The absolute number of accidental deaths is greatest in people aged 65 years and over. In this age group, more than half of all fatal trauma results from falls. However, for most of the population, road traffic is the greatest danger, being responsible for about 40% of trauma deaths and seriously injuring somebody every 20 minutes in the UK. Falls from a height and motor vehicle accidents commonly lead to multiple injuries (‘polytrauma’).

Alcohol is a significant factor in about one in seven of all fatal car crashes and in over 40% of deaths from falls. (For further information on alcohol and injury → p. 374.)

Speed also kills. A car hitting 100 pedestrians:

| at 20 mph |  | kills 5 |

| at 30 mph |  | kills 45 |

| at 50 mph |  | kills 85 |

Deaths from trauma were commonly said to occur in a triphasic distribution:

However, in the UK, most fatalities (around 80%) actually occur at the scene of the injury and later deaths do not neatly fit into this classification. Prevention is thus the best way to reduce the effect of injury, next is protection to mitigate its impact and finally there must be timely and effective treatment.

TRAUMA CARE

The Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) system, developed by the American College of Surgeons in the late 1970s, has become the standard method for initial assessment and management of trauma victims. There are three main phases:

Preparation for Reception of Trauma Victims

If warned of the imminent arrival of patients who are multiply injured:

- Assemble a team in the resuscitation area

- Warn appropriate in-patient specialties

- Allocate tasks: doctor/nurse to airway and breathing, doctor/nurse to circulation, nurse to record findings and interventions, nurse to support relatives, senior doctor as team leader

- Check equipment and put on protective clothing

- Meet the ambulance with doctor/nurse to ensure continuous care of the airway

- Detain the ambulance crew for a subsequent report on the biomechanics of impact (Box 2.1), initial clinical state and prehospital care

Box 2.1 Factors Associated with Severe Injury

Box 2.1 Factors Associated with Severe Injury- impact at high speed

- fatality of other passenger(s)

- ejection from vehicle

- pedestrian struck by vehicle

- motorcyclist with no crash helmet

- steering wheel or windscreen damage

- significant intrusion into passenger compartment

The Primary Survey and Resuscitation Phase (Initial Assessment and Management)

- Assess and secure the airway while guarding the neck. Manual in-line stabilisation may be needed.

- Give high-flow 100% oxygen.

- Protect the neck with a rigid cervical collar and a head holder (or sandbags and tape).

- Assess the breathing; exclude/treat tension pneumothorax and other critical chest injuries. Cover ‘sucking’ chest wounds with a flap dressing:

- stop external bleeding by direct pressure and establish venous access at two sites – large cannulae in large veins

- take 20 mL blood for cross-matching, a coagulation screen and baseline glucose, electrolytes and haemoglobin

- commence infusions of 0.9% saline and then colloid (a 50 : 50 ratio of the two is probably a good start).

- stop external bleeding by direct pressure and establish venous access at two sites – large cannulae in large veins

- Take and record the pulse, BP and respiratory rate. Attach the patient to a pulse oximeter and a cardiac monitor.

- Determine the level of consciousness (AVPU → p. 7) and the size and reactivity of the pupils.

- Assess limb movements to confirm spinal cord integrity.

- Remove remaining clothing and expose the patient to allow further assessment.

- Measure the blood glucose with a reagent stick in all unresponsive patients.

- Obtain brief details of the patient and the trauma that he or she has suffered (AMPLE → p. 12).

- Consider early analgesia.

- Request the three major radiographs of trauma: chest, lateral cervical spine and pelvis.

The Secondary Survey (Further Assessment)

- When resuscitation is successfully under way, begin a head-to-toe examination. If any features in the primary survey are still giving cause for concern, return to the assessment of oxygenation and circulation.

- When the front of the trunk and the limbs have been assessed, call for help to log-roll the patient. Four people are required, one controlling the head alone and taking charge of the timing of the turn.

- When rolled, examine the thoracolumbar spine, listen to lung fields, examine the perineum and do a rectal examination. The last will reveal the anal tone, presence of perineal injuries, position of the prostate and any blood.

- Document the injuries discovered.

- Consider the priorities for investigation and treatment. Discuss the patient with doctors from other specialties who should, by now, have arrived in the resuscitation room.

- Maintain contemporary notes and repeat the ABCs and baseline observations frequently.

The Chain of Care

Prehospital

In urban areas, with short transfer times to a definitive care centre and no delay involved in releasing the injured patient, a ‘scoop and run’ prehospital policy is best. Pause only to secure the airway and protect the neck. In other situations (e.g. entrapment or prolonged transfer time) field resuscitation may be helpful (Box 2.2). Try to treat in transit; don’t delay and play!

Box 2.2 Prehospital Management

Box 2.2 Prehospital Management- Secure the airway – jaw thrust, oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway. Consider intubation

- Protect the cervical spine – collar and head holder

- Ensure adequate ventilation and oxygenation (this may necessitate decompression of the chest: → p. 74)

- Cover open chest wounds

- Control external haemorrhage by direct pressure

- Start intravenous (IV) infusions only if this does not delay transfer

- Protect thoracic and lumbar spine – backboard or ‘scoop’ stretcher

- Provide analgesia

- Record initial assessment of cardiorespiratory and neurological status

- Communicate with the hospital – assessment, management and expected time of arrival

Emergency Department

The primary concerns here are:

This can be achieved by a well-rehearsed team working to agreed protocols and integrated into a comprehensive trauma care system.

PRIMARY SURVEY AND RESUSCITATION

This must be carried out in a strict order of priority. Problems are corrected as they are identified. The ATLS formula for the primary survey is:

Airway

Check for responsiveness.

Then look for the following:

- No movement of air (complete airway obstruction or apnoea)

- Noises from the upper airway (partial airway obstruction); there may be snoring, rattles, stridor or other sounds

Box 2.3 Causes of Upper Airway Obstruction in Trauma

Box 2.3 Causes of Upper Airway Obstruction in TraumaAny injury severe enough to compromise the airway may also have damaged the cervical spine.

TX

All severely injured patients require a high inspired oxygen concentration. The airway must be:

- cleared of foreign material with suction, Magill’s forceps and fingers, if necessary

- maintained using a jaw-thrust manoeuvre, a Guedel oropharyngeal airway, a nasopharyngeal airway or by endotracheal intubation (the nasopharyngeal airway is safe and well tolerated in the conscious patient and is much less likely to stimulate gagging than the Guedel airway)

- protected by vigilance, suctioning and positioning.

When traumatic disruption of the facial or laryngeal structures prevents intubation, surgical access to the airway must be obtained. Emergency tracheostomy is difficult and dangerous and has been superseded by the technique of cricothyroidotomy. Needle puncture of the cricothyroid membrane is preferable in children aged <12 years (→ Box 2.4).

Box 2.4 Artificial Airways in Trauma

Box 2.4 Artificial Airways in Trauma Box 2.5 Cricothyroidotomy

Box 2.5 Cricothyroidotomy- Extend the patient’s neck while controlling the head

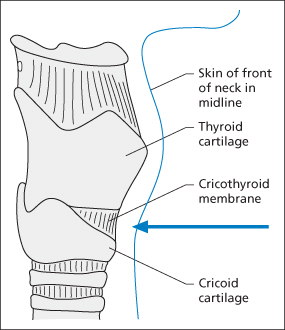

- Mark the skin over the centre of the cricothyroid membrane (which lies between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages → Figure 2.1)

- Support the larynx and tighten the overlying skin with the non-dominant hand

- Make a small transverse incision through the skin and spread the edges outwards

- Make a transverse incision through the cricothyroid membrane and open the wound with the handle of the scalpel

- Insert an appropriate size of endotracheal or tracheostomy tube

- Start ventilation and check for air entry

- Secure the tube

Box 2.6 Needle Cricothyroid Puncture

Box 2.6 Needle Cricothyroid Puncture- Extend the patient’s neck while controlling the head

- Mark the skin over the centre of the cricothyroid membrane (which lies between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages → Figure 2.1)

- Attach a cannula and needle of an appropriate size (at least 12 G for an adult) to a small syringe

- Support the larynx and tighten the overlying skin with the non-dominant hand

- Puncture the skin and cricothyroid membrane with the needle, aiming for the small of the back, aspirating as the needle is advanced

- When air is easily aspirated, advance the cannula and withdraw the needle

- Recheck the ease of aspiration of air (it is surprisingly easy to miss the trachea with a needle, especially in children)

- Attach the cannula to either the wall or the flow-meter oxygen supply via an in-line Y-connector. In a child, start with a flow meter set at a delivery rate in litres equal to the child’s age in years

- Adjust the flow rate and inspiratory time until adequate chest movement is achieved. Expiration may take several seconds

- Secure the cannula

The Cervical Spine

Neck injury must be assumed to have occurred in all patients who have sustained polytrauma until excluded by clinical examination and good quality imaging. Patients at particular risk include those who have sustained:

- any injury above the clavicle

- head injury associated with depressed consciousness

- a high-speed injury

- a fall from a height.

A normal neurological examination does not exclude cervical spine injury. Moreover, conscious patients with other painful injuries may not always complain of neck discomfort.

TX

The neck must be splinted to prevent damage to the spinal cord from the movement of an unstable injured spine. This should be achieved with a well-fitting hard collar and a purpose-built head holder. However, if the patient is struggling violently, attempts to control the head may inadvertently lead to further injury. In these circumstances, it is better to use a collar alone. The cause of the agitation should be sought. It is often hypoxia, pain or both. In a patient with a depressed level of consciousness, a full bladder may be responsible.

Breathing

Look for

- External signs of injury

- Abnormal respiratory rate or pattern

- Unequal chest movement

- Tracheal shift and displacement of the apex beat

- Decreased breath sounds

- Increased or decreased resonance

- Low SaO2 (arterial O2 saturation)

- Signs of hypoxia (tachycardia, agitation or confusion and cyanosis).

Five major chest injuries require immediate recognition and treatment during the primary survey:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree