Breast Mass

Seth P. Harlow MD

Hyman B. Muss MD

Diseases of the breast are common clinical problems that are frequently seen in primary care practice. The most important aspect of managing breast problems is the early recognition of breast cancer. With the exception of skin malignancies, breast cancer is the most common malignancy affecting women in the United States today. Recently, a great deal of public attention has been focused on improving methods of early detection and developing new treatments for patients with breast cancer. Together with the patient, the primary care provider is the crucial first link in the effort toward prevention and early detection of breast cancer. Primary care providers must become adept at risk assessment and early diagnosis of these lesions. Breast cancer survival is clearly related to detection at an earlier stage of disease, which can best be insured by providing patient education and following screening guidelines. All women should be considered to be at risk for breast cancer and should undergo recommended screening. Use of screening guidelines has led in large part to a recent decrease in the annual mortality rate from breast cancer. Developing a systematic approach to the screening and evaluation of new breast problems is essential to provide the best possible patient care in this age of cost containment.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

Until puberty, the female breast is a rudimentary structure consisting of only a few ducts without acini. Under the influence of estrogens, progesterone, and the pituitary hormones, ductal tissue begins to grow, bud, and form acini at puberty. Glandular tissue separates into 12 to 20 lobes, or segments, extending from the nipple in a radial fashion. The ducts from each segment empty into a single lactiferous sinus that terminates at the nipple. The glandular tissues of the breast undergo cyclical changes in response to the hormone fluctuations during the menstrual cycle. At the start of the cycle, the ductal cells proliferate, there is an increase in interstitial fluid, and a lymphocytic infiltration is seen. This reaches a maximum just before the menses, at which time the ducts shrink and the ductal epithelium is shed. The cycle then repeats itself. These changes may lead to subsequent dilatation or hyperplasia of the ducts, hypertrophy of the surrounding connective tissue, and many benign pathologic conditions loosely referred to as fibrocystic changes.

During pregnancy, the breast lobules undergo maximal proliferation, and alveoli form. This proliferation is stimulated by the placental hormones. After delivery, the withdrawal of the placental hormones, along with prolactin secretion by the pituitary gland, stimulates lactation. Milk is produced by shedding of the alveolar cells. After the completion of lactation, the breast glandular tissue partially involutes. At menopause, there is further involution of the glandular tissue of the breast, with loss of the lobular outlines. Fibroglandular tissue is replaced by fatty tissue.

Common abnormalities of breast development include accessory nipples and ectopic glandular tissue. These abnormalities may occur anywhere along the “milk line,” which extends from the axillae, through the nipple and down to the inguinal ligament. Accessory breast tissue (polymastia) is most often seen in the axilla; accessory nipples (polythelia) are most often seen in the midclavicular line below the normal breast.

The lymphatic drainage of the breast is predominantly toward the ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes. Lymphatic drainage in the medial aspect of the breast may also proceed toward the internal mammary nodes or the interpectoral nodes. Lymphatic spread of breast carcinoma cells may lead to enlargement of the axillary lymph nodes, which may be apparent on physical examination.

Breast lesions may be classified into five broad histopathologic categories:

Benign, nonproliferative lesions carry no increased risk of subsequent development of malignancy. Benign lesions include:

Cystic hyperplasia (fibrocystic disease)

Duct ectasia

Galactoceles

Lipomas

Fat necrosis

Fibroadenoma

Hamartoma

Papilloma

Inflammatory lesions

Benign proliferative lesions include:

Ductal hyperplasia without atypia, which carries no significant increased risk for subsequent malignancy (Dupont & Page, 1985)

Atypical ductal hyperplasia, which carries an increased risk of subsequent malignancy (Dupont & Page, 1985)

Atypical lobular hyperplasia, which also carries an increased risk of subsequent malignancy (Dupont & Page, 1985)

Sclerosing adenosis, which has no significant link to subsequent malignancy (Jensen et al, 1989)

In situ carcinomas are malignant-appearing cells that lack evidence of invasion through the basement membrane. These include:

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), considered a marker for increased risk of subsequent cancer development in either breast (Carson et al, 1994)

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), considered a direct precursor to invasive ductal carcinomas

Invasive carcinomas are malignant cells that demonstrate invasion of the basement membrane. These lesions have the potential for metastatic spread.

Invasive ductal carcinoma (80% of invasive carcinomas)

Invasive lobular carcinoma (15%)

Medullary carcinoma, tubular carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, and papillary carcinoma (5%)

Other malignancies include:

Phylloides tumors (20% to 30% have malignant features)

Soft-tissue sarcomas

Lymphomas

Metastatic Tumors.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of breast cancer steadily increases with age. Breast cancer is rare in patients under 20 years of age, but its incidence begins to rise rapidly during the childbearing years. The rate of breast cancer continues to increase after menopause but at a slower rate. Women in the United States currently have a lifetime risk of developing breast cancer of approximately 12% and a lifetime risk of dying of breast cancer of approximately 3.6% (Hankey et al, 1993).

The incidence of breast cancer in men is approximately 0.5% to 1% the rate of breast cancer in women. There are about 1000 new cases of these cancers per year in the United States. Male breast cancers typically present as palpable masses, with a pattern of spread and prognosis similar to those in women (Boring et al, 1994).

The incidence of breast cancer is higher in the United States and western Europe than in other parts of the world. In the United States, the rates are highest in whites and persons of Hawaiian descent. These rates decrease in women of African American, Asian American, and Hispanic American heritage. Native Americans have a particularly low rate of breast cancer (Muir et al, 1987).

CLINICAL WARNING

Women of African American background have a mortality rate about 10% higher than white women, even when matched for stage.

The incidence of breast cancer shows a steady increase from lower to middle to upper socioeconomic groups. The reason for this increase is not entirely clear, but it may be related to reproductive, dietary, or environmental factors (Krieger, 1990).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Diagnostic criteria are defined by the pathologic findings.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

The primary care provider must document the following:

Age (ie, postmenopausal)

Age of menarche and, if applicable, menopause

Age of first full-term pregnancy

Use of hormones

Family history of breast and other cancers

Prior breast biopsies.

The provider should screen for the following symptoms:

Palpable lesion

Skin or nipple changes

Nipple discharge

Breast pain.

The clinical breast exam should focus on:

Inspection

Skin dimpling

Skin redness

Nipple retraction

Nipple excoriation

Visible masses

Palpation

Palpable masses

Asymmetric thickening

Nipple discharge

Axillary lymph nodes.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Screening mammography is a routine component of health maintenance. Current recommendations for screening are discussed later in this chapter. Screening mammograms should include:

Standard two views of each breast

Additional views if abnormalities are seen.

Mammographic Abnormalities

Correct identification of any abnormalities will support effective, timely management.

Macrocalcifications are calcifications that measure more than 1 mm. They are usually benign. Microcalcifications measure less than 1 mm. It is suspicious for malignancy if there are more than five microcalcifications per cubic centimeter, if they are pleomorphic in appearance, or if they are increased in number from prior mammograms.

Lesions are classified as benign if:

Calcifications show as meniscus on lateral views, are spherical or eggshell in appearance, or are large and rod-shaped.

Mass lesions which are smooth-walled and well defined are usually benign but need further evaluation by ultrasound.

A border that is irregular or speculated is suspicious for malignancy. An asymmetric density may represent malignancy.

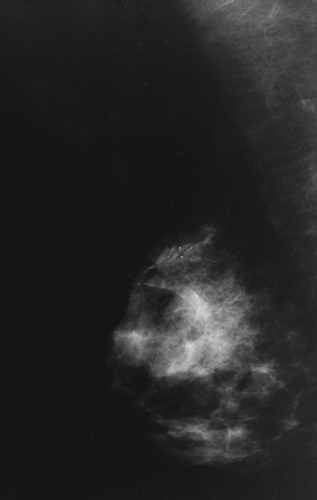

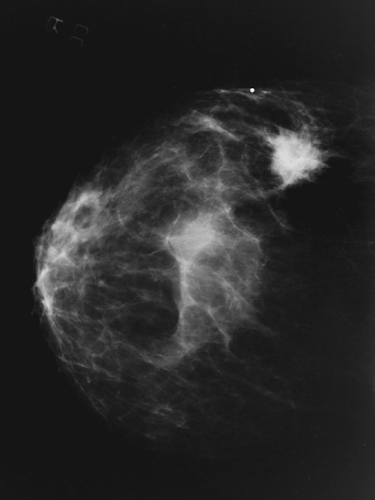

Figures 65-1 and 65-2 illustrate views of two breast malignancies visible on mammography.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is a valuable adjunct to the physical exam and mammography. Its benefits include the following:

It provides better resolution of mass lesions in dense breast tissue, or breasts that have been previously irradiated.

It can distinguish solid from cystic lesions.

It is portable and easily accessible.

It does not expose the patient to radiation.

It allows image-guided biopsies.

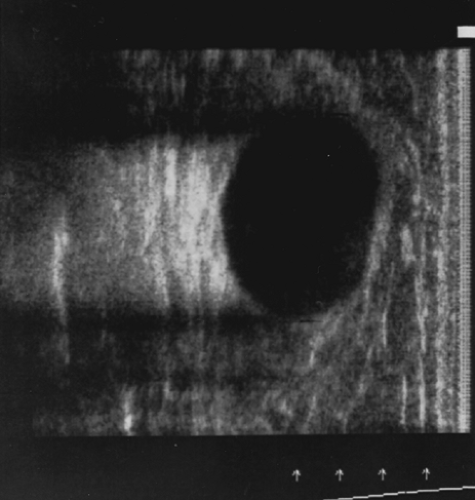

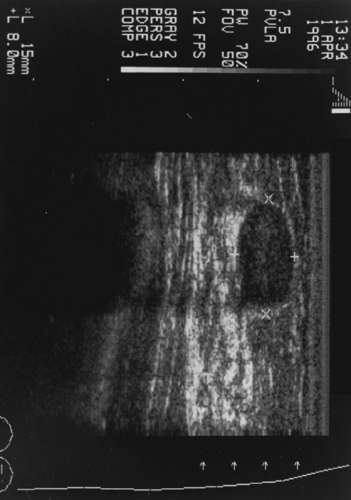

However, ultrasound will not identify calcifications or small masses in breasts with fat replacement. Figures 65-3, 65-4, and 65-5 illustrate views of three breast lesions visible with ultrasound.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Several drawbacks make the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) less than practical in most clinical screening situations. Significant among these drawbacks is its expense. MRI also has a relatively low specificity for breast cancer (30% to 40%) (Heywang-Kobrunner, 1994). Finally, MRI is not widely available outside of more metropolitan areas.

CLINICAL PEARL

MRI is useful in two situations: its high sensitivity for breast lesions (88% to 100%) and its value in detecting leaks from breast implants.

Biopsy Techniques

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is carried out using a 25- to 27-gauge needle. Little specialized equipment is needed. FNA is less traumatic than other biopsy techniques. Aspirated material must be interpreted by a cytopathologist skilled in this area.

Core needle biopsy is carried out using a 14- to 18-gauge needle; a specialized core biopsy needle is needed. A larger sample is required for standard histopathologic evaluation. This technique is more invasive than FNA.

Open surgical biopsy is the most invasive of the biopsy methods and is also the most costly. Potentially therapeutic, open surgical biopsy also produces fewer false-negative results.

TREATMENT OPTIONS, EXPECTED OUTCOMES, AND COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT

The causes of breast cancer are not understood and are likely to be multifactorial. Several factors are known to increase a woman’s risk for breast cancer:

A family history of breast cancer, particularly if one or more first-degree relatives are affected. Specific genetic abnormalities, including mutations of the BRCA1 and BRCA2, genes have recently been described (discussed below). If present, such genetic abnormalities have been found to confer a high risk (50% to 90%) that the patient will develop breast cancer. Other genetic syndromes predisposing patients to breast cancer include Li-Fraumeni (p53 gene mutation), Cowden’s, and ataxia–telangiectasia.

Early onset of menarche: Higher breast cancer risks are seen in patients with onset of menses before age 12 than in those with menarche after age 15 (Brinton et al, 1988).

Late onset of menopause: Higher breast cancer risks are seen in patients with natural menopause after age 55 than in those with menopause before age 45 (Trichopoulos et al, 1972).

Late age at first pregnancy: Women who have their first pregnancy after age 30 have been seen to have a small but significantly increased risk of developing breast cancer (MacMahon et al, 1970).

Postmenopausal obesity

Previous history of radiation to the chest

Higher socioeconomic status

Previous history of ovarian or endometrial cancer.

Many of the known risk factors for breast cancer can be altered, including diet and lifestyle habits. Altering these may lead to a slight reduction in breast cancer risk. For example, eating a diet that includes foods such as soybeans, which have large quantities of the phytoestrogens genistein and daidzein, may block the proliferative effects of endogenous estrogens. This in turn decreases the risk of breast cancer development (Barnes et al, 1994; Ingram et al, 1997).

Factors that may increase the risk for breast cancer include increased alcohol consumption (Longnecker et al, 1988) and a sedentary lifestyle (Bernstein et al, 1994). Several studies have suggested that women who follow a moderate exercise program may have a decreased risk for breast cancer, probably as a result of a decrease in their overall total body fat content (Bernstein et al, 1994; McTiernan et al, 1997). However, to date there is no convincing relation between dietary fat intake and breast cancer risk.

Chemopreventive Agents

Because of the hormonal influences associated with the development of breast cancer, much effort has been expended in designing chemopreventive agents that result in hormonal manipulation. The drug that has shown the greatest promise is the antiestrogen tamoxifen, which is used in the treatment of breast cancer. There are several large multicenter trials underway, including the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project prevention trial, to determine the efficacy of tamoxifen in reducing the incidence of breast cancer. (A recent preliminary report by the NSABP has shown a 45% reduction in breast cancer incidence in short-term followup of high-risk patients treated with tamoxifen vs. placebo [Wickerham et al, 1998]).

Other agents are also being investigated as potential chemopreventive agents, including retinoids and newly discovered phytochemicals. Again, it is likely to be several years before significant information is available as to the efficacy of these compounds.

Screening

Breast cancer screening has been the subject of much recent controversy. Like all other screening efforts, screening for breast cancer is used to identify disease at an earlier stage, before it becomes symptomatic. Early staging is important because it improves the patient’s chances for survival.

The first large study to suggest any improvement is breast cancer survival with screening was the Health Insurance Plan (HIP) of New York study (Shapiro et al, 1988). The HIP study showed an improvement in survival in women undergoing twoview mammography and physical exam every 12 months during a 4-year period compared with women not screened. Additional studies from Sweden have confirmed this improvement in breast cancer survival associated with the systematic use of screening mammography (Nystrom et al, 1993).

CLINICAL PEARL

The most significant improvement in survival in all studies to date has been in women older than 50. Annual mammography may decrease the risk of dying of breast cancer by as much as 30% in this age group.

The value of routine mammography in patients age 40 to 50 has not been completely resolved. Several randomized studies have produced conflicting results, leading to different recommendations for screening in this population. Current recommendations from the American College of Radiology, the American Cancer Society (Mettlin & Smart, 1994), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists suggest performing mammography every 1 to 2 years in women ages 40 to 49 and yearly after age 50, along with yearly clinical breast exams beginning at age 40. The recommendations from the National Cancer Institute and the American Board of Family Practice for women aged 40 to 49 with average risk is that the benefit of screening mammography is uncertain and should be discussed with each patient before proceeding (Fletcher et al, 1993).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree