Atrial arrhythmias

Atrial arrhythmias, the most common cardiac rhythm disturbances, result from impulses originating in the atrial tissue in areas outside the sinoatrial (SA) node. These arrhythmias can affect ventricular filling time and diminish atrial kick. The term atrial kick refers to the complete filling of the ventricles during atrial systole and normally contributes about 25% to ventricular end-diastolic volume.

Atrial arrhythmias are thought to result from three mechanisms: altered automaticity, reentry, and afterdepolarization.

Altered automaticity. The term automaticity refers to the ability of cardiac cells to initiate electrical impulses spontaneously. An increase in the automaticity of the atrial fibers can trigger abnormal impulses. Causes of increased automaticity include extracellular factors, such as hypoxia, hypocalcemia, and digoxin toxicity as well as conditions in which the function of the heart’s normal pacemaker, the SA node, is diminished. For example, increased vagal tone or hypokalemia can increase the refractory period of the SA node and allow atrial fibers to initiate impulses.

Reentry. In reentry, an impulse is delayed along a slow conduction pathway. Despite the delay, the impulse remains active enough to produce another impulse during myocardial repolarization. Reentry may occur with coronary artery disease (CAD), cardiomyopathy, or myocardial infarction (MI).

Afterdepolarization. Afterdepolarization can occur as a result of cell injury, digoxin toxicity, and other conditions. An injured cell sometimes only partially repolarizes. Partial repolarization can lead to repetitive ectopic firing called triggered activity. The depolarization produced by triggered activity, known as afterdepolarization,

can lead to atrial or ventricular tachycardia.

Atrial arrhythmias include premature atrial contractions, atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, Ashman’s phenomenon, and wandering pacemaker.

Premature atrial contractions

Premature atrial contractions (PACs) originate in the atria, outside the SA node. They arise from either a single ectopic focus or from multiple atrial foci that supersede the SA node as pacemaker for one or more beats. PACs are generally caused by enhanced automaticity in the atrial tissue. (See Recognizing PACs.)

PACs may be conducted or nonconducted (blocked) through the atrioventricular (AV) node and the rest of the heart, depending on the status of the AV and intraventricular conduction system. If the atrial ectopic pacemaker discharges too soon after the preceding QRS complex, the AV junction or bundle branches may still be refractory from conducting the previous electrical impulse. If so, they may not be repolarized enough to conduct the premature electrical impulse into the ventricles normally.

When a PAC is conducted, ventricular conduction is usually normal. Nonconducted, or blocked, PACs aren’t followed by a QRS complex. At times, it may be difficult to distinguish nonconducted PACs from SA block. (See Distinguishing nonconducted PACs from SA block, page 116.)

Causes

Alcohol, cigarettes, anxiety, fatigue, fever, and infectious diseases can trigger PACs, which commonly occur in a normal heart. Patients who eliminate or control these factors can usually correct the arrhythmia.

PACs may be associated with hyperthyroidism, coronary or valvular heart disease, acute respiratory failure, hypoxia, chronic pulmonary disease, digoxin toxicity, and certain electrolyte imbalances. PACs may also be caused by drugs that prolong the absolute refractory period of the SA node, including quinidine and procainamide (Procan).

Clinical significance

PACs are rarely dangerous in patients free from heart disease. They commonly cause no symptoms and can go unrecognized for years. Patients may perceive PACs as normal palpitations or skipped beats.

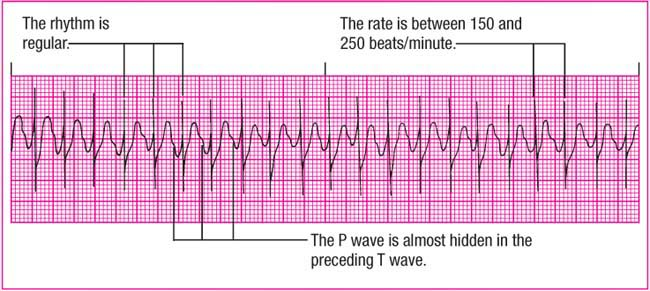

Recognizing PACs

To help you recognize premature atrial contractions (PACs), review this sample rhythm strip.

|

Rhythm: Irregular

Rate: 90 beats/minute

P wave: Abnormal with PAC; some lost in previous T wave

PR interval: 0.20 second

QRS complex: 0.08 second

T wave: Abnormal with some embedded P waves

QT interval: 0.32 second

Other: Noncompensatory pause

However, in patients with heart disease, PACs may lead to more serious arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. In a patient with acute MI, PACs can serve as an early sign of heart failure or electrolyte imbalance. PACs can also result from endogenous catecholamine release during episodes of pain or anxiety.

ECG characteristics

Rhythm: Atrial and ventricular rhythms are irregular as a result of PACs, but the underlying rhythm may be regular.

Rate: Atrial and ventricular rates vary with the underlying rhythm.

P wave: The hallmark characteristic of a PAC is a premature P wave with an abnormal configuration, when compared with a sinus P wave. Varying configurations of the P wave indicate more than one ectopic site. PACs may be hidden in the preceding T wave.

PR interval: Usually within normal limits but may be either shortened or slightly prolonged for the ectopic beat, depending on the origin of the ectopic focus.

QRS complex: Duration and configuration are usually normal when the PAC is conducted. If no QRS complex follows the PAC, the beat is called a nonconducted PAC.

T wave: Usually normal; however, if the P wave is hidden in the T wave, the T wave may appear distorted.

QT interval: Usually within normal limits.

Other: PACs may occur as a single beat, in a bigeminal (every other beat is premature), trigeminal (every third beat), or quadrigeminal (every fourth beat) pattern, or in couplets (pairs). The presence of three or more PACs in a row is called atrial tachycardia.

Look-Alikes

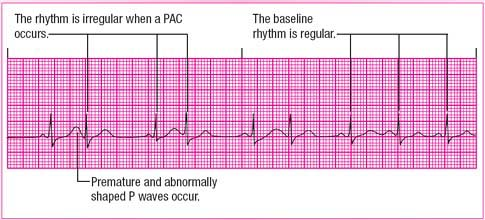

Distinguishing nonconducted PACs from SA block

To differentiate nonconducted premature atrial contractions (PACs) from sinoatrial (SA) block, follow these instructions:

Whenever you see a pause in a rhythm, look carefully for a nonconducted P wave, which may occur before, during, or just after the T wave preceding the pause.

Compare T waves that precede a pause with the other T waves in the rhythm strip, and look for a distortion of the slope of the T wave or a difference in its height or shape. These are clues showing you where the nonconducted P wave may be hidden.

If you find a P wave in the pause, check to see whether it’s premature or if it occurs earlier than subsequent sinus P waves. If it’s premature (see shaded area below, top), you can be certain it’s a nonconducted PAC.

If there’s no P wave in the pause or T wave (see shaded area below, bottom), the rhythm is SA block.

Nonconducted PAC

|

SA block

|

PACs are commonly followed by a pause as the SA node resets. The PAC depolarizes the SA node early, causing it to reset itself and disrupting the normal cycle. The next sinus beat occurs sooner than it normally would, causing a P-P interval between normal beats interrupted by a PAC to be shorter than three consecutive sinus beats, an occurrence referred to as noncompensatory.

Signs and symptoms

The patient may have an irregular peripheral or apical pulse rhythm when the PACs occur. Otherwise, the pulse rhythm and rate will reflect the underlying rhythm. Patients may complain of palpitations, skipped beats, or a fluttering sensation. In a patient with heart disease, signs and symptoms of decreased cardiac output, such as hypotension and syncope, may occur.

Interventions

Most asymptomatic patients don’t need treatment. If the patient is symptomatic, however, treatment may focus on eliminating the cause, such as caffeine and alcohol. People with frequent PACs may be treated with drugs that prolong the refractory period of the atria. Such drugs include beta-adrenergic blockers and calcium channel blockers.

When caring for a patient with PACs, assess him to help determine factors that trigger ectopic beats. Tailor patient teaching to help the patient correct or avoid underlying causes. For example, the patient might need to avoid caffeine or learn stress reduction techniques to lessen anxiety.

If the patient has ischemic or valvular heart disease, monitor for signs and symptoms of heart failure, electrolyte imbalance, and more severe atrial arrhythmias.

Atrial tachycardia

Atrial tachycardia is a supraventricular tachycardia, which means that the impulses driving the rapid rhythm originate above the ventricles. Atrial tachycardia has an atrial rate of 150 to 250 beats/minute. The rapid rate shortens diastole, resulting in a loss of atrial kick, reduced cardiac output, reduced coronary perfusion, and the potential for myocardial ischemia. (See Recognizing atrial tachycardia.)

Three forms of atrial tachycardia—atrial tachycardia with block, multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT, or chaotic atrial rhythm), and paroxysmal atrial tachycardia (PAT)—are discussed here. In MAT, the tachycardia originates from multiple foci. PAT is generally a transient event in which the tachycardia appears and disappears suddenly.

Causes

Atrial tachycardia can occur in patients with a normal heart. In these cases, it’s commonly related to excessive use of caffeine or other stimulants, marijuana use, electrolyte imbalance, hypoxia, or physical or psychological stress. Typically, however, atrial tachycardia is associated with

primary or secondary cardiac disorders, including MI, cardiomyopathy, congenital anomalies, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, and valvular heart disease.

primary or secondary cardiac disorders, including MI, cardiomyopathy, congenital anomalies, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, and valvular heart disease.

This rhythm may be a component of sick sinus syndrome. Other problems resulting in atrial tachycardia include cor pulmonale, hyperthyroidism, systemic hypertension, and digoxin toxicity (the most common cause of atrial tachycardia). (See Signs of digoxin toxicity.)

Clinical significance

In a healthy person, nonsustained atrial tachycardia is usually benign. However, this rhythm may be a forerunner of more serious ventricular arrhythmias, especially if it occurs in a patient with underlying heart disease.

The increased ventricular rate that occurs in atrial tachycardia results in decreased ventricular filling time, increased myocardial oxygen consumption, and decreased oxygen supply to the myocardium. Heart failure, myocardial ischemia, and MI can result.

ECG characteristics

Rhythm: The atrial rhythm is usually regular. The ventricular rhythm is regular or irregular, depending on the AV conduction ratio and the type of atrial tachycardia. (See Recognizing types of atrial tachycardia, pages 120 and 121.)

Rate: The atrial rate is characterized by three or more consecutive ectopic atrial beats occurring at a rate between 150 and 250 beats/minute. The rate rarely exceeds 250 beats/minute. The ventricular rate depends on the AV conduction ratio.

P wave: The P wave may be aberrant (deviating from normal appearance) or hidden in the preceding T wave. If visible, it’s usually upright and precedes each QRS complex.

PR interval: The PR interval may be unmeasurable if the P wave can’t be distinguished from the preceding T wave.

QRS complex: Duration and configuration are usually normal, unless the impulses are being conducted abnormally through the ventricles.

T wave: Usually distinguishable but may be distorted by the P wave; may be inverted if ischemia is present.

QT interval: Usually within normal limits but may be shorter because of the rapid rate.

Other: Sometimes it may be difficult to distinguish atrial tachycardia with block from sinus arrhythmia with U waves. (See Distinguishing atrial tachycardia with block from sinus arrhythmia with U waves.)

Signs of digoxin toxicity

With digoxin toxicity, atrial tachycardia isn’t the only change you might see in your patient. Be alert for the following signs and symptoms, especially if the patient is taking digoxin and his potassium level is low or he’s also taking amiodarone (because both combinations can increase the risk of digoxin toxicity):

Central nervous system: fatigue, general muscle weakness, agitation, hallucinations

Eyes: yellow-green halos around visual images, blurred vision

GI system: anorexia, nausea, vomiting

Cardiovascular system: arrhythmias (most commonly, conduction disturbances with or without atrioventricular block, premature ventricular contractions, and supraventricular arrhythmias), increased severity of heart failure, hypotension.

Remember: Digoxin’s toxic effects on the heart may be life-threatening and always require immediate attention.

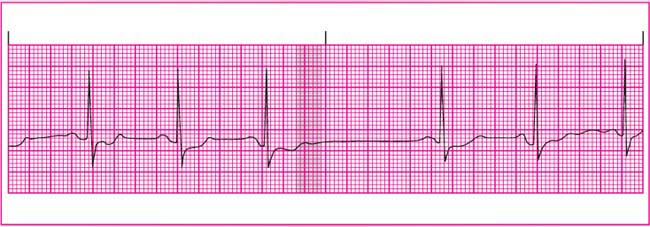

Recognizing types of atrial tachycardia

Atrial tachycardia comes in three varieties. Here’s a quick rundown of each.

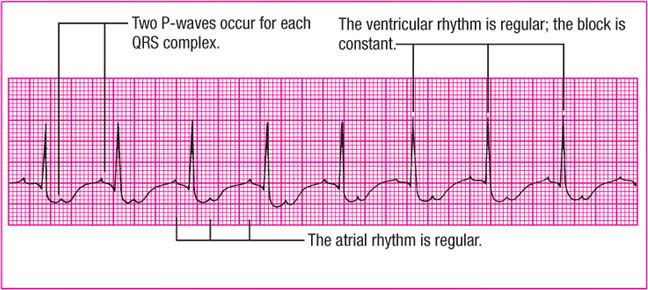

Atrial tachycardia with block

Atrial tachycardia with block is caused by increased automaticity of the atrial tissue. As the atrial rate speeds up and atrioventricular (AV) conduction becomes impaired, a 2:1 block typically occurs. Occasionally, a type I (Wenckebach) second-degree AV block may be seen.

|

Rhythm: Atrial—regular; ventricular—regular if block is constant, irregular if block is variable

Rate: Atrial—150 to 250 beats/minute, multiple of ventricular rate; ventricular—varies with block

P wave: Slightly abnormal

PR interval: Usually normal; may be hidden

QRS complex: Usually normal

T wave: Usually indistinguishable

QT interval: Indiscernible

Other: More than one P wave for each QRS complex

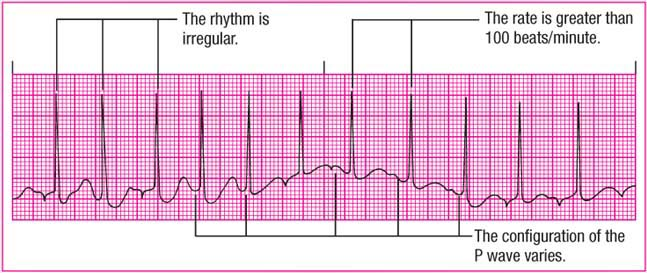

Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT)

In MAT, atrial tachycardia occurs with numerous atrial foci firing intermittently. MAT produces varying P waves on the strip and occurs most commonly in patients with chronic pulmonary diseases. The irregular baseline in the strip at the top of the next page is caused by movement of the chest wall.

|

Rhythm: Both irregular

Rate: Atrial—100 to 250 beats/minute, usually under 160; ventricular—101 to 250 beats/minute

P wave: Configuration varies; must see at least three different P wave shapes

PR interval: Variable

QRS complex: Usually normal

T wave: Usually distorted

Other: None

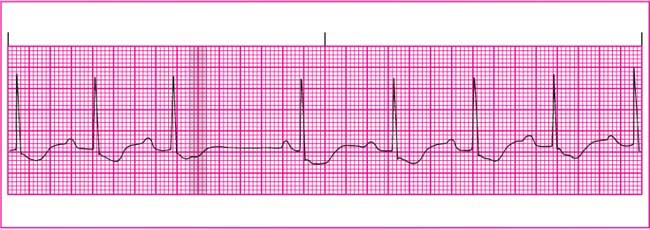

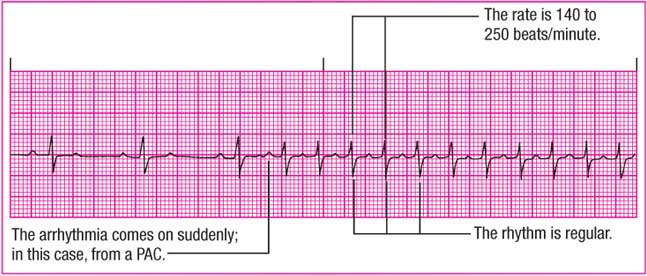

Paroxysmal atrial tachycardia (PAT)

A type of paroxysmal atrial supraventricular tachycardia, PAT features brief periods of tachycardia that alternate with periods of normal sinus rhythm. PAT starts and stops suddenly as a result of rapid firing of an ectopic focus. It commonly follows frequent premature atrial contractions (PACs), one of which initiates the tachycardia.

|

Rhythm: Regular

Rate: 140 to 250 beats/minute

P wave: Abnormal; possibly hidden in previous T wave

PR interval: Identical for each cycle

QRS complex: Possibly aberrantly conducted

T wave: Usually indistinguishable

Other: One P wave for each QRS complex

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree