Dementia and Delirium

Joseph Scarpa MD, CMD

Peter Sanna PA-C, MPH

Dementia, a syndrome of deterioration of cognition in alert persons that results in their impaired performance of activities of daily living (Fleming et al, 1995), is difficult to recognize, especially in the early stages, as evidenced by the failure of clinicians to detect this disease in 21% to 72% of patients who have it (Pinholt et al, 1987; Fleming et al, 1995). The importance of early recognition cannot be emphasized strongly enough because with early recognition and aggressive management, the outcome for reversible disease may be improved, and incurable dementias may be better managed (Fleming et al, 1995).

The cost of caring for persons with dementia is high: according to Ernst and Hay (1994), direct costs of Alzheimer’s disease (separate from other dementing illnesses) in the United States in 1991 were an estimated $20.6 billion, and unpaid caregiver costs were an estimated $33.3 billion.

Dementia and delirium were previously thought to be related, but now it is well established that these are, indeed, two separate disease entities. Delirium, also known as acute confusional state, is a transient disorder involving cognitive impairment with attentional deficit resulting in behavioral phenomena; like dementia, it is frequently misdiagnosed (Caine et al, 1995). Delirium is discussed in the second part of this chapter.

Dementia is distinguished from delirium because dementia is an acquired loss of or impairment in intellectual function whose nature is persistent and stable, whereas delirium is associated with altered consciousness, fluctuating deficits, and usually rapid onset (Caine et al, 1995).

Because of the vast body of literature in this field, the references used for this article were mainly recent, comprehensive review articles addressing the various subtopics presented below. The interested reader may wish to gather further, more detailed information from the references cited.

DEMENTIA

Dementia is an acquired loss of multiple cognitive functions and is usually, but not always, progressive, resulting in the deterioration of social, occupational, and functional abilities. At least two domains of intellectual function are affected: one is memory, and the other may be language, perception, visuospatial function, calculation, judgment, abstraction, and problem-solving skills. Patients may present with the full array of psychiatric symptoms (Caine et al, 1995; Fleming et al, 1995).

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

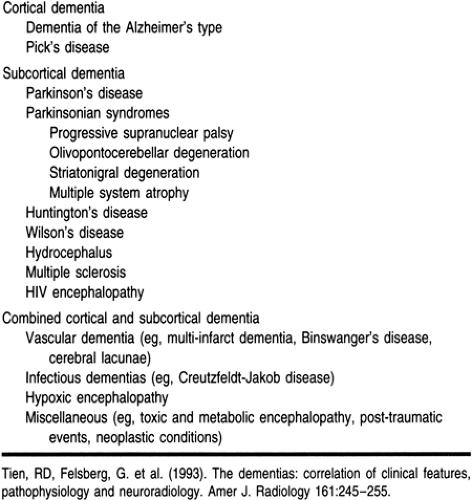

One useful scheme of classifying the dementias is by the structures involved, because each dementia is associated with a typical pattern of neuropsychological deficits correlated with specific brain sites (Tien et al, 1993). The three major categories of dementias are cortical, subcortical, and mixed (Table 51-1).

CORTICAL DEMENTIA

Cortical dementia affects predominantly the cerebral cortex and includes dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) and Pick’s disease. The clinical correlates include agnosia, apraxia, aphasia, amnesia, abnormal cognition, and abnormal affect (classically, disinhibition); the motor system is unaffected (Tien et al, 1993).

Pathologic studies of brains of patients with DAT reveal diffuse atrophy of the brain, with widespread loss of neurons, especially in the temporal, parietal, and anterior frontal lobe cortices. The degree of atrophy tends to correspond to the clinical stage of DAT. Microscopic studies show neurofibrillary tangles, senile plaques, and granulovacuolar degeneration, usually in the pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus. A definitive diagnosis can be made only at autopsy or on cerebral biopsy (Tien et al, 1993).

In Pick’s disease, which is 10 to 15 times less common than DAT, cortical lobar atrophy is highly focal, usually affecting the frontal and temporal lobes (both in approximately 50% of cases, and approximately evenly divided between the two in the rest of the cases). Histopathologic studies reveal intracytoplasmic Pick bodies (composed of neural filaments and tubules) and neuronal loss accompanied by cortical and subcortical gliosis (Tien et al, 1993).

SUBCORTICAL DEMENTIA

Subcortical dementia is caused by diseases that produce dysfunction in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brain stem. It includes extrapyramidal syndromes, hydrocephalus, and white matter disease. Clinical manifestations include not only forgetfulness, slowing of cognition, and abnormal affect (classically, depression), but also motor symptoms such as disorders of posture, increased tone with tremors or dystonia, and gait disturbance (Tien et al, 1993).

Parkinson’s Disease

Dementia is identified in 20% to 90% of patients with Parkinson’s disease, a disease that affects approximately 1% of the population over age 50. Subcortical dementia of this type is

associated with a reduction of pigmented cells of the substantia nigra, which results in malfunction of the efferent nigrostriatal tract; this loss of nigral input to the striatal dopamine receptors further results in disruption of normal coordination of basal ganglionic activity. The interruption of dopaminergic pathways from the ventral tegmentum to the frontal lobe may cause the clinically identifiable cognitive abnormalities. The remaining neuronal cells may contain eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions called Lewy bodies (Tien et al, 1993).

associated with a reduction of pigmented cells of the substantia nigra, which results in malfunction of the efferent nigrostriatal tract; this loss of nigral input to the striatal dopamine receptors further results in disruption of normal coordination of basal ganglionic activity. The interruption of dopaminergic pathways from the ventral tegmentum to the frontal lobe may cause the clinically identifiable cognitive abnormalities. The remaining neuronal cells may contain eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions called Lewy bodies (Tien et al, 1993).

Parkinsonian Syndromes

Patients with parkinsonian syndromes (including progressive supranuclear palsy, striatonigral degeneration, multiple system atrophy, Shy-Drager syndrome, and olivopontocerebellar atrophy) may show typical subcortical dementia, including forgetfulness, slowness of thought, and personality changes, usually with depression, but they may also have varied clinical presentations, depending on the specific disease. Patients with parkinsonian syndromes respond poorly to antiparkinsonian therapy, a feature that may be used diagnostically (Tien et al, 1993).

One of the main pathologic differences between patients with Parkinson’s disease and patients with parkinsonian syndromes is the presence of striatal nerve cell degeneration in the latter. The dopamine content of the striatum and substantia nigra is decreased, and there is degeneration of cells in the putamen and pars compacta of the substantia nigra—this is associated with rigid bradykinesia. Degeneration of cells in the intermediolateral columns of the spinal cord is associated with progressive autonomic failure, and degeneration of cells in the inferior olivary and pontine nuclei and of cerebellar Purkinje cells is associated with olivopontocerebellar atrophy. The cerebral cortex seems to be histologically and anatomically unaffected (Tien et al, 1993).

Other Subcortical Dementias

Huntington’s disease, Wilson’s disease, hydrocephalus, multiple sclerosis, and HIV encephalopathy are also considered underlying causes of subcortical dementias.

The pathologic changes associated with Huntington’s disease are gross atrophy of the head of the caudate nucleus, with less severe changes in the putamen and globus pallidus. Histologically, neuronal loss and gliosis in the caudate nucleus, putamen, and globus pallidus can be observed (Tien et al, 1993).

Wilson’s disease (hepatolenticular degeneration), resulting from a genetic inability to synthesize ceruloplasmin, is associated with pathologic evidence of atrophy, gliosis, edema, and occasionally necrosis in the lentiform nuclei (globus pallidus and putamen) (Tien et al, 1993).

Hydrocephalus is an uncommon cause of dementia, and can be corrected with resultant reversal of intellectual deficits. Dilation of the ventricular system is the main pathologic feature (Tien et al, 1993).

Multiple sclerosis is associated with multiple scattered lesions (plaques) involving the white matter—especially subependymal veins in the periventricular white matter, although the distribution of the plaques in the white matter could be random—but not the subcortical U fibers, cortex, and deep gray matter.

HIV encephalopathy is the most common infection-related dementia and the most common cause of dementia in young adults (excluding trauma). It is associated with multinucleated giant cells in the white matter and, to a lesser extent, the gray matter. Demyelination can be seen on neuroimaging (Tien et al, 1993).

MIXED DEMENTIA

Mixed dementia includes conditions involving both cortical and subcortical structures; vascular dementia and infectious dementia are included in this category (Tien et al, 1993).

Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia includes syndromes of mental insufficiency related to multiple infarcts, small single strategically placed infarcts, posthemorrhagic states, and ischemic states not necessarily resulting in infarction. The vessels involved determine the signs and symptoms. Multi-infarct dementia, subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy or Binswanger’s disease, and cerebral lacunae are the main vascular dementia syndromes. Of patients with vascular dementia, approximately 20% have cortical infarcts, approximately 70% have lacunar infarcts, approximately 60% to 100% have small-vessel ischemia, and approximately 30% have a mixture (Tien et al, 1993).

In the brains of patients with Binswanger’s disease, demyelination, axonal loss, and hyalinoid thickening of small artery walls in the deep white matter can be observed (Tien et al, 1993).

Cerebral lacunae result from lesions of the lenticulostriate and thalamoperforating arteries (which show arterial disorganization and fibrinoid destruction), and refer to the presence of multiple, small, deep, focal infarcts in the deep gray matter and internal capsule (Tien et al, 1993).

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

In Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, there is diffuse cerebral atrophy with no evidence of inflammation. Neuronal loss and gliosis are widespread, accompanied by spongiform change (Tien et al, 1993).

Hypoxic Encephalopathy

Neuronal loss can be observed after both acute and chronic cerebral hypoxia; if acute, neuronal injury tends to be focal and of a characteristic pattern visible on neuroimaging.

DEMENTIA WITH LEWY BODIES

Recently, another category of dementia has been recognized: dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuropathologic autopsy studies found that 15% to 25% of elderly demented patients have Lewy bodies in their brain stem and cortex, possibly making this the second most common pathologic subgroup among the dementias (after Alzheimer’s disease) (McKeith et al, 1996). Patients with dementia with Lewy bodies tend to have rapidly progressing clinical symptoms, especially attentional impairments, problem-solving difficulties, and visuospatial impairments. Persistent visual hallucinations and spontaneous motor features of parkinsonism are hallmarks of the early development of this disease.

The identification of the specific cause of dementia is important in improving both the treatment and the prognosis of the patient.

Epidemiology

Dementia affects 3% to 11% of community-dwelling older adults over 65 years of age (severe in 5%, mild in 10% [Andreasen & Black, 1995]), but the prevalence in persons over 80 is 20% to 50%, with lower rates among community dwellers and higher rates among hospitalized and institutionalized patients. Almost 60% of people over 100 years of age are reported to have dementia (Fleming et al, 1995; Andreasen & Black, 1995).

Although more than 60 causes of dementia have been identified, DAT accounts for approximately 50% to 60% of cases (Tien et al, 1993) and affects approximately 2.5 million Americans (Andreasen & Black, 1995). It is the most common dementing disorder in North America, Scandinavia, and Europe (Caine et al, 1995). In Japan and Russia, however, vascular dementia is the more common type (Caine et al, 1995). Among persons over 75, the risk for DAT is six times greater than for vascular dementia (Caine et al, 1995).

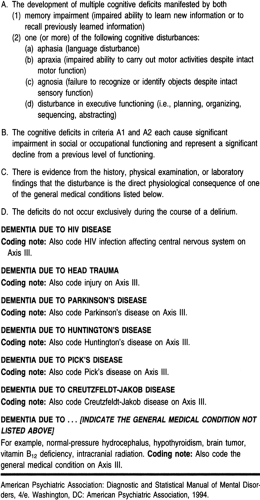

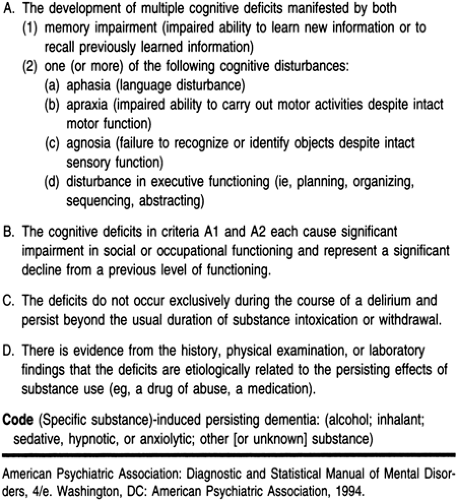

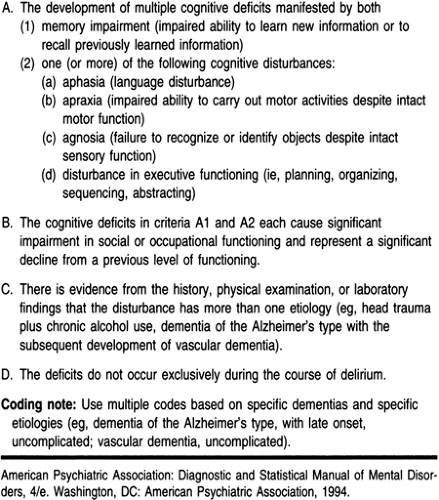

Diagnostic Criteria

Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease include those that are definite, such as old age, Down syndrome, family history, ApoE genotype 4; those that are less definite, such as female, history of head injury, Down syndrome in the family, and vascular risk factors; and those that are least definite, such as aluminum and herpes simplex virus I (Writing Committee, 1996; Eastwood, 1997). “Protective factors” include ApoE 2 genotype, high IQ or educational achievement, postmenopausal estrogen use, and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Eastwood, 1997).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree