TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

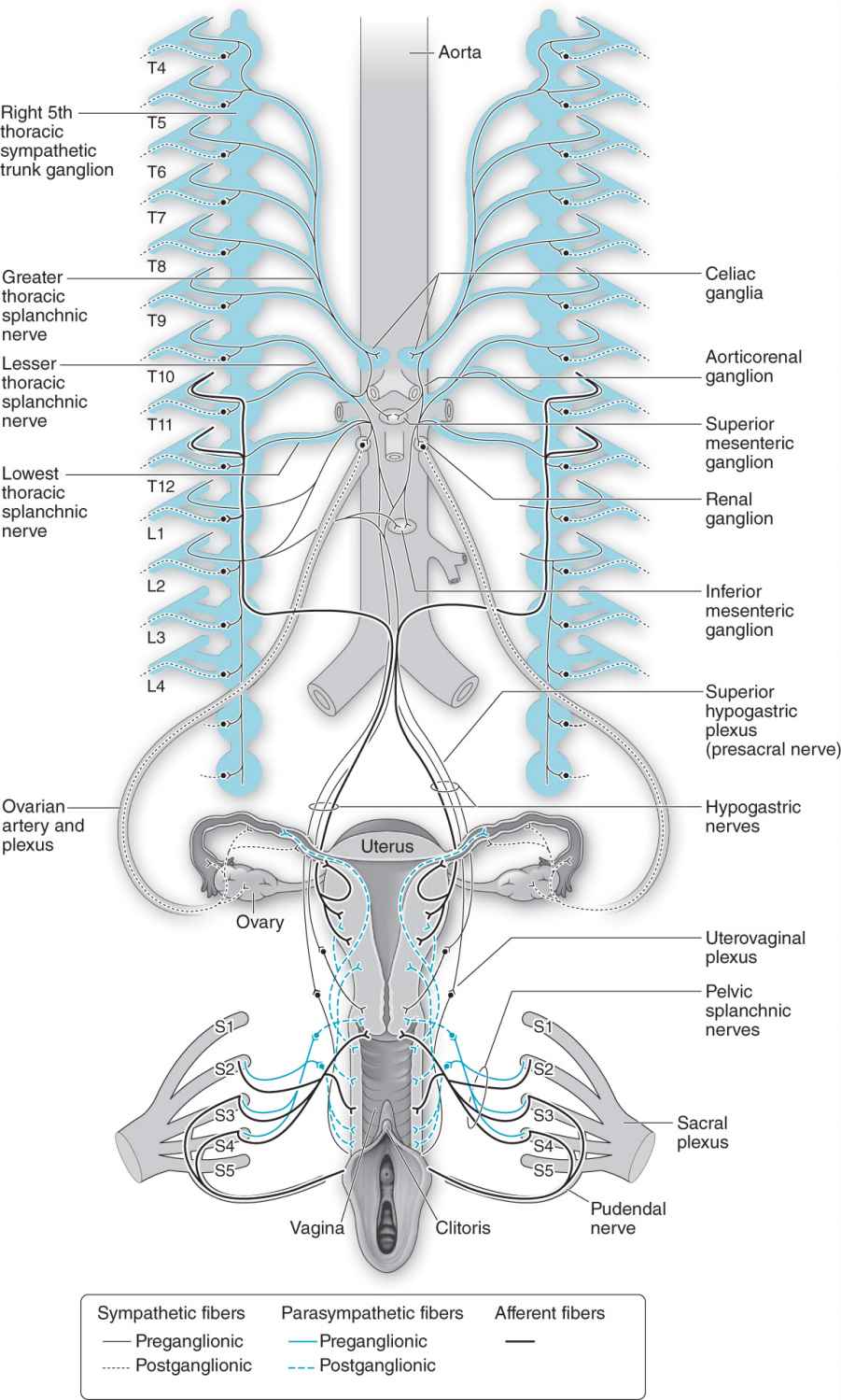

Clinical obstetric anesthesia is most commonly associated with delivery of an infant; however, there are a number of other obstetric procedures and surgeries where the use of anesthesia can optimize maternal and fetal outcomes. Miscarriage or termination of pregnancy may occur in up to 30% of pregnancies, and when accompanied by retained fetal or placental tissues, removal is accomplished with a dilation and curettage (D&C) or dilation and evacuation (D&E); these typically occur within the first 12 weeks following conception. Between 1% and 2% of pregnancies are associated with an incompetent cervix; a minority of these cases will require cervical cerclage, which is typically placed during the second trimester. Percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (PUBS) is most commonly performed in the second or third trimester for fetal indications, and late in the third trimester, external cephalic version may be attempted to turn a breech fetus into the cephalic position. Tubal ligations are most frequently performed within the first 48 hours’ postpartum, with a second peak occurrence at 6 to 8 weeks’ postpartum, when most of the pregnancy-related changes have resolved. Knowledge of the anatomic and physiologic alterations with different stages of pregnancy, as well as the relevant innervation (Figure 13-1), can optimize the planning and conduct of anesthesia; such knowledge will improve the ability of these procedures to be conducted safely and successfully, and augment the patients’ experience, comfort, and satisfaction.

Figure 13-1. Innervation (and relevant obstetric procedure) of the female reproductive organs. The fallopian tubes (tubal ligation) are innervated by T11–L1 via the hypogastric nerves. The uterus (cerclage, dilation and curettage or dilation and evacuation, and external cephalic version) is innervated by T10–L1 and S2–S4 by the uterovaginal and sacral plexus. The umbilical cord (percutaneous umbilical blood sampling) has been observed to be devoid of innervation. Relevant sensory blockade by local, regional, or neuraxial anesthesia techniques may need to include additional sensory levels to account for the placement of surgical instrumentation and the possibility for referred pain.

POSTPARTUM TUBAL LIGATION

Tubal ligation is a highly effective form of permanent sterilization and is among the most popular methods of contraception in the United States. Data from the National Survey of Family Growth for the 2006-2008 period showed that 21% of married women have undergone a tubal ligation procedure.1 However, there has been a recent decline in tubal sterilization rate, possibly explained by improved alternative long-acting and reversible methods of contraception.

Timing

Tubal ligation can be performed either in the immediate postpartum period or at any time unrelated to pregnancy (ie, interval sterilization). Tubal sterilization in the early postpartum period has several advantages over an interval sterilization:

• The uterine fundus remains at the level of the umbilicus for several days postpartum, allowing for easy access to the fallopian tubes directly beneath the abdominal wall through a small subumbilical incision.

• The cost and inconvenience of a second hospital visit can be avoided.

A possible disadvantage of performing postpartum tubal ligation (PPTL) is:

• There is a higher probability of regret in these women than in women who undergo interval sterilization,2,3 because there may be inadequate time to fully assess the newborn.

PPTL is often requested immediately after delivery, especially when the patient has a functioning labor epidural catheter. However, if the newborn requires resuscitation or is unexpectedly transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit, tubal ligation should be delayed. In addition, a tubal ligation should not be performed at a time when it might compromise other aspects of patient care.3,4

Preoperative Evaluation

All patients require a thorough preoperative assessment prior to the procedure. For immediate PPTL, the patient’s hemodynamic status and uterine tone should be evaluated carefully because blood loss is often underestimated during delivery.5 Patients should have fasted for 6 to 8 hours, depending on the type of food ingested, and aspiration prophylaxis should be considered.4 Gastric emptying of solids is delayed during labor and in the postpartum period; in contrast, gastric emptying of clear liquids is not delayed in the peripartum period unless opioids are administered during labor.6–9

Anesthetic Management

Neuraxial anesthesia is preferred to general anesthesia for most tubal ligations.4 Choice of neuraxial technique will depend on the existence of a functional epidural catheter and the interval from delivery to tubal ligation.

EPIDURAL ANESTHESIA

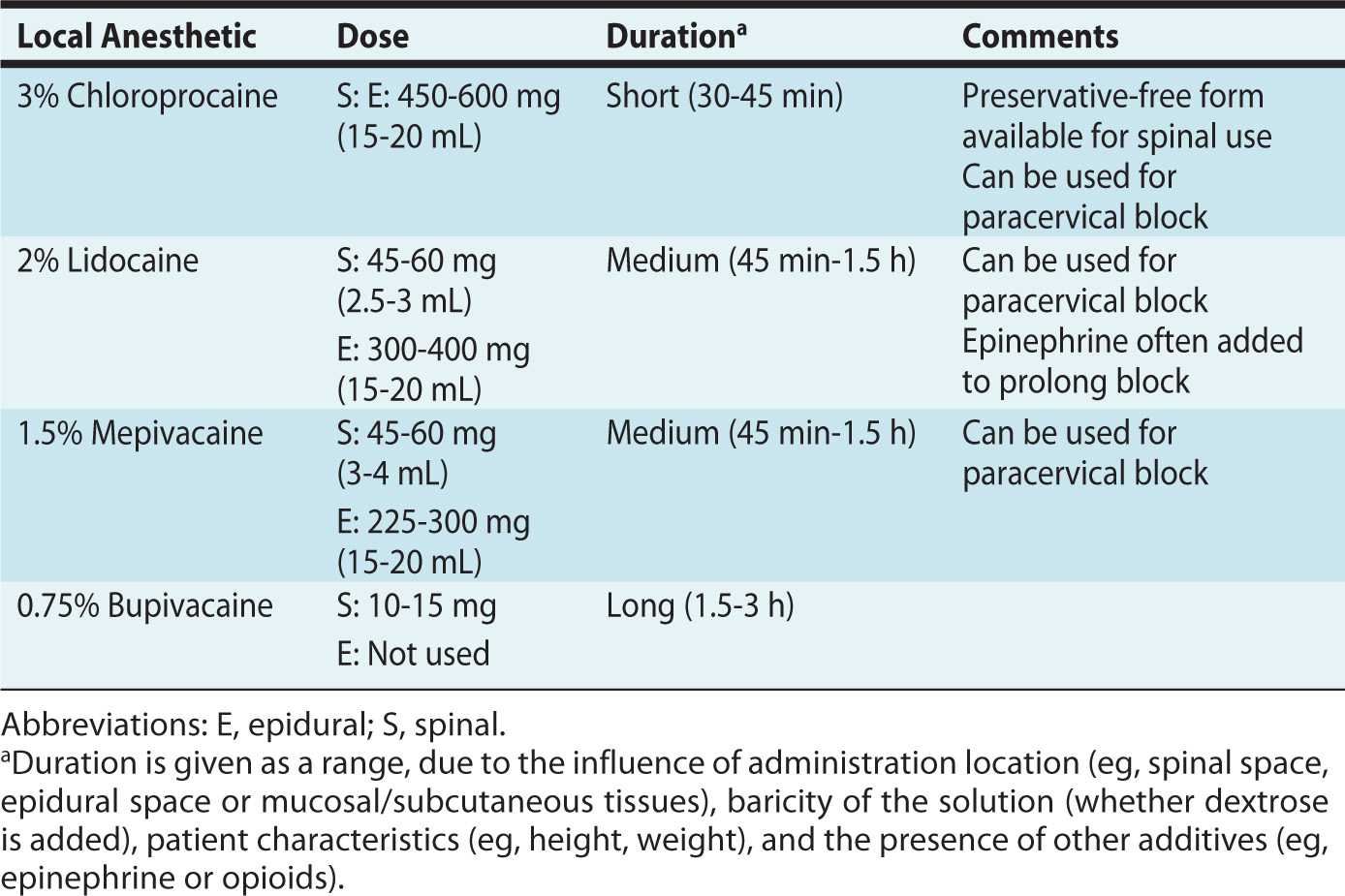

The presence of a functioning labor epidural catheter allows for the provision of an anesthetic for immediate PPTL. A sensory level of at least T5-T6 is needed to block visceral pain during exposure and manipulation of the fallopian tubes. Most commonly, 2% lidocaine with epinephrine with fentanyl 100 μg is used; 3% 2-chloroprocaine, a local anesthetic of shorter duration, may be used as well (Table 13-1). Some epidural catheters that have provided adequate analgesia during labor may fail to provide adequate anesthesia for PPTL, particularly if the interval since delivery is longer.4 One observational study demonstrated a significant decline in epidural catheter “reactivation” success when the postdelivery interval was greater than 24 hours,10 and another study observed highest success rates when the interval was less than 4 hours.11 As a consequence, if the procedure will most likely be delayed beyond 24 hours, an elective spinal anesthetic technique may be a better option. The functioning of the epidural catheter should be carefully evaluated prior to reactivation; in cases of unilateral or incomplete block or inadequate pain relief during labor analgesia, any plan to use the existing epidural catheter should be abandoned.

Table 13-1. Local Anesthetic Agents

Failure of epidural catheter reactivation may result in complications, including high or total spinal anesthesia if a spinal technique is performed shortly after epidural administration of large volumes (> 10 mL) of local anesthetics. PPTL is an elective procedure; therefore, in situations where the epidural anesthesia produced is suboptimal, it may be better to allow any block to recede before attempting spinal anesthesia.

SPINAL ANESTHESIA

In patients who do not have a functioning epidural catheter, spinal anesthesia can be performed. Some anesthesiologists prefer spinal anesthesia, regardless of whether an epidural catheter is in place. Spinal anestheisa for postpartum tubal ligation has been shown to be associated with a reduction in overal operating room time and charges compared with attempted reactivation of an epidural catheter placed during labor.12 This should be weighed against the small but increased probability of headache after dural puncture.

Some studies suggest that patients undergoing PPTL require more spinal bupivacaine compared to patients undergoing cesarean delivery, to achieve the same level and duration of anesthesia.13–14 Pregnancy is associated with an enhanced spread and sensitivity to local anesthetics. This alteration in sensitivity has been attributed to decreased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume secondary to vertebral venous plexus engorgement and increased intra-abdominal pressure,15,16 as well as enhanced neural susceptibility to local anesthetics, which may be related to high progesterone levels.17,18 Dose requirements return to nonpregnant levels within 24 to 48 hours’ postpartum,13 which may be related to an increase in CSF volume following relief of vena caval compression or due to the rapid decrease in progesterone levels following delivery. Nevertheless, given the short nature of the procedure, low doses of local anesthetics have been reported to be adequate for postpartum sterilization. A dose-finding study for hyperbaric bupivacaine found that 7.5 mg provided adequate anesthesia for PPTL, lasting approximately 60 minutes. The time of onset to peak sensory level in this study was approximately 20 minutes. Although larger doses can be associated with prolonged motor block and recovery times,19 a dose of 12 mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine has been shown to be effective and safe in providing surgical anesthesia for PPTL.14 To avoid general anesthesia in case of a failed single-shot spinal, a dose greater than 10 mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine has been suggested for routine use.14

GENERAL ANESTHESIA

General anesthesia is frequently avoided, particularly when the tubal ligation is performed in the immediate postpartum period, when the effects of pregnancy are still present with regard to slowing of gastric emptying6–9 and decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone. Should general anesthesia be selected, particularly during the immediate postpartum period, such procedures should be used as an opportunity to apply “obstetric” airway management techniques, including a rapid sequence induction, use of a videolaryngoscopy intubation device, and greater attention during extubation and recovery.20

Similar to local anesthetics, volatile agents may have decreased minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) values during pregnancy, which also has been attributed to increased progesterone concentration. MAC values usually return to normal 12 to 24 hours after delivery.21 Uterine atony may occur in the immediate postpartum period, and as a consequence, volatile agents should be maintained at levels that will not reduce the uterine response to oxytocin (0.5 MAC).22

Many patients undergoing surgery in the postpartum period are breastfeeding. Because most anesthetics are cleared rapidly, the quantity excreted is insignificant with minimal to no neonatal clinical effects.

CERVICAL CERCLAGE

Cervical cerclage, a surgical procedure to keep the cervical os closed during pregnancy with a purse-string type of stitch, is used for treatment of cervical incompetence. This is a condition characterized by painless cervical dilation with or without herniation and rupture of fetal membranes. These patients typically have a history of recurrent second trimester pregnancy loss. Cervical incompetence can be caused by congenital, anatomical, hormonal, or elastin/collagen abnormalities; alternatively, it is associated with a history of cervical trauma or surgery.

The absolute benefit of cervical cerclage to prevent preterm birth has been questioned; however, most patients with a diagnosis of cervical incompetence undergo cervical cerclage placement.23 An individual patient data meta-analysis found a nonsignificant trend toward reduction of pregnancy loss or neonatal death in patients with singleton pregnancies, whereas for the small number of multiple gestation pregnancies that were evaluated, a worsened outcome was observed.24

Obstetric Considerations

Cervical cerclage can be performed using either a transvaginal or transabdominal approach. The transabdominal approach is typically reserved for those patients in whom a transvaginal cerclage has failed or if no substantial cervical tissue is present.25 The most commonly performed transvaginal cerclage procedures are the McDonald cerclage and the modified Shirodkar cerclage. In both procedures, a circumferential suture is placed around the cervix at or near the level of the internal cervical os. With the McDonald cerclage, the cervical mucosa is left intact. With the Shirodkar cerclage, in contrast, the mucosa is incised anteriorly and posteriorly, and the ligature is placed submucosally.

COMPLICATIONS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree