Ambulatory Anesthesia

Ambulatory surgery is popular both for patients and those who own the facility (Lichtor JL. Ambulatory anesthesia. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan MK, Ortega R, Stock MC, eds. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013:XX–XX).

I. Place, Procedures, and Patient Selection

Ambulatory surgery occurs in a variety of settings (hospitals, freestanding satellite facilities, physician’s offices).

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services generally pays ambulatory centers 65% of what hospital outpatient surgical facilities receive.

Procedures appropriate for ambulatory surgery are those associated with postoperative care that is easily managed at home and with low rates of complications that require intensive physician or nursing management

Scoring systems have been developed to help determine the likelihood of hospital admission after ambulatory surgery (older than 65 years, operating times longer than 120 minutes, cardiac diagnoses, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, regional vs. general anesthesia).

Many facilities set a 4-hour limit as a criterion for performing a procedure.

The need for a transfusion is not a contraindication for ambulatory procedures. Some patients undergoing liposuction as outpatients are given autologous blood.

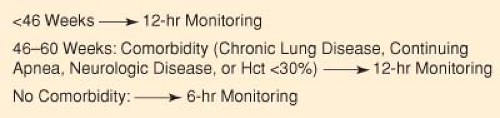

Infants whose postconceptual age is <46 weeks or whose actual age is <60 weeks should be monitored for 12 hours after the procedure because they are at risk of developing apnea even without a history of apnea. Infants older than 46 weeks and younger than 60 weeks without disease should be monitored for 6 hours after the procedure (Fig. 30-1).

Advanced age alone is not a reason to disallow surgery in an ambulatory setting. Age, however, does affect the pharmacokinetics of drugs. Even short-acting drugs such

as midazolam and propofol have decreased clearance in older individuals.

Hospital admission by itself is not necessarily bad if it results in a better quality of care or uncovers the need for more extensive surgery.

Obese patients are not more likely to have adverse outcomes, but they have a higher incidence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has published practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with OSA.

Patients who undergo ambulatory surgery should have someone to take them home and stay with them afterward to provide care.

After the patient has returned home, he or she must be able to tolerate the pain from the procedure, assuming adequate pain therapy is provided.

Patients undergoing certain procedures, such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy or transurethral resection of the prostate, should live close to the ambulatory facility because postoperative complications may require their prompt return.

II. preoperative Evaluation and Reduction of Patient Anxiety

Each outpatient facility should develop its own method of preoperative screening to be conducted before the day of surgery (history, medications, previous anesthetics, transportation and child care needs, dietary restrictions, attire, arrival times, laboratory tests). The preoperative screening is the ideal time for the anesthesiologist to talk with the patient. Automated history taking may also prove beneficial during patient screening.

Upper Respiratory Tract Infection (Table 30-1)

Airflow obstruction has been shown to persist for up to 6 weeks after viral respiratory infections in adults. For

this reason, surgery should be delayed if an adult presents with an upper respiratory infection (URI) until 6 weeks have elapsed.

In the case of children, whether surgery should be delayed for this length of time is questionable. URI seems to be associated with an increased risk of perioperative respiratory events only when symptoms are present or had been present within 2 weeks before the procedure.

Although surgery may be canceled because a child is symptomatic, the child may develop another URI when the procedure is rescheduled.

Generally, if a patient with a URI has a normal appetite, does not have a fever or an elevated respiratory rate, and does not appear toxic, it is probably safe to proceed with the planned procedure.

Restriction of Food and Liquids Prior to Ambulatory Surgery

To decrease the risk of aspiration of gastric contents, patients are routinely asked not to eat or drink anything for at least 6 to 8 hours before surgery.

Prolonged fasting can be detrimental to patients. Infants who fast longer have greater decreases in intraoperative blood pressure.

No trial has shown that a shortened fluid fast increases the risk of aspiration. Gastric volumes are actually lower when patients are allowed to drink some fluids before surgery.

ASA practice guidelines for preoperative fasting allow a patient to have a light meal up to 6 hours before an elective procedure and support a fasting period for clear

liquids of 2 hours for all patients (including taking chronic medications) (Table 30-2). Coffee and tea are considered clear liquids.

Coffee and tea drinkers should follow fasting guidelines but should be encouraged to drink coffee before the procedure because physical signs of caffeine withdrawal (headache) can easily occur.

It is unclear whether rehydration during surgery is equivalent to a shorter fast before surgery in relation to postoperative nausea and vomiting.

ASA practice guidelines do not recommend “routine use” of gastrointestinal stimulants (metoclopramide), gastric acid secretion blockers (histamine-2 receptor antagonists), antacids, antiemetics, or anticholinergics.

Anxiety Reduction

Preoperative reassurance from nonanesthesia staff and the use of booklets reduce preoperative anxiety. However, the use of booklets is less effective than a preoperative visit by the anesthesiologist. Audiovisual instructions also reduce preoperative anxiety.

Much of a child’s anxiety before surgery concerns separation from the parent or parents. If the parents are calm and can effectively manage the physical transfer to a friendly and playful anesthesiologist or nurse, premedication may not be necessary.

Family-centered care (videotapes, pamphlets, mask practice kits) has become popular and is useful for decreasing children’s preoperative anxiety.

Table 30-1 Independent Risk Factors for Adverse Respiratory Events in Children with Upper Respiratory Tract Infections | |

|---|---|

|

Table 30-2 Suggested Guidelines to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|