INTRODUCTION

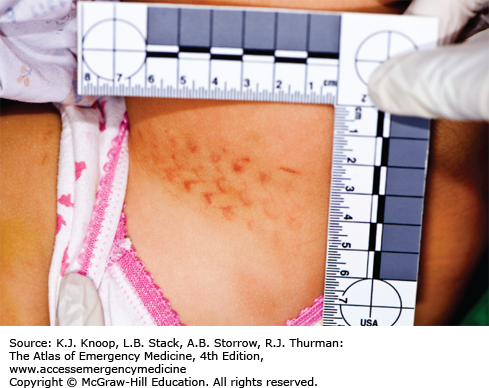

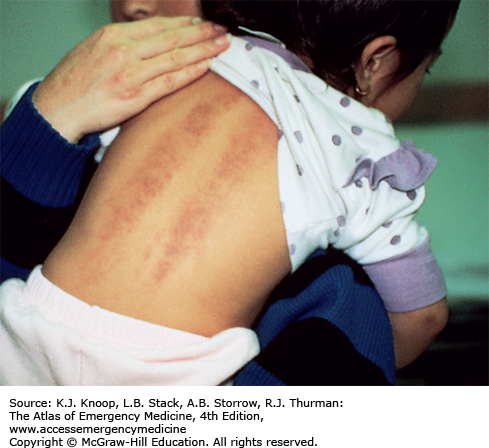

Physical Abuse: CUTANEOUS FINDINGS

Bruises are the most common manifestation of child physical abuse. Children younger than 6 months and those that are not yet “mobile” rarely have any bruising from accidental injury. In older children, bruising to the abdomen, ear, neck, cheek, buttocks, or genitals is also less likely to be the result of accidental injury. Child abuse should also be strongly considered when a bruise takes the shape of an object (belt, cord, hand).

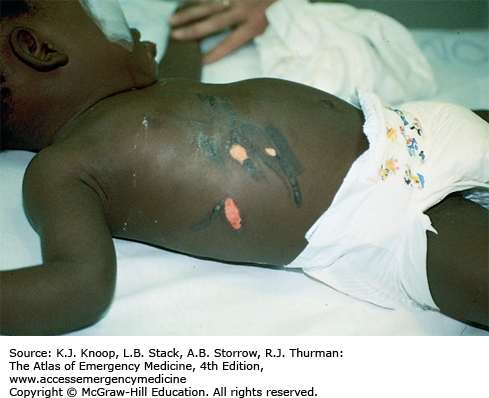

Certain clues may assist in differentiating abusive from accidental burns, but, often, doubt remains even after careful evaluation. With an immersion burn, the child is held into or under hot liquid and the burn margins are usually distinct. A “splash” pattern, conversely, will occur when a child attempts to get out of the way of the hot liquid; the burn margins are less distinct and there may be additional adjacent small burns. Contact burns usually have distinct and recognizable shapes but it is sometimes difficult to determine how the burn occurred. A child who has multiple contact burns or burns to areas that are unlikely to come in contact with the hot object accidentally should be evaluated for abuse.

While certain findings (bite marks, patterned bruises) are very specific for abuse, cutaneous findings are not sensitive for predicting other injuries such as fractures, brain injury, or abdominal injury. The absence of bruising should not preclude screening for other injuries.

With the exception of significant burns, abusive cutaneous injuries rarely require significant treatment. Rather, children with concerning cutaneous findings should be screened for other abusive injuries and medical mimics of abuse. Order neuroimaging (CT or MR) for children less than 6 months of age, skeletal survey for children less than 2 years old, and hepatic transaminases (alanine transferase [AST]/aspartate aminotransferase [ALT]) for children less than 5 years old. Order prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT) and complete blood count (CBC) for children with concerning bruises or other findings that could indicate a coagulopathy and consider hematology consultation for other coagulopathy testing.

If a human bite is suspected, photo document and swab for potential DNA analysis. Run a moistened swab followed by a new dry swab over the area and clearly follow and document chain of evidence. If available, consult with a forensic dentist.

Report suspected abuse to the legally mandated child protection agency before the child is discharged from the emergency department (ED). In the United States, medical professionals have a legal mandate to report in cases concerning for child abuse. When available, consult with the Child Abuse Team.

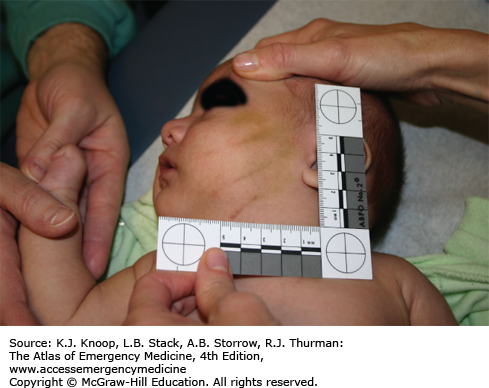

Use the distance between the maxillary canines to determine if the biter was someone with primary teeth (child) or secondary teeth (adult). Most adults have greater than 29 mm distance.

Do not use the color or appearance of a bruise to estimate its age. Despite a widely cited dating schema, there is no evidence to support this.

Cigarettes can burn as hot as 400 to 700°C. Inflicted cigarette burns are therefore usually ulcerated and full-thickness, rarely superficial.

Burn mimics to consider include impetigo, phytophotodermatitis, and contact dermatitis. Bruise mimics to consider include hemophilia, von Willebrand disease, Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP).

Place a millimeter ruler or a coin in the field when photographing injuries, and photograph at a 90 degree angle to the plane of the finding.

Genital bruising is always concerning for child abuse. Physical abuse as well as sexual abuse should be considered.

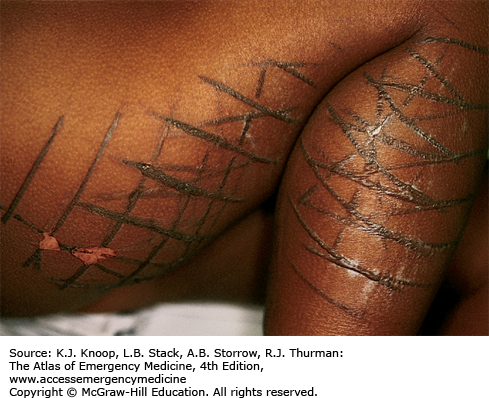

FIGURE 15.12

Folk Remedies: Coining. This child has linear petechiae along her spine from the Southeast Asian practice of coining (Cheut Sah or Cao Gio) where a coin is rubbed along the skin to heal illness. This practice is neither painful nor dangerous and is not abusive. Another folk remedy, cupping or moxibustion (not shown), produces circular bruising when a match is used to create a vacuum inside a glass placed on the skin. (Photo contributor: Charles Schubert, MD.)

FIGURE 15.13

Folk Remedies: Cupping. Circular “burns” from the practice of “cupping” result when warm cups are placed on the skin to draw out illness. (Reproduced with permission from American Academy of Pediatrics. Visual Diagnosis of Child Abuse. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1994.)

FIGURE 15.14

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP). This child has palpable purpura on the extensor surfaces of the legs. HSP should be considered whenever there is symmetric ecchymosis along the extensor surfaces of the extremities and buttocks. Migratory arthritis and abdominal pain may be present. (Photo contributor: Ralph A. Gruppo, MD.)

FIGURE 15.15

Dermal Melanosis (Mongolian Spots). These blue-gray congenital marks are more common in darker-skinned children. Frequently found on the buttocks or low back, they can be seen anywhere. They are distinguished from bruising because they fail to resolve in days or weeks. (Photo contributor: Kathi L. Makoroff, MD.)

FIGURE 15.18

Immersion Burn. Immersion burns are often associated with toilet-training accidents. This girl was plunged into hot water after soiling herself. She shows sparing of the buttocks, which contacted the surface of the bathtub and avoided being burned. (Reproduced with permission from American Academy of Pediatrics. Visual Diagnosis of Child Abuse. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1994.)

FIGURE 15.20

Splash Burn. This toddler pulled a cup of hot liquid on to her. Note the “flowing” pattern that starts on her face and extends down her arm with burn depth decreasing as the liquid flows and cools. Also characteristic are “skip” areas of skin that are not affected. (Photo contributor: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.)

FIGURE 15.22

Scald Burn with Sparing. Superficial and partial-thickness burns were noted on the patient’s anterior surface only. The areas of abdominal sparing indicate that the victim was flexed and curled at the time of injury. The child’s caretaker, the mother’s boyfriend, admitted to holding the child under a running hot-water tap. Partial-thickness burns on the penis and medial thighs are indicative of pooling of the liquid in those areas, resulting in a time-dependent injury. (Photo contributor: William S. Smock, MD.)

FIGURE 15.23

Cigarette Burn—Inflicted. Cigarette burns are circular injuries with a diameter of about 8 mm. Children who accidentally run into a lit cigarette often have burns to the face or distal extremities. Accidental burns may be less distinct or deep compared with inflicted burns. (Photo contributor: Kathi L. Makoroff, MD.)

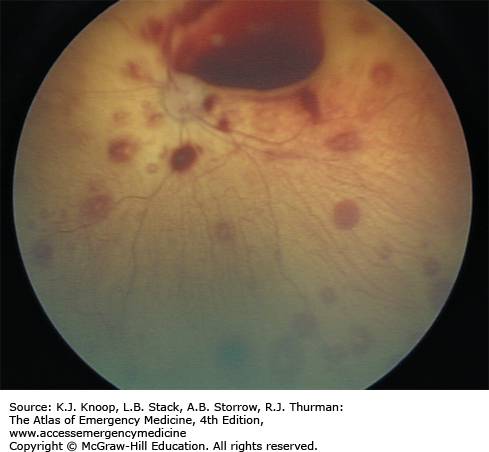

CRANIAL FINDINGS

Abusive head trauma (AHT) (formerly shaken baby syndrome) is an important cause of morbidity and mortality from child physical abuse. Subdural hematoma is the most common finding. Skull fractures and/or cerebral edema can also be present. Retinal hemorrhages do not have to be present to make the diagnosis of AHT. Retinal hemorrhages that are numerous, multilayered, and extend to the periphery have only been described in infants and children with significant trauma including AHT. Fewer hemorrhages clustered around the posterior pole of the retina have been described with less severe trauma and in critically ill children with no concern for abuse and are, therefore, less specific. Retinal examinations without dilation, or by nonspecialists, are limited. All children with traumatic brain injury and concern for abuse should be examined by an ophthalmologist with pediatric experience.

Infants and children with head injury should be treated as medically appropriate. Subdural hemorrhages can be seen in infants and children with nonspecific (fussy, vomiting, less active) or no symptoms. Therefore, have a low threshold for ordering neuroimaging in an infant or child who has other concerning signs of abuse (bruising, fractures).

In the absence of major trauma, subdural hematomas are very concerning for abuse, and should trigger a thorough search for other abusive injuries, coagulopathy, or a history of abuse. A report of suspected child abuse should be made to children’s services if there is a concern for AHT.

A history that a short fall or other minor injury caused a significant intracranial injury should be highly suspected.

Infants and children with AHT may have no external signs of trauma and nonspecific or no neurologic deficits.

Minor skull fractures can occur accidentally and are impossible to date.

CT can identify significant soft tissue injury that is missed on physical examination.

Significant retinal hemorrhages are exceedingly rare if neuroimaging is negative. Dedicated retinal exam may be omitted if traumatic brain injury is absent.

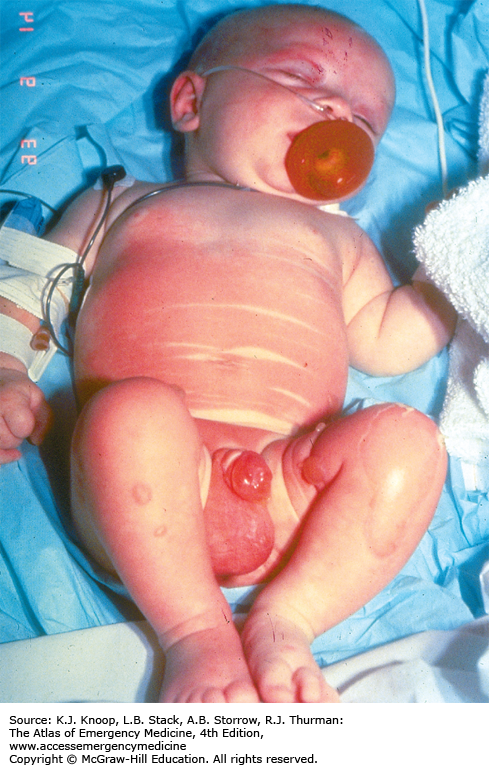

FIGURE 15.28

Subdural Hematoma and Extra-Axial Swelling. This image shows intrahemispheric acute subdural blood (large arrows) and subtle contusions (black arrows) of the frontal lobes. Extracranial soft tissue swelling (arrow heads) is also present; sometimes this is visible on CT but not on physical examination. (Photo contributor: Marguerite Care, MD.)

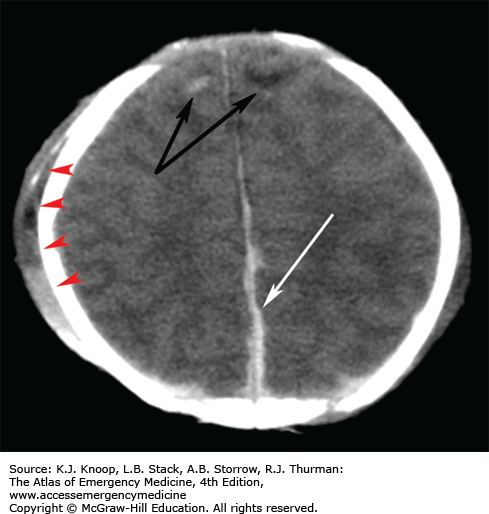

FIGURE 15.30

Vertex Skull Fracture. This infant was accidentally dropped on her head. The 3D reconstructed image shows two fractures that originated from the anterior fontanelle. It is possible that two distinct fractures resulted from a single impact to the vertex of the head. (Photo contributor: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.)

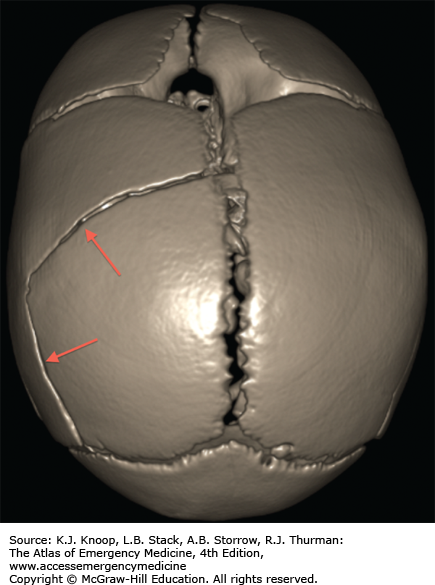

FIGURE 15.31

Retinal Hemorrhages. Multiple retinal hemorrhages (too numerous to count) are present in this image. A pediatric or general ophthalmologist can obtain a more complete view of the retina with dilated direct ophthalmoscopy and should be consulted to evaluate for retinal hemorrhages. (Photo contributor: Rees W. Sheppard, MD.)

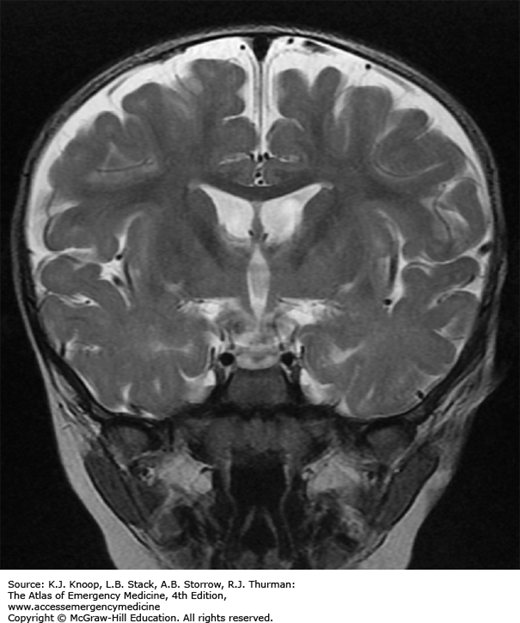

FIGURE 15.33

Benign Extra-Axial Fluid. This coronal T2-weighted MRI shows enlarged subarachnoid spaces (vessels running through). This can be a common finding in children with macrocraina. The enlarged spaces can be confused for subdural collections which will then raise the concern of abusive head injury. (Photo contributor: Marguerite Care, MD.)

FACIAL FINDINGS

Because crying and feeding difficulties can serve as the trigger for physical abuse, the face is frequently the site of the most forensically significant, even if subtle, signs of abuse. Carefully examine the oral cavity, ears, and fontanel of all children with concern for abuse. Force-feeding or forceful insertion of utensils or fingers into a child’s mouth can result in injury to lips, frenula, or palate, as well as deeper oropharyngeal injury. Accidental oropharyngeal injuries are commonly caused in older children by toothbrushes, lollipops, or popsicle sticks, but these findings are concerning for abuse in children who are not yet ambulatory.

Most abusive facial injuries are minor or self-limited, and are most important as an indication for further screening for other occult injuries, especially AHT. Bruising to the ear is very concerning for abuse, as are injuries to the labial or lingular frenula, or palate in children who are not yet walking. All injuries concerning for abuse should be photographed and carefully documented in the medical record.

Children with abusive oropharyngeal injuries should be evaluated as other children with accidental oropharyngeal injuries, with low threshold to image (MRA or CTA) to identify vascular injury or deep space infection or abscess.

FIGURE 15.37