TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

The word anaphylaxis (ana: backward; phylaxis: guard, or “against protection”) was coined by Paul Portier and Charles Richet, two scientists who unexpectedly induced acute anaphylaxis in their experimental dogs during an attempt to produce vaccines for prophylaxis against a toxin (actinotoxin) from a sea anemone, Actinia sulcata.1 Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening, systemic event caused by immediate hypersensitivity reaction. Although it is relatively infrequent during pregnancy, the potentially fatal effects on the mother and the unborn baby warrant prompt recognition and immediate management. Severe anaphylaxis, in general, affects 1 to 3 per 10,000 population,2 but the incidence during anesthesia is reported to range from as high as 1 in 4000 to 1 in 25,000.3 The prevalence of anaphylaxis in pregnant patients is approximately 3 per 100,000 deliveries.4

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anaphylaxis is a systemic form of immediate hypersensitivity reaction caused by immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated release of mediators from mast cells and basophils. Exposure to allergen in a susceptible individual initiates a cascade of events, including activation of helper T-2 cells (TH2 cells) and stimulation of IgE-secreting B cells. IgE then binds to FcεRI receptors on mast cells and basophils. After several episodes of exposure to the inciting allergen, a cross-linkage develops between the receptors by the allergen that triggers the mast cells to release mediators, including histamine, tryptase, tumor necrosis factor, and so on. These mediators then produce the serious manifestations of anaphylactic reaction in various organ systems such as the respiratory system (stridor, bronchospasm, hypoxia), cardiovascular system (hypotension, tachycardia, dysrhythmia), cutaneous system (erythema, pruritus, urticaria, angioedema), and gastrointestinal system (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea).5

Pregnant patients are thought to be predisposed to anaphylaxis as a result of alteration in cellular immunity, possibly due to increased level of progesterone.6 Also, increased production of TH2-type cytokine (which initiates the immediate hypersensitivity reaction) by maternal T cells at the fetomaternal interface and simultaneous inhibition of cytokine production from TH1 cells (which normally play a role in allograft rejection) during pregnancy help to maintain the pregnancy and to prevent fetal loss.7,8

CAUSATIVE AGENTS

During anesthesia, neuromuscular blocking agents (succinylcholine, rocuronium), latex (gloves, tourniquet), and antibiotics (penicillins and other cephalosporins) are implicated as the most common agents in the etiology of anaphylactic reactions. Other less frequently involved agents include colloids, propofol, chlorhexidine, iodinated contrast media, local anesthetics, and so on.9,10

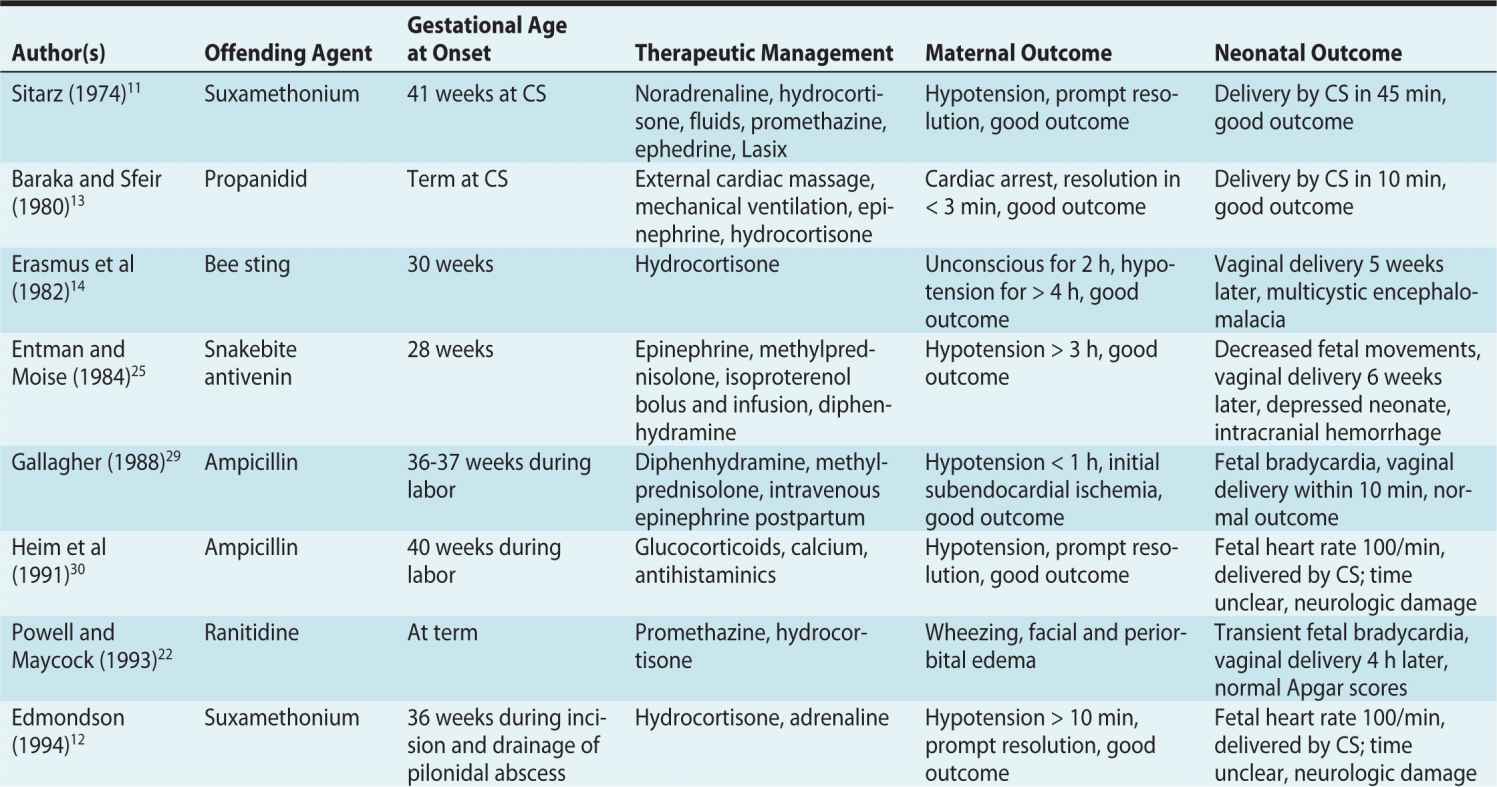

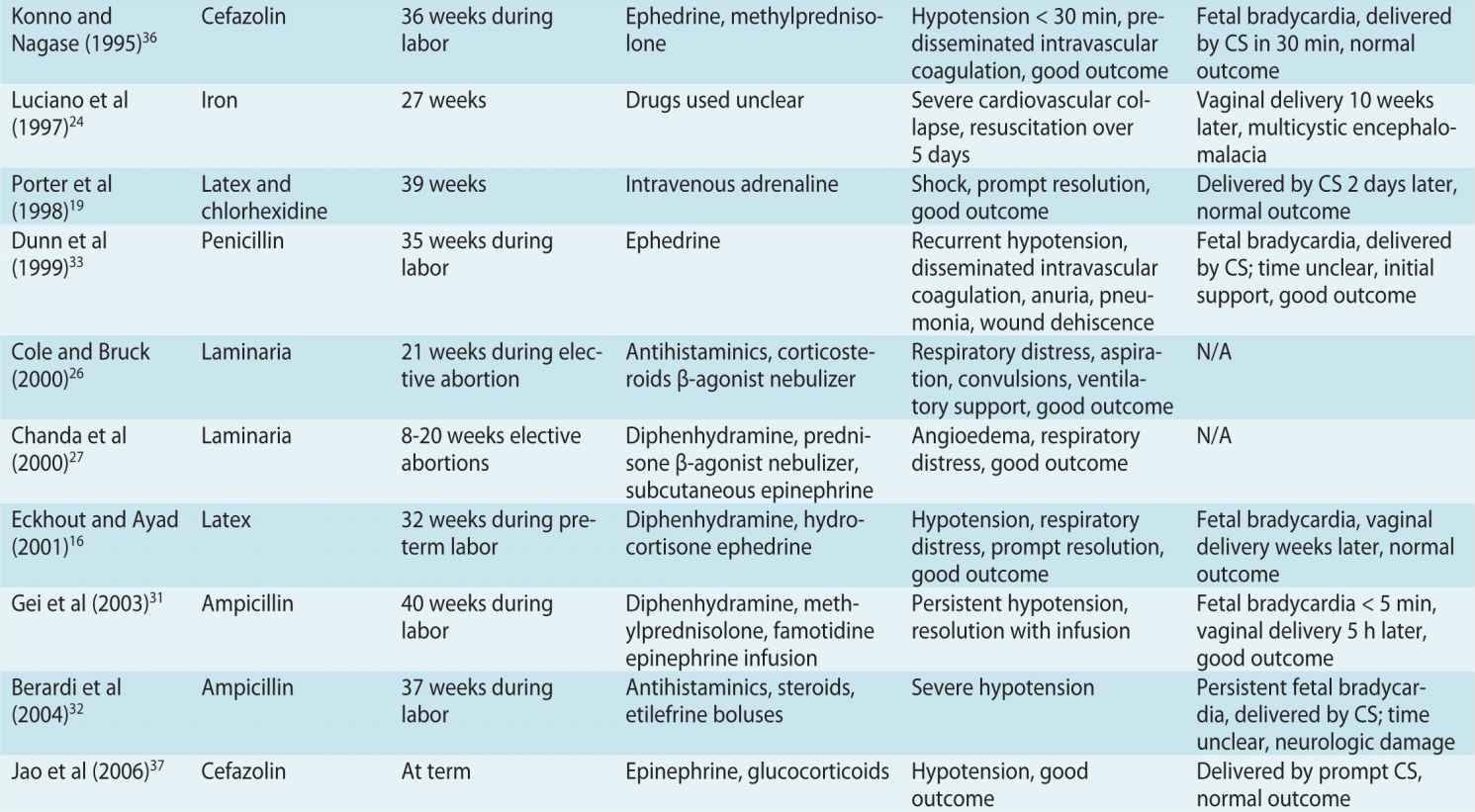

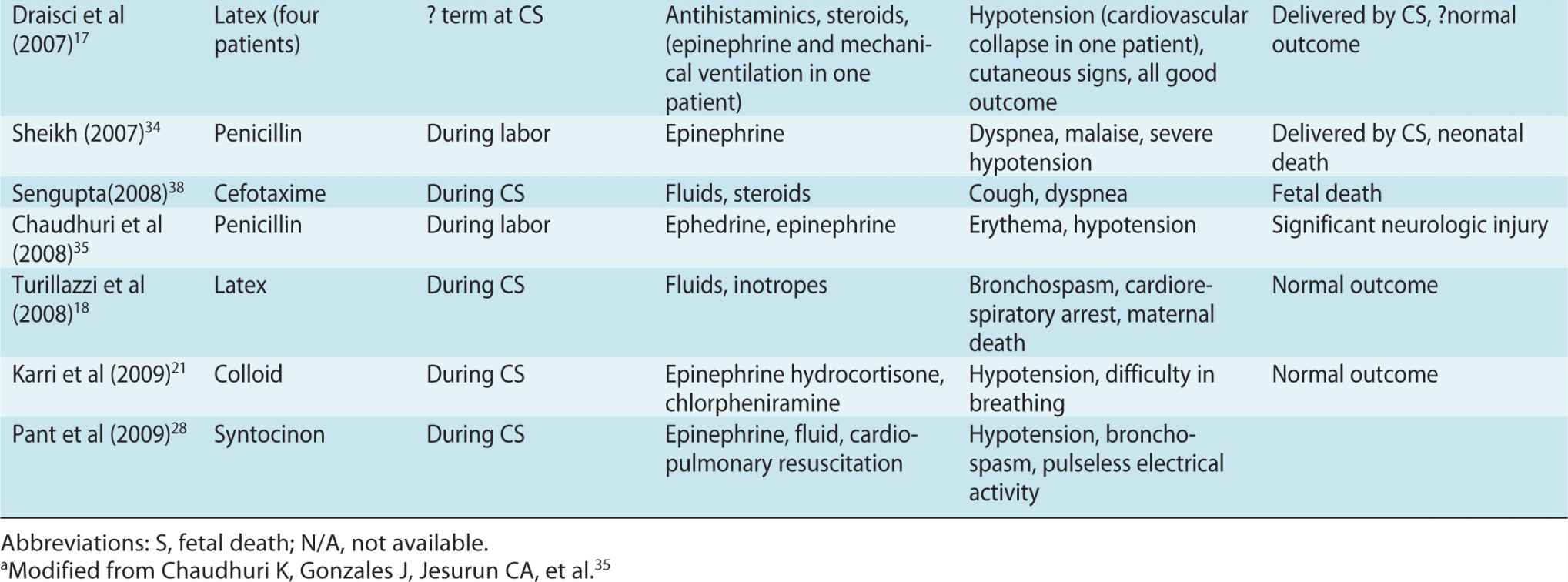

In one of the earliest reports, succinylcholine was implicated to be a causative agent for anaphylaxis in pregnant women.11 Several other agents have since been implicated in obstetric patients, including muscle relaxants,12 anesthetic induction agents,13 bee stings,14 latex,15–18 latex and chlorhexidine,19 synthetic colloid solutions,20,21 ranitidine,22,23 iron,24 antivenin after snakebite,25 laminaria (a hygroscopic cervical dilator prepared from seaweed),26,27 and synthetic oxytocin.28 However, one of the commonly reported agents to cause anaphylaxis are parenteral antibiotics including ampicillin,29–32 penicillin,33–35 and cephalosporins.36–38 One epidemiologic study found that the β-lactam antibiotics were the most common causative agents of anaphylaxis during pregnancy.4 Significant neurologic sequelae have been reported, especially with ampicillin.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

During anesthesia, a wide variety of clinical manifestations may commonly affect the cardiac (hypotension, bradycardia, asystole), cutaneous (urticaria, erythema), and respiratory (bronchospasm, difficulty to ventilate) systems. Anaphylaxis might also present with cardiovascular collapse, bronchospasm, or cutaneous symptoms.39 Cutaneous manifestations may be absent or may be missed during anesthesia because patients are covered by surgical drapes. In the majority of cases during anesthesia, anaphylaxis occurs immediately after parenteral injection of the offending agent.10

Clinical signs of anaphylaxis are categorized into four grades9,40:

• Grade 1: involvement of skin and mucosa only (generalized erythema, urticarial, angioedema)

• Grade 2: moderate multiorgan system involvement (cardiovascular: hypotension, tachycardia; respiratory: bronchospasm; difficulty to ventilate; gastrointestinal: nausea)

• Grade 3: severe life-threatening symptoms (cardiac collapse, bradycardia, dysrhythmia, bronchospasm)

• Grade 4: cardiac and/or respiratory arrest

Selected published case reports involving anaphylaxis during pregnancy are detailed in Table 17-1. Cardiac manifestations, especially maternal hypotension, are the most common clinical manifestation during anaphylaxis among pregnant patients.

Table 17-1. Clinical Manifestations of Anaphylaxis During Pregnancya

MANAGEMENT

Aggressive management of anaphylactic reaction immediately after suspicion is imperative to reduce morbidity and mortality of the mother and the unborn baby. The goals of management should be to inhibit the release of mediators and to modulate their actions. Peripheral vasodilation and capillary leakage, compounded by decreased venous return as a result of aortocaval compression from a gravid uterus, are important reasons for hypotension. Because fetal perfusion is directly proportional to uterine blood flow, maternal hypotension may cause ischemic damage to the vulnerable central nervous system of the baby infant. The magnitude and duration of the hypotension probably determine the extent of this injury.

Primary Management

Primary management9,41–43 includes a quick evaluation of airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC); cessation of all possible offending agents; informing the obstetrician (or surgeon); maintaining the airway with 100% oxygen; left uterine displacement; administering epinephrine; aggressive fluid resuscitation (rapid infusion of 1 to 2 L of crystalloid solution); and consideration for emergency cesarean section, if warranted.

Epinephrine is the cornerstone in the primary management of anaphylaxis. It should be started early in titrated doses. Failure to administer epinephrine expeditiously, or administering it in inadequate doses, is a frequent reason for poor outcome during anaphylaxis.10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree