TOPICS

2. Preoperative Assessment and Consent

5. Administration of Antibiotics

7. Administration of Surgical Anesthesia

8. Fluid Coloading: Prevention of Hypotension With Regional Anesthesia

10. Administration of Uterotonics

11. Postoperative Analgesia Planning

12. Complications of Anesthesia

INTRODUCTION

The increase in the cesarean delivery rate in the United States has reached near epidemic proportions. As of 2010, approximately 30% of all births in the United States occurred via cesarean delivery, and projections estimate a continued increase over time. Therefore, attention to the anesthetic management of these patients will continue to be of increasing importance.

The typical sequence of events for providing anesthesia for cesarean delivery is as follows:

1. Preoperative assessment and consent

2. Aspiration prophylaxis

3. Placement of monitors

4. Administration of antibiotics

5. Patient positioning

6. Administration of surgical anesthesia

7. Fluid coloading

8. Management of hypotension

9. Administration of uterotonics

10. Postoperative analgesia planning

Each of the components will be discussed in the following sections.

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT AND CONSENT

Assessment

Prior to initiation of anesthesia, a thorough preoperative assessment should be completed. In addition to regular components of the history in obstetric patients, specific attention should also be given to relevant obstetric issues such as medical conditions that may complicate surgery (ie, obesity, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes) and number of previous cesarean deliveries.1

Physical examination should include an examination of the back if neuraxial anesthesia is planned.1 An airway examination should be timed close to surgery because evidence has shown that there may be changes in the Mallampati classification of the airway with pregnancy/labor.2

Routine laboratory tests may not be necessary for all women prior to cesarean delivery. However, there is controversy among practicing anesthesiologists regarding whether a routine platelet count should be obtained prior to regional anesthesia. Certainly, in high-risk patients, such as parturients with severe preeclampsia, gestational thrombocytopenia, or history of coagulation disorders, a platelet count and/or coagulation studies may be necessary. A sample of the patient’s blood should be sent to the blood bank for all cesarean deliveries. The decision to type and screen or type and cross-match blood should be made based on the likelihood of requiring a blood transfusion.

Consent

During the consent process, the patient should be informed of the risks and benefits of the anesthetic planned for the procedure. Although there are many potential risks with neuraxial and general anesthesia, generally the most common risks should be discussed. For neuraxial anesthesia, these should include infection, bleeding, risk of postdural puncture headache, hypotension, and patchy/failed block requiring a repeat puncture or conversion to general anesthesia.

ASPIRATION PROPHYLAXIS

The estimated incidence of pulmonary aspiration in women undergoing cesarean delivery is 1 in 661 and appears to be decreasing. The decline is likely to be multifactorial, is related to the increased use of neuraxial anesthesia and decreased use of general anesthesia, adherence to fasting guidelines in obstetric practice, and routine use of antacid prophylaxis.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) recommends withholding clear liquids for 2 hours prior to elective cesarean delivery and withholding solids for 6 to 8 hours, depending on the fat content of the meal and the presence of comorbidities such as diabetes.1 For women who are in labor, it is controversial whether they should be allowed to eat light meals during labor. A Cochrane review evaluating oral intake in labor found no difference in labor or neonatal outcomes when low-risk patients were allowed liquid/solid intake3 and concluded that low-risk patients should be allowed to eat and drink. The difficulty with these studies is that aspiration is a relatively rare event, and the meta-analyses did not have sufficient statistical power to assess maternal aspiration as a primary outcome. Although active labor combined with or without neuraxial analgesia does slow gastric emptying, particularly especially with prior administration of opioids, most institutions do allow laboring women to drink clear liquids in labor but do not allow ingestion of solid food because of the perceived increased aspiration risk.

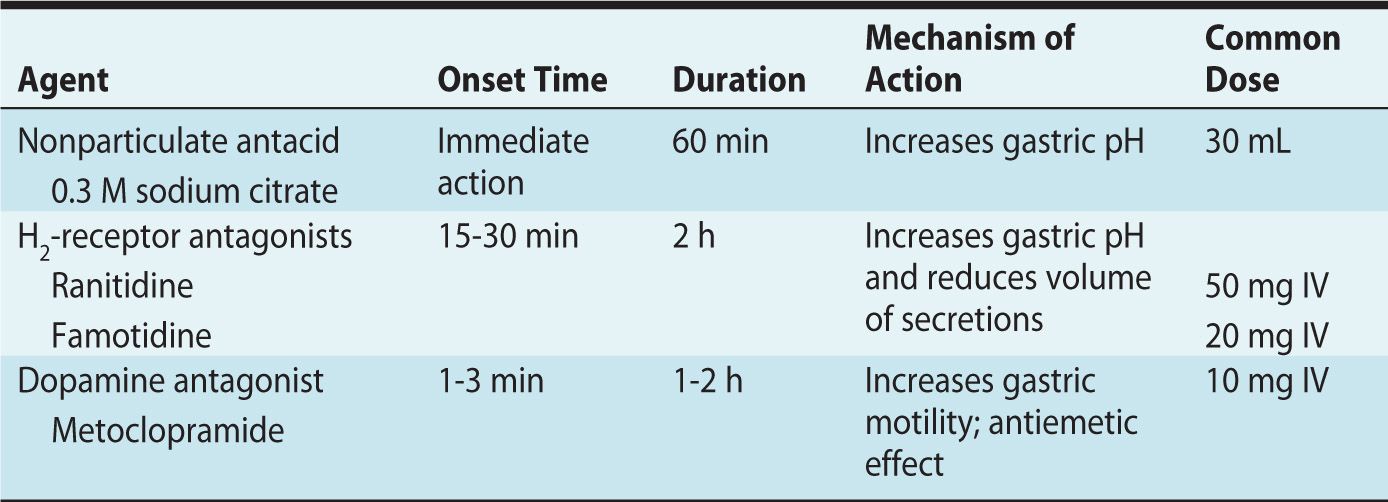

Prior to cesarean delivery, pharmacologic aspiration prophylaxis should be given. Three classes of drugs are routinely used: nonparticulate antacids, H2-receptor antagonists, and dopamine antagonists. Of the three, in an emergency, the most important to administer is the nonparticulate antacid as it has the fastest onset and decreases gastric acidity. Table 9-1 summarizes the onset, mechanism of action, and common doses of these agents.

Table 9-1. Commonly Used Aspiration Prophylaxis Medications

PLACEMENT OF MONITORS

As with all surgical procedures, ASA standard monitors are required. Whether or not the electrocardiogram (ECG) leads need to be on the patient during placement of neuraxial anesthesia is controversial. Temperature assessment is only required during cesarean deliveries under general anesthesia. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology states that fetal heart rate should be documented prior to surgery in all but the direst emergencies.

Invasive hemodynamic monitoring is not required for routine cesarean deliveries in healthy parturients, but should be considered on a case-by-case basis for high-risk deliveries or patients with cardiopulmonary disease.

ADMINISTRATION OF ANTIBIOTICS

The use of prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean delivery reduces maternal infectious morbidity. However, the timing of the antibiotic administration has been controversial. It was previously thought that administration of antibiotics prior to umbilical cord clamping would interfere with neonatal sepsis evaluation should it be necessary, as well as lead to antibiotic resistance in the newborn. However, several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that there is a decrease in endometritis and/or wound infection when antibiotics are administered prior to skin incision, as opposed to at umbilical cord clamping, with no increased adverse effects on the mother or fetus. Indeed, wound infection rates when antibiotics are held until cord clamp are equivalent to not having given antibiotics at all. Given this evidence, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recently issued a Committee Opinion in which they recommend that antibiotic prophylaxis be administered within 60 minutes of the start of a cesarean delivery.4 Exceptions to this include patients who have already received appropriate antibiotics (such as those being treated for chorioamnionitis) or those patients who are undergoing emergency cesarean deliveries. In the latter situation, antibiotics should be administered as soon as they are available. Considering that placement of regional anesthesia may be difficult in some parturients, we suggest that antibiotics be administered after induction of regional anesthesia during skin preparation; in this way, the interval between antibiotic administration and surgical incision will always be within 60 minutes.

PATIENT POSITIONING

Prior to delivery of the infant, the patient should be placed in left uterine displacement. A minimum of 15-degree leftward tilt prevents aortocaval compression syndrome, which results from the gravid uterus resting on the aorta and vena cava. This in turn leads to reduced venous return to the heart. After delivery of the infant, the left tilt may be removed.

ADMINISTRATION OF SURGICAL ANESTHESIA

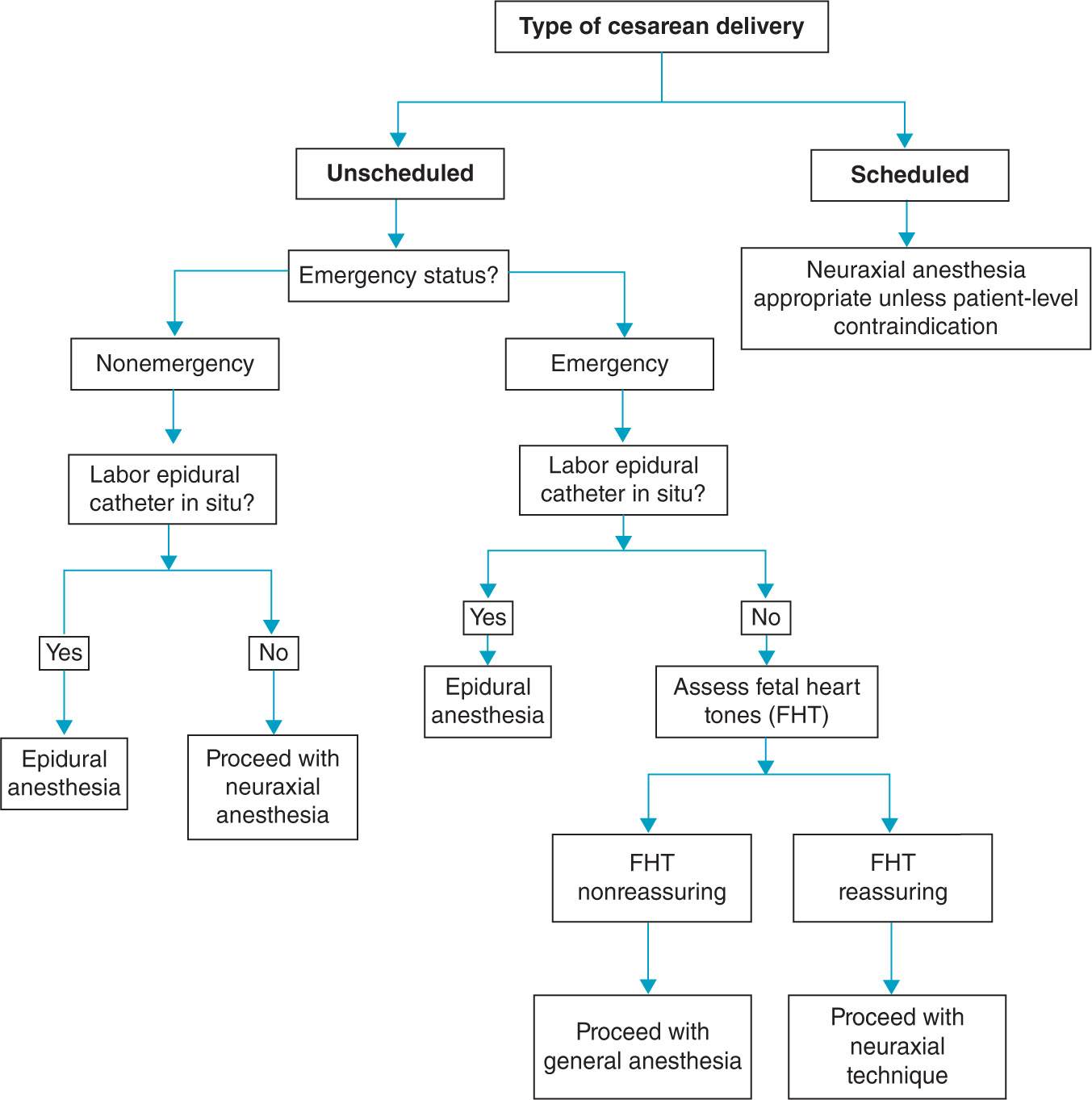

The type of anesthesia selected for cesarean delivery needs to be tailored to the individual woman’s situation. The anesthetic plan is usually determined by the urgency of the cesarean delivery and maternal/fetal condition. There are three types of anesthesia for cesarean delivery: (1) general anesthesia; (2) neuraxial anesthesia, which includes (a) spinal anesthesia, (b) epidural anesthesia, (c) combined spinal-epidural anesthesia, and (d) continuous spinal anesthesia; and (3) Infiltration of local anesthesia, which is rarely used. The flow chart in Figure 9-1 describes an approach to deciding on an initial anesthetic plan for a cesarean delivery.

Figure 9-1. Proposed algorithm to guide anesthetic decision-making.

General Anesthesia

General anesthesia may be required in dire emergency situations where there is immediate threat to the mother or infant, when there is insufficient time to initiate neuraxial anesthesia, or in women who have contraindications to neuraxial anesthesia. Other reasons for the use of general anesthesia include hypovolemia (due to maternal hemorrhage) and infection. Due to the physiologic changes of pregnancy, all patients undergoing general anesthesia are considered to be at risk for aspiration; therefore, in addition to aspiration prophylaxis, rapid sequence intubation with cricoid pressure should be performed. The advantage of general anesthesia is that it allows the shortest “decision-to-incision” interval when compared to a de novo neuraxial technique. The trade-offs are a lower initial 1-minute Apgar score and an increased likelihood of uterine atony and bleeding related to the effects of halogenated agents.5

The following is a common approach to general anesthesia.6 Induction should occur after denitrogenation, skin decontamination, and confirmation that the surgical team is prepared to proceed with surgery in order to shorten the induction-to-delivery interval and reduce the potential for neonatal depression. After induction and intubation, the surgical team should be told to commence, and the patient should be ventilated with 100% oxygen and up to 1 minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) of a potent inhalational agent. Following delivery of the infant, the FiO2 may be decreased to 30% and 70% nitrous oxide added, while maintaining a one-half MAC of inhalational agent. At this point, benzodiazepines and opioids may be administered. The stomach should be decompressed with an orogastric tube, and the temperature should be monitored. For most surgeries, it is not necessary to administer additional muscle relaxant beyond the intubating dose. Because the risk of hemorrhage is increased with general anesthesia,7 it may be prudent to increase the dose of oxytocin administered after delivery. Patients should be extubated awake and monitored in a postanesthesia recovery unit. It is critical that postanesthesia care units have systems and resources in place identical to those of main operating rooms. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that anesthesia-related deaths due to airway obstruction or hypoventilation occurred during emergence and recovery, not during the conduct of general anesthesia.8

Neuraxial Anesthesia

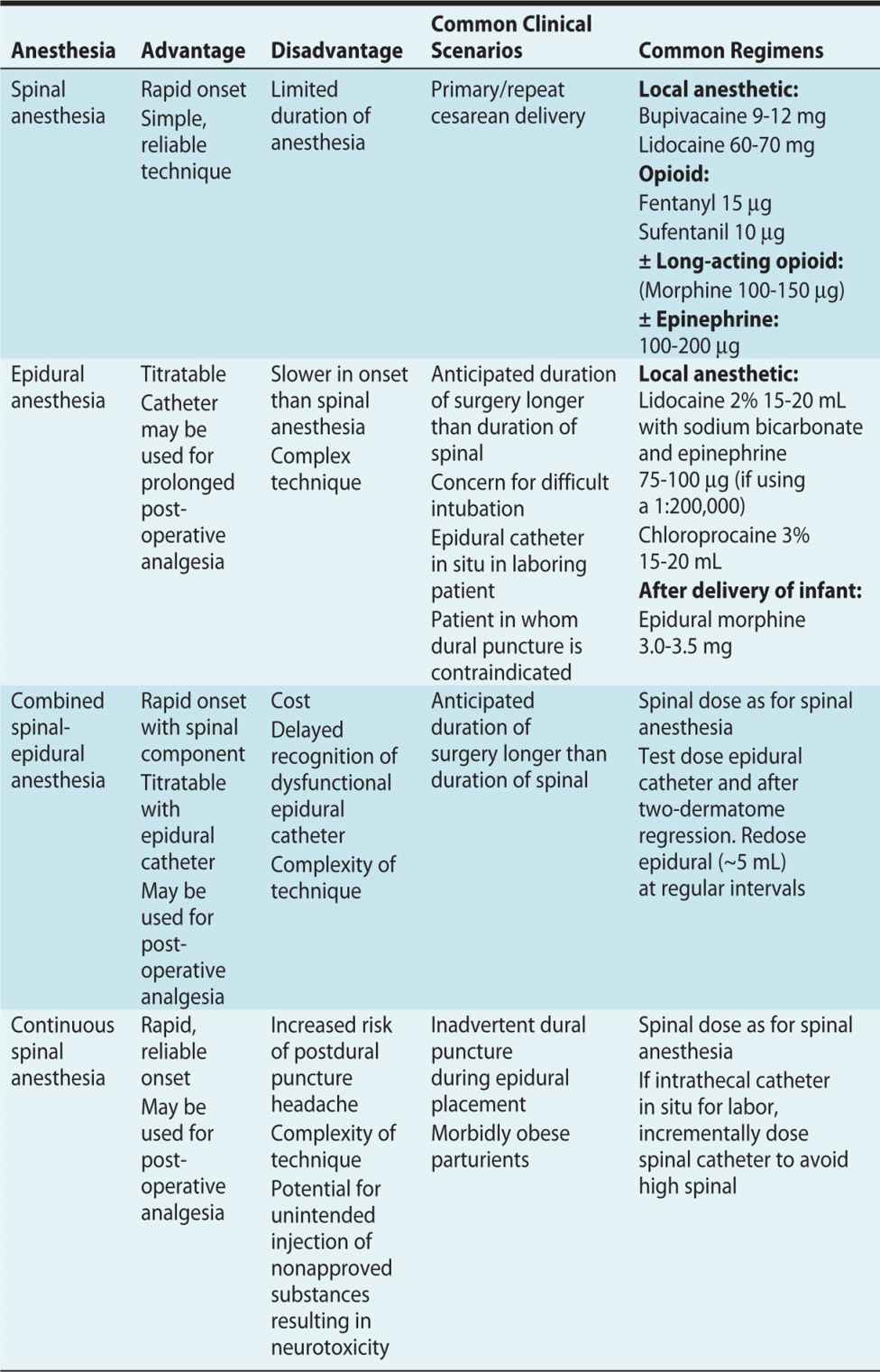

The overwhelming majority of cesarean deliveries are performed using neuraxial anesthesia, with the most common anesthetic being a single-shot spinal. Table 9-2 describes the advantages, disadvantages, common scenarios, and common dosing strategies for each neuraxial anesthetic regimen.

Table 9-2. Neuraxial Anesthesia Options

With all neuraxial techniques, a T4-T6 dermatomal level should be established prior to commencement of the surgery; otherwise the patient may experience breakthrough pain and require supplemental opioids or conversion to general anesthesia. The assessment of sensory level should be to touch/pinprick because the discrepancy between cold and touch may exceed two dermatomes.9

Common dosing regimens for spinal anesthesia include a local anesthetic agent with a short-acting opioid. The addition of an opioid allows for a reduction in local anesthetic dose, thus decreasing the incidence of hypotension and other local anesthetic-related side effects. For women without clinical contraindications, morphine is often added for extended postoperative analgesia. For patients in whom the duration of surgery is anticipated to exceed the usual duration of the spinal, anesthetic epinephrine may be added to the spinal to enhance anesthesia, or alternatively, an epidural or combined spinal-epidural technique may be chosen.

In some instances, epidural anesthesia may be chosen for cesarean delivery. However, the most likely scenario for epidural use is that there is a well-functioning epidural catheter at the time the decision to deliver via cesarean delivery is made in a laboring woman, and the block reinforced accordingly. The patient may not require as much epidural local anesthetic as a patient who is receiving de novo epidural anesthesia.

EPIDURAL ANESTHESIA IN WOMEN WITH IN-DWELLING LABOR EPIDURAL CATHETERS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree