Connective Tissue Disorders

Naomi Schlesinger M.D.

The connective tissue diseases, also called collagen vascular diseases, are a group of multisystemic diseases. They include but are not limited to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and the vasculitides. These diseases are characterized by pathologic changes in the blood vessels and connective tissues. The connective tissue diseases are autoimmune diseases. The basic cause of the defective immunity is uncertain but most likely involves an interaction between genetic factors and environmental agents.

Diagnosing these diseases definitively is often difficult because many patients fulfill only part of the diagnostic criteria. Further, many of these diseases overlap, making diagnosis difficult. However, in many of the connective tissue disorders, the affected target organs may be different. In scleroderma, typical skin findings may be noted, whereas in Sjögren’s, the lacrimal glands and salivary glands are the prime targets. Most have musculoskeletal involvement as an important feature of the disease.

Inflammatory connective tissue diseases respond to corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive medications. Although clinical response to corticosteroids is usually the rule in SLE or the vasculitides, it is not so with scleroderma. Through knowledge of the common and the unique clinical features, immunologic mechanisms, organ involvement, and the response to treatment, providers can have a better understanding of the connective tissue diseases.

The provider–patient relationship is essential with any disease. Given the multisystemic nature of the connective tissue disorders, almost any organ may be affected. Providers need to treat the disease, but they must also understand the impact of the disease on the patient and the family as a whole. Patients need to be educated about sequelae and prognosis. Depending on the severity of the disease, connective tissue disorders affect every aspect of life, including planning a family, raising a family, employment, and even ability to perform daily activities. Continual counseling must occur, and often it is the primary provider who does this.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE is the most common of the connective tissue diseases. It is a multisystemic disease with a wide variety of clinical manifestations, ranging from a benign, easily treated disease with a rash and arthritis to a life-threatening illness with progressive nephritis or central nervous system damage. SLE is characterized by exacerbations and remissions.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

SLE is characterized by excessive autoantibody production, immune complex formation, and immunologically mediated tissue injury. The pathologic findings of SLE occur throughout the body and are manifested by inflammation and blood vessel abnormalities. This is noted as bland vasculopathy and vasculitis as well as immune complex deposition.

Hematoxylin bodies, also known as LE bodies, containing both DNA and immunoglobulin are highly suggestive of SLE (Godman & Deitch, 1957). They can be found in any organ but are more commonly found in glomeruli and the endocardium. LE cells are phagocytes that engulf these bodies.

Different organs have various histologic findings in SLE. Some findings are pathognomonic for SLE, whereas others are not specific at all. The pathology of the kidney has been studied extensively because renal biopsies are commonly performed to assess the disease activity. The kidney in SLE displays varying degrees of inflammation, increased mesangial cells and matrix, cellular proliferation, basement membrane abnormalities, and immune complex deposition. Skin lesions in SLE show inflammation and degeneration at the dermal–epidermal junction. Complement components and immunoglobulins can be demonstrated in a band-like pattern by immunofluorescence microscopy. Concentric periarterial fibrosis or onion-skin changes in the spleen are considered pathognomonic for SLE.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of SLE varies throughout the world. Its prevalence in the United States has been estimated in the range of 15 to 50 per 100,000. It is more prevalent in women (female/male ratio of 9:1), particularly those in their reproductive years. The disease may affect as many as 1 in 1000 young women. Initial presentation is usually between the first and fourth decade. Approximately 10% of SLE patients present after the age of 60. The prognosis for men (Miller et al, 1983) and children (Barron et al, 1993) with SLE is less favorable than it is for women. SLE that begins after the age of 60 (in both sexes) tends to have a more benign course; arthritis, pleurisy, rash, and anemia are the major manifestations (Baker et al, 1979).

In the United States, SLE is more common among African Americans and Hispanics than whites. The average incidence in the United States is 25.5 per 1 million population for white females and 75.4 per 1 million for African American females. African American patients with SLE have also been shown to have anti-Smith antibody and antiribonucleoprotein antibody, discoid skin lesions, cellular casts, and serositis more commonly (Ward & Studenski, 1990). They have also been considered to have a poorer prognosis than white patients (Reveille et al, 1990). Patients with a lower education level, which may reflect a lower socioeconomic status, do less well than those with a higher education level (Callahan & Pincus, 1990).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

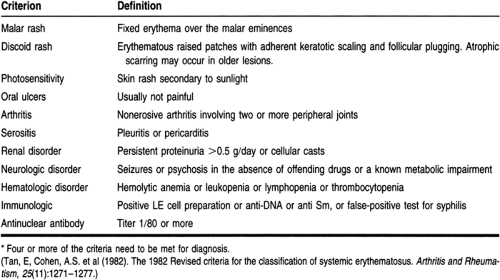

Table 40-1 lists the manifestations of SLE (Tan et al, 1982). Signs and symptoms of almost all the organ systems are included, in addition to distinct laboratory findings. The presence of four or more of these manifestations is the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for diagnosing SLE. The ACR criteria help distinguish patients with SLE from patients with other connective tissue diseases but are not helpful in assessing the severity or prognosis of the disease. Further, there may be times when not all the diagnostic criteria are met, but clinical suspicion for SLE remains high.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

The most important part of the examination of the patient suspected of having SLE is the history. The patient must be asked about systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and weight loss; musculoskeletal complaints such as arthritis and arthralgia, myalgias; cardiopulmonary complaints such as chest pain and shortness of breath; cutaneous lesions including alopecia, rash, photosensitivity, and oral or nasal ulcers; and nervous system complaints such as headaches and migraines, psychosis, depression, and seizures. The family history is very important because 10% to 15% of patients have a first-degree relative with SLE and 18% to 22% of patients have a relative with SLE (Pistiner et al, 1990; Hull, 1975).

The exam of the patient should not be limited to the skin or the musculoskeletal system; attention should be paid to all the other organ systems that may be involved. The exam should begin with vital signs, including temperature, respirations, pulse, blood pressure, and weight. Weight loss is often noted through serial evaluations. The skin (including mucosal surfaces), hair, and scalp are usually examined first. A thorough pulmonary and cardiac exam is required, as is a careful neurologic exam.

Musculoskeletal features: Arthralgia or arthritis is a presenting manifestation of 95% of patients with SLE (Cronin, 1988). The acute arthritis may involve any joint but typically involves the small joints of the hands, wrists, and knees. It is characteristically episodic, oligoarticular, and migratory; unlike rheumatoid arthritis, it is not destructive. Radiographic findings, therefore, are usually minimal. Myalgia and generalized muscle tenderness occur frequently during exacerbations of the disease: they are observed in up to 80% of patients. Tendinitis is also common and can result in tendon rupture (Furie & Chartash, 1988).

Cutaneous manifestations: Skin lesions seen can be divided into acute lesions, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and chronic lupus. The classic “butterfly” malar rash over the cheeks and the bridge of the nose is the acute lesion. It is present from days to weeks and is often pruritic or painful. Commonly precipitated by sunlight, it occurs in only one third of SLE patients. A patchy rash on the upper trunk and sun-exposed areas (photosensitivity) is more common (Callan, 1988). Subcutaneous lupus erythematosus refers to a cutaneous lesion that is nonscaring, is papulosquamous or annular (or both), and has LE-specific histopathology. It is present on the trunk, limbs, face, and palms. Most patients with this type of rash have antibodies to the Ro (SS-A) antigen. Discoid lesions are chronic lesions. Patients with skin lesions of discoid lupus

may or may not have evidence of SLE. In general, when other features of SLE are present, the course tends to be more indolent in patients with discoid lupus (Prystowsky et al, 1976). In addition, the oropharyngeal and nasal mucosa may reveal painless ulcerations.

Renal disease: Specific symptoms are not voiced by patients until they have advanced nephrotic syndrome or renal failure. Clinically, renal disease is reported in about 50% of patients during the first year of the clinical diagnosis of SLE. The prevalence seems to increase in subsequent years. Although most patients have some renal lesions (Bennett et al, 1977), severe renal disease that leads to death or the need for renal transplant occurs in only a small percentage (15% to 20%) of patients. A renal biopsy provides the most reliable information about the type and severity of renal involvement. In general, the more severe the glomerular inflammation, the worse the prognosis. The major indications for a renal biopsy are to determine whether irreversible renal disease is present, to investigate atypical renal failure, and to document the subtype and stage of nephritis for study purposes.

Neuropsychiatric manifestations: Neurologic manifestations of SLE (CNS lupus) are present in most SLE patients at some point during the course of their disease. The neurologic manifestations of the disease can affect any part of the central nervous system. Symptoms may include headaches, migraine headaches (Brandt & Lessel, 1978), seizures, strokes, frank psychosis, cognitive dysfunction, and dementia. Up to two thirds of patients with SLE show some cognitive impairment or other signs of CNS lupus. However, it is sometimes difficult to determine if these manifestations are secondary to lupus, treatments for lupus (eg, steroids), or concomitant disease.

Cardiopulmonary manifestations: Although pericarditis is clinically present in up to 45% of patients, pericardial lesions are found in 60% to 80% of the cases at autopsy. The physical exam may reveal a pericardial friction rub, and an electrocardiogram may reveal ST elevations in the precordial leads. Pleuritis, secondary to a pleural effusion, is present in up to 60% of lupus patients during the course of their disease. Attacks of pleuritic pain often last for days to weeks. The pleural effusion generally occurs on the side of the chest pain, and during the physical exam there may be crackles or a decrease in breath sounds over the area of the effusion. When an infiltrate is seen on the chest x-ray, the most common cause is an infection. Lupus pneumonitis is uncommon.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) is a general term used to describe any autoantibodies directed against a component of the nucleus. The detection of an ANA is a sensitive screening test for SLE but is not very specific. ANAs occur in 95% of SLE patients (Hochberg, 1990). The degree of positivity of the ANAs is diagnostically important. The positive predictive value of the test increases with higher titers.

ANAs include antibodies to each of the following: dsDNA (anti-double-stranded DNA), ssDNA (anti-single-stranded DNA), Sm (anti-Smith), RNP (antiribonucleoprotein), SS-A (Ro), SS-B (La), Scl-70, centromere, Jo-1, PM-Scl, histones, enzymes, tRNAs, and structural proteins.

SS-A (anti-Ro) and SS-B (anti-La) antibodies are found in just less than half and nearly a fifth of lupus patients, respectively. SS-A is associated with photosensitive skin rash, interstitial pneumonitis, thrombocytopenia, and nephritis. SS-B is associated with absence of nephritis in SLE. The presence of SS-A and SS-B is associated with congenital heart block, Sjögren’s syndrome, subacute cutaneous lupus, and neonatal lupus dermatitis. Although levels of these antibodies may change, monitoring levels of SS-A or SS-B is not warranted because the relevance to disease expression is not known (Harley & Reichlin, 1993).

Antibodies to double-stranded DNA (found in 30% of patients with inactive disease and in 60% with active disease) and to Smith, a ribonucleoprotein antigen (found in 30% of SLE patients), are more specific than other ANAs for the diagnosis of SLE. The titer of the antibody is a useful measure of disease activity (Ter Borg et al, 1990).

Patients with clinically active SLE have depressed complement levels. Evaluation of the complement system can serve as an indirect measure of the presence of immune complexes. The total hemolytic complement level (CH50) represents the sum of all the components of the system. Separate complement components (C3, C4, and C1q) should also be measured. SLE patients with renal disease tend to have lower mean levels of CH50, C1q, C4, and C3 than those without renal disease (Schur, 1993). Normal C3 and anti-DNA levels usually correlate with improvement in disease activity (Schur, 1993). Following CH50, C3, C4, C1q, and anti-dsDNA antibody levels appears to be most useful in predicting exacerbations of disease and in following therapy.

Antiphospholipid antibodies and anticardiolipin antibodies are found in increased frequency in patients with SLE. They should be sought in patients who have increased thromboembolic events, venous thrombosis, and recurrent spontaneous abortions.

Routine screening of chemistries, complete blood count, and urinalysis need to be included as part of a regular evaluation. Anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia are often present. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate, although nonspecific, is usually elevated in SLE. Patients with worsening disease may need to be seen weekly, but patients with stable SLE need less frequent evaluations.

The principal tests used to follow lupus nephritis are blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, creatinine clearance, 24-hour urine for protein, urinary sediment, C3, and anti-dsDNA antibody. Serum creatinine or creatinine clearance reflects the level of renal function but reveals little about disease activity. Nearly all patients with clinically important renal disease have microscopic urine findings. The appearance of five or more red blood cells in a clean midstream urine specimen, especially with at least a trace of albumin, suggests active nephritis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS, EXPECTED OUTCOMES, AND COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT

Self-Care and Complementary Therapies

Although it is impossible to prevent the onset of SLE, prevention of exacerbations may be possible. Avoidance of exacerbating factors may help reduce the number and severity of flare-ups.

These include sun exposure, injuries, insufficient rest, emotional crises, and medication cessation. Abruptly stopping medications, particularly large doses of corticosteroids, may even be fatal. Patients must be counseled about these factors. Several authors have implicated stress as a factor that can induce or exacerbate SLE. Different techniques such as biofeedback, visual imagery, stress reduction maneuvers, and acupuncture could be considered.

These include sun exposure, injuries, insufficient rest, emotional crises, and medication cessation. Abruptly stopping medications, particularly large doses of corticosteroids, may even be fatal. Patients must be counseled about these factors. Several authors have implicated stress as a factor that can induce or exacerbate SLE. Different techniques such as biofeedback, visual imagery, stress reduction maneuvers, and acupuncture could be considered.

General therapeutic considerations must always include rest and exercise. Rest is important in the treatment of fatigue secondary to SLE. It is essential during the early stages of the disease. These rest periods can be abolished when the patient feels better. Exercises that strengthen muscles and improve endurance while avoiding undue stress on the affected joints are recommended. Aquatic therapy is ideal.

The impact of the disease on the family needs to be discussed. Patients are often young adults who have children and other family members at home. Frequent office visits, hospitalizations, and even transplants will obviously affect each member of the family. Provisions for care of the other family members must be addressed. Other issues include women who want their own biologic children but are unable to maintain a pregnancy because of recurrent spontaneous abortions or the side effects of the medications.

Patients need to understand their disease and participate in their care. In addition to avoiding the exacerbating factors (see above), they must be reminded that SLE is multisystemic. All health providers, including dentists, should be told about their disease. All patients with SLE should receive antimicrobial prophylaxis before and during surgery, including dental procedures (Klippel, 1997). Patients may learn more about SLE from the Arthritis Foundation (see the list of resources at the end of this chapter).

Before initiating treatment, the following questions should be answered:

Does the patient fulfill the ACR criteria for SLE (see Table 40-1)?

If the patient has lupus, is life-threatening organ involvement present, or does the patient have mild disease?

Does a particular aspect of the patient’s disease require specific treatment (eg, seizures, Raynaud’s phenomenon, or cognitive dysfunction)?

Medication Regimen

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are mainstays in the therapy of non-organ-threatening lupus. Eighty percent of lupus patients are given NSAIDs. The NSAIDs are useful in treating fever, arthralgia, headaches, pleuritis, and pericarditis. However, complications of NSAID use are more common in SLE patients than in patients with nonrheumatic diseases.

Antimalarial drugs such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are effective nonsteroidal drugs for some patients with non-organ-threatening lupus. These drugs are most effective for the treatment of cutaneous lesions, arthritis and arthralgia, fatigue, and serositis. Chloroquine tends to be more effective than hydroxychloroquine. Atabrine is most effective for cutaneous lesions and fatigue. The chloroquines and atabrine are effective in 1 to 2 months and may be used synergistically. Generalized gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal complaints may occur, but they are reversible and often minor. The chloroquines can cause retinal damage; however, retinal damage has not been reported in patients taking recommended doses who undergo ophthalmologic exams every 6 months.

Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive medications. They are used in the active lupus patient who has heart, kidney, hematologic, or central nervous system involvement. They are also used in small doses in patients with fever, arthritis, mild serositis, rash, and fatigue whose disease did not respond to NSAIDs or antimalarial drugs. Daily oral dosing is used in most patients with active disease. With severe disease, such as severe nephritis, high-dose intravenous pulse therapy may be warranted. The most commonly used corticosteroid preparations are prednisone and methylprednisolone. However, side effects such as hyperglycemia, hypertension, edema, premature cataracts, osteoporosis, depression and psychosis, gastric irritation, and predisposition to infections limit their use.

The use of cytotoxic or immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclophosphamide and azathioprine is limited by their common and potentially life-threatening side effects. They are used only in patients with organ-threatening disease or patients whose disease fails to respond to corticosteroid treatment, or when the benefits of a steroid-sparing agent outweigh the risks of administering these medications.

Controlled trials have demonstrated the superiority of using cytotoxic drugs plus corticosteroids over the use of corticosteroids alone. These studies include well-designed controlled trials in lupus nephritis and chronic active “lupoid” hepatitis.

REFERRAL POINTS AND CLINICAL WARNINGS

Early warnings that may indicate a flare-up of SLE include chills, fatigue, fever, or any of the symptoms listed in Table 40-1. The provider should be notified if any new symptom occurs. If a patient is still having flare-ups while taking oral corticosteroid therapy, a consultation with a specialist is recommended. Because SLE is potentially fatal, whenever the diagnosis is questioned, treatment seems ineffective, or uncertainty about the prognosis or sequelae exists, a referral is warranted.

CLINICAL PEARLS

A positive test for ANA does not necessarily mean the patient has SLE. The frequency of ANA positivity increases with age. Twenty-five percent of persons over age 60 have a positive ANA test.

A negative test for ANA makes the diagnosis of SLE unlikely.

The symptoms of SLE may be vague. At times, constitutional symptoms, arthralgia, and a rash may be the only manifestations. Whenever more than one organ system is involved, think connective tissue disorder.

SLE may be fatal. When in doubt about any aspect of the disease, diagnosis, or treatment, request a consultation.

SLE is multisystemic. Remember to examine all organs (on physical exam and with laboratory testing) for possible involvement.

Sjögren’s Syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome (sicca syndrome) is a slowly progressive inflammatory autoimmune disease affecting primarily the salivary and lacrimal glands. In the absence of other autoimmune diseases, the syndrome is classified as primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

Secondary Sjögren’s syndrome accompanies other connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and systemic sclerosis.

Secondary Sjögren’s syndrome accompanies other connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and systemic sclerosis.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

The histopathologic hallmark of Sjögren’s syndrome is focal lymphocytic infiltration of the salivary glands, lacrimal glands, or extraglandular organs without structural destruction. These foci range from small foci to diffuse lesions. The extent of inflammation in a biopsy specimen is established by a focus score; a focus is defined as an aggregate of 50 or more cells. At least 2 foci/4 mm2 of tissue are needed to be considered positive. The focus score is based on the number of mononuclear cell foci in at least four or five salivary gland lobules.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Sjögren’s syndrome occurs primarily in women during the fourth and fifth decades of life, with a female/male ratio of 9:1. The prevalence in the general population is not known. However, the disease affects approximately 30% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

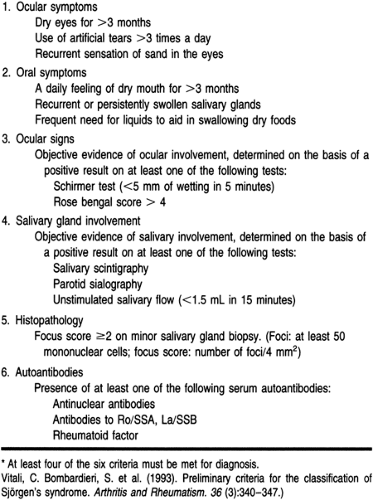

Table 40-2 lists the 1982 revised American College of Rheumatology criteria for diagnosing Sjögren’s syndrome (Vitali et al, 1993). They are based on physical findings as well as laboratory findings, including histopathology. A definite diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome can be made when four of the six criteria are met. Exclusion criteria include pre-existing lymphoma, AIDS, sarcoidosis, and graft-versus-host disease.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

History and Physical Exam

It is important to obtain a history of oral and ocular complaints. The patient should be asked about abnormalities of taste or smell, adherence of food to the buccal mucous membranes, difficulty chewing or swallowing, difficulty wearing dentures, and frequent ingestion of fluids. Ocular symptoms include a burning sensation, decreased tearing, a sensation of sand in the eyes, redness, and photosensitivity. The provider should also inquire about any parotid enlargement.

On physical examination, there is dryness of the buccal mucous membranes and lips and fissuring of the tongue. The normal pool of saliva under the tongue, visible when the tongue is elevated, is not present. Lesions such as oral candidiasis may be noted; it occurs with increased frequency in these patients.

Gross inspection of the eyes may be unrevealing. The results of a Schirmer’s test, a crude measurement of tear formation, are abnormal. In this test, a strip of filter paper is placed in the lower palpebral fissure. After 5 minutes, the moistened portion normally measures 15 mm or more. Wetting less than 10 mm in 5 minutes indicates an abnormal test. Most patients with Sjögren’s syndrome moisten less than 5 mm of the test paper. A more reliable diagnostic test is epithelial staining with rose bengal. Normally, no stain is visible a few minutes after dye instillation. Grossly visible or microscopic staining of the conjunctiva or cornea indicates the presence of small, superficial erosions.

The provider should differentiate between primary and secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or systemic sclerosis in the context of sicca symptoms suggest a diagnosis of secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. Sicca syndrome without evidence of another connective tissue disease indicates primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

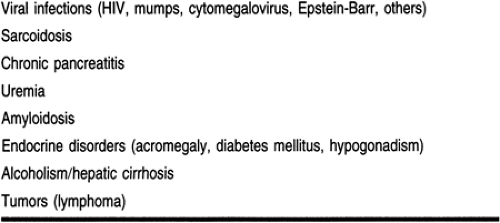

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome presents with a rapid development of severe oral and ocular dryness, often accompanied by episodic recurrent parotid gland swelling and pain in an otherwise well patient. Secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, on the other hand, develops insidiously. Approximately half of all Sjögren’s syndrome patients have parotid gland enlargement, often recurrent and asymmetrical. Sometimes it is accompanied by fever, tenderness, or erythema. Rapid fluctuations in gland size are not unusual. However, salivary gland enlargement is not pathognomonic of Sjögren’s syndrome (Table 40-3).

Salivary insufficiency can be very distressing to patients. Patients may require frequent ingestion of liquids, mainly at mealtime and at night. Many patients keep a water bottle by the bedside in case they are awakened by a dry mouth. Patients also experience difficulty chewing and swallowing dry foods such as crackers. Abnormalities of taste and smell may also occur.

Extraglandular involvement results in interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis. When the lower respiratory tract is involved, there is hoarseness, chronic cough, and increased incidence of

infection. Skin or vaginal dryness is common. Decreased vaginal secretions lead to vaginal and vulvar irritation and itching, decreased resistance to vaginal infections, and dyspareunia. Involvement of the gastrointestinal glands results in dysphagia and atrophic gastritis. Major renal complications include diabetes insipidus and renal tubular acidosis.

infection. Skin or vaginal dryness is common. Decreased vaginal secretions lead to vaginal and vulvar irritation and itching, decreased resistance to vaginal infections, and dyspareunia. Involvement of the gastrointestinal glands results in dysphagia and atrophic gastritis. Major renal complications include diabetes insipidus and renal tubular acidosis.

Disease Course

Although it is impossible to prevent the development of Sjögren’s syndrome, patients need to be educated about the complications of Sjögren’s and the increased risks of developing other diseases. (For more information on self-care resources, see the resource section at the end of this chapter.) Pregnant women who have Sjögren’s syndrome should be tested for antibodies to SS-A. The presence of anti-SS-A antibodies is associated with congenital heart block and rash in newborns. In addition, the estimated risk that a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome will develop malignant lymphoma is 43.8 times that of the general population (Kassan et al, 1978).

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

There are many laboratory aids for the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. A complete blood count often shows anemia of chronic disease. Leukopenia has been reported in a third of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Acute-phase reactants such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are elevated in most patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

Other laboratory studies may heighten suspicion of Sjögren’s syndrome, although none are specific. Elevated serum immunoglobulin levels are present in half of the patients. Antinuclear antibodies are present in approximately 65% of patients: antinuclear antibodies to SS-A and SS-B are found in 25% to 45% of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Positivity for rheumatoid factors is present in 90% of patients. Patients with Sjögren’s syndrome exhibit high levels of antibodies to mitochondria, thyroid gland, and smooth muscle, as well as many other autoantibodies.

Sjögren’s syndrome elicits a characteristic pattern on sialography, and radionucleotide scanning of the salivary gland demonstrates decreased function. A salivary gland biopsy demonstrates characteristic histology and confirms the diagnosis. Labial salivary gland biopsy is a safe, widely accepted method for ascertaining salivary gland inflammation. Major salivary gland biopsy is recommended only when there is a suspected malignancy or there are serious diagnostic doubts.

TREATMENT OPTIONS, EXPECTED OUTCOMES, AND COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT

Teaching and Self-Care

The management of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome should focus on improving sicca symptoms and treating associated disorders. It is important to avoid treating patients with Sjögren’s syndrome with medications such as antihistamines, cyclic antidepressants, or other anticholinergic drugs that inhibit glandular secretion. Alcohol and smoking should also be avoided. However, the most important aspect of therapeutic management is regular outpatient care by the primary care provider, ophthalmologist, and dentist.

Frequent dental visits are advisable. Regular and frequent brushing with a soft-bristled toothbrush and fluoride toothpaste and the use of dental floss, oral fluoride gels, and mouthwash are strongly advocated for dental caries prophylaxis. Sugarless gum or candies should be used to stimulate saliva production.

Several over-the-counter and prescription tear substitutes are available for treating keratoconjunctivitis sicca. For patients with sensitivity to the preservatives, preservative-free solutions are available. Repeated instillation of drops may be necessary to control symptoms. A high-viscosity tear substitute may provide more comfort but can cause blurred vision. Lacriserts, a solid form of artificial tears that dissolve slowly when the eye is closed, may be useful at night.

If corneal ulceration is present, patching the eyes and applying a boric acid ointment may be necessary. Topical corticosteroids are generally avoided because corneal thinning and subsequent perforation may occur.

Xerostomia is difficult to treat. Several saliva substitutes are available, but they provide only temporary relief. Increasing fluid intake is an effective way of eliminating the symptoms. Sugarless gum or candy may promote salivary flow through masticatory stimulation. Pilocarpine in 2% solution may increase salivary flow too, but adverse side effects such as flushing, transient sweating, and urinary urgency may occur.

Nasal dryness is best treated with a humidifier in both the patient’s house and office. Vaginal dryness may be treated by frequent applications of saline soaks, Replens, or even cooking oils. Lubricants are recommended for sexual activity. Skin dryness is managed with over-the-counter emollients and moisturizers. Postmenopausal estrogen replacement therapy may also be beneficial.

Medication Regimen

Treatment regimens are aimed at alleviating the symptoms of the disease, not at treating the disease itself. The management of rheumatoid arthritis or other associated disorders is not altered by the presence of Sjögren’s syndrome. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy may be useful for alleviating myalgias and arthralgia or arthritis. Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), 400 mg/day, has been associated with improvement in energy level and joint and muscle pain but no change in sicca symptoms (St. Clair, 1992).

Oral candidiasis can be managed by oral miconazole, 100,000 to 400,000 units five times per day, or nystatin, 400,000 to 500,000 units swished and swallowed four times a day. Systemic therapy (with oral fluconazole) is indicated in severe recurrent oral candidiasis.

Surgical Intervention

Patients who have limited residual tear flow unresponsive to tear substitutes may benefit from nasolacrimal punctal occlusion by electrocautery or argon laser. Patients whose symptoms fail to improve with punctal occlusion may be candidates for soft contact lenses, creating a reservoir for the tears and the protective film over the corneal surface.

REFERRAL POINTS

Sjögren’s syndrome is usually not a life-threatening illness but is extremely annoying and disabling. Symptoms are usually alleviated by the recommendations mentioned above. If, however, the patient is still symptomatic, advice from or referral to a rheumatologist or ophthalmologist is warranted. In addition, a referral to a rheumatologist may be needed to help control concomitant disease.

CLINICAL PEARLS

Making the patient comfortable is the mainstay of treatment.

Although symptoms are bothersome, patients are often reluctant to mention them to the provider, especially those related to vaginal dryness and sexual activity. The provider should inquire about symptoms in a nonjudgmental, compassionate fashion.

Many of the treatments are self-initiated and do not require prescriptions, but patients need to know their options and what is and is not safe to use.

Patients always seen sucking on hard candy or never parting from a water bottle should raise the suspicion of Sjögren’s syndrome.

Always look for associated connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

There is a small but real risk for B-cell lymphomas.

Diuretics and anticholinergic medications should be avoided secondary to decreased tears and saliva.

Systemic Sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis is a connective tissue disease characterized by thickening and fibrosis of the skin (scleroderma), Raynaud’s phenomenon, and widespread damage to the microvasculature. Musculoskeletal manifestations and distinctive internal organ involvement, notably of the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, heart, and kidneys, may be present.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

The pathologic features of scleroderma consist primarily of fibrosis, atrophy, inflammation, and a distinctive change in vasculature. These pathologic changes occur in all involved organs. The excessive accumulation of collagen in the dermis is the pathologic hallmark of systemic sclerosis and leads to the clinical manifestations of taut skin. The fibrosis may be patchy or diffuse, and atrophy appears to represent an end-stage process. However, the vascular lesions appear to be the primary determinant of prognosis. It is theorized (Smith & Leroy, 1994) that some unknown inciting event triggers endothelial cell injury and immune system activation. The injury results in release of platelet constituents capable of causing fibroblast proliferation and matrix synthesis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of systemic sclerosis is 4.5 to 12 new cases per million per year. The female/male ratio is approximately 3:1. The usual age at onset is between the third and fifth decade, with 80% of cases occurring between ages 20 and 60 (Medsger & Masi, 1971, 1978). No significant racial differences have been observed (Medsger & Masi, 1971, 1978). Patients with systemic sclerosis are more often employed as laborers or other less-skilled jobs and have larger ethanol intakes than control patients (Medsger & Masi, 1978). Occupational exposures that may be related to development of systemic sclerosis include polyvinyl chloride, coal and gold mining, and silica dust exposure.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The criteria used to make a definitive diagnosis of systemic sclerosis are listed in Table 40-5. The major criteria must be present, or two or more of the minor criteria. Once diagnosed, systemic sclerosis may be classified by clinical features, focusing primarily on skin thickness (Smith & Leroy, 1994). Table 40-4 describes the findings in each of the classes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree