Articulation Injuries of the Ankle and Hip

Robert Keith PA-C

Karen Anderson Keith PhD, RN,CS, FNP

Articulation injuries, also known as joint injuries, occur where two bones join. The injury may result from acute or chronic trauma or from the destruction of articular cartilage. This chapter focuses on the examination of an injured joint in general, and specifically on the evaluation of the ankle and hip joints. Conditions that result in or may be associated with articulation injuries of the upper extremities, lower back, and knee, or those that result from underlying degenerative or destructive processes, are discussed in separate chapters in this unit.

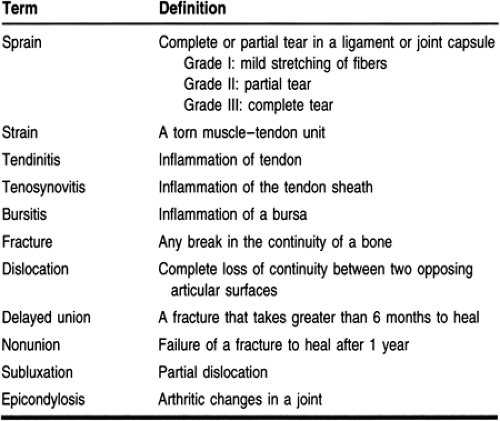

Primary care providers frequently encounter patients with articulation injuries, making basic competency in their evaluation and management a necessity. Through the relationships they have established with their patients, primary care providers are often in the best position to assess the immediate impact of acute articular injuries on the patient’s activities of daily living and social life. Also, awareness of predisposing or complicating underlying medical problems can allow nuanced management of the problem. This chapter provides an overview of how to examine an injured joint, followed by specific information on evaluating the ankle and hip. Definitions of articulation injuries are presented in Table 43-1.

GENERAL APPROACH TO THE JOINT EXAM

Some exam criteria are unique to each joint, but the following items are important in the evaluation of injury to any joint. The physical exam of the presenting joint should be undertaken as soon as feasible. As time progresses, edema, muscle spasm, pain, and joint effusion make the accurate elicitation of physical findings more difficult. The joint may also become less tractable over time, especially for injuries where closed reduction is the treatment of choice.

Inspection may reveal deformity, erythema, ecchymosis, and edema. Palpate for point tenderness, crepitus, deformity, increased warmth, and pulses. Ask the patient to move the joint through the full range of motion (active range of motion). Whether the patient is successful or unsuccessful in moving the joint, attempt passive range of motion. Motion against resistance can be used to assess neuromuscular function. Document the vascular status of the area by recording pulses and capillary refill time at a site distal to the injury.

To evaluate the functional status of a joint on physical exam, it is necessary to stress the involved joint and evaluate it for stability. In almost all cases, the differential diagnosis includes osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. When monoarticular pain is present in the absence of a clear-cut instance of trauma or gout, an infected joint is a clear possibility. Should an infected joint become prominent in the differential diagnosis, joint aspiration must be done to rule out an infectious or crystal-induced etiology.

ANKLE INJURIES

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

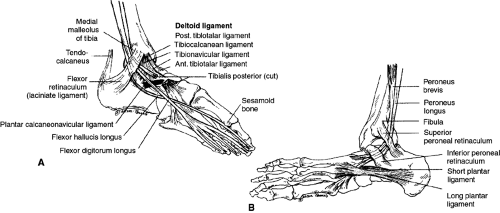

The ankle is a complex joint that carries the full weight of the body. The ankle joint is formed by the articulation of the distal ends of the tibia and fibula with the calcaneus in the foot. The ankle is composed of four major ligaments, which are of concern during acute injury. Because the overwhelming majority of ankle sprains are the result of inversion of the foot during plantar flexion, the three ligaments on the lateral aspect of the foot are most in need of evaluation. The anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) (Fig. 43-1) extends from the anterior aspect of the distal fibula to its insertion on the lateral talus. This ligament is the one most often injured when the ankle is suddenly inverted, typically while in plantar flexion. Posteriorly is the calcaneal fibular ligament (CFL), which links the posterior–inferior area of the fibula with the middle of the calcaneus. The posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL) is a short, strong, intracapsular ligament that runs posteriorly from the posterior lateral malleolus and attaches to the posterolateral surface of the talus. During inversion injuries, the ligaments are usually injured sequentially (ATFL then CFL, and finally PTFL) as increasing force is applied to invert the ankle.

On the medial side of the ankle, the deltoid ligament is a strong, five-component band that joins the distal medial malleolus of the tibia to the talus. This ligament is so strong that it often yields an avulsion fracture of the medial malleolus rather than rupture when force is applied to it in an eversion type of injury.

Epidemiology

Foot problems increase with age (Greenberg & Davis, 1993). In one study, people 65 years or older were found to have three times more problems than those between 18 and 44 (Greenberg & Davis, 1993). In this same study, during a 12-month period, 5.6 million patients over age 65 suffered from foot or ankle injuries (fracture, dislocation, sprain, or strain), a rate of 23 per 1000. No significant differences in the rates of foot and ankle injuries between women and men were found (22 and 23 per 1000, respectively); however, an unexplained higher rate of foot and ankle injuries was found in whites versus African Americans (15/1000 vs. 24/1000 in whites) (Greenberg & Davis, 1993).

Diagnostic Criteria

Fractures are ruled out with x-rays of the ankle, foot, and lower leg, as indicated by the history and physical exam. Stress testing provides the diagnosis for strains and sprains in the absence of radiographic abnormalities.

History and Physical Exam

The history should begin with questions directed at determining the mechanism of injury. How the injury occurred gives important insights about the magnitude of the forces involved and the likelihood of significant injury. Other key points include:

Did the patient hear or feel any snap or pop?

Was weight bearing or continued activity possible just after the injury?

Is there numbness or tingling in the involved extremity?

Was the onset sudden? If chronic, was it associated with a specific overuse activity?

How does the injury affect the patient’s activities of daily living?

Is the injury to the dominant limb?

General questions about overall physical activity and fitness help to situate the injury in the context of the patient’s life and anticipate the response to rehabilitation efforts. Ask about any chronic or recurrent joint pain, fever, or rash; review any medications the patient takes; check for allergies. Explore previous surgery or rehabilitation for orthopedic problems.

Patients present most commonly with a history of having had their foot inverted as a result of weight bearing on an uneven surface. The patient often describes a popping sensation when significant injury occurs. This does not necessarily mean the ligament has ruptured or a fracture is present, but it does increase the likelihood of significant injury. Injuries that are isolated to the ATFL are three times more common than injuries that include the CFL or the PTFL (Li & Meals, 1992). As a result, most ankle injuries are stable and can be treated conservatively.

Inspect the foot and ankle for edema and ecchymosis: the rapidity and extent of these conditions are helpful clues in judging the extent of injury. Careful palpation of the lateral margin of the foot over the site of the ATFL insertion will elicit pain if significant injury is present. The ability to bear weight for at least four steps has been highly correlated with grade I or II sprains. Stress testing by inverting and everting the foot has also been shown to be predictive of abnormalities on x-ray. If the foot can be inverted and has a talar tilt of less than 15°, then most likely only the ATFL is involved. If the tilt is 15° to 30°, then the ATFL and the CFL are affected. With more than 30° of tilt, all three lateral ligaments of the ankle are torn, and the risk of associated fracture is high (Seligson & Voos, 1997).

Diagnostic Studies

In the past, evaluation of a sprained ankle almost always included x-rays; however, only 15% of ankle x-rays were found to be positive for a fracture (Stiell et al, 1992). Ongoing efforts to reduce the number of unnecessary x-rays have resulted in several promising decision rules to guide x-ray usage. The Ottawa clinical decision guidelines, possibly the most widely

known, include the following:

known, include the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree