Depression and Bipolar Disorder

Diane M. Snow PhD, RN, CS, CARN, PMHNP

Depression and bipolar disorder (BPD; formerly called manic-depressive disorder) are mood disorders characterized by predominant affective or mood symptoms along with a variety of cognitive and behavioral symptoms. Occurring for specified periods of time, mood disorders cause variable but significant problems in social and occupational functioning. They are prevalent in all age groups and are more commonly diagnosed in women. The majority of suicides occur in persons with serious depression.

Patients with mood disorders are frequently seen in primary care, often presenting with somatic symptoms or coexisting acute or chronic medical illnesses that complicate the clinical picture. Substance abuse, medications, and serious stressors may be precipitating factors. Frequently a family history of depression is reported.

Primary care providers, in a managed care environment, are usually expected to treat depression rather than refer the patient to a psychiatrist. However, depressive illnesses often are underdiagnosed, untreated, and undertreated in primary care settings. Often patients hesitate to discuss symptoms because of embarrassment or fear, or thinking they are there for “physical problems only.” The provider may avoid asking about suicidal ideation despite recognition of depressed mood. Patients with chronic physical illnesses are often not asked about mood and other behaviors indicative of masked depression. Men are rarely asked about depression, as if it is a disease of women only.

Elderly patients are assumed to have dementia when there are any memory or concentration difficulties. Moreover, unless the provider develops adequate rapport with the patient and views the patient “holistically,” the disorder may go undetected. Finally, if the patient is irritable or hostile or shows poor judgment, the provider may dismiss the patient as uncooperative. Adequate treatment and prevention of further episodes are mandatory. Collaborative relationships must be maintained with psychiatric services, and prompt referrals and emergency care must be implemented when warranted. Strategies for prevention include building healthy coping skills, early detection, and relapse prevention, often with help from community resources.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

There are numerous biologic changes that occur in depression and BPD, and they have helped create a new understanding of these painful, often life-threatening disorders. Genetic factors, neuroendocrine, neurotransmission, structural, and functional brain changes are all important aspects of the pathology of depression. Physical illness, medication effects, electrolyte disturbances, and nutritional deficits play an important role as well. Life events such as recent stressors, when combined with genetic factors, are also important (Kendler et al, 1992). More traditional psychological theories support the role of personalities and problem-solving skills in depression and BPD.

Genetics

Family studies have demonstrated that monozygotic twins have a higher rate of concordance (agreement) for depression and BPD than dizygotic twins (Andrews et al, 1990). Family aggregation studies point to the increased risk of depression and BPD in first-degree relatives. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is 1.5 to 3 times more common in first-degree relatives. Rates of BPD exceed those of depression, with a 25% to 27% chance that a child with one parent with BPD will have the disorder (versus 10% to 13% for depression) and a 50% to 75% chance if both parents have bipolar disorder (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994). Moreover, early-onset depression, when symptoms occur as early as childhood, is more familial; patients are likely to have more genetic vulnerability (Overaschel, 1990).

Linkage genetic studies demonstrate that certain chromosomes may show a single gene for certain disorders. Chromosome 11 was first thought to be the genetic marker for BPD, but this was not supported in later studies. More recently, a corticotrophin receptor and a subunit of a G protein on chromosome 18 have been implicated, but this is still under investigation. No single gene has been associated with MDD, probably because of genetic heterogeneity (Berrettini et al, 1994).

Neurobiologic Changes

Neurobiologic changes in mood disorders primarily involve dysfunction of the limbic system, the basal ganglia, and the hypothalamus. The limbic system, specifically the amygdala, modulates emotions, whereas the hippocampus is implicated in memory and concentration difficulties. Changes in the basal ganglia involve motor changes such as stooped posture, motor slowness, and cognitive impairment. Dysfunction of the hypothalamus involves three axes: the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid axis, and the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis.

Dysregulation of several neurotransmitter systems has been found in depression and BPD. Neurotransmitters are molecules that carry messages between neurons. They are released into the synaptic cleft from the presynaptic neuron. From here, they either occupy a receptor site on the postsynaptic membrane of the target neuron or are stored or metabolized by the presynaptic neuron (Restak, 1988). The biogenic amines, particularly serotonin (5HT) and norepinephrine, interact and modulate a variety of functions, such as cognitive, sexual, motor, neuroendocrine,

mood, and sleep, and have been found to be abnormally regulated in depression.

mood, and sleep, and have been found to be abnormally regulated in depression.

Serotonin, whose precursor is the dietary amino acid tryptophan, originates in the raphe nuclei of the pons and upper brain stem and travels widely throughout the brain and spinal cord. Serotonin depletion may precipitate depression; receptor sensitivity increases during a depressive episode, and modulation with other neurotransmitters may be out of balance. Serotonin’s major metabolite, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5H1AA), was lower than normal in a study of depressed persons who committed suicide (Goodwin & Jamison, 1990). Serotonin dysregulation, then, may be related to suicide, impulsivity, and aggressive behavior.

Depletion of norepinephrine is shown in most, but not all, depressed persons. Norepinephrine, whose precursor is the dietary amino acid tyrosine, is produced in the locus ceruleus and projects through six noradrenergic tracts through various parts of the brain. Dopamine levels are believed to increase in mania and decrease in depression. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitter, and acetylcholine (ACTH) also are dysregulated in depression. In BPD, excessive baseline calcium may contribute to a mixture of symptoms as a compensatory response (Dubovsky et al, 1992).

Neuroendocrine changes in the HPA axis include consistent findings of elevated cortisol secretion from the adrenal glands associated with the stress response. Levels of corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF), the hypothalamic peptide that regulates pituitary secretion of corticotrophin, and cortisol have been found to be elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of depressed persons (Nemeroff et al, 1984). CRF release depends on neurotransmitters such as serotonin, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, and GABA (Beeber, 1996). Corticotrophin, by attaching to cells in the adrenal cortex, causes the release of cortisol. In a feedback loop, cortisol then inhibits the secretion of corticotrophin in the anterior pituitary and CRF in the hypothalamus. Increased CRF levels, therefore, may explain the hypercortisolism and HPA axis overactivity seen in MDD. Elevated CRF levels in depression normalize after electroconvulsive therapy and after treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medications (SSRIs).

Levels of somastatin, a growth hormone release inhibitor hormone, decrease in both MDD and depressive episodes of BPD (Rubinow et al, 1983); in manic episodes, this change has not been documented. Along with hypercortisolemia, somastatin underactivity is a consistent finding in depression.

Hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid axis changes frequently occur with depression and BPD. In 25% of people with depression, there is blunting of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) response to thyroid-releasing hormone in the thyroid-releasing hormone stimulation test (Nemeroff, 1990). Elevation of thyroxin, or T4, may be significant in severely depressed patients. Moreover, there are some indications that in postpartum women and women with rapid-cycling BPD (four or more episodes a year), there are thyroid changes that may precipitate bipolar episodes. Lastly, thyroid hormone replacement is used to augment antidepressant therapy in MDD and is sometimes used in rapid-cycling BPD.

Biologic Rhythm Changes

Sleep alterations frequently occur in both depressive and manic episodes; both insomnia and hypersomnia reflect circadian rhythm dysregulation. Sleep problems may include many if not all of the following: delayed sleep onset, shortened rapid eye movement (REM) latency (the time before falling asleep and the first REM period), increased length of first REM period, increased frequency of eye movements during REM sleep, increased spontaneous awakenings, and abnormal delta sleep. Sleep electroencephalographic recordings are abnormal in many depressed persons even before the onset of clinical depression (Giles et al, 1989). This finding may explain why depressed persons report feeling tired even after a night’s sleep. Antidepressant medications are helpful in resetting sleep circadian rhythms.

Additional biologic rhythm disturbances are seen in depression that has seasonal variation, rapid-cycling BPD, and premenstrual mood changes. More common is seasonal depression that recurs in the fall and winter, although some persons have a reverse pattern of depression in the spring and summer. Thought to be related to the changes in light and temperature, seasonal depression is currently being treated or “reset” with phototherapy or light therapy. Rapid-cycling BPD involves rapidly switching to mania or depression in rhythmic cycles that may be days, weeks, or months long. Many women note increased mood variations based on the biologic rhythm and hormonal changes during their menstrual cycles.

Electrophysiologic Process of Kindling

A recent advance in understanding the nature of relapse in depression and BPD has been through the phenomenon of “kindling,” or sensitization. Repeated subthreshold stimulation of neurons in seizure disorders eventually can precipitate a seizure, and the same electrophysiologic process is believed to occur with depression and BPD (Keltner et al, 1998). Kindling in the temporal lobes, possibly based on genetic predisposition, causes a return of symptoms, even more so if there has been inadequate treatment. Each subsequent episode tends to have worse symptoms, and episodes occur closer together.

Although earlier episodes often require triggering from external stimulation, later episodes kindle by repetition and become an autonomous process. Continued prophylactic pharmacotherapy after the reduction or elimination of symptoms will help prevent chronicity and worsening of symptoms. Particularly useful for prophylaxis of BPD are the anticonvulsant medications used as mood stabilizers (carbamazepine, valproax sodium, lamotrigine, and gabapentin).

Structural and Functional Brain Changes

Structural changes in the brain, interpreted in neuroimaging studies using magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, include decreased size of the caudate nuclei and putamen of the basal ganglia and decreased prefrontal cortex volume. There are abnormal hippocampal times in magnetic resonance imaging T1 images, which are short-time sequences used to define the brain and spinal cord anatomy. The hippocampus is the major area of the limbic system for memory and learning. Temporal lobe volume is reduced and there are deep white matter lesions in BPD. Changes in the orbitofrontal cortex during a manic episode are probably responsible for the impulsivity, social inhibition, and lability of mood of these periods (Cummings, 1993).

Cerebral blood flow and metabolism are measures of brain function that are seen in photon emission tomography and

single photon emission computed tomography. Decreased cerebral blood flow and hypometabolism in the frontal cortex, where logical thought and reasoning occur, have been consistent findings in depression (Keltner et al, 1998). Increased metabolic activity, as well as cerebral asymmetries indicating hypometabolism limited to the left frontal lobe, have been found in these scans in patients with BPD. Also, abnormal regulation of phospholipid metabolism has been found in BPD patients.

single photon emission computed tomography. Decreased cerebral blood flow and hypometabolism in the frontal cortex, where logical thought and reasoning occur, have been consistent findings in depression (Keltner et al, 1998). Increased metabolic activity, as well as cerebral asymmetries indicating hypometabolism limited to the left frontal lobe, have been found in these scans in patients with BPD. Also, abnormal regulation of phospholipid metabolism has been found in BPD patients.

Physical Illness and Depression

Certain physical illnesses that involve the same brain structures that are altered in depression will cause symptoms of depression. For example, in Huntington’s disease there is a high rate of depression, based on the reduction of volume in the putamen and caudate nuclei. In cerebrovascular accidents that involve the frontal and temporal lobes, manic symptoms are more common with right-sided lesions, whereas depressive symptoms are more common with left-sided lesions (Keltner et al, 1998).

Psychological Theories

Psychological theories of depression include the psychoanalytic explanation of depression as anger directed internally, based on the introjection of an ambivalently held lost object. Early attachment difficulties, based on the impact of separation and loss, may precipitate depression (Bowlby, 1980). Behavioral theory views vulnerability to depression as a lack of social support, causing loneliness and isolation (Skinner, 1953). Inadequate social skills that prevent positive reinforcement from others contribute to depression under this model (Lewinsohn, 1974). Cognitive theory proposes that depression is precipitated and maintained by negative thoughts and attitudes; a cognitive triad of negative views of self, others, and the future; and negative schemas or belief systems (Beck, 1976).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Depression and BPD are serious mental health problems that must be addressed in primary care. MDD affects 15% of the population, with prevalence rates as high as 25% in women (APA, 1994). The National Institute of Health estimates that 15 million Americans become depressed in any given year (Hall & Wise, 1995). It is estimated that 1 in 5 women and 1 in 10 men seen in primary care have recently been depressed (Rowe et al, 1995). The rate may be even higher (12% to 36%) when the person has a general medical condition (Depression Guideline Panel, 1993a).

Women suffer depression at a rate twice that of men, and younger women are at greater risk than any other age group (Depression Guideline Panel, 1993a). Particular points of vulnerability for depression in women are rhythm-disrupting events such as the perinatal, menopausal, and menstrual periods and seasonal light changes (Beeber, 1996). Treatment may involve restoration of normal rhythms through endocrine treatment and phototherapy.

Depression and BPD are found in all cultures. Cultural expressions of symptoms vary and should be considered during all aspects of care. True psychosis must be distinguished from culturally specific experiences. Treatment choices must be sensitive to the cultural needs of patients.

Increased rates of alcoholism are seen in adult first-degree relatives of persons with MDD; the incidence of ADHD is also increased in children of adults with MDD (APA, 1994).

In older adults, the rate of depression seen in primary care is 5%; the rate seen in long-term care facilities is 15% to 25% (NIH, 1992). A study of long-term care patients found that the presence of MDD raised the risk of rapid death by 59% (Rover et al, 1991).

The lifetime rate of dysthymic disorder has been found to be 4.1% for women and 2.2% for men. The diagnosis of depression not otherwise specified has a point prevalence of 8.4% to 9.7% in primary care patients (Depression Guideline Panel, 1993a).

Suicide is the eighth leading cause of death among all age groups, and at least 50% of suicides can be attributed to MDD. For persons aged 15 to 24, suicide is the third leading cause of death. More than 70% of all suicides in the United States are committed by white men. Suicide rates are alarmingly high in very old men, with 75.1 suicides per 100,000 population versus an overall suicide rate of 11.8 per 100,000. The group at highest risk for suicide is elderly American men (Moscicki, 1995). (See Table 60-5.)

BPD type I disorder has a lifetime risk of close to 1%, with approximately equal gender distribution and no association with race or ethnic origin. Combining types I and II, there is a 1.2% lifetime prevalence rate (Regier et al, 1990). Interestingly, in men the first episode is more likely to be a manic episode, whereas in women the first episode is more likely to be a major depressive episode. Women with type I have an increased risk for further episodes postpartum. First-degree biologic relatives have 4% to 24% higher rates of type I (APA, 1994).

Cyclothymic disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 0.4% to 1% (Depression Guideline Panel, 1993a).

BPD in children and adolescents, although underdiagnosed, is considered to occur at least as frequently as in adults (Geller & Luby, 1997). Comorbidity includes ADHD, conduct disorder, substance abuse, and anxiety disorders.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Screening, assessment, accurate diagnosis, adequate treatment, frequent follow-up, and referrals for psychotherapy and psychiatric evaluation (if needed) are critical for patients with symptoms of depression and BPD. Any patient with a history of depression or BPD needs to be assessed on a regular basis for treatment response, side effects, new symptoms, and recurrence of symptoms. Patients need encouragement to obtain and continue treatment. Providers need a thorough understanding of the diagnostic categories and the complexity and variability of depressive symptoms. Widely available self-report screening tools for depression that are useful for measuring treatment response include the Beck Depression Inventory, Zung Depression and Anxiety Scales, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, and Geriatric Depression Scale. The Symptoms-Driven Diagnostic System for Primary Care (SIDDS-PC) is a computer-based tool; the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale are provider-rated tools that are completed during the interview.

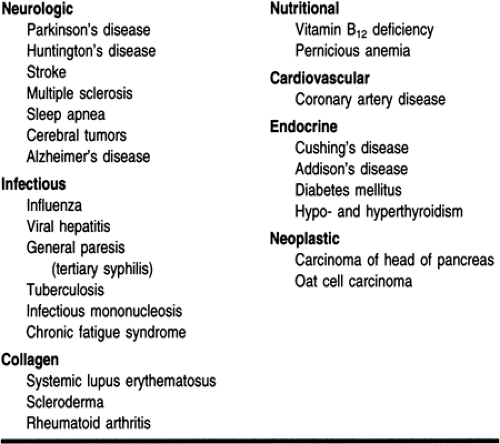

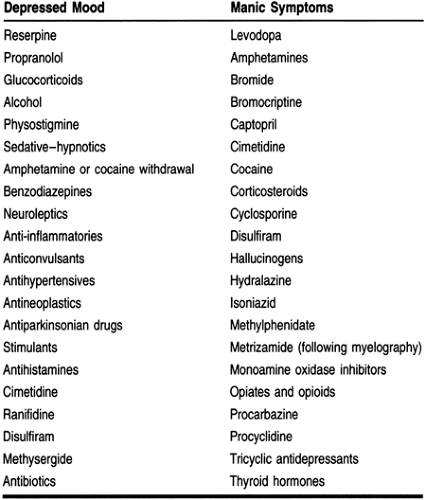

Next, the history and clinical interview address target symptoms from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV; APA, 1994), including age, gender, family system, and cultural considerations. The results of the screening tools, mental status exam, laboratory values, and physical exam will help determine the presence of depression or BPD. Medical illnesses and medications that may precipitate depression must also be evaluated (Tables 60-1 and 60-2).

Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV; APA, 1994), including age, gender, family system, and cultural considerations. The results of the screening tools, mental status exam, laboratory values, and physical exam will help determine the presence of depression or BPD. Medical illnesses and medications that may precipitate depression must also be evaluated (Tables 60-1 and 60-2).

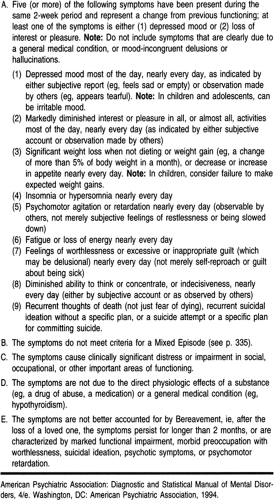

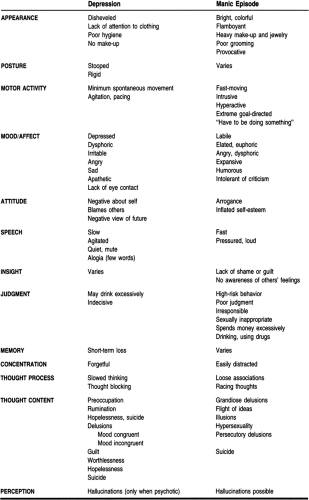

Major Depressive Disorder

MDD, or unipolar depression, is the most frequently diagnosed mood-related disorder. It signifies there has been at least one major depressive episode and no manic or hypomanic episodes. Symptoms have occurred every day for 2 weeks or longer. Significant distress or impairment in psychosocial or work functioning must be present. For a diagnosis of MDD to be made, substance use, medication, and medical conditions must be ruled out. A mood disturbance must be present with a number of alterations from normal mood (eg, depressed mood with typical sadness, agitation and anger, irritability, dysphoria, numbing of feelings, or somatic preoccupation). Of equal importance is the loss of pleasure in activities that were previously enjoyed, such as hobbies, work, or sexual activity. One of these two symptoms—mood disturbance or loss of pleasure—must be present for a diagnosis of MDD.

Additional symptoms must also be present. Three neurovegetative symptoms are evaluated: sleep, appetite, and psychomotor activity. Sleep alteration may be present (insomnia or hypersomnia). Insomnia can take the form of difficulty falling asleep (initial insomnia), frequent waking without being able to fall back to sleep quickly (middle insomnia), or waking several hours earlier than usual (terminal insomnia). Hypersomnia means the person sleeps several more hours a day than is usual for that person. A key concern is whether the person feels rested after a night’s sleep. Psychomotor activity may be observed as either very sluggish, slow movements or agitation or pacing, where the person cannot stop moving. An increase or decrease in appetite or weight gain or loss of 5% or more of body weight must be assessed.

Other evaluated symptoms include a feeling of fatigue or loss of energy, expressed as a loss of will. Also, feelings of worthlessness and guilt are common, sometimes manifested in psychotic delusions. Difficulty with concentration, thinking, or making decisions is distressing. A patient may forget to bathe or change clothes or complain of not being able to complete tasks. In the older person, memory loss may appear to be dementia when in fact it is pseudodementia or memory loss caused by depression.

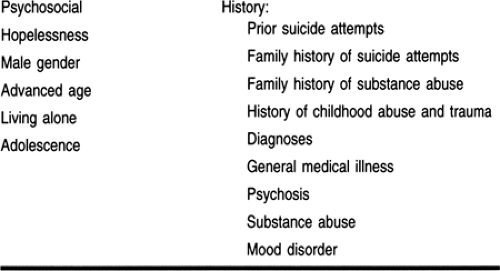

Suicidality is an extremely serious symptom of MDD and must be assessed in anyone who has mood alteration. Hopelessness and thoughts of death without specific suicidal thoughts (eg, “Death would be such a relief; why go on?”). More serious are suicidal thoughts or ideation (eg, “I keep thinking that everyone would be better off without me”), while some persons have made actual suicide attempts. Asking the patient about suicidal thoughts will not cause the person to become suicidal. Frequency of thoughts, presence of a plan, methods, previous attempts, and history of suicide in the family are important assessment factors (Table 60-3).

There are subtypes of MDD that delineate the severity and type of depression. These include mild, moderate, and severe, referring to the severity of impairment in functioning; psychosis with hallucinations or delusions, catatonic features, melancholic features, and atypical features are other specifiers.

The onset of MDD in the postpartum period (within 4 weeks of delivery), with symptoms that last 2 to 12 months after delivery, is a specifier and is likely to recur with later deliveries. Guilt is a major component of this type of depression.

Seasonal pattern delineation is made when there is a 2-year pattern of recurrence during the winter (or, more rarely, during

the summer). Characteristics are weight gain, low energy, hypersomnia, and carbohydrate craving. Remission requires 2 months without symptoms.

the summer). Characteristics are weight gain, low energy, hypersomnia, and carbohydrate craving. Remission requires 2 months without symptoms.

Dysthymic disorder is a chronic milder form of depression that lasts 2 years in adults and 1 year in children and adolescents. Two or more of the following must be present: poor appetite or overeating; insomnia or hypersomnia; low energy or fatigue; low self-esteem; poor concentration or difficulty making decisions; and feelings of hopelessness.

Adjustment disorder with depressed mood is a direct result of a designated stressor occurring within 3 months; as such, the cause must be identified. The distress is more than would be expected and causes significant impairment in functioning.

Depressive disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) refers to depressed persons who do not meet the criteria for MDD, dysthymia, or adjustment disorder with depressed mood. Included are premenstrual dysphoric disorder, which occurs each month, 1 or 2 weeks before the onset of menses, and has the same symptoms as MDD. Symptoms completely remit when menses begins.

Bipolar Disorders

BPDs are defined by the presence of depressive and manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree