Key Concepts

The rate of anesthetic complications will never be zero. All anesthesia practitioners, irrespective of their experience, abilities, diligence, and best intentions, will participate in anesthetics that are associated with patient injury.

The rate of anesthetic complications will never be zero. All anesthesia practitioners, irrespective of their experience, abilities, diligence, and best intentions, will participate in anesthetics that are associated with patient injury.

Malpractice occurs when four requirements have been met: (1) the practitioner must have a duty to the patient; (2) there must have been a breach of duty (deviation from the standard of care); (3) the patient (plaintiff) must have suffered an injury; and (4) the proximate cause of the injury must have been the practitioner’s deviation from the standard of care.

Malpractice occurs when four requirements have been met: (1) the practitioner must have a duty to the patient; (2) there must have been a breach of duty (deviation from the standard of care); (3) the patient (plaintiff) must have suffered an injury; and (4) the proximate cause of the injury must have been the practitioner’s deviation from the standard of care.

Anesthetic mishaps can be categorized as preventable or unpreventable. Of the preventable incidents, most involve human error, as opposed to equipment malfunctions.

Anesthetic mishaps can be categorized as preventable or unpreventable. Of the preventable incidents, most involve human error, as opposed to equipment malfunctions.

The relative decrease in death attributed to respiratory rather than cardiovascular damaging events has been attributed to the increased use of pulse oximetry and capnometry.

The relative decrease in death attributed to respiratory rather than cardiovascular damaging events has been attributed to the increased use of pulse oximetry and capnometry.

Many anesthetic fatalities occur only after a series of coincidental circumstances, misjudgments, and technical errors coincide (mishap chain).

Many anesthetic fatalities occur only after a series of coincidental circumstances, misjudgments, and technical errors coincide (mishap chain).

Despite differing mechanisms, anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions are typically clinically indistinguishable and equally life-threatening.

Despite differing mechanisms, anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions are typically clinically indistinguishable and equally life-threatening.

True anaphylaxis due to anesthetic agents is rare; anaphylactoid reactions are much more common. Muscle relaxants are the most common cause of anaphylaxis during anesthesia.

True anaphylaxis due to anesthetic agents is rare; anaphylactoid reactions are much more common. Muscle relaxants are the most common cause of anaphylaxis during anesthesia.

Patients with spina bifida, spinal cord injury, and congenital abnormalities of the genitourinary tract have a very increased incidence of latex allergy. The incidence of latex anaphylaxis in children is estimated to be 1 in 10,000.

Patients with spina bifida, spinal cord injury, and congenital abnormalities of the genitourinary tract have a very increased incidence of latex allergy. The incidence of latex anaphylaxis in children is estimated to be 1 in 10,000.

Although there is no clear evidence that exposure to trace amounts of anesthetic agents presents a health hazard to operating room personnel, the United States Occupational Health and Safety Administration continues to set maximum acceptable trace concentrations of less than 25 ppm for nitrous oxide and 0.5 ppm for halogenated anesthetics (2 ppm if the halogenated agent is used alone).

Although there is no clear evidence that exposure to trace amounts of anesthetic agents presents a health hazard to operating room personnel, the United States Occupational Health and Safety Administration continues to set maximum acceptable trace concentrations of less than 25 ppm for nitrous oxide and 0.5 ppm for halogenated anesthetics (2 ppm if the halogenated agent is used alone).

Hollow (hypodermic) needles pose a greater risk than do solid (surgical) needles because of the potentially larger inoculum. The use of gloves, needleless systems, or protected needle devices may decrease the incidence of some (but not all) types of injury.

Hollow (hypodermic) needles pose a greater risk than do solid (surgical) needles because of the potentially larger inoculum. The use of gloves, needleless systems, or protected needle devices may decrease the incidence of some (but not all) types of injury.

Anesthesiology is a high-risk medical specialty for substance abuse.

Anesthesiology is a high-risk medical specialty for substance abuse.

The three most important methods of minimizing radiation doses are limiting total exposure time during procedures, using proper barriers, and maximizing one’s distance from the source of radiation.

The three most important methods of minimizing radiation doses are limiting total exposure time during procedures, using proper barriers, and maximizing one’s distance from the source of radiation.

Anesthetic Complications: Introduction

The rate of anesthetic complications will never be zero. All anesthesia practitioners, irrespective of their experience, abilities, diligence, and best intentions, will participate in anesthetics that are associated with patient injury. Moreover, unexpected adverse perioperative outcomes can lead to litigation, even if those outcomes did not directly arise from anesthetic mismanagement. This chapter reviews management approaches to complications secondary to anesthesia and discusses medical malpractice and legal issues from an American (USA) perspective. Readers based in other countries may not find this section to be as relevant to their practices.

The rate of anesthetic complications will never be zero. All anesthesia practitioners, irrespective of their experience, abilities, diligence, and best intentions, will participate in anesthetics that are associated with patient injury. Moreover, unexpected adverse perioperative outcomes can lead to litigation, even if those outcomes did not directly arise from anesthetic mismanagement. This chapter reviews management approaches to complications secondary to anesthesia and discusses medical malpractice and legal issues from an American (USA) perspective. Readers based in other countries may not find this section to be as relevant to their practices.

Litigation and Anesthetic Complications

All anesthesia practitioners will have patients with adverse outcomes, and in the USA most anesthesiologists will at some point in their career be involved to one degree or another in malpractice litigation. Consequently, all anesthesia staff should expect litigation to be a part of their professional lives and acquire suitably solvent medical malpractice insurance with coverage appropriate for the community in which they practice.

When unexpected events occur, anesthesia staff must generate an appropriate differential diagnosis, seek necessary consultation, and execute a treatment plan to mitigate (to the greatest degree possible) any patient injury. Appropriate documentation in the patient record is helpful, as many adverse outcomes will be reviewed by facility-based and practice-based quality assurance and performance improvement authorities. Deviations from acceptable practice will likely be noted in the practitioner’s quality assurance file. Should an adverse outcome lead to litigation, the medical record documents the practitioner’s actions at the time of the incident. Often years pass before litigation proceeds to the point where the anesthesia provider is asked about the case in question. Although memories fade, a clear and complete anesthesiology record can provide convincing evidence that a complication was recognized and appropriately treated.

A lawsuit may be filed, despite a physician’s best efforts to communicate with the patient and family about the intraoperative events, management decisions, and the circumstances surrounding an adverse event. It is often not possible to predict which cases will be pursued by plaintiffs! Litigation may be pursued when it is clear (at least to the defense team) that the anesthesia care conformed to standards, and, conversely, that suits may not be filed when there is obvious anesthesia culpability. That said, anesthetics that are followed by unexpected death, paralysis, or brain injury of young, economically productive individuals are particularly attractive to plaintiff’s lawyers. When a patient has an unexpectedly poor outcome, one should expect litigation irrespective of one’s “positive” relationship with the patient or the injured patient’s family or guardians.

Malpractice occurs when four requirements are met: (1) the practitioner must have a duty to the patient; (2) there must have been a breach of duty (deviation from the standard of care); (3) the patient (plaintiff) must have suffered an injury; and (4) the proximate cause of the injury must have been the practitioner’s deviation from the standard of care. A duty is established when the practitioner has an obligation to provide care (doctor-patient relationship). The practitioner’s failure to execute that duty constitutes a breach of duty. Injuries can be physical, emotional, or financial. Causation is established; if but for the breach of duty, the patient would not have experienced the injury. When a claim is meritorious, the tort system attempts to compensate the injured patient and/or family members by awarding them monetary damages.

Malpractice occurs when four requirements are met: (1) the practitioner must have a duty to the patient; (2) there must have been a breach of duty (deviation from the standard of care); (3) the patient (plaintiff) must have suffered an injury; and (4) the proximate cause of the injury must have been the practitioner’s deviation from the standard of care. A duty is established when the practitioner has an obligation to provide care (doctor-patient relationship). The practitioner’s failure to execute that duty constitutes a breach of duty. Injuries can be physical, emotional, or financial. Causation is established; if but for the breach of duty, the patient would not have experienced the injury. When a claim is meritorious, the tort system attempts to compensate the injured patient and/or family members by awarding them monetary damages.

Being sued is stressful, regardless of the perceived “merits” of the claim. Preparation for defense begins before an injury has occurred. Anesthesiology staff should carefully explain the risks and benefits of the anesthesia options available to the patient. The patient grants informed consent following a discussion of the risks and benefits. Informed consent does not consist of handing the patient a form to sign. Informed consent requires that the patient understand the choices being presented. As previously noted, appropriate documentation of patient care activities, differential diagnoses, and therapeutic interventions helps to provide a defensible record of the care that was provided, resistant to the passage of time and the stress of the litigation experience.

When an adverse outcome occurs, the hospital and/or practice risk management group should be immediately notified. Likewise, one’s liability insurance carrier should be notified of the possibility of a claim for damages. Some policies have a clause that disallows the practitioner from admitting errors to patients and families. Consequently, it is important to know and obey the institution’s and insurer’s approach to adverse outcomes. Nevertheless, most risk managers advocate a frank and honest disclosure of adverse events to patients or approved family members. It is possible to express sorrow about an adverse outcome without admitting “guilt.” Ideally, such discussions should take place in the presence of risk management personnel and/or a departmental leader.

It must never be forgotten that the tort system is designed to be adversarial. Unfortunately, this makes every patient a potential courtroom adversary. Malpractice insurers will hire a defense firm to represent the anesthesia staff involved. Typically, multiple practitioners and the hospitals in which they work will be named to involve the maximal number of insurance policies that might pay in the event of a plaintiff’s victory, and to ensure that the defendants cannot choose to attribute “blame” for the adverse event to whichever person or entity was not named in the suit. In some systems (usually when everyone in a health system is insured by the same carrier), all of the named entities are represented by one defense team. More commonly, various insurers and attorneys represent specific practitioners and institutional providers. In this instance, those involved may deflect and diffuse blame from themselves and focus blame on others also named in the action. One should not discuss elements of any case with anyone other than a risk manager, insurer, or attorney, as other conversations are not protected from discovery. Discovery is the process by which the plaintiff’s attorneys access the medical records and depose witnesses under oath to establish the elements of the case: duty, breach, injury, and causation. False testimony can lead to criminal charges of perjury.

Oftentimes, expediency and financial risk exposure will argue for settlement of the case. The practitioner may or may not be able to participate in this decision depending upon the insurance policy. Settled cases are reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank and become a part of the physician’s record. Moreover, malpractice suits, settlements, and judgments must be reported to hospital authorities as part of the credentialing process. When applying for licensure or hospital appointment, all such actions must be reported. Failure to do so can lead to adverse consequences.

The litigation process begins with the delivery of a summons indicating that an action is pending. Once delivered, the anesthesia defendant must contact his or her malpractice insurer/risk management department, who will appoint legal counsel. Counsel for both the plaintiff and defense will identify “independent experts” to review the cases. These “experts” are paid for their time and expenses and can arrive at dramatically different assessments of the case materials. Following review by expert consultants, the plaintiff’s counsel may depose the principal actors involved in the case. Providing testimony can be stressful. Generally, one should follow the advice of one’s defense attorney. Oftentimes, plaintiff’s attorneys will attempt to anger or confuse the deponent, hoping to provoke a response favorable to the claim. Most defense attorneys will advise their clients to answer questions as literally and simply as possible, without offering extraneous commentary. Should the plaintiff’s attorney become abusive, the defense attorney will object for the record. However, depositions, also known as “examinations before trial,” are not held in front of a judge (only the attorneys, the deponent, the court reporter[s], and [sometimes] the videographer are present). Obligatory small talk often occurs among the attorneys and the court reporters. This is natural and should not be a source of anxiety for the defendant, because in most localities, the same plaintiff’s and defense attorneys see each other regularly.

Following discovery, the insurers, plaintiffs, and defense attorneys will “value” the case and attempt to monetize the damages. Items, such as pain and suffering, loss of consortium with spouses, lost wages, and many other factors, are included in determining what the injury is worth. Also during this period, the defense attorney may petition the court to grant defendants a “summary judgment,” dismissing the defendant from the case if there is no evidence of malpractice elicited during the discovery process. At times, the plaintiff’s attorneys will dismiss the suit against certain named individuals after they have testified, particularly when their testimony implicates other named defendants.

Settlement negotiations will occur in nearly every action. Juries are unpredictable, and both parties are often hesitant to take a case to trial. There are expenses associated with litigation, and, consequently, both plaintiff and defense attorneys will try to avoid uncertainties. Many anesthesia providers will not want to settle a case because the settlement must be reported. Nonetheless, an award in excess of the insurance policy maximum may (depending on the jurisdiction) place the personal assets of the defendant providers at risk. This underscores the importance of our advice to all practitioners (not only those involved in a lawsuit) to assemble their personal assets (house, retirement fund, etc.) in a fashion that makes personal asset confiscation difficult in the event of a negative judgment. One should remember that an adverse judgment may arise from a case in which most anesthesiologists would find the care to meet acceptable standards!

When a case proceeds to trial, the first step is jury selection in the process of voir dire—from the French—“to see, to say.” In this process, attorneys for the plaintiff and defendant will use various profiling techniques to attempt to identify (and remove) jurors who are less likely to be sympathetic to their case, while keeping the jurors deemed most likely to favor their side. Each attorney is able to strike a certain number of jurors from the pool because they perceive an inherent bias. The jurors will be questioned about such matters as their educational level, history of litigation themselves, professions, and so forth.

Following empanelment, the case is presented to the jury. Each attorney attempts to educate the jurors—who usually have limited knowledge of healthcare (physicians and nurses will usually be struck from the jury)—as to the standard of care for this or that procedure and how the defendants did or did not breach their duty to the patient to uphold those standards. Expert witnesses will attempt to define what the standard of care is for the community, and the plaintiff and defendant will present experts with views that are favorable to their respective cause. The attorneys will attempt to discredit the opponent’s experts and challenge their opinions. Exhibits are often used to explain to the jury what should or should not have happened and why the injuries for which damages are being sought were caused by the practitioner’s negligence.

After the attorneys conclude their closing remarks, the judge will “charge” the jurors with their duty and will delineate what they can consider in making their judgment. Once a case is in the hands of a jury, anything can happen. Many cases will settle during the course of the trial, as neither party wishes to be subject to the arbitrary decisions of an unpredictable jury. Should the case not settle, the jurors will reach a verdict. When a jury determines that the defendants were negligent and negligence was the cause of the plaintiff’s injuries, the jury will determine an appropriate award. If the award is so egregiously large that it is inconsistent with awards for similar injuries, the judge may reduce its amount. Of course, following any verdict, there are numerous appeals that may be filed. It is important to note that appeals typically do not relate to the medical aspects of the case, but are filed because the trial process itself was somehow flawed.

Unfortunately, a malpractice action can take years to reach a conclusion. Consultation with a mental health professional may be appropriate for the defendant when the litigation process results in unmanageable stress, depression, increased alcohol consumption, or substance abuse.

Determining what constitutes the “standard of care” is increasingly complicated. In the United Sates, the definition of “standard of care” is made separately by each state. The standard of care is NOT necessarily “best practices” or even the care that another physician would prefer. Generally, the standard of care is met when a patient receives care that other reasonable physicians in similar circumstances would regard as adequate. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has published standards, and these provide a basic framework for routine anesthetic practice (eg, monitoring). Increasingly, a number of “guidelines” have been developed by the multiple specialty societies to identify best practices in accordance with assessments of the evidence in the literature. The increasing number of guidelines proffered by the numerous anesthesia and other societies and their frequent updating can make it difficult for clinicians to stay abreast of the changing nature of practice. This is a particular problem when two societies produce conflicting guidelines on the same topic using the same data. Likewise, the information upon which guidelines are based can range from randomized clinical trials to the opinion of “experts” in the field. Consequently, guidelines do not hold the same weight as standards. Guidelines produced by reputable societies will generally include an appropriate disclaimer based on the level of evidence used to generate the guideline. Nonetheless, plaintiff’s attorneys will attempt to use guidelines to establish a “standard of care,” when, in fact, clinical guidelines are prepared to assist in guiding the delivery of therapy. However, if deviation from guidelines is required for good patient care, the rationale for such actions should be documented on the anesthesia record, as plaintiff’s attorneys will attempt to use the guideline as a de facto standard of care.

Adverse Anesthetic Outcomes

There are several reasons why it is difficult to accurately measure the incidence of adverse anesthesia-related outcomes. First, it is often difficult to determine whether the cause of a poor outcome is the patient’s underlying disease, the surgical procedure, or the anesthetic management. In some cases, all three factors contribute to a poor outcome. Clinically important measurable outcomes are relatively rare after elective anesthetics. For example, death is a clear endpoint, and perioperative deaths do occur with some regularity. But, because deaths attributable to anesthesia are much rarer, a very large series of patients must be studied to assemble conclusions that have statistical significance. Nonetheless, many studies have attempted to determine the incidence of complications due to anesthesia. Unfortunately, studies vary in criteria for defining an anesthesia-related adverse outcome and are limited by retrospective analysis.

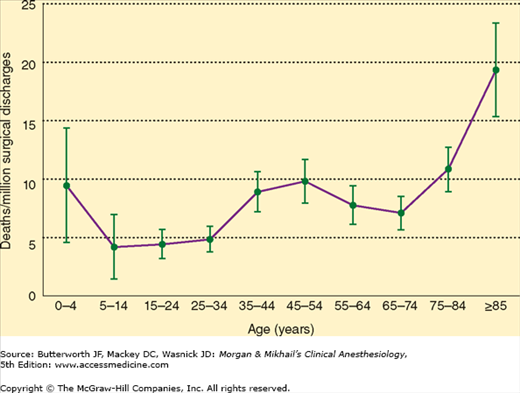

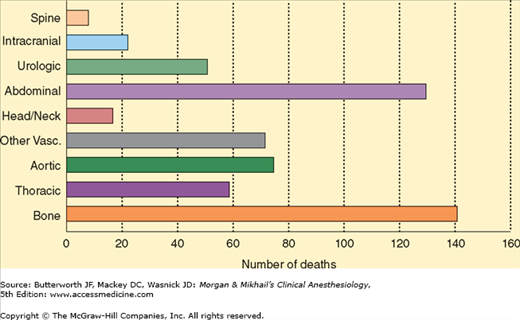

Perioperative mortality is usually defined as death within 48 hr of surgery. It is clear that most perioperative fatalities are due to the patient’s preoperative disease or the surgical procedure. In a study conducted between 1948 and 1952, anesthesia mortality in the United States was approximately 5100 deaths per year or 3.3 deaths per 100,000 population. A review of cause of death files in the United States showed that the rate of anesthesia-related deaths was 1.1/1,000,000 population or 1 anesthetic death per 100,000 procedures between 1999 and 2005 (Figure 54-1). These results suggest a 97% decrease in anesthesia mortality since the 1940s. However, a 2002 study reported an estimated rate of 1 death per 13,000 anesthetics. Due to differences in methodology, there are discrepancies in the literature as to how well anesthesiology is doing in achieving safe practice. In a 2008 study of 815,077 patients (ASA class 1, 2, or 3) who underwent elective surgery at US Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, the mortality rate was 0.08% on the day of surgery. The strongest association with perioperative death was the type of surgery (Figure 54-2). Other factors associated with increased risk of death included dyspnea, reduced albumin concentrations, increased bilirubin, and increased creatinine concentrations. A subsequent review of the 88 deaths that occurred on the surgical day noted that 13 of the patients might have benefitted from better anesthesia care, and estimates suggest that death might have been prevented by better anesthesia practice in 1 of 13,900 cases. Additionally, this study reported that the immediate postsurgical period tended to be the time of unexpected mortality. Indeed, often missed opportunities for improved anesthetic care occur following complications when “failure to rescue” contributes to patient demise.

Figure 54-1

Annual in-hospital anesthesia-related deaths rates per million hospital surgical discharges and 95% confidence intervals by age, United States, 1999-2005. (Reproduced, with permission, from Li G, Warner M, Lang B, et al: Epidemiology of anesthesia-related mortality in the United States 1999-2005. Anesthesiology 2009;110:759.)

The goal of the ASA Closed Claims Project is to identify common events leading to claims in anesthesia, patterns of injury, and strategies for injury prevention. It is a collection of closed malpractice claims that provides a “snapshot” of anesthesia liability rather than a study of the incidence of anesthetic complications, as only events that lead to the filing of a malpractice claim are considered. The Closed Claims Project consists of trained physicians who review claims against anesthesiologists represented by some US malpractice insurers. The number of claims in the database continues to rise each year as new claims are closed and reported. The claims are grouped according to specific damaging events and complication type. Closed Claims Project analyses have been reported for airway injury, nerve injury, awareness, and so forth. These analyses provide insights into the circumstances that result in claims; however, the incidence of a complication cannot be determined from closed claim data, because we know neither the actual incidence of the complication (some with the complication may not file suit), nor how many anesthetics were performed for which the particular complication might possibly develop. Other similar analyses have been performed in the United Kingdom, where National Health Service (NHS) Litigation Authority claims are reviewed.

Anesthetic mishaps can be categorized as preventable or unpreventable. Examples of the latter include sudden death syndrome, fatal idiosyncratic drug reactions, or any poor outcome that occurs despite proper management. However, studies of anesthetic-related deaths or near misses suggest that many accidents are preventable. Of these preventable incidents, most involve human error (Table 54-1), as opposed to equipment malfunctions (Table 54-2). Unfortunately, some rate of human error is inevitable, and a preventable accident is not necessarily evidence of incompetence. During the 1990s, the top three causes for claims in the ASA Closed Claims Project were death (22%), nerve injury (18%), and brain damage (9%). In a 2009 report based on an analysis of NHS litigation records, anesthesia-related claims accounted for 2.5% of total claims filed and 2.4% of the value of all NHS claims. Moreover, regional and obstetrical anesthesia were responsible for 44% and 29%, respectively, of anesthesia-related claims filed. The authors of the latter study noted that there are two ways to examine data related to patient harm: critical incident and closed claim analyses. Clinical (or critical) incident data consider events that either cause harm or result in a “near-miss.” Comparison between clinical incident datasets and closed claims analyses demonstrates that not all critical events generate claims and that claims may be filed in the absence of negligent care. Consequently, closed claims reports must always be considered in this context.

Anesthetic mishaps can be categorized as preventable or unpreventable. Examples of the latter include sudden death syndrome, fatal idiosyncratic drug reactions, or any poor outcome that occurs despite proper management. However, studies of anesthetic-related deaths or near misses suggest that many accidents are preventable. Of these preventable incidents, most involve human error (Table 54-1), as opposed to equipment malfunctions (Table 54-2). Unfortunately, some rate of human error is inevitable, and a preventable accident is not necessarily evidence of incompetence. During the 1990s, the top three causes for claims in the ASA Closed Claims Project were death (22%), nerve injury (18%), and brain damage (9%). In a 2009 report based on an analysis of NHS litigation records, anesthesia-related claims accounted for 2.5% of total claims filed and 2.4% of the value of all NHS claims. Moreover, regional and obstetrical anesthesia were responsible for 44% and 29%, respectively, of anesthesia-related claims filed. The authors of the latter study noted that there are two ways to examine data related to patient harm: critical incident and closed claim analyses. Clinical (or critical) incident data consider events that either cause harm or result in a “near-miss.” Comparison between clinical incident datasets and closed claims analyses demonstrates that not all critical events generate claims and that claims may be filed in the absence of negligent care. Consequently, closed claims reports must always be considered in this context.

|

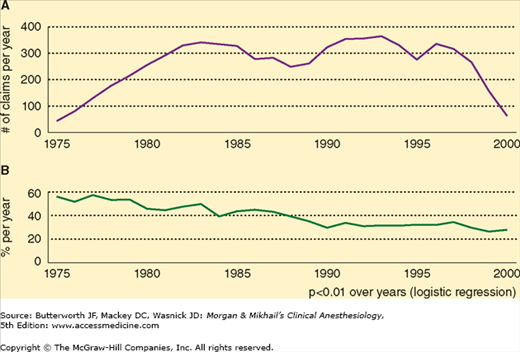

Mortality and Brain Injury

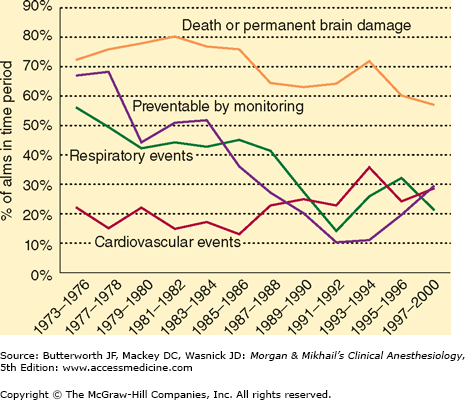

Trends in anesthesia-related death and brain damage have been tracked for many years. In a Closed Claims Project report examining claims in the period between 1975 and 2000, there were 6750 claims (Figure 54-3A and B), 2613 of which were for brain injury or death. The proportion of claims for brain injury or death was 56% in 1975, but had decreased to 27% by 2000. The primary pathological mechanisms by which these outcomes occurred were related to cardiovascular or respiratory problems. Early in the study period, respiratory-related damaging events were responsible for more than 50% of brain injury/death claims, whereas cardiovascular-related damaging events were responsible for 27% of such claims; however, by the late 1980s, the percentage of damaging events related to respiratory issues had decreased, with both respiratory and cardiovascular events being equally likely to contribute to severe brain injury or death. Respiratory damaging events included difficult airway, esophageal intubation, and unexpected extubation. Cardiovascular damaging events were usually multifactorial. Closed claims reviewers found that anesthesia care was substandard in 64% of claims in which respiratory complications contributed to brain injury or death, but in only 28% of cases in which the primary mechanism of patient injury was cardiovascular in nature. Esophageal intubation, premature extubation, and inadequate ventilation were the primary mechanisms by which less than optimal anesthetic care was thought to have contributed to patient injury related to respiratory events.  The relative decrease in causes of death being attributed to respiratory rather cardiovascular damaging events during the review period was attributed to the increased use of pulse oximetry and capnometry. Consequently, if expired gas analysis was judged to be adequate, and a patient suffered brain injury or death, a cardiovascular event was more likely to be considered causative.

The relative decrease in causes of death being attributed to respiratory rather cardiovascular damaging events during the review period was attributed to the increased use of pulse oximetry and capnometry. Consequently, if expired gas analysis was judged to be adequate, and a patient suffered brain injury or death, a cardiovascular event was more likely to be considered causative.

Figure 54-3

A: The total number of claims by the year of injury. Retrospective data collection began in 1985. Data in this analysis includes data collected through December 2003. B: Claims for death or permanent brain damage as percentage of total claims per year by year of injury. (Reproduced, with permission, from Cheney FW, Domino KB, Caplan RA, Posner KL: Nerve injury associated with anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 1999;90:1062.)

A 2010 study examining the NHS Litigation Authority dataset noted that airway-related claims led to higher awards and poorer outcomes than did nonairway-related claims. Indeed, airway manipulation and central venous catheterization claims in this database were most associated with patient death. Trauma to the airway also generates significant claims if esophageal or tracheal rupture occur. Postintubation mediastinitis should always be considered whenever there are repeated unsuccessful airway manipulations, as early intervention presents the best opportunity to mitigate any injuries incurred.

Vascular Cannulation

Claims related to central venous access in the ASA database were associated with patient death 47% of the time and represented 1.7% of the 6449 claims reviewed. Complications secondary to guidewire or catheter embolism, tamponade, bloodstream infections, carotid artery puncture, hemothorax, and pneumothorax all contributed to patient injury. Although guidewire and catheter embolisms were associated with generally lower level patient injuries, these complications were generally attributed to substandard care. Tamponade claims following line placement were often for patient death. The authors of a 2004 closed claims analysis recommended reviewing the chest radiograph following line placement and repositioning lines found in the heart or at an acute angle to reduce the likelihood of tamponade. Brain damage and stroke are associated with claims secondary to carotid cannulation. Multiple confirmatory methods should be used to ensure that the internal jugular and not the carotid artery is cannulated.

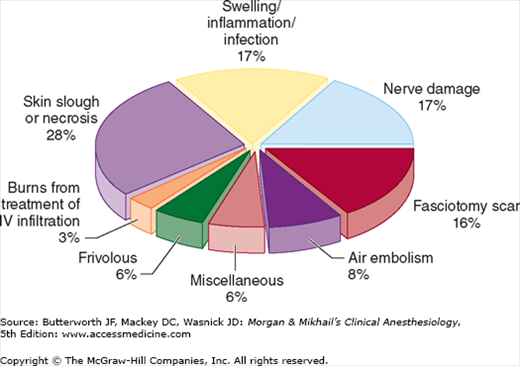

Claims related to peripheral vascular cannulation in the ASA database accounted for 2% of 6849 claims, 91% of which were for complications secondary to the extravasation of fluids or drugs from peripheral intravenous catheters that resulted in extremity injury (Figure 54-4). Air embolisms, infections, and vascular insufficiency secondary to arterial spasm or thrombosis also resulted in claims. Of interest, intravenous catheter claims in patients who had undergone cardiac surgery formed the largest cohort of claims related to peripheral intravenous catheters, most likely due to the usual practice of tucking the arms alongside the patient during the procedure, placing them out of view of the anesthesia providers. Radial artery catheters seem to generate few closed claims; however, femoral artery catheters can lead to greater complications and potentially increased liability exposure.

Obstetric Anesthesia

Both critical incident and closed claims analyses have been reported regarding complications and mortality related to obstetrical anesthesia.

In a study reviewing anesthesia-related maternal mortality in the United States using the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, which collects data on all reported deaths causally related to pregnancy, 86 of the 5946 pregnancy-related deaths reported to the Centers for Disease Control were thought to be anesthesia related or approximately 1.6% of total pregnancy related-deaths in the period 1991-2002. The anesthesia mortality rate in this period was 1.2 per million live births, compared with 2.9 per million live births in the period 1979-1990. The decline in anesthesia-related maternal mortality may be secondary to the decreased use of general anesthesia in parturients, reduced concentrations of bupivacaine in epidurals, improved airway management protocols and devices, and greater use of incremental (rather than bolus) dosing of epidural catheters.

In a 2009 study examining the epidemiology of anesthesia-related complications in labor and delivery in New York state in the period 2002-2005, an anesthesia-related complication was reported in 4438 of 957,471 deliveries (0.46%). The incidence of complications was increased in patients undergoing cesarean section, those living in rural areas, and those with other medical conditions. Complications of neuraxial anesthesia (eg, postdural puncture headache) were most common, followed by systemic complications, including aspiration or cardiac events. Other reported problems related to anesthetic dose administration and unintended overdosages. African American women and those aged 40-55 years were more likely to experience systemic complications, whereas Caucasian women and those aged 30-39 were more likely to experience complications related to neuraxial anesthesia.

ASA Closed Claims Project analyses were reported in 2009 for the period 1990-2003. Four hundred twenty-six claims from this period were compared with 190 claims in the database prior to 1990. After 1990, the proportion of claims for maternal or fetal demise was lower than that recorded prior to 1990. After 1990, the number of claims for maternal nerve injury increased. In the review of claims in which anesthesia was thought to have contributed to the adverse outcome, anesthesia delay, poor communication, and substandard care were thought to have resulted in poor newborn outcomes. Prolonged attempts to secure neuraxial blockade in the setting of emergent cesarean section can contribute to adverse fetal outcome. Additionally, the closed claims review indicated that poor communication between the obstetrician and the anesthesiologist regarding the urgency of newborn delivery was likewise thought to have contributed to newborn demise and neonatal brain injury.

Maternal death claims were secondary to airway difficulty, maternal hemorrhage, and high neuraxial blockade. The most common claim associated with obstetrical anesthesia was related to nerve injury following regional anesthesia. Nerve injury can be secondary to neuraxial anesthesia and analgesia, but also due to obstetrical causes. Early neurological consultation to identify the source of nerve injury is suggested to discern if injury could be secondary to obstetrical rather than anesthesia interventions.

Regional Anesthesia

In a closed claims analysis, peripheral nerve blocks were involved in 159 of the 6894 claims analyzed. Peripheral nerve block claims were for death (8%), permanent injuries (36%), and temporary injuries (56%). The brachial plexus was the most common location for nerve injury. In addition to ocular injury, cardiac arrest following retrobulbar block contributed to anesthesiology claims. Cardiac arrest and epidural hematomas are two of the more common damaging events leading to severe injuries related to regional anesthesia. Neuraxial hematomas in both obstetrical and nonobstetrical patients were associated with coagulopathy (either intrinsic to the patient or secondary to medical interventions). In one study, cardiac arrest related to neuraxial anesthesia contributed to roughly one-third of the death or brain damage claims in both obstetrical and nonobstetrical patients. Accidental intravenous injection and local anesthesia toxicity also contributed to claims for brain injury or death.

Nerve injuries constitute the third most common source of anesthesia litigation. A retrospective review of patient records and a claims database showed that 112 of 380,680 patients (0.03%) experienced perioperative nerve injury. Patients with hypertension and diabetes and those who were smokers were at increased risk of developing perioperative nerve injury. Perioperative nerve injuries may result from compression, stretch, ischemia, other traumatic events, and unknown causes. Improper positioning can lead to nerve compression, ischemia, and injury, however not every nerve injury is the result of improper positioning. The care received by patients with ulnar nerve injury was rarely judged to be inadequate in the ASA Closed Claims database. Even awake patients undergoing spinal anesthesia have been reported to experience upper extremity injury. Moreover, many peripheral nerve injuries do not become manifest until more than 48 hr after anesthesia and surgery, suggesting that some nerve damage that occurs in surgical patients may arise from events taking place after the patient leaves the operating room setting.

Pediatric Anesthesia

In a 2007 study reviewing 532 claims in pediatric patients aged <16 years in the ASA Closed Claims database from 1973-2000 (Figure 54-5), a decrease in the proportion of claims for death and brain damage was noted over the three decades. Likewise, the percentage of claims related to respiratory events also was reduced. Compared with before 1990, the percentage of claims secondary to respiratory events decreased during the years 1990-2000, accounting for only 23 % of claims in the latter study years compared with 51% of claims in the 1970s. Moreover, the percentage of claims that could be avoided by better monitoring decreased from 63% in the 1970s to 16% in the 1990s. Death and brain damage constitute the major complications for which claims are filed. In the 1990s, cardiovascular events joined respiratory complications in sharing the primary causes of pediatric anesthesia litigation. In the study mentioned above, better monitoring and newer airway management techniques may have reduced the incidence of respiratory events leading to litigation-generating complications in the latter years of the review period. Additionally, the possibility of a claim being filed secondary to death or brain injury is greater in children who are in ASA classes 3, 4, or 5.

In a review of the Pediatric Perioperative Cardiac Arrest Registry, which collects information from about 80 North American institutions that provide pediatric anesthesia, 193 arrests were reported in children between 1998 and 2004. During the study period, 18% of the arrests were “drug related,” compared with 37% of all arrests during the years 1994-1997. Cardiovascular arrests occurred most often (41%), with hypovolemia and hyperkalemia being the most common causes. Respiratory arrests (27%) were most commonly associated with laryngospasm. Central venous catheter placement with resultant vascular injury also contributed to some perioperative arrests. Arrests from cardiovascular causes occurred most frequently during surgery, whereas arrests from respiratory causes tended to occur after surgery. The reduced use of halothane seems to have decreased the incidence of arrests secondary to medication administration. However, hyperkalemia and electrolyte disturbances associated with transfusion and hypovolemia also contribute to sources of cardiovascular arrest in children perioperatively.

A review of data from the Pediatric Perioperative Cardiac Arrest Registry with a focus on children with congenital heart disease found that such children were more likely to arrest perioperatively secondary to a cardiovascular cause. In particular, children with a single ventricle were at increased risk of perioperative arrest. Children with aortic stenosis and cardiomyopathy were similarly found to be at increased risk of cardiac arrest perioperatively.

Out Of the Operating Room Anesthesia and Monitored Anesthesia Care

Review of the ASA Closed Claims Project database indicates that anesthesia at remote (out of the operating room) locations poses a risk to patients secondary to hypoventilation and excessive sedation. Remote location anesthesia care was more likely than operating room anesthesia care to involve a claim for death (54% vs 29%, respectively). The endoscopy suite and cardiac catheterization laboratory were the most frequent locations from which claims were generated. Monitored Anesthesia Care (MAC) was the most common technique employed in these claims. Overwhelmingly, adverse respiratory events were most frequently responsible for the injury.

An analysis of the ASA Closed Claims Project database focusing on MAC likewise revealed that oversedation and respiratory collapse most frequently lead to claims. Claims for burn injuries suffered in operating room fires were also found in the database. Supplemental oxygen, draping, pooling of flammable antiseptic preparatory solutions, and surgical cautery combine to produce the potential for operating room fires.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree