less successful. Instrumented vaginal delivery, including the use of forceps and vacuum, occurs in 17.3% of obese women versus 8.4% in nonobese parturients. The incidence of third-degree and fourth-degree tears is also greater.17

Induction of labor is more likely to fail and progress to cesarean delivery in obese parturients (14.9% versus 7.9%).17 Risk of progressing to cesarean delivery may be greatest during the first stage of labor.20 Potential factors include primary uterine inertia and inadequate uterine contractions, cephalopelvic disproportion from soft tissue dystocia and fetal macrosomia, and challenging fetal heart rate and contraction monitoring due to technical difficulties in monitoring. Obese parturients are also twice more likely to fail at vaginal birth after cesarean when compared to normal-weight parturients.17

The rate of cesarean delivery is increased two to four times in obese women proportional to BMI. If the accepted ACOG rate of cesarean delivery is 20.7% in parturients of normal weight, it increases to 33.8% in class I obese women and 47.4% in class II obese women.2 Many factors contribute to the increased risk of cesarean delivery, including higher rates of failed labor, inaccurate estimations of fetal weight by prenatal ultrasound, emergency cesarean section from complications related to diabetes or hypertensive disorders, and prior cesarean deliveries.

Obesity is an independent risk factor for uterine atony and postpartum hemorrhage. Abdominal wall adiposity can make surgery more challenging and operative times longer.21 Adequate surgical exposure often requires retraction of the panniculus, which may lead to cardiorespiratory compromise.

Anesthetic Considerations

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

A mere 13% of obstetricians routinely discuss the additional anesthetic risks of obesity with their patients.22 To best educate patients and coordinate plans for their delivery, ACOG encourages early anesthesiology consultation for all obese parturients, prior to delivery if possible, but definitely on arrival on the labor floor for those who have not received earlier evaluation.2 A comprehensive assessment of end-organ function and comorbidities is essential. There should be a multidisciplinary plan for not only labor but also for cesarean delivery and postpartum care. Risks of complications from anesthesia and logistics of the delivery should be discussed. Education may be presented in a clinic visit with an anesthesiologist or another anesthesia provider, along with videos, pamphlets, or other media.

ANALGESIA FOR LABOR AND VAGINAL DELIVERY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree