HIV/AIDS

Debra A. Kosko MN, FNP-C

Carla Alexander MD

Karen Benker MD

Valery Hughes BSN, RN

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is an evolving disease. Its course and response to treatment are changing more quickly than the literature can describe these changes. The term “HIV positive” refers to a person who has been infected with the virus causing HIV. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) refers to a person who has developed opportunistic diseases as a result of HIV or whose immune system, based on laboratory values, is shown to be significantly suppressed.

The estimated number of persons with AIDS and of persons infected with the HIV virus continues to increase. HIV, once considered a disease that quickly produced complications and death, is now a chronic disease. People with HIV and AIDS are living longer with more productive lives. Therefore, it is impossible for the subspecialist clinician alone to manage the care of this expanding population of patients.

This chapter provides an overview of HIV and AIDS from a primary care perspective. With a thorough knowledge of antiretroviral therapy and chemoprophylaxis, as well as key subspecialty consultation points along the disease process, the primary care provider can continue to provide needed, high-quality HIV care.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

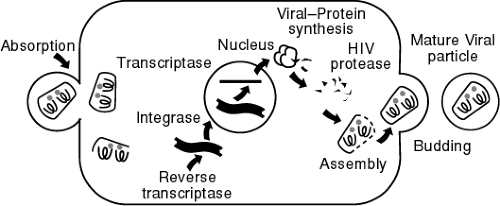

The pathophysiology of HIV disease is quite complex, but an understanding of the basic progression of disease is necessary for optimal clinical management. Multiple sites in the reproductive cycle of the virus must be targeted simultaneously, and the immune system also needs to be bolstered. Understanding these concepts helps in the selection and sequencing of therapies (Fig. 41-1). Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) block the production of viral DNA by inhibiting reverse transcriptase activity, thus preventing infection of new cells. Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) act at the same site as NRTIs, bind directly to reverse transcriptase, and also prevent infection of new cells. Protease inhibitors act at a later point in the HIV life cycle. These compounds inhibit protease from binding with the immature virions after they have budded from an HIV-infected cell, rendering them dysfunctional and noninfectious.

The pathogenesis of HIV-1 depends on the critical balance between viral factors and the host response. With current therapies, the time between primary infection and death can be extended for more than 10 years, depending on the patient’s genetic makeup, the intrinsic health of the immune system, and the timing and choice of antiretroviral therapy. In persons with advanced disease, even after these defense mechanisms have apparently failed, prophylaxis against opportunistic infections alone may still prolong survival.

Course of Infection

After primary exposure to the virus, there is a burst of viral replication during which the virus is disseminated into lymphoid tissue. The immune system responds and in most patients can contain viral replication initially. A prolonged elevation of the amount of virus circulating in the bloodstream (the viral load or viral burden) is highly correlated with the rate of disease progression. This interval before the development of symptoms, termed “disease-free survival time,” is quite variable from one person to the next. It is likely that both viral replication and host defenses are involved in the rate of progression of the disease (Fauci, 1996). With the current use of multidrug therapy, viral replication may remain unmeasurable for more than 10 years. However, what actually triggers the eventual decline of the immune system and resultant increase in viremia is still unclear.

Viral Factors

The virus enters the body as a direct injection (eg, blood transfusion or intravenous drug use) or through sexual contact via a mucosal surface. Concurrent infections, such as a sexually transmitted disease or tuberculosis (TB), increase the rate of transmission. Virus is produced at the rate of 10 billion virions per day, with infected cells having a life span of 2.2 days. The life cycle of the virus is 1.2 days, and it is this rapid growth, resulting in a high level of CD4 cell destruction, that has changed the way the disease is managed clinically (Perelson et al, 1996).

Immune System Response

Lymphoid tissue is the general reservoir for the virus. All immune cell types are affected, although the CD4 cells and monocytes are the main targets. Although the use of protease inhibitors usually decreases the amount of circulating virus, a simultaneous increase in CD4 cells does not always result. This may be because HIV not only causes direct cell destruction but also may have a role in producing programmed cell death (apoptosis).

The immune system is regulated by cytokines, soluble proteins that make up a complex messenger network to control gene activation and the expression of cell surface receptors. There are cytokines that stimulate the production of HIV and

those that suppress replication. The same cytokine may produce opposite results at different times in the life cycle of cells. The complexity of the immune system and of HIV itself makes the development of useful clinical therapies a very difficult task.

those that suppress replication. The same cytokine may produce opposite results at different times in the life cycle of cells. The complexity of the immune system and of HIV itself makes the development of useful clinical therapies a very difficult task.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

If current trends continue, 60 to 70 million adults will have been infected by the year 2000 (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [CDC], 1997b). Sub-Saharan Africa has the most HIV-infected persons (18.5 million); Asia has the second highest number (4.7 million). The Americas have represented the third largest number of HIV infections (2 million in Latin America and the Caribbean and 1 million in North America). The United States has the highest number of reported AIDS cases in the world: 581,429 cases and 362,004 fatalities (CDC, 1996).

The pattern of HIV epidemiology in the United States is evolving. There has been a shift in the epidemic to minority populations, women, heterosexuals, and adolescents (CDC, 1997b). HIV infection is the second leading cause of death in persons ages 25 to 44. Approximately 1 in 300 persons in the United States is infected with HIV.

Some positive trends have also emerged. AIDS incidence among children has declined by 30%, probably the result of the use of zidovudine to prevent perinatal transmission (Quinn, 1996). For the first time, there has been a decline in the AIDS death rate (by 13% in 1996). However, the death rate declined by 15% for men while increasing by 3% for women. Death rates declined by 6% for injection drug users and by 18% for homosexual men while increasing 3% for persons infected through heterosexual contact (CDC, 1997b).

Cultural Factors

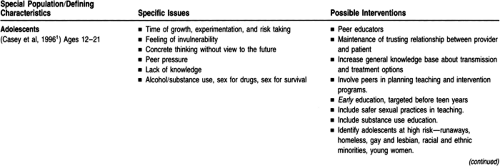

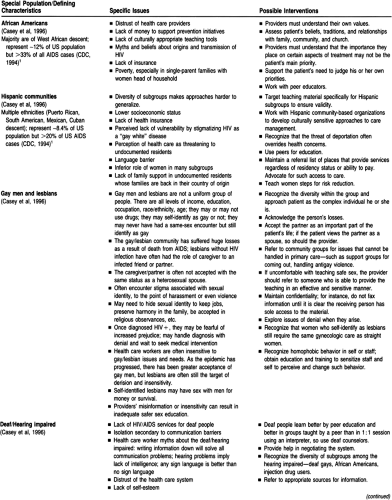

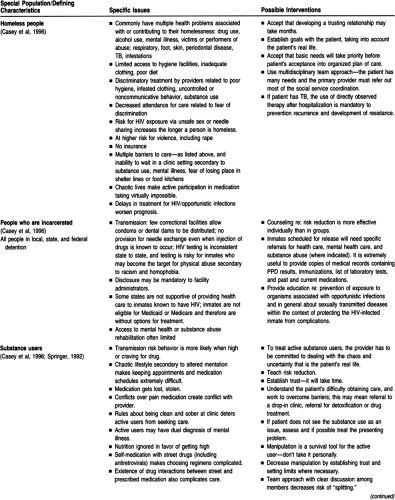

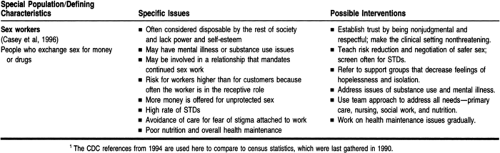

Within the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic is the provider’s obligation to understand how culture and subsequent belief systems affect health promotion. Often referred to as “special populations” issues, HIV has invaded every population and culture. Understanding diversity has a critical impact on a provider’s ability to function effectively and treat appropriately. The effective outcome may be to prevent transmission, provide treatment or access to clinical trials, or to identify sources of support in special population communities. Table 41-1 is a brief summary of special populations, listing definitions, issues, and options for intervention. Specific referral sources may be found in the resources list toward the end of this chapter.

Socioeconomic Factors

HIV infection has crossed socioeconomic lines in ways that are uncharacteristic of other infectious diseases. Initially considered a disease of gay white males, HIV has infected and affected the wealthy and famous, the middle class, and the extremely disadvantaged. Epidemiologically in the United States, financial and social issues have had an impact on disease transmission, treatment, and survival.

HIV infection is now found along all racial, ethnic, gender, age, and economic lines. Particularly in urban areas, HIV infection is concentrated in people of minority groups in inverse proportion to their numbers in the population (CDC, 1994a; Byerly & Deardorff, 1994). Within racial and ethnic groups, women and adolescents are becoming infected at a faster rate than ever before.

Although injection drug use is practiced across socioeconomic lines, it is concentrated in areas where racial and ethnic minorities and economic disadvantage exist. These are the same neighborhoods where a lack of money and infrastructure makes it extremely difficult to increase HIV awareness and prevent transmission. Prevention strategies such as free needle exchanges or distribution of condoms have been opposed in some communities.

Women and HIV

From 1990 to 1996, the incidence of AIDS rose three times faster in women than in men. Women now account for more than 92,200 (15%) of the cumulative AIDS cases in the United States (CDC, 1997b). For the first time, heterosexual sex rather than injection drug use is the leading cause of HIV transmission in women. African American and Hispanic women have consistently accounted for nearly 75% of AIDS cases, and in 1996 African American women represented more than half the new cases of AIDS (CDC, 1997b). As is the case for men, AIDS is the second leading cause of death for women ages 25 to 44. The prevalence of HIV infection among childbearing women nationwide is 1.6 per 1000, accounting for approximately 6500 births (Gwinn et al, 1991; Gwinn & Wortley, 1996).

Because the rate of HIV infection is disproportionately high among impoverished minority women, the social context of their lives is central to their experience and concerns about HIV. The primary care provider cannot separate the issues of poverty, minority status, substance use, gender, domestic violence, and isolation from medical care. Health care use is often sporadic and crisis-oriented as the competing concerns of housing, food, and health care for family members mesh (Anastasio et al, 1995; Hellinger, 1993; Casey et al, 1996; Ragsdale et al, 1995; Fox, 1995).

Although the natural history of HIV disease appears to be the same for both women and men, there tend to be some differences in clinical manifestations. Women appear to have a greater incidence of candidal esophagitis, a greater incidence of mucocutaneous herpes simplex ulcerations, and a low incidence of Kaposi sarcoma.

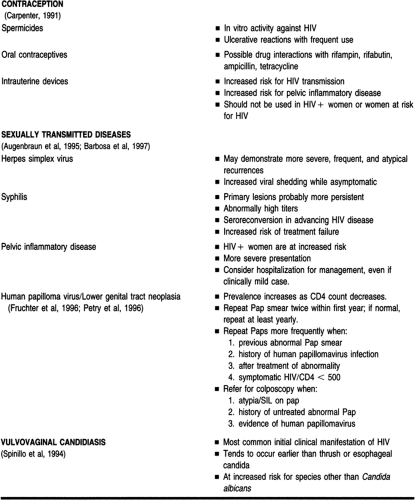

HIV may affect contraception as well as gynecologic problems (their frequency, presentation, natural history, and response to treatment). The primary care provider must be aware of the impact of HIV on these issues, for it can enable the identification of women at risk for HIV and can improve care to HIV-positive women (Table 41-2).

Studies in the United States show that HIV has not been demonstrated to affect the course or outcome of pregnancy; likewise, pregnancy does not affect HIV progression in woman (U.S. Public Health Service, 1997). Infection from the mother during pregnancy accounts for approximately 90% of cases of pediatric AIDS in the United States (CDC, 1994b). The use of zidovudine during pregnancy and labor and at delivery reduces the risk of HIV transmission by two thirds (CDC, 1994b). Before discussing a chemoprophylaxis regimen with the patient, the primary care provider should contact the CDC for the most current recommendation, as well as an obstetrician who specializes in HIV or an HIV subspecialist. Then the provider should discuss with and offer the patient the most current antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum regimen (Casey et al., 1996; Landers, 1997).

In 1995, the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) issued recommendations for HIV counseling and voluntary testing of all pregnant women (CDC, 1995b). In addition, some states require testing of all newborns.

Occupational Hazards

As the AIDS epidemic expands, an increasing number of health care workers will encounter patients infected with HIV. The threat of occupational exposure to HIV is real but small. The average risk for HIV infection from all types of percutaneous exposures to HIV-infected blood is 0.3%, although it may be greater when the exposure involves a larger blood volume or a higher HIV titer in blood (MMWR, 1996).

Currently, there are 52 documented cases of HIV infection in health care workers as a result of occupational exposure (CDC, 1996). The Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), in an effort to minimize such exposures, developed the Bloodborne Pathogen Standard (Rules and Regulations, 1991). These government regulations require employers to protect employees by using universal precautions, having written exposure control plans, and adhering to the postexposure prophylaxis recommendations of the USPHS.

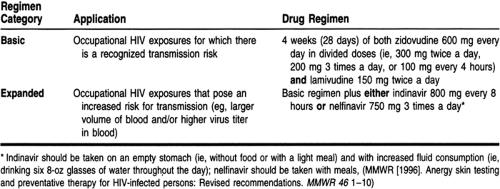

Postexposure prophylaxis with zidovudine (AZT) has been associated with a decrease of approximately 79% in the risk for HIV seroconversion after percutaneous exposure to HIV-infected blood (MMWR, 1996). Subsequently, the USPHS revised its recommendations to include lamivudine (3TC) and protease inhibitors, indinavir and/or nelfinavir (Table 41-3). In addition to chemoprophylaxis, the recommendations include the following:

Postexposure prophylaxis should be implemented in consultation with persons having expertise in antiretroviral therapy and HIV transmission.

Postexposure prophylaxis should be recommended in cases with the highest risk of HIV transmission and offered to those with lower-risk exposures.

Postexposure prophylaxis should be administered within 1 to 2 hours after exposure for 4 weeks.

If the patient’s HIV status is unknown, postexposure prophylaxis should be administered on a case-by-case basis.

Health care workers should receive counseling and medical evaluation at baseline and periodically for 6 months.

If postexposure prophylaxis is used, drug toxicity monitoring (complete blood count, renal and hepatic function tests) should be done at baseline and at 2 weeks.

Health care workers who receive postexposure prophylaxis should be enrolled in an anonymous registry developed by the CDC.

Prevention of exposure remains the key. Adherence to universal precautions and the use of needleless and protected needle intravenous systems can reduce the number of exposures in the workplace (Kelen et al, 1991; Ippolito et al, 1997).

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

The finding of opportunistic infections makes it easier to diagnose HIV infection and AIDS. Patients, especially if asymptomatic, often do not know they are infected and may not even know they are at risk. A sexual history and a drug history should be part of every patient’s evaluation. In addition, a history of blood transfusions before 1986 should be noted.

Screening for HIV

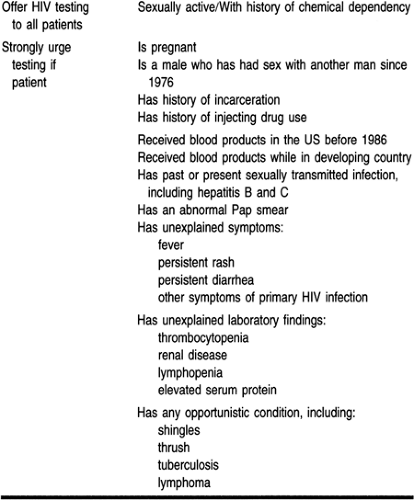

Early diagnosis of HIV with appropriate treatment can offer a patient many years of productive life. Making the diagnosis requires primary care providers to consider HIV screening for most patients and to suspect HIV infection in many situations (Table 41-4). With the spread of the epidemic into lower-risk populations, it is prudent to offer HIV screening to all sexually active patients. In addition, it is good practice to offer testing to any patient with a history of chemical dependency because of the possibility of unprotected sex while intoxicated. The offer of testing provides an excellent opportunity to raise awareness of HIV among patients and to discuss the need for protection.

Risky behaviors can also be assessed during the history. Ownby, Ferri, and Vlahov (in Casey et al, 1996) stratified risky behavior as follows:

The rate of HIV transmission is higher in injection drug use than in unsafe sex.

The more sexual partners, the greater the risk for HIV exposure.

Sexual activity has a high, medium, and circumstance-dependent HIV risk.

The most appropriate teaching strategy is one chosen by a provider who is aware of the patient’s life, including cultural and socioeconomic factors. In addition, providers need to explore their own comfort with teaching risk-reduction behaviors. This is achieved by confronting their fears and prejudices as well as practicing such teaching.

Physical Exam

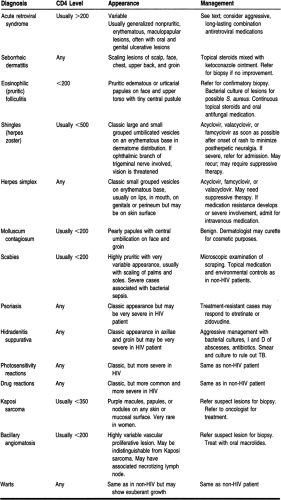

The standard physical exam includes serial assessments of weight and nutrition. A meticulous exam of the scalp and skin is essential (Table 41-5). The provider may first suspect HIV infection on finding specific conditions in the mouth. Oral hairy leukoplakia is a benign thickening of the mucosa in a corrugated pattern, often on the lateral surfaces of the tongue. Thrush (candidiasis) may present as erythema or more commonly as white, nonadherent plaques on the tongue, palate, buccal surfaces, or pharynx. The infection responds well to local or mild systemic antifungals. With more advanced immunosuppression, the infection involves the esophagus and may cause difficulty in swallowing solids. Severe, recurrent, or persistent herpes labialis is also common and responds to acyclovir and related drugs. Advanced gingivitis and periodontitis are also common and may interfere greatly with nutrition. Extensive treatment by a dentist is usually necessary. Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis can also present as oral lesions.

A funduscopic exam, a survey of lymph nodes, a neurologic exam (focusing on possible cognitive deficits and peripheral neuropathies), a routine cardiopulmonary exam, and a careful genital/rectal examination for coexisting diseases must also be done during the initial assessment, and any time there is a suspicion that one of these organ systems may have become involved.

Disease Course

ACUTE HIV INFECTION

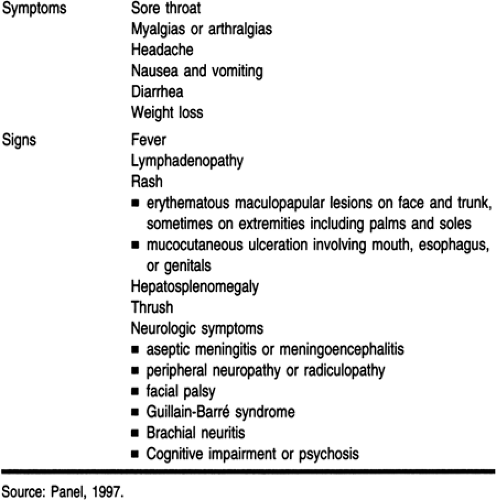

Although a patient may present at any point during the disease, the first exposure to HIV infection typically manifests as a flulike syndrome. From 50% to 90% of patients acutely infected will have some or all of the typical symptoms and signs, such as headache, fever, rash, and myalgias (Table 41-6). Symptomatic patients will have a marked transient drop in the CD4 count, and a few may even develop frank AIDS-defining conditions

that resolve with a rebound in the CD4 count and a drop in viral load. Patients with severe acute retroviral syndromes are more likely to have a rapidly progressive downhill course. This viral syndrome lasts several days and then resolves spontaneously.

that resolve with a rebound in the CD4 count and a drop in viral load. Patients with severe acute retroviral syndromes are more likely to have a rapidly progressive downhill course. This viral syndrome lasts several days and then resolves spontaneously.

EARLY DISEASE: ASYMPTOMATIC STAGE

With the resolution of any acute retroviral syndrome, the patient enters a phase of asymptomatic disease that usually lasts 5 or more years. Some patients, so-called nonprogressors, remain asymptomatic for 20 or more years, probably because a nonlethal, defective strain of virus has infected them. Other patients have a rapid downhill course and die within 2 or 3 years (the “crash and burn” syndrome), usually because mutations in the virus have produced a highly lethal strain.

HIV infection begins with acute transmission and primary infection, followed by seroconversion about 6 to 12 weeks later. Although there appears to be a period of clinical latency, we now know that viral replication is constant (see the section on pathophysiology below). The current staging of HIV disease is not clinically distinct. Although the CDC revised the AIDS-defining criteria in 1993 (CDC, 1993), this system does not take into account the amount of HIV present (the viral load or viral burden). As measures of circulating HIV RNA become more accessible, this staging system will need significant revision.

A prospective evaluation of gay men called the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study has shown that persons with persistently high levels of viremia more rapidly progress to AIDS and death (Mellors et al, 1996). The advent of combination antiretroviral therapy has significantly affected the course of disease; thus, prediction of survival is not as clear as it may have seemed before 1995. Even when the disease has failed to respond to these therapies, life can be prolonged simply by using recommended prophylaxis for known opportunistic infections.

MONITORING THE RATE OF PROGRESSION

The progression of HIV disease is quite variable. Newer therapies change the prognosis, and as providers become more adept at managing intercurrent illness, the course is prolonged (Kitahata et al, 1996). Both the durability and the magnitude of the virologic response affect progression to AIDS. Recent studies have shown that the viral load at baseline is a strong predictor of the rapidity of progression to AIDS, regardless of the CD4 count (Mellors et al, 1997; DHHS, 1997).

Persons infected with HIV-1 represent a normal distribution of response to the virus. A few are rapid progressors who develop full-blown AIDS in 2 to 3 years. Five percent to 12% are long-term nonprogressors who have lived for 10 or more years without symptoms or therapy (Cao et al, 1995; Pantaleo, 1995). The majority fall somewhere in between and need to be characterized by their immune response and their burden of viral activity.

STAGING THE DISEASE

Laboratory evaluation of the blood is especially important in staging the disease. Baseline screening for HIV-associated diseases such as syphilis, cervical cancer, and hepatitis B help stage HIV disease, as well as identifying anemia and neutropenia (see the section on diagnostic studies below). However, the most important blood tests for determining the patient’s stage of HIV disease are the CD4 T-cell count and quantitative HIV RNA (viral loads). The CD4 count is known to be influenced by many factors such as diurnal variation, intercurrent infection, and substance use. Since the viral load has come into use, most surrogate markers are no longer as useful as they once were for staging. Viral quantitation should not be obtained when the person is ill or within 4 weeks of an immunization, because the viral burden is increased in those situations.

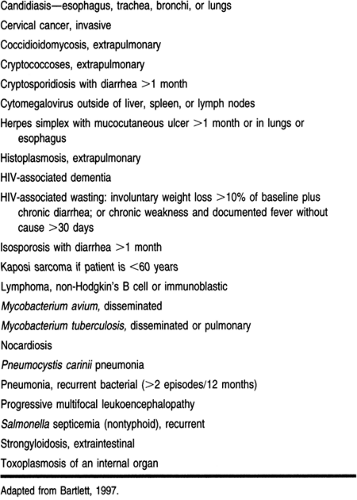

Originally, the definition of AIDS was made clinically, including multiple conditions of immunosuppression. In 1993, the definition was expanded to include invasive cervical carcinoma, recurrent bacterial infections, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Table 41-7). Persons with a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mm3 were also classified as having AIDS, regardless of their clinical picture.

The current staging system for HIV disease uses the absence or presence of symptoms and is related to the CD4 count. However, staging and consequently management are more appropriately based on viral load. Exact correlations of these two measures have not been clearly established, but a change in the plasma viral load of 2.5-fold or more probably indicates a true biologic change (Casey et al, 1996).

LATE DISEASE

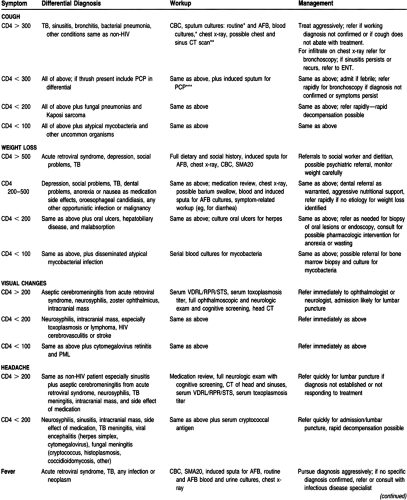

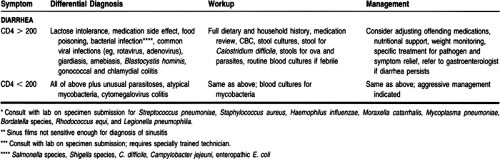

Later during the disease course, the patient may develop opportunistic infection, wasting syndrome, chronic diarrhea, or any of the other AIDS indicator diseases listed in Table 41-7. The primary care provider must be able to assess HIV-positive patients in a rapid and systematic manner, regardless of their CD4 count, and identify serious opportunistic complications. Table 41-8

presents one such approach. The primary care provider should be familiar with the manifestations of these diseases.

presents one such approach. The primary care provider should be familiar with the manifestations of these diseases.

Opportunistic Infections

Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss all opportunistic infections in detail, the primary care provider should be familiar with the identification and significance of certain infections. The prevention of opportunistic infections is well defined. The guiding principle is simple: primary prophylaxis, when possible, is best (See Table 41-9). Currently, the USPHS and the Infectious Disease Society of America (CDC, 1997c) strongly recommend primary prophylaxis as a standard of care for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), Mycobacterium avium complex, Toxoplasma gondii infection, and TB. In addition, prophylaxis for Streptococcus pneumoniae and varicella is warranted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree