Precipitant Delivery

In the UK, most pregnant women have planned maternity care and so have made clear arrangements for the delivery of their baby. However, occasionally women arrive at the emergency department (ED) in the second stage of labour (i.e. after the cervix is fully dilated). Delivery of the baby may be imminent and assistance must be given (→ Boxes 17.1 and 17.2 and Figure 17.2).

Box 17.1 Precipitant Delivery

Box 17.1 Precipitant Delivery- Reassure the patient and take her to a private room

- Summon help (midwife and paediatrician)

- Keep a record of timing throughout

- Request a delivery pack, turn on the neonatal resuscitation trolley heater and get the Entonox apparatus

- Try to ascertain the gestational age of the baby and, briefly, the obstetric history of the mother

- Examine the abdomen to discover the position and number of babies

- Listen to the fetal heart with a Pinnard (or an electronic) fetal stethoscope. The rate should be >120 and if it slows with contractions it should recover quickly

- Allow the patient to adopt any position that she chooses

- Administer Entonox if required

- If liquor is draining, check the colour. Meconium staining indicates fetal distress

- Perform a vaginal examination to assess progress in labour, but NOT if there has been any bleeding (because of the risk of placenta praevia). If the cord is prolapsing, push it back into the cervix and hold it there until help arrives. Try to prevent cord compression by the head of the baby

- If the patient is ‘pushing’ (i.e. is late in the second stage) look to see if the fetal head, or other presenting part, is visible at the vulva. If it is, put on gown and gloves from the pack and place sterile towels around the delivery area. Cleanse the vulval area

- Control the descent of the head with the left hand while the right hand supports the perineum with a sterile pad

- As the head is delivered, encourage the mother to push more gently, while keeping the head flexed. If a breech appears, support the body gently without traction

- Check for the cord around the baby’s neck and free it if necessary

- Allow the baby’s head to turn laterally as the shoulders rotate. With the next contraction the body will be expelled. Deliver it by lifting the baby up and on to the mother’s abdomen

- Tie or clamp the cord in two places at least 10 cm from the umbilicus and cut between the ties

- For resuscitation of the baby → Box 17.2

- Await spontaneous delivery of the afterbirth

- Keep the mother warm. If there is excessive bleeding, establish an IV infusion and give an ampoule of an oxytocic (e.g. Syntometrine 1 mL or ergometrine 0.5 mg IM)

Box 17.2 Resuscitation of the Newborn

Box 17.2 Resuscitation of the Newborn- warmth and peripheral stimulation

- gentle pharyngeal suctioning

- inflation of the lungs with oxygen using a bag and mask

- pharyngeal suctioning (meconium in the mouth indicates the need for inspection of the larynx and, if necessary, tracheal suctioning)

- ventilation with oxygen

- intubation if there is a skilled operator present (clumsy attempts may result in vagal bradycardia and laryngospasm) [endotracheal (ET) tube size = 3 mm after 28 weeks’ gestation]

- cardiac compression if the heart rate is <60 beats/min (three compressions after each inflation with a compression rate of 120/min)

- adrenaline via the IV or intraosseus routes (the weight of a full-term neonate is usually about 3.5 kg and the dose of adrenaline = 10–30 mcg/kg)

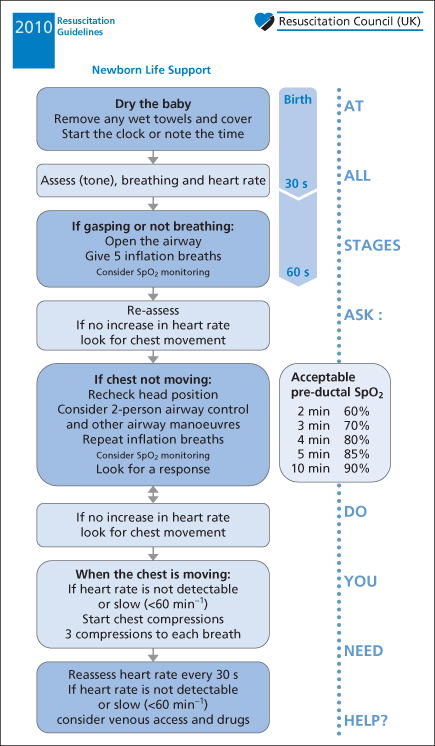

Figure 17.2 Resuscitation Council (UK) algorithm for life support of the newborn infant.

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Resuscitation Council (UK).

Antepartum Haemorrhage

This is vaginal bleeding occurring after 24 weeks’ gestation and is caused by placental abruption, placenta praevia or other less common lesions. The bleeding of placenta praevia is usually painless and starts around week 32 of gestation as the lower uterine segment is beginning to form. With abruption, severe blood loss and shock may occur in the absence of significant external bleeding (concealed haemorrhage). There may be pain and a hard, ‘wooden’ uterus.

TX

The patient requires IV fluids, cross-match of blood and immediate referral to the obstetric service.

Postpartum Haemorrhage

Bleeding may occur soon after delivery or later on in the puerperium. It is the later bleeds (secondary postpartum haemorrhage) that may present to the ED. The causes are retained products of conception and infection.

TX

IM Syntometrine (oxytocin 5 U and ergometrine 0.5 mg in 1 mL) may contract the uterus and control the bleeding. An IV infusion should be established and blood sent for cross-match before the patient is referred to the obstetrician.

Eclampsia

Eclampsia occurs in about 1 in 2000 deliveries in the UK and contributes to around 10% of maternal deaths. Women who are in late pregnancy or postpartum may occasionally present to an ED with eclamptic fits. The signs of pre-eclampsia (hypertension, oedema and proteinuria) may not be immediately apparent.

TX

- Summon senior anaesthetic and obstetric help.

- Manage the airway and breathing.

- Establish venous access.

- Control the fitting with standard therapy (e.g. IV lorazepam) followed by IV magnesium sulphate (→ below).

Magnesium Therapy:

Magnesium sulphate is now the standard treatment for the control of recurrent eclamptic seizures. An IV injection of 4 g is given over 5–10 min, followed by an IV infusion of 1 g/h for at least 24 h. If fits recur then a further 2 g is given intravenously over 5 min; this dose is increased to 4 g if the patient’s weight is >70 kg. (Note that 1 g magnesium sulphate is equivalent to approximately 4 mmol ionised magnesium.)

Major Trauma in Pregnancy

GYNAECOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Hyperemesis gravidarum is a severe form of morning sickness with intractable nausea and vomiting that prevents an adequate intake of food and drink. Around 75% of all pregnant women experience some degree of nausea and vomiting but hyperemesis occurs in only 0.5–2% of pregnancies and may affect the wellbeing of both the mother and the fetus. Weight loss, nutritional deficiencies and abnormalities in fluid and electrolyte and acid–base balance may occur. The peak incidence is at 8–12 weeks of pregnancy and symptoms usually resolve by week 20 in all but 10% of patients. Sufferers are more likely to be non-white and aged >30 years with a history of motion sickness, migraine or previous hyperemesis gravidarum. The condition is associated with multiple pregnancy, molar pregnancy and some fetal abnormalities; it may also have a genetic component. Strangely, cigarette smoking seems to be a protective factor! The cause of hyperemesis is unknown but is thought to be related to hormonal changes.

Investigations:

- Full blood count (FBC), C-reactive protein (CRP) and midstream specimen of urine (MSU) to exclude infection; routine blood chemistry

- Urine for ketones

- Ultrasound scan to assess fetal growth.

TX

Rehydration with IV fluids is usually required. Safe and effective antiemetics include IV metoclopramide, promethazine and ondansetron. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) has been found to be of help and avoidance of sensory triggers is important. Some women will require multiple admissions during their pregnancy.

Vaginal Bleeding in Pregnancy

Vaginal bleeding occurs in up to a fifth of all pregnant women but in over 50% of cases the pregnancy will continue successfully. After 24 weeks (and effectively after 20 weeks for the purposes of management in the ED) vaginal bleeding is classed as an antepartum haemorrhage (→ p. 316). Before this time it may be:

- a threatened abortion

- an incomplete abortion

- a complete abortion

- other (→ below).

Loss of the fetus is accompanied by:

- significant abdominal pain and tenderness

- heavy or continuing bleeding

- the passage of placental material in addition to blood clots

- an open cervical os

- the absence of a fetal heart on ultrasound examination.

Investigations:

Portable Doppler ultrasound scanners are useful only at gestations of >12 weeks, although formal scanning may detect a heart beat at 7 weeks’ gestation.

TX

Patients with the above features of imminent fetal loss require admission for observation. Severe bleeding necessitates IV fluids and, if fetal loss is assured, an oxytocic (e.g. Syntometrine 1 mL IM or oxytocin 5 U slowly IV). Pain must be relieved by appropriate analgesia, whatever the course of the pregnancy. Severe pain is sometimes caused by the passage of material through the cervix; great relief can be obtained by the removal of this tissue with sponge-holding forceps via a speculum.

Patients with threatened abortion without symptoms or signs of fetal loss may be referred back to the GP for bed rest at home, although requests for admission from patients must be given serious consideration. If possible, all such patients should be seen in a specialist pregnancy review clinic within 48 h. Early ultrasound scanning is essential.

The rhesus D antibody status of all patients with bleeding in pregnancy after 12 weeks’ gestation must be ascertained. It may be recorded on the obstetric cooperation card in later pregnancy. If antibody status is unknown, then blood should be sent for urgent grouping. Patients who are RhD negative with a gestation of 12 weeks or more must be protected from developing anti-D antibodies to fetal RhD-positive cells, which may have leaked into the maternal circulation. This is achieved by the administration of anti-D immunoglobulin to destroy any RhD-positive cells before they can sensitise the mother. To be effective, the γ-globulin must be given within 72 h of the onset of vaginal bleeding. The dose is 250 IU by deep IM injection for patients with a gestation of <20 weeks and 500 IU for those with a gestation of ≥20 weeks.

Ectopic Pregnancy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree