CHAPTER 4 General indications and contraindications

Peripheral nerve block: indications

Surgery

A thorough knowledge of descriptive and topographic anatomy, especially with regard to nerve distribution, is beyond discussion. It is a condition which anyone desirous of attempting the study of regional anesthesia should fulfil. The anatomy of the human body must, besides, be approached from an angle hitherto unknown to the medical student and with which the average surgeon is not at all familiar.1

Gaston Labat wrote these words at a time when deep ether anesthesia was required to provide adequate muscle relaxation, especially for abdominal surgery. The problems associated with deep ether anesthesia included nausea, vomiting, and atelectasis and subsequent pneumonia. Therefore, the benefits of regional anesthesia were readily apparent. The practice of regional anesthesia still holds attraction, possibly because of its positive effects on secondary outcomes such as postoperative nausea and vomiting, postoperative confusion, and rapid return to ‘street fitness’. Evidence of a positive influence on the ‘hard’ postoperative outcomes of morbidity and mortality is more difficult to come by, although a number of studies have shown benefit in specific circumstances.2–4 Practicing regional anesthesia is also an opportunity for anesthesiologists to employ their individual skills, and so can be an important source of professional satisfaction. Practitioners are responsible for acquainting themselves with the anatomy to which Labat refers and to which a large part of this textbook and DVD-ROM is directed. This knowledge lies at the core of successful regional anesthetic practice and the avoidance of many of its complications.

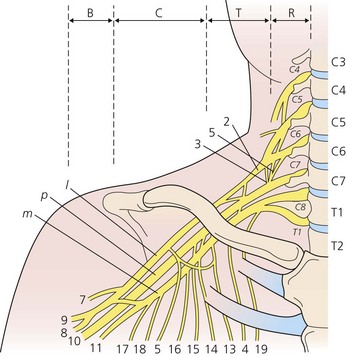

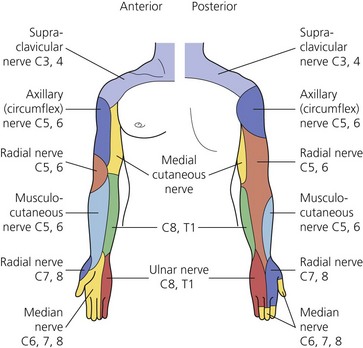

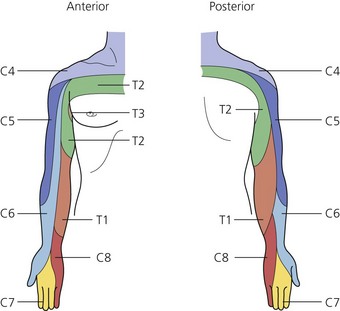

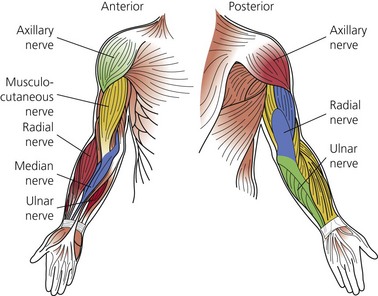

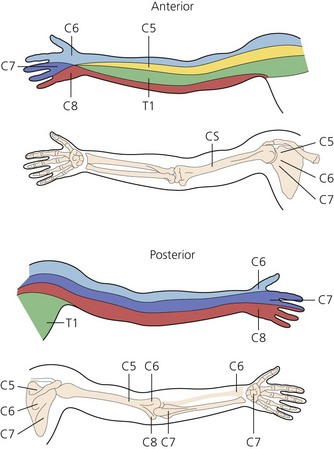

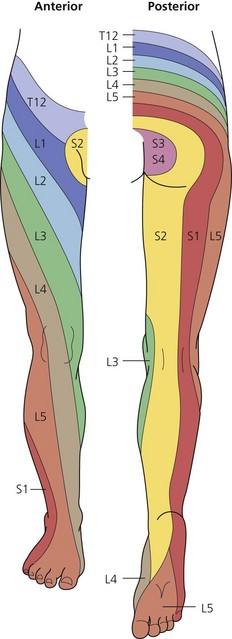

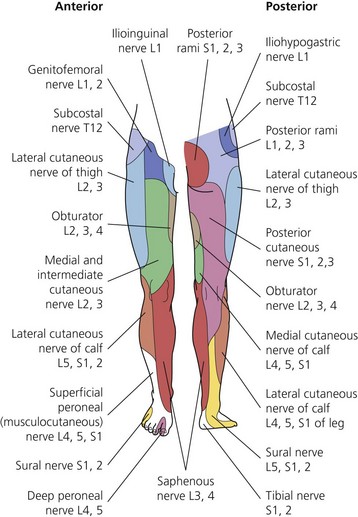

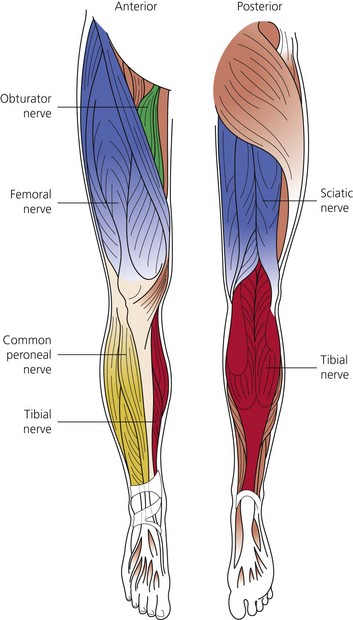

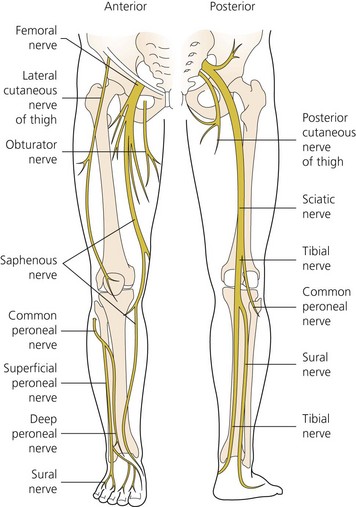

The dermatomes and myotomes of the body and limbs are shown in Figures 4.1–4.9.5 The selection of a regional anesthetic technique appropriate to a particular surgical intervention becomes more straightforward when one can answer the following questions:

Management of acute pain

Pain arises from the direct activation of primary afferent neurons. It is often associated with tissue damage and an inflammatory response, especially in the clinical setting. The inflammatory response has both cellular and neurogenic components. Activation of lymphocytes, macrophages, and mast cells, and the release of neuropeptides such as substance P and neurokinin A result in the further release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine, bradykinin, and the products of arachidonic acid metabolism.6–9 These chemicals can sensitize high-threshold nociceptors to produce the phenomenon of peripheral sensitization. The resultant area of primary hyperalgesia is characterized by an increased responsiveness to thermal and low-threshold mechanical stimuli at the site of injury.

In addition to the area of primary hyperalgesia, a zone of secondary hyperalgesia develops in the uninjured tissues surrounding the site of injury. No changes occur in the threshold to stimuli of the nerves in this area. Changes in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and elsewhere account for this central sensitization.10 Changes that occur in the dorsal horn in association with central sensitization include an expansion in receptive field size, increased response to stimuli, and a reduction in threshold. These changes are important in the development of both acute and chronic pain.11,12

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) exert their action by blocking the cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzyme pathway. With traditional agents, this has involved the inhibition of both the COX1 and COX2 isoforms. Reductions in pain scores and opioid requirements have been reported with their use. The COX2 isoform is predominantly induced by the inflammatory process, and the recent development and introduction into clinical practice of specific COX2 inhibitors, holds promise for a reduction in side-effects of these drugs.13 Evidence also exists to support a central mechanism of action of NSAIDs in the modification of pain mechanisms.14

The role of opioid drugs in the modification of central pain mechanisms has been long recognized. They act presynaptically to inhibit the release of neurotransmitters from the nociceptive primary afferent neuron. Peripheral nerves are known to manufacture opioid receptors in the cell body and transport them to both the periphery and the dorsal horn. Following tissue injury, the peripheral receptors become active.15,16 Initial interest in exploiting these features has waned somewhat as equivocal results following the intra-articular administration of morphine to treat arthroscopic procedure-related pain have been published.17

Damage to peripheral nerves results in pathophysiologic changes in the nerves themselves.18 Such damage manifests as spontaneous firing, increased sensitivity to non-noxious stimuli, demyelination, and the sprouting of nerve fibers. These changes form the basis for the development of peripheral chronic pain states. Low concentrations of local anesthetic can reduce ectopic activity in damaged nerves, a feature utilized during their systemic administration for the treatment of neuropathic pain.19 Local anesthetic field block combined with wound infiltration has been shown to significantly reduce pain scores and opioid requirements for up to a week following hernia repair.20 Wound infiltration is an integral part of this technique; however, definitive evidence showing prevention in the development of the above changes remains lacking.

The concept and effectiveness of pre-emptive analgesia remain controversial.21 At its heart, however, is the hypothesis that the prevention of noxious inputs occurring during and after surgery will prevent the development of central sensitization. Although it has been demonstrated that early postoperative pain is a predictor of long-term pain, it is not known what degree of noxious input is required, or for how long it must be present to produce long-term changes in the nervous system.22 The logic of combining NSAIDs, opioids, and a regional anesthetic technique (with or without perineural catheter) appears self-evident, yet definitive evidence of benefit in the clinical setting is lacking, and the standardization of study methods is required to allow firm conclusions to be drawn.23–25

Chronic pain

The indications for somatic peripheral nerve block in the management of chronic pain are limited, and the results require careful interpretation. A common indication has been to determine the likelihood of success following surgical decompression or neurolysis of a peripheral nerve. Small volumes of local anesthetic need to be used in this setting to prevent spread to other nerves, and long-acting agents allow one to differentiate the results from the placebo effect, which in itself tends to be short-lived.26

Continuous nerve block

Continuous catheter techniques are gaining widespread use in a number of clinical settings. These include acute pain relief in the inpatient and ambulatory settings, early postoperative rehabilitation, continuous sympathectomy following re-implantation procedures, and the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pain syndromes.27–31 Indeed, there have been published reports of improved surgical outcomes with these techniques, in addition to improved secondary outcomes.32

The concerns regarding continuous techniques have related to infection, catheter migration, high plasma levels of local anesthetic, local myelotoxicity, and neurologic complications. Infection has been reported, yet despite a colonization rate of up to 27%, overt problems appear to be rare.33 Catheter migration can be detected early with regular and routine examination of catheter site and assessment of the nerve block.

Plasma levels of local anesthetic may rise progressively during an infusion. Although the peri-operative rise in α1-acid glycoprotein (GP) has been shown to ameliorate the effect, a seizure rate of 1.2 per 1000 procedures has been reported.34,35 Postoperative protocols, education of carers, and patient cooperation are necessary to detect the early signs of local anesthetic toxicity and ensure the optimal use of this technology.

The incidence of neurologic complications is less than 1% with the use of perineural catheters. This is similar to the rates recorded following multiple single-dose techniques.36 Whether the incidence of complications can be reduced further using ultrasound to guide catheter placement remains to be seen. It should be noted that catheter techniques are often used in major joint surgery such as distraction interposition arthroplasty, which carries an inherent high risk of nerve injury.37