TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

Control of Thermoregulation

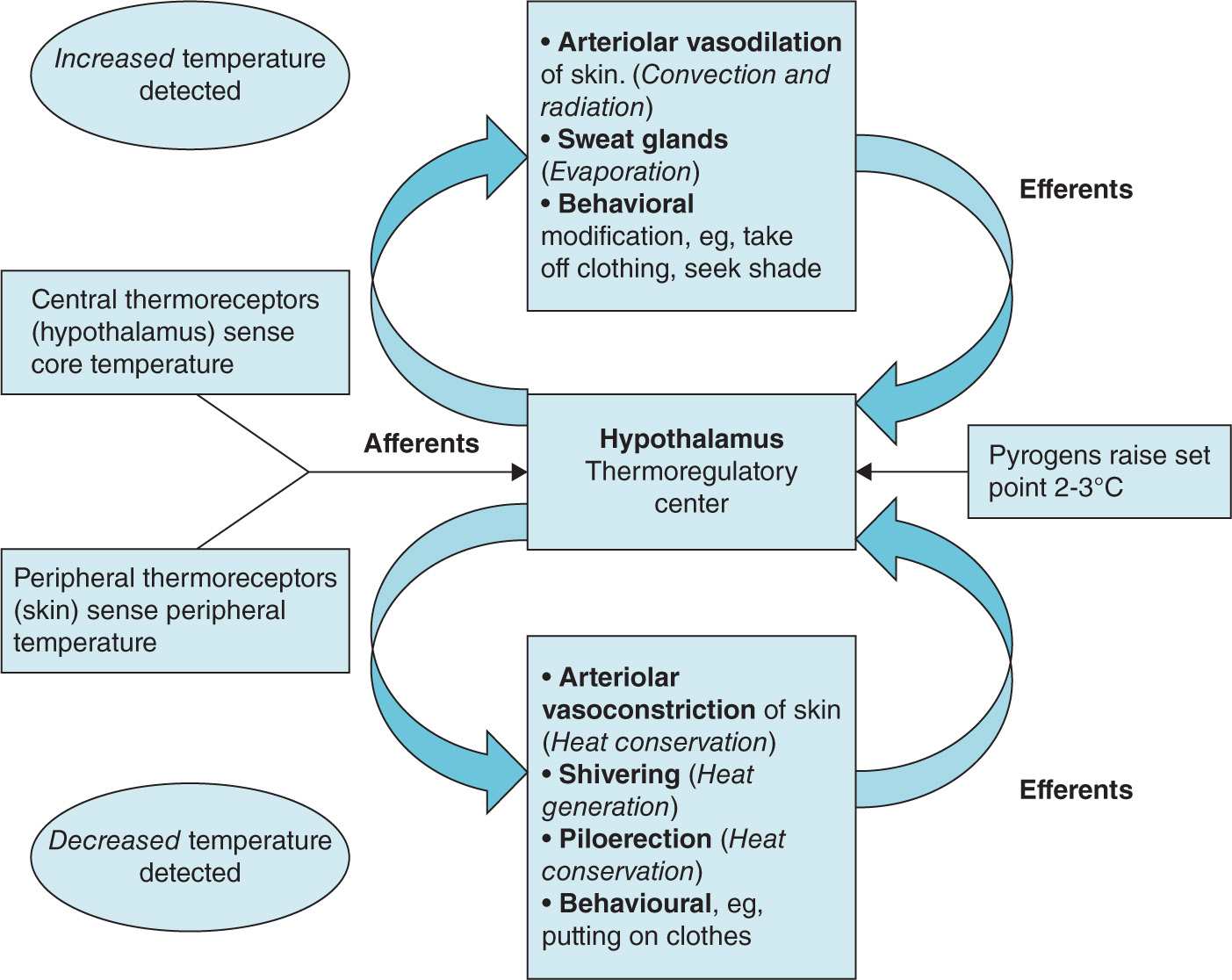

Thermal homeostasis is controlled by the hypothalamus within a range of 36.5°C to 38°C. Fever is defined as a temperature greater than 38°C and is caused by resetting the thermoregulatory threshold of the hypothalamus (eg, by pyrogens released in response to infection), deregulation of heat production (eg, malignant hyperthermia), or dissipation. See Figure 18-1 for a schematic view of thermoregulation.

Figure 18-1. Schematic representation of thermoregulation.

Causes of Fever in Pregnancy

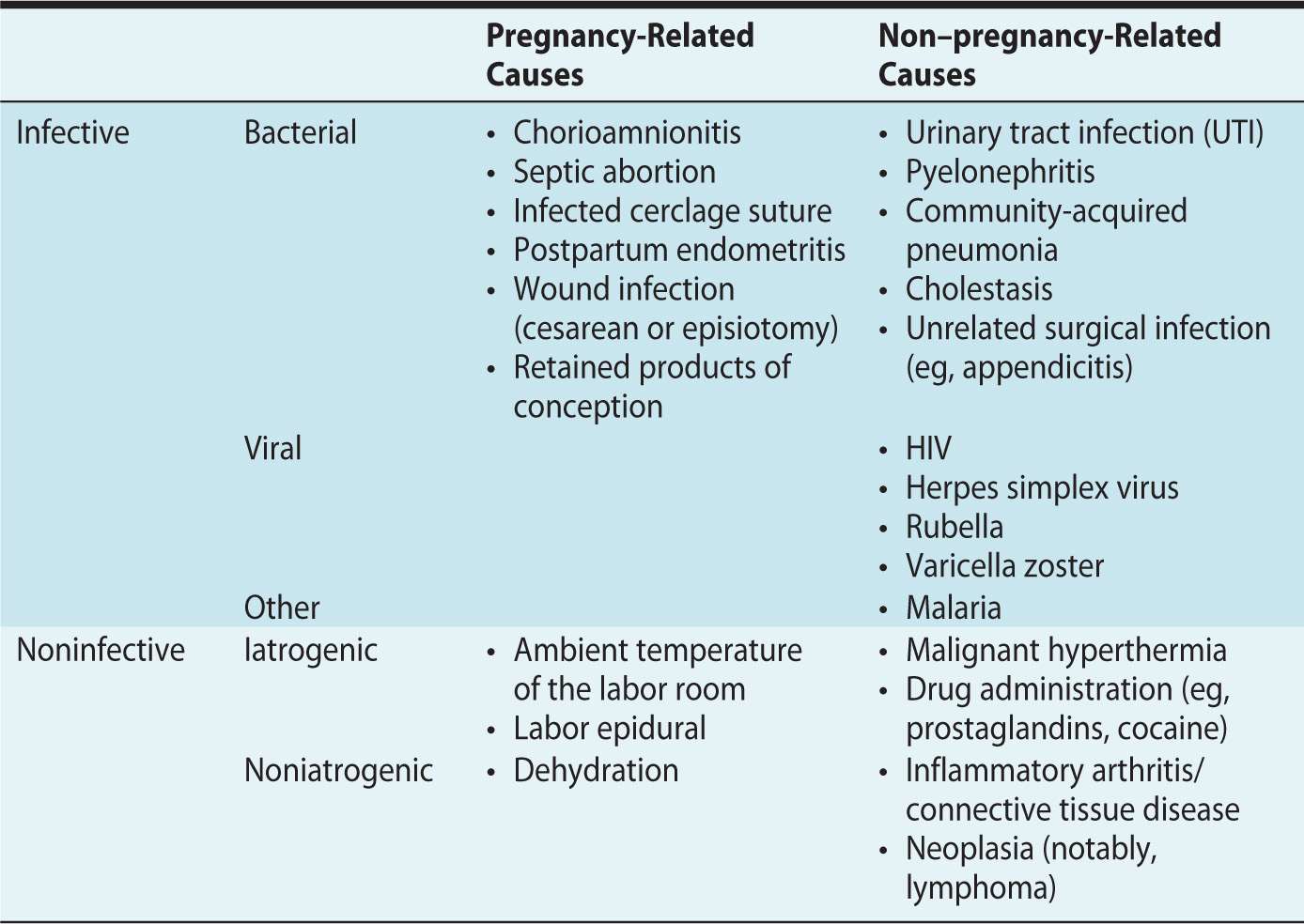

There is a broad differential diagnosis for fever in the parturient, including infective and noninfective causes, which may or may not be directly related to the pregnancy (Table 18-1). Infective disease patterns, incidences, and outcomes vary significantly between more-developed and less-developed regions of the world.

Table 18-1. Causes of Fever in Pregnancy

Predisposition to Infection

Parturients are predisposed to infection for several reasons. These may be physiologic. Parturients may develop relative immunosuppression in order to tolerate fetal alloantigens and prevent fetal compromise and demise.1,2 A pH change in vaginal epithelium may alter the environment for microorganism growth.1 Alternatively, the reasons may be anatomic. Urinary tract dilation and urinary stasis, from a gravid uterus and progesterone, are risk factors for urinary tract infection (UTI).1,2 Increased intra-abdominal pressure and upward diaphragm displacement by a gravid uterus increases basal atelectasis, potentially predisposing to pneumonia.1

Peripartum, there are additional risk factors:

• Premature rupture of membranes (PROM)

• Labor dystocia: prolonged labor and repeated vaginal examinations

• Use of immunosuppressive drugs (eg, steroids for preterm labor)

• Interventions, such as urinary catheterization

Consequences of Fever in Pregnancy

Maternal consequences include increased oxygen demand, increased use of antibiotics, increased assisted delivery rate, and increased cesarean delivery rate. Fetal consequences include increased oxygen demand, increased screening for sepsis,3 increased use of prophylactic antibiotics,3 admission to neonatal intensive care with separation from mother,3 and possible increased incidence of hypoxic encephalopathy.3,4

Fetal temperature is dependent on maternal temperature and is commonly 0.5°C higher than maternal.2 If maternal fever is infective in origin, there is the associated risk of vertical transmission of infection from mother to fetus.

INFECTIVE CAUSES OF FEVER

In more developed regions of the world, the incidence of sepsis in the obstetric population is 0.3% to 0.6%.1 The consequences of sepsis should not be underestimated. Failure to recognize the severity of sepsis is a major contributor to poor obstetric management and subsequent mortality. Sepsis has been implicated as the leading cause of direct maternal deaths in the United Kingdom, as demonstrated in Saving Mothers’ Lives (CMACE 2006-2008).5

Obstetric sepsis is a concern not only at term. It can present in early pregnancy following fetal loss, or termination, or in the postpartum period (eg, from infected retained products of conception).

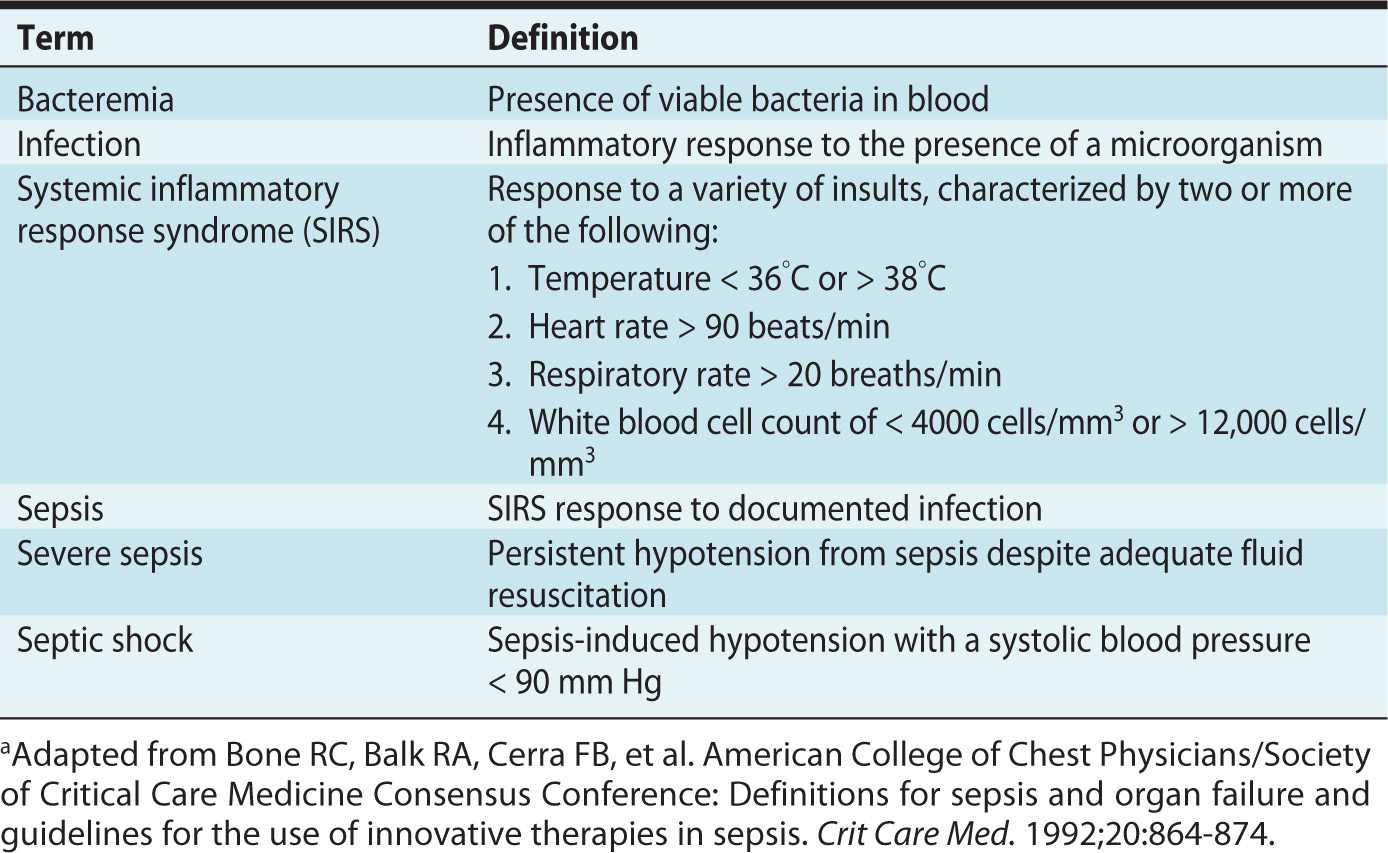

Exact sepsis terminology has been defined to facilitate research and communication between clinicians (Table 18-2). The physiologic changes associated with normal pregnancy (tachypnea and neutrophilia—up to 17,000 cells/mm3 in the third trimester), and the sympathetic response to labor (tachycardia, tachypnea, and increases in temperature secondary to uterine muscle activity) often fulfill the criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (Table 18-2). These factors contribute to the difficulty in assessing severity of illness. Therefore, an obstetric-specific physiologic warning score is recommended to detect early disease and monitor parturients.6 Importantly, sepsis also can present with hypothermia, particularly in those women who have significant immunosuppression.

Table 18-2. Sepsis-Associated Definitionsa

There is a paucity of specific evidence to support management of septic obstetric patients by algorithm, because they are often excluded from randomized controlled trials. Treatment is extrapolated, therefore, from the general population. Early goal-directed therapy aimed at restoring tissue perfusion, broad-spectrum antibiotics commenced within 1 hour of recognition of sepsis (to cover anaerobic as well as gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria), source control and supportive management, are the mainstays of treatment as recommended by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines.7 Care is aimed at maximizing maternal physiology with consideration of fetal viability, depending on gestational age.8 The guiding principle of caring for the sick parturient holds true here as well—optimizing the mother optimizes the fetus. The mother should be stabilized prior to surgery, which takes priority over an emergent cesarean delivery for neonatal indications.

Septic Shock

The definition of septic shock implies evidence of cardiovascular instability, impaired tissue oxygenation, and potential for coagulopathy. Septic shock in the parturient is associated with a relatively favorable prognosis when compared with the general population (less than 20% mortality compared with 30% to 60% in the general population).1 There are multiple reasons to avoid neuraxial anesthesia in this setting as discussed below.

Specific Infections in Pregnancy

CHORIOAMNIONITIS

Chorioamnionitis is the infective inflammation of fetal membranes, commonly the result of bacteria ascending from the vagina. Diagnosis is clinical, and the condition is reported to occur in approximately 1% of all pregnancies.9

For diagnosis of chorioamnionitis,3 a temperature over 38°C is necessary, with two of the following:

• Maternal tachycardia greater than 100 beats/min or fetal tachycardia greater than 160 beats/min for more than 5 minutes

• Uterine tenderness

• Offensive amniotic fluid

• Maternal leukocytosis greater than 16,000 cells/mm3

Chorioamnionitis has an associated increased maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Maternal risks include preterm labor, postpartum hemorrhage, postpartum endometritis, sepsis/severe sepsis/septic shock, pelvic thrombophlebitis, and death. Neonatal risks include pneumonia, meningitis, and increased rates of cerebral palsy.2

Treatment is with broad-spectrum antibiotics. There may be an increased cesarean delivery risk in these patients (46% in one study).10

GROUP B STREPTOCOCCAL INFECTION

Between 10% and 30% of parturients are colonized with group B Streptococcus; it is vertically transmitted at delivery to the fetus.11 The organism can lead to infective complications in mothers (eg, UTI or chorioamnionitis), but of greater importance, it is the most common cause of neonatal infective morbidity and mortality.11 The incidence of group B Streptococcus morbidity is decreasing due to screening (35-37 weeks) and antibiotic prophylaxis.

PARTURIENTS WITH SYSTEMIC INFECTION: IMPLICATIONS FOR ANESTHESIA

Neuraxial Anesthesia

Many anesthesiologists worry that neuraxial needle insertion in bacteremic parturients may cause bleeding and subsequent seeding of bacteria into the epidural or intrathecal space, potentially resulting in an epidural abscess or bacterial meningitis. Transient bacteremias are common in the peripartum period (around 9.9%)1 but, fortunately, infective complications from neuraxial anesthesia are rare.12,13

Decisions concerning analgesic and anesthetic techniques in parturients with fever are based on risk-benefit assessment. Epidural analgesia offers advantages over other methods of labor analgesia, including:

• More effective analgesia

• Reduced stress response to labor in at-risk individuals (eg, a history of cardiac disease)

• An option for rapid conversion to anesthesia for cesarean delivery, thus avoiding the need for general anesthesia

• An option for improved postoperative analgesia

The final anesthetic plan should be made based on an informed discussion with the parturient and on a case-by-case basis. Factors to consider that may influence risk-benefit ratio of epidural analgesia include, the presence of risk factors for neuraxial infective complications (eg, diabetes, human immunodeficiency [HIV] or a history of illicit intravenous drug use), and the presence of factors increasing risks with general anesthesia (eg, morbid obesity, cardiovascular history).

Clinical evaluation of the parturient searching for a potential source of infection and assessing severity of disease is essential. Fever alone may be misleading, because pyrexia and leukocytosis are not predictive of bacteremia in the peripartum period.10 Results of blood cultures will not be available immediately. In practice, most anesthesiologists are conservative about neuraxial procedures and would avoid insertion in parturients with high fever (temperature above 39°C) or those who have not responded to antibiotic therapy (persistent high fever or tachycardia). Presence of septic shock and cardiovascular compromise in the parturient should be considered an absolute contraindication to neuraxial anesthesia.6

Prevention remains the best treatment. The following are recommendations to reduce the risk of developing neuraxial infective complications:

• Strict asepsis for neuraxial procedures14

• Prophylactic antibiotics for at-risk individuals (eg, infective pyrexia, clinical evidence of bacteremia). This approach is supported by a study of lumbar puncture (LP) in bacteremic rats.15

• Methods that improve the success of neuraxial anesthesia (eg, use of epidural ultrasound) may reduce risk because technically difficult insertions, with multiple perforations of the epidural space, result in greater risk of hematoma, potentially increasing the infective complication rate.

• There is evidence suggesting that infective complication rates from combined spinal-epidural anesthesia (CSE) are greater and therefore should be avoided in at-risk individuals. In a large prospective audit that reviewed greater than 700,000 neuraxial procedures, CSEs represented 6% of the blocks performed but accounted for more than 13% of subsequent infective complications. The infective risks associated with spinal and epidural components of the technique appear to be cumulative for causing either bacterial meningitis or epidural abscess.12

EPIDURAL ABSCESS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree