Blunt Neck Trauma

Edward Ullman

The majority of blunt neck trauma occurs in conjunction with significant injuries to the head, cervical spine, and face (1). The most commonly reported injury is the “padded dash syndrome.” This occurs when the unrestrained driver decelerates against the steering wheel or dashboard. There have been case reports of isolated neck trauma due to a “clothesline” mechanism in motorcycle, jet ski, snowmobile, and all-terrain vehicle users (2,3). Strangulation occurs from hanging, ligature suffocation, and manual manipulation. Other etiologies include blunt impact secondary to a punch, kick, strike by a baseball bat or other object.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

There is a wide range of presentations in patients with blunt neck trauma; patients may be asymptomatic, have minimal symptoms, or present in extremis. Therefore, it is critical to recognize that a lack of obvious soft tissue trauma does not rule out a significant injury (2).

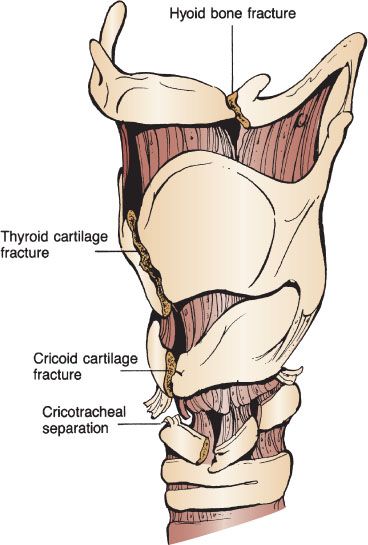

Airway injuries can present with hoarseness, stridor, subcutaneous emphysema, hemoptysis, or respiratory distress (4). Laryngotracheal injuries include vocal cord damage or disruption, dislocation of the arytenoid cartilage, tracheal transection, and fractures of the thyroid or cricoid cartilage or hyoid bone (Fig. 26.1) (5). Patients with any alteration in voice should be assumed to have a laryngeal injury. Development of a soft tissue hematoma or edema can externally compress the airway and cause respiratory compromise. Therefore, continuous airway reassessment is required in patients with blunt neck trauma. Palpation of the thyroid and cricoid cartilages will often reveal tenderness and crepitus as an indication of injury, especially in men, as these landmarks are prominent. If there is loss of definition or deviation of these structures, the likelihood of underlying injury is high.

FIGURE 26.1 Types of laryngeal injuries: hyoid bone fracture, thyroid cartilage fracture, cricoid cartilage fracture, cricotracheal separation.

The incidence of vascular injury in blunt trauma patients is 0.08% to 1% (6). As a result, blunt vascular injuries to the carotid or vertebral arteries are often diagnosed after admission (7). The majority of these injuries occur at the carotid bifurcation or higher and involve multiple vessels (8). Carotid injuries include intimal tears, hematoma, thrombosis, and pseudoaneurysms. Injuries that cause hyperextension and rotation can stretch the carotid artery and compromise the vessel. Acute flexion injuries may crush the carotid artery between the mandible and the cervical spine, leading to thrombosis or intimal damage. An intraoral blow to the soft palate can cause carotid thrombosis, especially in the pediatric population. This usually occurs when a child has an object in his or her mouth and falls, forcing the object into the soft palate. Carotid injuries can present with isolated ipsilateral cerebral findings that include contralateral hemiplegia, sensory loss, and aphasia (9). The presence of a bruit can indicate partial disruption of the carotid by either intimal dissection or thrombus formation. Patients may also present with Horner syndrome (ipsilateral miosis, ptosis, and anhidrosis) owing to disruption of the thoracic sympathetic chain that encircles the carotid artery.

The incidence of vertebral artery injury has increased (10). However, vertebral artery involvement remains difficult to diagnose. Many patients remain asymptomatic owing to an extensive collateral circulation (11). Those who have some deficit complain of vague symptoms such as dizziness, visual disturbances, nausea, and vertigo. Furthermore, because the vertebral artery connects to the basilar artery, an embolic event from trauma could affect either the ipsilateral or contralateral posterior circulation. This can leave the patient with a variety of neurologic deficits without an apparent vascular source.

Several studies recommend evaluation for vascular pathology if any of the following injuries are noted upon trauma evaluation: Horner syndrome; cervical spine fracture that involves the transverse foramen or a facet joint dislocation; Le Fort 2 or 3 fracture; and neurologic deficit not explained by a cervical spine fracture or abnormal head computed tomograph (CT) (12).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The existence of other associated injuries and the lack of external neck findings make vascular injuries difficult to diagnose. Neurologic deficits are often delayed; only 10% of those with vascular injury have initial findings. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with neurologic deficits not explained by head CT and in hemiparetic patients without alteration in mental status. In a series of 66 patients, 34% of those with neck vascular injuries had incongruent neurologic findings (6). The emergency physician should consider this diagnosis in patients with basilar skull fractures and marked external cervical trauma, as associated vascular injuries are often present. The diagnosis should also be considered in patients with anterior neck soft tissue injury such as abrasions, edema, or hematoma.

There are only 10 reported cases of isolated gastrointestinal injury in blunt neck trauma (13). The majority of these injuries occur in conjunction with laryngotracheal injury. Gastrointestinal injury should be considered in patients with pain on swallowing or subcutaneous emphysema; the latter group has a higher incidence of airway compromise.

ED EVALUATION

Because of the difficulty in diagnosing vascular, airway, and gastrointestinal injuries in blunt neck trauma, a systematic evaluation is critical. Table 26.1 lists signs that should raise the suspicion of a vascular injury. In the patient without signs of vascular injury the Denver Modification of Screening Criteria should be used to identify patients at high risk for injury who likely need imaging (14) (Table 26.2). These criteria have been used by the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (15).

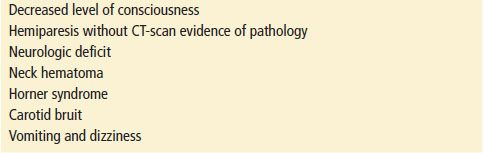

TABLE 26.1

Signs and Symptoms of Vascular Injury