Anxiety Disorders, With an Emphasis on Panic Disorder

David S. Resch MD

Anxiety is a nonspecific symptom that is a frequent experience in life. In a large case study, 24.4% of patients described themselves as nervous people, whereas 9.3% of the population described having a panic attack during their lifetime (Robins & Reiger, 1991; Wolfe & Mase, 1994). Anxiety becomes a disorder when it impairs a person’s interpersonal, occupational, or social functioning (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994).

The APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition (DSM-IV), defines 12 types of anxiety disorders: panic disorder (PD) with agoraphobia, PD without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without history of PD, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), specific phobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress disorder (ASD), anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition, substance-induced anxiety disorder, and anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (APA, 1994).

These disorders can lead to significant disability and create a disproportionate number of office visits and medical care use. PD, GAD, OCD, and simple phobias are seen in 38.5% of primary care visits (Katon et al, 1986) and equate to 31.5% of the total costs of psychiatric disorders in the United States (Katon et al, 1992). Patients with PD have the highest rates of use of general medical, emergency, and psychiatric services of all psychiatric disorders (Katon et al, 1992).

Eighty-five percent to 88% of the time, these patients present to their primary care provider with a constellation of somatic complaints: palpitations, dizziness, shortness of breath, diarrhea, epigastric pain, chest pain, headache, hot flashes, or numbness of an extremity (Barbee et al, 1997). This variability in presentation can present a major clinical challenge to primary care providers. For example, 33% of patients with chest pain and negative angiograms suffer from PD. The extra costs of testing these patients exceed $33 million per year (Katon et al, 1992). Unnecessary emergency room visits are another cost associated with undiagnosed PD. Patients with PD may see as many as 10 different health care professionals before receiving the correct diagnosis (Katon et al, 1992).

ANXIETY DISORDERS IN GENERAL

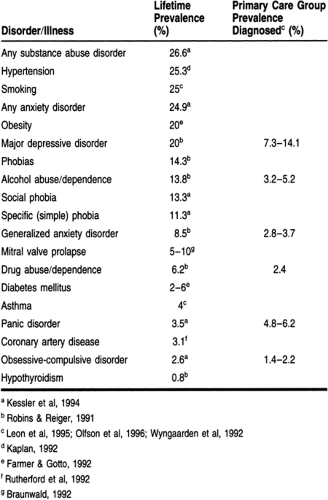

The primary care provider will care for a large number of patients with anxiety disorders. The prevalence of these will rival other illnesses traditionally expected in a primary care clinic. Table 59-1 lists the rates of incidence and prevalence for some common illnesses found a primary care clinic.

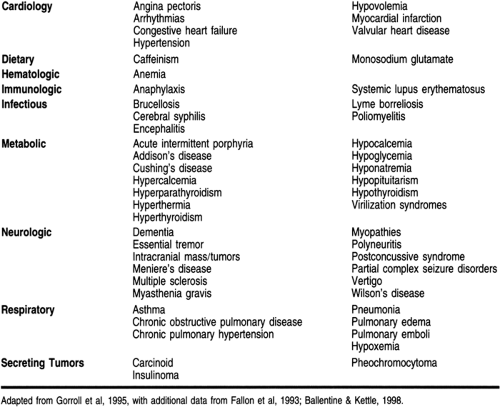

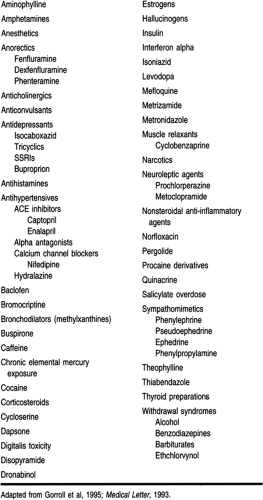

The responsibility for accurately diagnosing and subsequently treating patients requires a firm understanding of the various medical conditions and medications that can create an anxiety syndrome. The DSM-IV defines these disorders as anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition and substance-induced anxiety disorder, respectively. Tables 59-2 and 59-3 list some of the more common conditions and medications that can create anxiety.

These symptoms, individually or together, can mimic a number of medical conditions. Attempting to ascertain whether the patient’s complaints result from an underlying anxiety disorder or other medical illness is difficult. The necessary screening tests for PD include a complete blood count, urinalysis, renal and hepatic studies, measurement of serum calcium and phosphorus levels, and an electrocardiogram (Raj & Sheehan, 1987). A thorough history of symptoms and temporal profile, combined with a physical exam, can effectively rule out a majority of medications, illicit drugs, and medical conditions that can produce an anxiety syndrome. Features such as onset after age 45 years or the presence of atypical symptoms during a panic attack (eg, vertigo, loss of consciousness, loss of bladder or bowel control, headaches, slurred speech, or amnesia) suggest the possibility that a general medical condition or a substance may be causing the panic attack symptoms.

PANIC DISORDER

PD is a chronic, often debilitating condition that can have devastating effects on a person’s life, family, work, and social interactions. Because its symptoms mimic a variety of medical conditions, this disorder frequently goes undiagnosed. Fortunately, with increased education and awareness, the frequency of identification of PD has increased from 5% in 1980 to 59% in 1990. However, delayed diagnosis and high medical care use are still common (Gerdes et al, 1995).

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

Theories regarding the nature and etiology of PD range from the biologic to the psychological: false suffocation alarms, serotonin dysregulation, respiratory drive dysregulation, and locus

ceruleus dysfunction (Barlow & Lehman, 1996; Grove et al, 1997; Klein, 1993; Klein, 1996). Among the anxiety disorders, PD has been studied more often from a biologic perspective because there is an easy means of provoking panic attacks in vulnerable people: lactate infusions or inhalation of 5% to 35% CO2 (Gorman et al, 1994). However, these research efforts have failed to identify consistently the presence of a specific neuroendocrine or other neurobiologic correlate of anxiety or panic attacks.

ceruleus dysfunction (Barlow & Lehman, 1996; Grove et al, 1997; Klein, 1993; Klein, 1996). Among the anxiety disorders, PD has been studied more often from a biologic perspective because there is an easy means of provoking panic attacks in vulnerable people: lactate infusions or inhalation of 5% to 35% CO2 (Gorman et al, 1994). However, these research efforts have failed to identify consistently the presence of a specific neuroendocrine or other neurobiologic correlate of anxiety or panic attacks.

The role of genetics in PD has also been studied. Multiple family studies have found a higher rate of PD in the relatives of probands with the disorder. This finding has been seen consistently in all studies and in different countries. The risk to first-degree relatives of PD patients ranged from 2.6- to 20-fold, with a median value of 7.8 times that of the general population (Maier et al, 1993; Mendlewicz et al, 1993). Most of the studies were done on samples ascertained from treatment settings, and so this relative risk may be of a more severe form of PD.

Epidemiology

PD has been found in cultures throughout the world with prevalence rates of 0.4% to 3.5% (Weissman et al, 1997). PD without agoraphobia is diagnosed twice as often and PD with agoraphobia three times as often in women as in men. Approximately one third to one half of persons diagnosed with PD in community samples also have agoraphobia, although a much higher rate of agoraphobia is encountered in clinical samples (APA, 1994).

Age at onset for PD varies considerably but is usually between late adolescence and the mid-30s (Weissman et al, 1997). The mean age at onset of the disorder is earlier for women, at 25 to 34 years (30 to 44 years for men). The prevalence of existing cases steadily declines in age groups greater than 60 (1-month prevalence rates ranging from 0% to 0.3% compared with a peak prevalence rate of 0.7% in the 25-to-44-year-old age group) (Myers et al., 1984). In addition, illness such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can raise the risk of PD (to a level about five times that of the general population) (Karajgi et al, 1990).

Diagnostic Criteria

PD has two subtypes: with and without agoraphobia.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR PANIC DISORDER

Recurrent unexpected panic attacks

At least one of the attacks has been followed by one or more of the following for at least 1 month:

Persistent concern about having additional attacks

Worry about the implications of the attack

A significant change in behavior.

SYMPTOMATOLOGY OF PANIC ATTACKS

Shortness of breath/smothering sensations

Dizziness, unsteady feelings, or faintness

Palpitations/tachycardia

Trembling/shaking

Sweating

Choking

Nausea/abdominal distress

Depersonalization (being detached from oneself)

Derealization (feelings of unreality)

Paresthesias (numbness or tingling sensations)

Flushes/chills

Chest pain or discomfort

Fear of dying

Fear of going crazy or doing something uncontrolled.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR AGORAPHOBIA

Anxiety about being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing

Situations are avoided or else endured with significant distress.

Natural History of Illness/Comorbidity

Patients receiving ongoing, established treatments for PD show a higher rate of recovery; many of these patients continue to have mild to moderate symptoms (Barlow, 1990). Relapse rates

care high after discontinuation of effective treatment (Noyes et al, 1992), which suggests that PD is a chronic condition with a very low rate of spontaneous recovery.

care high after discontinuation of effective treatment (Noyes et al, 1992), which suggests that PD is a chronic condition with a very low rate of spontaneous recovery.

Although agoraphobia may develop at any point, its onset is usually within the first year of occurrence of recurrent panic attacks. The course of agoraphobia and its relation to the course of panic attacks are variable. In some cases, a decrease or remission of panic attacks may be followed closely by a corresponding decrease in agoraphobic avoidance and anxiety. In others, agoraphobia may become chronic regardless of the presence or absence of panic attacks (Noyes et al, 1990).

At the present state of our knowledge, there are few signs and symptoms that predict with certainty the onset of PD. The age of risk for onset extends well into middle age, with the 20th percentile at about 25 years and the median at about 35 years. The prodromal period is about 10 to 15 years long, with 20% of affected persons reporting their first panic attack at about age 14 years, and about 50% reporting a panic attack by about 20 years. The simple question, “Are you a nervous person?” would help identify more than 60% of persons with onset of PD in the next year. The occurrence of a panic attack accompanied by tachycardia would identify 45% of the cases of PD over the next year (Eaton et al, 1995).

Factors associated with increasing impairment were fewer years of education, increasing age, the presence of major depression, and a higher level of neuroticism and to a lesser extent male gender and being non-Hispanic (Hollifield et al, 1997; Karajgi et al, 1990). Patients with PD are at a higher risk than the general population for major depression, substance abuse, suicide attempts, marital problems, and financial dependency.

CLINICAL PEARL

In addition to morbidity, patients with PD also have a higher rate of death from suicide, cardiovascular disorders, and stroke.

Suicide accounts for approximately 20% of deaths of patients with PD. This rate is considerably higher than the rate for the general population (Noyes, 1991). The rate of suicide attempts in uncomplicated PD is considerably higher than in subjects with no psychiatric disorder. Even more alarming is the rate at which patients with comorbid major depression and PD kill themselves (19.5%) compared to the rate for patients with uncomplicated PD (7%) (Johnson et al, 1990).

Death from other causes is also increased in PD patients. Patients with PD had a risk of stroke twice that of persons with other psychiatric disorders or no psychiatric disorder (Weissman et al, 1990). PD has been shown to be associated with hypertension (Weissman et al, 1990), increased resting heart rate (Chignon et al, 1993; Freeman et al, 1995), increased cardiac ventricular size (Kahn et al, 1990), and decreased cerebral blood flow (Gibbs, 1992). All these physiologic changes have been theorized to play a role in the increased death rate for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events, by arguing an abnormality in the sympathetic nervous system that leads to increased reactivity and poor tonal control.

Treatment Options, Expected Outcomes, and Comprehensive Management

Treatment options can be divided into pharmacologic and psychological interventions; often these two modalities can be used concomitantly. The most common psychological interventions

are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, and psychodynamic therapy. Pharmacologic options can include benzodiazepines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, and psychodynamic therapy. Pharmacologic options can include benzodiazepines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

The provider, in consultation with the patient, should select as the initial treatment one with demonstrated efficacy. Attitudes and concerns regarding various treatment options must be explored and decisions negotiated with the patient. Patients should be educated about the disorder and encouraged to re-enter phobic situations gradually when medication alone is chosen as the initial treatment. Current practice suggests that an absence of any noticeable improvement after about 6 to 8 weeks of any treatment should lead to a reassessment, consultation, or change of modality.

COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

CBT teaches patients to anticipate the situations and bodily sensations associated with their panic attacks. This awareness sets the stage for helping the patient to control the attacks. Specially trained therapists tailor CBT to the specific needs of each patient. The therapy usually includes the following components:

Informational overview of the cycle of anxiety and the anticipation of further anxiety episodes, and rationale for the treatment

Helping patients to identify and change patterns of thinking that cause them to misperceive common events or situations as dangerous and to think the worst. For example, the therapist can help the patient to replace alarmist thoughts such as, “I’m dying” with more appropriate ones, such as “I’m hyperventilating; I can handle this.”

Teaching the patient relaxation exercises to prevent or minimize the symptoms commonly felt during a panic attack

Helping patients becomes less fearful by safely and gradually exposing them to situations they previously avoided or found frightening. This step provides an opportunity to have patients practice their coping and relaxation skills in the anxiety-provoking event.

CBT is a short-term treatment, typically lasting 12 to 15 sessions over several months. Patients who undergo CBT demonstrate a high maintenance of treatment gains over time. Follow-up studies of 1 to 3 years have found patients to be free of panic attacks at least 81% of the time (Barlow, 1997; Beck et al, 1992; Brown et al, 1997). Fifty percent to 70% of the patients maintain a high level of functioning (minimal if any disability) during this same time frame. These numbers compare to 45% with imipramine for the same time frame (Clark et al, 1994; Craske et al, 1995). Some authors have argued that such comparisons are not valid because they fail to compare the treatments in a truly double-blind fashion within a single protocol (McNally, 1996).

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Anxiety disorder patients tend to be sensitive to medication and often experience exacerbation of their symptoms with medication, especially if too large an initial dose is used. The initial treatment goal is to block the panic attacks with pharmacotherapy, then to encourage the patient to enter phobic situations to help extinguish the avoidance behavior. Pharmacotherapy should be continued for 1 year after remission of the panic attacks to prevent relapse. After 12 months, the medication can be tapered. Two thirds of the patients will not relapse immediately after cessation of pharmacotherapy (Noyes et al, 1990). CBT can improve a patient’s ability to be tapered off the drug and maintain control of symptoms at 6 months after discontinuation (Bruce et al, 1995).

Boyer (1995) performed a meta-analysis contrasting the effectiveness of the SSRIs (paroxetine, zimelidine [not available in the United States], fluvoxamine, and clomipramine) to imipramine and alprazolam in the treatment of PD. All treatments were superior to placebo in alleviating panic, and the SSRIs were superior to imipramine and alprazolam in alleviating panic.

CLINICAL PEARL

Initially, SSRIs can be panicogenic. As such, they need to be initiated at low doses and slowly tapered up. For example, the titration rate for fluoxetine should be 5 mg/day for week 1, 10 mg/day for weeks 2 through 4, and 15 to 20 mg/day for week 5 and thereafter.

The dosage of imipramine may be as low as 25 mg/day. A total imipramine plasma concentration (imipramine plus desipramine level) of 110 to 140 ng/mL or a target imipramine dose of 2.25 mg/kg/day are optimal in the acute treatment of patients with PD with agoraphobia (Mavissakalian & Perel, 1995). The drug can be initiated at 10 to 25 mg/day, which can be increased to 150 to 200 mg/day over a 2- to 4-week period. Doses of other TCAs in the management of PD are typically in the antidepressant range.

Treatment with MAOIs is usually initiated at 15 mg/day and increased by 15 mg/day every week until a positive response or a maximum of 90 mg/day. Tranylcypromine is begun at 10 mg/day in the morning. The dose is raised 10 mg/day every week until a response is seen or a maximum of 80 mg/day. Because of the dietary restrictions and significant drug–drug interactions, these medications are usually reserved for patients who do not respond to the SSRIs or TCAs.

Symptoms responding to benzodiazepines include anxiety, the frequency and severity of panic attacks, and phobic fear and avoidance. With alprazolam, the number of panic attacks per-week decreased by an average of 81% and were sometimes eliminated completely. More patients experienced moderate to marked improvement than with any other class of drugs. A decrease in anticipatory anxiety and disability at work and in family life and social life was reported. Unfortunately, a common complaint regarding the benzodiazepines is the difficulty in tapering patients off them. Slow benzodiazepine tapering results in re-emergent symptoms in 20% to 38% of patients (Sheehan & Raj, 1990).

This effect has led researchers to look at alternate agents that work on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors without the associated risk of withdrawal difficulty. Valproic acid also enhances GABA transmission. Two studies (Keck et al, 1993; Woodman & Noyes, 1994) using valproate show a 31% to 59% reduction in anxiety scores. However, these studies were not placebo-controlled, and with placebo responses of up to 50% (Cross National Collaborative Panic Study, 1992) in some studies, routine use of these agents cannot currently be recommended.

COMBINED THERAPY

Use of brief dynamic psychotherapy (15 weekly sessions) in conjunction with clomipramine therapy significantly reduces the 9-month relapse rate for PD (Wiborg & Dahl, 1996). A recent meta-analysis of studies comparing seven different treatment options (high-potency benzodiazepines, antidepressants, psychological panic management, exposure in vivo, pill-placebo combined with exposure, antidepressants combined with exposure, and psychological panic management combined with exposure in vivo) demonstrated that exposure in vivo was not effective. The remaining six treatments had the same effect in decreasing panic. Antidepressant use plus exposure in vivo was superior to all other treatments (van Balkrom et al, 1997).

CLINICAL PEARLS

To differentiate PD from other medically important conditions, the patient should have a thorough physical exam. PD symptoms can mimic those of other conditions, such as myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, hyperthyroidism, and certain types of epilepsy.

Patients may focus on only one or two symptoms as they describe the attacks, concentrating only on their physical sensations and not on the fears they experience.

Panic attacks can also be triggered by large doses of caffeine, some cold medicines, and cocaine and marijuana. If a patient has a substance abuse problem, it will have to be treated before PD can be addressed fully.

Even though panic attacks do not represent an immediate danger to the life of the patient, patients with PD have a higher death rate from vascular events.

Patients with psychiatric comorbidities should be referred for further evaluation and treatment to a psychiatrist familiar with PD.

GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER

GAD is an illness characterized by at least 6 months of persistent and excessive anxiety and worry. Adults with GAD often worry about everyday, routine life circumstances such as possible job responsibilities, finances, the health of family members, misfortune of their children, or minor matters such as household chores, car repairs, or being late for appointments. Although persons with GAD may not always identify their worry as excessive, they report objective distress from constant worry, have difficulty controlling the worry, or have related impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (APA, 1994).

Epidemiology

In clinical settings, GAD is diagnosed somewhat more frequently in women than in men (about 55% to 60% of those presenting with the disorder are female) (APA, 1994). In a community sample, the 1-year prevalence rate for GAD was approximately 3% and the lifetime prevalence rate was 5.1% to 6.6% (Robins & Reiger, 1991; Wittchen et al, 1994).

Diagnostic Criteria

Excessive anxiety and worry, occurring more days than not for the last 6 months, about a number of events or activities

Difficulty controlling the worry

The anxiety and worry are associated with three of the following six symptoms:

Restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge

Irritability

Being easily fatigued

Muscle tension

Difficulty concentrating or mind going blank

Sleep disturbance.

Natural History of Illness/Comorbidity

Most persons with GAD report feeling anxious and nervous all their lives. Although more than half those presenting for treatment report onset in childhood or adolescence, onset occurring after age 20 is not uncommon (Keller et al, 1992; Robins & Reiger, 1991). The course is chronic but fluctuating and often worsens during times of stress (Angst & Dobler-Mikola, 1991). The mean duration of the illness is reported to be about 6 to 10 years, with 40% of patients reporting durations of illness of greater than 5 years (Robins & Reiger, 1991). GAD may have a more chronic course than PD (Massion et al, 1993; Noyes et al, 1992). Thirty-one percent of patients who have a remission subsequently have another episode (Keller et al, 1992).

GAD patients report physical symptoms as often as PD patients (Barbee et al, 1997). The most common symptoms reported include palpitations, joint pain, chest pain, shortness of breath, headaches, dizziness, and excessive gas (Barbee et al, 1997; Logue et al, 1993). GAD interferes with the patient’s life substantially in 49% of cases (Wittchen et al, 1994).

The comorbidity of GAD in community samples is fairly significant. In outpatient clinics, 36% to 51% of patients with GAD also met the criteria for PD, 29% to 46% for major depressive disorder, and 17% to 29% for social phobia (Brown & Barlow, 1992; Massion et al, 1993; Noyes et al, 1992). Personality disorders have been reported to occur in 30% to 60% of patients with GAD (Noyes et al, 1992; Sanderson et al, 1994). The comorbidity with substance abuse is lower than other anxiety disorders, about 10% to 20% in clinic samples and lower in community samples (Massion et al, 1993; Noyes et al, 1992; Robins & Reiger, 1991). Overall, 90.4% of persons with a lifetime diagnosis of GAD have at least one other lifetime psychiatric diagnosis, whereas 66.3% of those with a current diagnosis of GAD had another comorbid disorder (Wittchen et al, 1994). The strongest comorbidities were found for mood disorders, PD, and agoraphobia. Because of this significant comorbidity, management of GAD can be difficult.

Treatment Options, Expected Outcomes, and Comprehensive Management

With pure GAD, patients should be asked to avoid caffeine and alcohol and stop using all possible sympathomimetic medications. If symptoms do not significantly improve with these changes, alternative treatments may be considered. Benzodiazepines have been the mainstay of treatment of GAD, but little data are present to suggest any long-term benefit of these agents. Short-term use of diazepam appears to help with the physical symptoms of anxiety but not the psychic symptoms. However, discontinuation can create rebound anxiety—anxiety that is greater than the original symptoms and not related to withdrawal effects (Pourmotabbed et al, 1996).

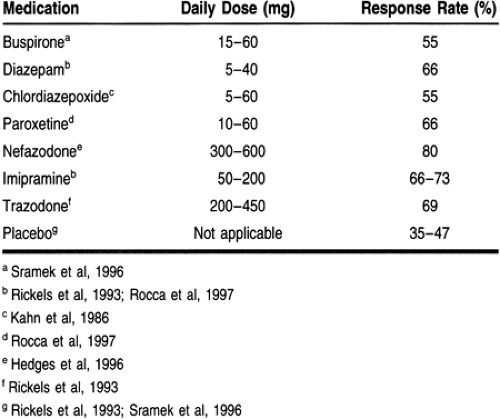

The only FDA-approved medication for the treatment of GAD is buspirone (Table 59-4). There are several studies demonstrating its efficacy in the short and long term. The best placebo-controlled trial demonstrated that buspirone at 15 to 45 mg/day produced improvement in 54.9% of patients, compared with 34.6% of patients taking placebo (Schweizer & Rickels, 1997; Sramek et al, 1996). However, patients who have been treated with benzodiazepines and then changed to buspirone are five times less likely to respond to buspirone (Schwiezer et al, 1986). This phenomenon has prompted some authors to argue for the use of buspirone in benzodiazepine-naïve patients only.

Open label trials conducted with paroxetine (Rocca et al, 1997) and nefazodone (Hedges et al, 1996) both suggested benefit in reducing the psychic anxiety associated with GAD. When anxiety symptoms present for the first time in later life, there is a high rate of comorbidity with depressive disorders. In this case, one of the antidepressants used to treat GAD should be used rather than benzodiazepines (Flint, 1997).

Cognitive and behavioral therapies and relaxation training have also demonstrated efficacy in treating GAD. Patients taught anxiety-reduction techniques showed stable or improved symptoms at 6 months of follow-up. The degree of symptom reduction exceeded the greatest reported amount for short-term benzodiazepine treatment. A comparative trial of CBT, anxiety-management training, benzodiazepines, and a wait list control demonstrated that psychological interventions produced sustained improvement and the benzodiazepine group had minimal improvement, but all were superior to the control group (Harvey & Rapee, 1995).

Referral Points and Clinical Warnings

GAD is a highly prevalent condition. The course of illness is often chronic and fluctuates in severity.

Buspirone is probably the treatment of choice when prolonged pharmacotherapy is indicated, because it does not produce physical dependence.

CBT or anxiety-management techniques may offer longer-term gains than medications. Referral to an appropriate mental health specialist may be indicated.

SSRIs and imipramine are effective in treating GAD.