Headache

Virginia E. Robertson MD

Mary E. McCormack RNCS, FNP-C, MPH

Headache is a challenging symptom for both patient and provider. Etiologies are varied and include idiopathic and specific conditions, with prognoses ranging from benign to life-threatening. Further, depending on the nature of the headache syndrome, the impact on the patient and on society may be minimal or major. Nearly 15 million people in the United States in 1994 had headaches (National Center for Health Statistics, 1995), and headache is among the top 10 causes for primary care visits (Kumar & Cooney, 1995). Thus, it is important to recognize serious secondary causes of headache and manage the benign yet potentially disabling primary headaches.

The primary headache syndromes are those headaches that are considered idiopathic, including migraine, tension-type headache, and cluster headache. Secondary headache syndromes usually can be found to have a treatable cause, which will result in “cure” of the headache. These headaches may be caused by a wide variety of conditions, from the relatively rare brain tumor and subarachnoid hemorrhage to the more common and benign systemic viral syndromes. Diagnostic classifications of headaches are discussed below, using the International Headache Society (IHS) criteria (International Headache Society, 1988).

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

The symptom of headache arises when pain is referred to the surface of the head from either intra- or extracranial sources. Although the anatomy and pathophysiology of all headache syndromes have not been fully elucidated, certain structures and contributing physiology are understood and aid the provider in both diagnosis and treatment.

Anatomic Sources for Headache

Intracranial structures that are implicated in some headaches include the periosteum, the dura at the base of the skull, the venous sinuses, the anterior and middle meningeal arteries, and the upper cervical nerves and cranial nerves V, VII, IX, and X. Pain from intracranial sources above the tentorium is usually referred via cranial nerve V to the frontal, orbital, and temporal regions. Pain originating below the tentorium and in the posterior fossa is typically transmitted via the facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves and the upper cervical nerves to the ear, nose, throat, and occiput. The brain parenchyma and bony skull themselves are almost completely insensitive to pain, as are certain cranial nerves (I, II, and VIII).

Extracranial structures that can give rise to headache include the skin, fascia, muscles, extracranial vasculature, ears, nasal mucosa, eyes, teeth, and cervical spine (Goroll et al, 1995; Stevens, 1993). Pain referred from these structures usually directly overlies the structure.

Pathophysiologic Mechanisms for Headache

Several types of stimuli affect these structures and become detected as pain. Dilatation of intra- and extracranial vasculature occurs in migraine, giant cell arteritis, malignant hypertension, eclampsia, transient ischemic attacks, arteriovenous malformation, and alcohol or drug withdrawal. Contraction or tension of cranial and cervical muscles is implicated in tension-type headache, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and head or neck trauma.

Distention, stretching, or displacement of the dura or cranial nerves may be associated with an increase or decrease in intracranial pressure, mass lesions, or mass effect from bleeding. Inflammation of the meninges, as in meningitis or meningoencephalitis, or of cranial or spinal nerves, as in trigeminal neuralgia, mass lesions, and cervical radiculopathy, also can cause headache. Iritis and angle-closure glaucoma may yield headache along the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V, first division), in addition to eye pain (Wyngaarden, 1992).

The known pathophysiology of the primary headache syndromes reveals complex neurohormonal and neurochemical contributors. Migraine, for example, involves both vascular and neurologic factors. Vascular changes include constriction of branches of the carotid artery, causing the prodromal symptoms, followed by arterial dilation, causing the pain, and ending with arterial wall edema, which accounts for the sometimes protracted pain. However, regional blood flow does not explain all aspects of migraine. A neurologic component may be mediated by a phenomenon called cortical spreading depression, which decreases the excitability of central neurons to neurochemical transmitters.

One transmitter currently under focus is serotonin, which has been found to be released abnormally from platelets during migraine. A rich supply of serotonergic nerve endings are found in the meningeal vasculature, as well as in the peripheral trigeminal nerve (Zagami, 1994). Such findings have helped to create new treatments, including sumatriptan, a serotonin-1d receptor agonist.

Hormonal and neurohormonal changes are also thought to be involved in some headaches. For example, hypothalamic and neurohormonal alterations, as well as vasomotor disturbances, have been implicated in the pathophysiology of cluster headaches (Kudrow, 1994). Also, the preponderance of women migraine sufferers after menarche, as well as the variation in migraine occurrence for some women taking birth-control pills, have long implicated estrogens as contributory to migraine.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Epidemiologic surveillance of headache has improved since the advent of the IHS classification system because it provides specific diagnostic criteria for different headache syndromes. However, other methodologic differences between studies remain problematic. Studies using general versus referral populations, differing age ranges, self-administered headache questionnaires versus structured interviews, and self-reported versus provider-reported diagnoses have yielded varying interpretations of prevalence and sociodemographic data. The use of IHS diagnostic criteria to study general populations, however, has shown some consistent headache patterns between studies and has challenged certain prior concepts.

Prevalence

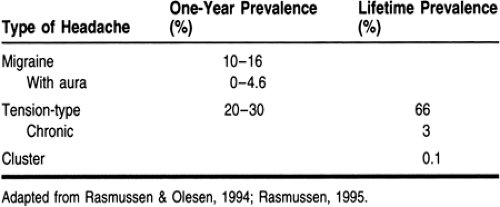

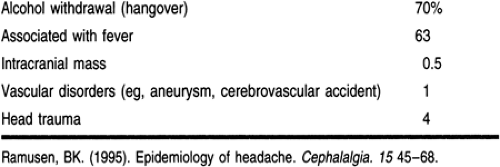

Estimates of headache prevalence for the U.S. population have been derived by the National Health Interview Survey, most recently conducted in 1994 (National Center for Health Statistics, 1995). In household interviews, nearly 4 million people reported that they experienced acute nonmigraine headaches in the prior 3 months that were severe enough to limit their activities or prompt medical attention. Of these, 30% were among people ages 5 to 17 and 34% were between ages 25 and 44. For migraine, 11 million people reported that they have migraine as a chronic condition. Of these migraine sufferers (“migraineurs”), 10% were younger than 18 years old, and 60.5% were 17 to 44 years old. The predominance of headache among working-age adults creates great financial impact in the United States as a result of work lost from absences and disability (Stang & Osterhaus, 1993). Table 54-1 shows typical prevalences for the primary headache syndromes.

Among secondary headache syndromes, many of the relatively benign types are highly prevalent. The more serious secondary headache syndromes are, fortunately, relatively rare. Table 54-2 provides prevalence rates of some secondary headaches.

Age

Primary headache syndromes can have their onset at any age, but typical patterns are seen. Migraines tend to present in the second and third decades, whereas tension-type headaches usually have an onset in the second decade. The peak prevalence of migraines tends to be around age 40 years in women and 35 in men (Stewart et al, 1992), whereas tension-type headaches peak in the middle to late 40s for both men and women. Peak age of presentation for episodic tension headaches occurs a few years before the peak for chronic tension headache (Rasmussen, 1995). This trend has contributed to the controversial idea that episodic headaches may transform into chronic headaches (Ziegler, 1995).

Both types of headache show decreasing prevalence with aging, especially after the 50s, although it is unclear whether this trend is related to the natural history of these headaches, to increased treatment, or to other factors (Rasmussen & Olesen, 1994). The proportion of migraineurs reporting disability with headaches appears to remain constant regardless of age (Stewart et al, 1992).

In contrast, vascular and other secondary headaches are more prevalent in the elderly, necessitating close attention to the presentation, or change in pattern, of headache in the elderly.

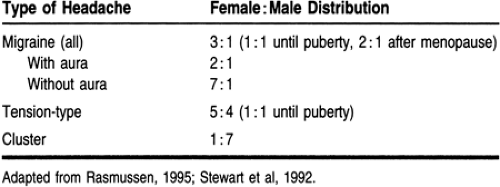

Gender

Among the primary headache syndromes, migraines and tension-type headaches disproportionately affect women. The 1-year prevalence for migraines is 3% to 9% in men and 13% to 20% in women. The gender differences are further accentuated by age and subtype of headache, as shown in Table 54-3.

Cultural Factors

Headache, with its major symptom being pain, is subject to cultural differences in patient experience, meaning, and outcomes. Until recently, migraines and tension-type headaches were thought to be more common in industrialized countries or in certain ethnic groups, but this conclusion has not, in fact, been supported in population-based studies (Rasmussen, 1995). In contrast, for migraine, the similarity of prevalence between different populations has been cited as partial evidence for the underlying biologic, rather than cultural, basis of migraine (Goadsby, 1994).

Socioeconomic Factors

Early studies on headache prevalence concluded that migraines were more common in higher socioeconomic classes, but more recent studies have challenged this finding (Rasmussen, 1995; Stang & Osterhaus, 1993; Stewart et al, 1992). However, several studies have shown that migraine patients with higher income do have more physician visits (Lipton et al, 1992; Rasmussen & Olesen, 1994) and have been given an IHS-consistent diagnosis from a physician (Lipton et al, 1992).

In terms of socioeconomic impact, migraine headaches contributed to 1.5 million person-days of work lost as a result of patients being bedridden and 2.8 million person-days of restricted activity in 1989 (Stang & Osterhaus, 1993). For nonmigraine headaches, the 1994 National Health Interview Survey data attributed 3.5 million bed-days and more than 8 million restricted activity days (similar data were not cited for migraines).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

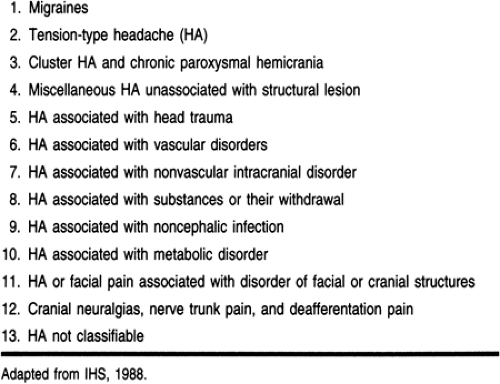

In 1988, the IHS published “Classification and Diagnostic Criteria for Headache Disorders, Cranial Neuralgias, and Facial Pain” in an effort to facilitate headache research and to improve clinical care. Although diagnostic criteria for headache had been established before, the IHS classifications and criteria are the current standards because of their comprehensive and organized approach, permitting more precise diagnoses of the symptom of headache.

The IHS classifies headaches according to their unique definition or pathologic basis (Table 54-4). The IHS system then provides a list of diagnostic criteria that characterize each headache syndrome by its specific features—its history, pattern of recurrence, and known contributing factors.

Clinical use of the IHS system, therefore, relies on the ability of the provider to elicit a sound and complete history. Indeed, because primary headaches have no physical markers, the history is the provider’s prime tool for diagnosis. The physical exam and laboratory workup are used selectively to detect other illnesses or specific treatable entities when indicated.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

As many as 50% to 85% of headache sufferers, depending on the type of headache, do not seek care or obtain a formal diagnosis (Lipton et al, 1992; Rasmussen & Olesen, 1994). Those who do seek care may have already had headaches for some time; others come in very early, at the first sign of headache. In general, the secondary headache syndromes present more acutely or can have more serious consequences, whereas the primary headache syndromes often have a benign prognosis but can be quite limiting if not well diagnosed or treated.

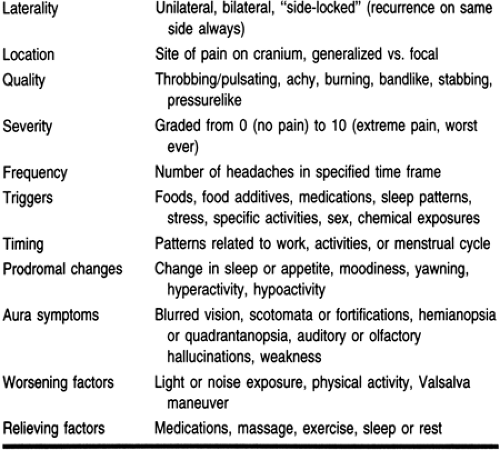

The headache history (Table 54-5) should be used to characterize the headache and discern any acute or serious features. Unusual symptoms should be assessed: headache that flares during coughing, sneezing, or physical exertion (including sex); headache described as the “worst ever”; ongoing neurologic symptoms and signs during or after the headache; seizures or syncope; red eye; and others (see “Referral Points and Clinical Warnings” below). Headache that awakens the patient from sleep is a another feature that should alert the provider to possible intracranial mass.

Additional essential elements of the history include:

Medications, including all prescribed medications and over-the-counter drugs. Some cause headache as a direct side effect, such as nitrates and calcium channel blockers; others contribute to rebound headache, such as analgesics containing caffeine or ergotamine.

Substance use, including any recent use of alcohol or other substances that cause acute or withdrawal headache

Trauma, acute or distant

Concurrent fever and change in mental status

Family history, especially of migraines

Nutritional and occupational histories

Recent stressors or symptoms of anxiety and depression

Personal medical history of hypertension, chronic lung diseases, diabetes, and other chronic diseases that put the patient at risk for metabolic or medication-induced headaches.

The physical exam is used to find any secondary causes of headache and to screen for warning signs of serious etiologies. A general exam including a complete neurologic exam is essential. Fever, abnormal mental status, restricted range of motion on neck exam, hypoxia, purulent nasal discharge, and clicks on jaw movements may all point to secondary causes of headache. Warning signs of neurologic compromise include persistent visual field defects, focal weakness or sensory loss, seizures, orbital bruits, change in mental status (confusion, drowsiness), asymmetrical pupillary response, and papilledema. Any unusual finding on the history or physical exam should prompt the provider to consider a more sophisticated workup, which may include immediate consultation with a neurologist or infectious disease specialist or referral to the emergency department.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree