INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

An adequate response to a bioterrorist event of any magnitude requires early recognition and effective coordination of many disparate health and medical entities beyond the ED. Although the emergency physician plays a critical role in these types of events, many other essential functions must be addressed by individuals and organizations representing public health, mental health, law enforcement, emergency management, and others.

A bioterrorist incident is the release, or the threat of a release, of a biologic agent among a civilian population for the purpose of creating fear, illness, and death. Such an occurrence is a low-probability, high-impact incident. For example, in the U.S. anthrax dissemination incident, the U.S. Postal Service was used to deliver letters containing spores of Bacillus anthracis. Although the environmental contamination was widespread, only 22 diagnosed cases of anthrax infection occurred: 11 cases of inhalational and 11 cases of cutaneous anthrax. Five patients died as a direct result of the anthrax exposure.1 Communities on the Eastern Seaboard of the United States were severely affected, with thousands of people receiving prophylaxis for anthrax.2 Fear then spread across the nation, as concern increased for a wider delivery of anthrax. Much of this national anxiety may have been exacerbated by the perception of an inadequate public health response capability, with the deficiencies demonstrating a critical need to integrate acute care medicine and the public health response.

Biologic agents are classified into two groups: biologically produced toxins and infectious organisms. Biologic toxins usually act as chemical agents in their human impact. The recognition and response requirements for these are very similar to those for chemical incidents. Infectious agents are subdivided into two categories: contagious (propagating person to person) and noncontagious. Contagious agents have additional ramifications, both for protection of the healthcare workforce as well as propagation of the disease beyond the initially exposed population. The contagious agents of greatest concern, such as smallpox, plague (pneumonic), and certain viral hemorrhagic fevers, are person-to-person infectious through airborne or droplet transmission. Suspected biologic agents causing illness should be treated as contagious until demonstrated otherwise.

AGENTS OF CONCERN

Certain characteristics make individual organisms particularly attractive as weapons for generating widespread fear, illness, and death among civilian populations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified select organisms and the diseases they cause as the priority for focused preparation.3 Infectious agent selection was based on four general criteria:

Potential for public health impact

Delivery potential (an estimation of the ease for development and dissemination, including the potential for person-to-person transmission of infection)

Public perception (fear) of the agent

Special requirements for public health preparedness (diagnostic, logistic, etc.)

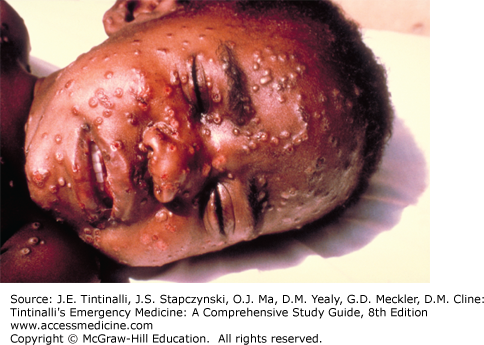

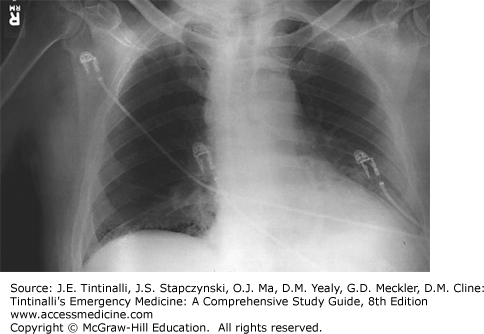

The selected agents were then ranked in three categories, based on their overall potential for adverse public health impact (Table 9-1; Figures 9-1, 9-2 and 9-3). Class A agents have the most severe potential and include viruses and bacteria such as variola major (smallpox), B. anthracis (anthrax), and Yersinia pestis (plague). Class B agents are considered to have less potential for causing widespread illness and death, and Class C agents are those that, as technology improves, could emerge as future threats. More common pathogens could be used to cause intentional injury and death, and the intentional etiology of the infections may be apparent only through epidemiologic cohort evaluation. This chapter focuses on Class A agents, but applies also to a range of additional bacteria and viruses that, although not on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention list, could have a similar human impact if used in a nefarious manner (e.g., hanta virus).

| Biologic Agent | Disease Caused | Incubation Period | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class A agents | |||

| Variola major | Smallpox (Figure 9-1) | 7–14 d | Initially fever, severe myalgias, prostration; followed within 2 d by papular rash on the face spreading to extremities (affecting palms and soles) and then to trunk (lesser extent than chickenpox); lesions progress at same rate, becoming vesicular and then pustular with subsequent scab formation |

| Bacillus anthracis | Cutaneous anthrax (Figure 9-2) | Usually 1 d, up to 2 wk reported | Macule or papule enlarging into eschar with surrounding vesicles and edema; sepsis possible, less common |

| GI anthrax | Usually 1–7 d | Abdominal pain, vomiting, GI bleeding progressing to sepsis; mesenteric adenopathy on CT | |

| Oropharyngeal anthrax | Usually 1–7 d | Sore throat, ulcers on base of tongue, marked unilateral neck swelling | |

| Inhalational anthrax (Figure 9-3) | Usually <1 wk, 43 d reported at Sverdlovsk4 | First stage is nonspecific (fever, dyspnea, cough, headache, vomiting, abdominal pain, chest pain); second stage (dyspnea, diaphoresis, shock); hemorrhagic mediastinitis with widened mediastinum on x-ray | |

| Yersinia pestis | Bubonic plague | 2–8 d | Initially fever, chills, painful swollen lymph node(s); node progresses to bubo (sometimes suppurative) |

| Pneumonic plague | 2–3 d | Fever, chills, cough, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain; clinical condition consistent with gram-negative sepsis | |

| Primary septicemic plague | 2–8 d | The clinical condition is consistent with gram-negative sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (secondary septicemic plague may occur after bubo formation) | |

| Clostridium botulinum | Foodborne botulism | 1–5 d | GI symptoms followed by symmetric cranial neuropathies, blurred vision, progressing to descending paralysis |

| Inhalational botulism* | 12–72 h | Symmetric cranial nerve palsies followed by descending paralysis | |

| Francisella tularensis | Tularemia | 1–21 d | Depends on route of exposure: all usually involve abrupt nonspecific febrile illness; inhalation exposure progressing to pleuropneumonitis; cutaneous exposure developing glandular or ulceroglandular lesions; ingestion developing oropharyngeal lesions/tonsillitis |

| Filoviruses and arenaviruses (Ebola virus) | Viral hemorrhagic fevers | 2 d–3 wk, depending on virus | Initial nonspecific febrile illness, sometimes with rash; progresses to bloody vomiting, diarrhea, shock |

| Class B agents | |||

| Coxiella burnetii | Q fever | 2–3 wk | Fever, myalgias, headache, 30% develop pneumonia, rarely lethal (2%) |

| Brucella spp. | Brucellosis | 2–4 wk | Fever, myalgias, back pain; CNS infections and endocarditis possible |

| Burkholderia mallei | Glanders | 10–14 d | Local infection: ulcers, suppurative; pneumonia, pulmonic abscesses, sepsis possible |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei | Melioidosis | 2 d to years reported | Local infection: nodule; pneumonia, pulmonic abscesses, sepsis |

| Alpha viruses (Venezuelan equine encephalitis, Eastern equine encephalitis, Western equine encephalitis) | Encephalitis | Variable | Fever, headache, aseptic meningitis, encephalitis, focal paralysis, seizures |

| Rickettsia prowazekii | Typhus fever | 7–14 d | Fever, headache, rash |

| Toxins (ricin, Staphylococcus, enterotoxin B) | Toxic syndromes | — | — |

| Chlamydia psittaci | Psittacosis | 6–19 d | Fever, headache, dry cough, pneumonia, endocarditis |

| Food safety threats (Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli O157:H7) | — | — | — |

| Water safety threats (Vibrio cholera, Cryptosporidium parvum) | — | — | — |

| Class C threats | |||

| Emerging threat agents (Nipah virus, hantavirus) | — | — | — |

CLINICAL FEATURES: RECOGNITION OF A BIOTERRORISM INCIDENT

Unless the release of an agent is openly announced or the terrorist is caught in the process of delivering the agent, initial indications of attack may be subtle. Early symptoms of most agents of concern are not readily distinguished from more common, less threatening illnesses. Fever, myalgias, and malaise could be the initial presenting symptoms of a victim of bioterrorism (anthrax and others) or of influenza, parainfluenza, or many common illnesses. This is more than a theoretical risk, as demonstrated when some agents of concern have been documented to occur in the nonbioterrorism setting.5 During the anthrax dissemination incident in 2001, several anthrax-infected postal workers were evaluated by physicians early in their illness. Their relatively nonspecific symptoms were attributed to other causes, and they were discharged home without antibiotic therapy.6 Two postal workers in this cohort died from inhalational anthrax. The similarity in early symptoms also creates another response issue: once an attack becomes public, patients with any of those common symptoms or concerns about exposure may seek rapid evaluation in EDs, clinics, or private offices. Extreme patient volume and diagnostic challenge should be anticipated.

The recognition of a biologic attack could occur through several pathways:

A patient presents with signs, symptoms, or real-time diagnostic results that obviously indicate a suspect disease process.

A patient presents with protean symptoms, but an astute clinician establishes enough criteria (e.g., suspicious historical information, signs, symptoms, short-turnaround laboratory results, public health corroborative information) to designate the patient as a presumptive case until diagnostic confirmation can be accomplished.

Patient is evaluated and admitted or released but not suspected as being a victim of bioterrorism. That patient’s course then unexpectedly worsens, or diagnostic test results (e.g., blood cultures, immunoassays), even postmortem, subsequently establish a diagnosis.

Multiple patients present over a defined period with similar symptoms or historical characteristics, with the cohort pattern raising practitioner suspicions that prompt a report to public health. Further investigation, through environmental and diagnostic testing and/or public health investigation of the cohort, establishes the cause.

Public health surveillance systems establish unusual patterns of signs, symptoms, or disease in the community and investigate further to establish the etiology.

Sampling technologies (of which there are numerous types related to different jurisdictions and agencies) detect the release of an agent of concern in the community.

Based on the few historical cases, the first three scenarios may be the most likely ways in which a bioterrorist event would be detected. Scenario 3 is how the inhalational anthrax index case was initially diagnosed in Florida during the fall of 2001.7 The initial inhalational anthrax infection in a postal worker was recognized as in scenario 2. Thus, the emergency physician should have an operational knowledge of the biologic agents of concern or understand where to readily access this information. This knowledge should include basic pathologic principles for each agent, modes of dissemination and transmission, disease signs and symptoms, recommended diagnostic testing, recommended treatment (medications, immunizations, or prophylaxis), and infection control practices (Table 9-1 and Table 9-2).8

| Biologic Agent | Vaccination | Prophylaxis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variola major |