Anesthesia for Vascular Surgery

Anesthesiologists may have greater influence in reducing the morbidity and costs of vascular surgery than in any other surgical procedure (Smaka TJ, Miller TE, Hutchens MP, Schenning K, Fleisher LA, Gan TJ, Lubarsky DAL. Anesthesia for vascular surgery. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan MK, Ortega R, Stock MC, eds. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013:1112–1143).

I. Vascular Disease: Epidemioplogic Medical and Surgical Aspects

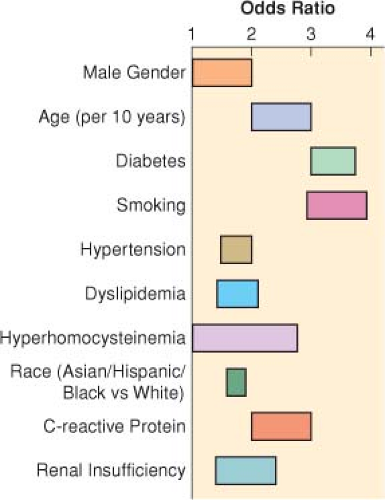

Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is a generalized inflammatory disorder of the arterial tree with associated endothelial dysfunction. The commonly accepted causes of atherosclerosis are endothelial damage (injury) caused by hemodynamic shear stress, inflammation from chronic infections, hypercoagulability resulting in thrombosis, and the destructive effects of oxidized low-density lipoproteins (Table 39-1).

Natural History of Patients with Peripheral Vascular Disease (Fig. 39-1)

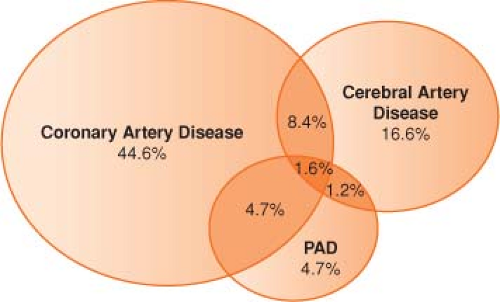

Atherosclerosis must be recognized as a systemic disease with important sequelae in many other regional circulations (coronary atherosclerosis, stroke, abdominal aortic aneurysm [AAA], peripheral arterial disease) (Fig. 39-2).

Noninvasive angiography (magnetic resonance angiography and computed tomographic angiography) enable excellent noninvasive definition of the vascular anatomy.

AAAs occur in up to 5% of men older than 65 years of age. (The risk of rupture is very low for aneurysms ≤4 cm in diameter but rises exponentially for aneurysms >5 cm.)

Medical Therapy for Atherosclerosis

Continuation of chronic medical therapy, including use of antihypertensives such as β-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, statin drugs,

aspirin, and control of hyperglycemia with hypoglycemics or insulin, may reduce perioperative morbidity and mortality in vascular surgery.

ACE inhibitors have numerous beneficial effects in patients with arteriosclerotic vascular disease, including plaque stabilization. Cessation of smoking may be the most effective “medical” therapy.

Table 39-1 Clinical Predictors of Increased Periopeartive Risk for Myocardial Infarction, Congestive Heart Failure, and Death | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

II. Chronic Medical Problems and Management in Vascular Surgery Patients

Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Peripheral Vascular Disease. The presence of uncorrected coronary artery disease appears to double the 5-year mortality rate after vascular surgery.

Percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) directed at reducing perioperative cardiac events do not appear to reduce perioperative myocardial infarction (MI);

however, PCI performed in the distant past may be protective after vascular surgery.

In the first 6 weeks after coronary stent placement, noncardiac surgery carries considerable risks. There are two basic types of stents: bare metal stents and drug-eluting stents. Although drug-eluting stents have a reduced incidence of restenosis, they are slow to endothelialize, and the exposed stent material remains thrombogenic far longer than bare metal stents. Therefore, the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 325 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day) differs: 1 month for bare-metal stents, 12 months or more for drug-eluting stents.

Guidelines suggest continuing aspirin therapy in all patients with a coronary stent and discontinuing clopidogrel for as short a time interval as possible for patients with bare-metal stents for an <30 days or drug-eluting stents for <1 year.

Two distinct types of perioperative MI (PMI)—“early” and “delayed”—occurring after vascular surgery have been identified.

Early PMI resembles that of acute nonsurgical MI and is probably attributable to acute coronary occlusion resulting from plaque rupture and thrombosis.

The “delayed PMI” is associated with sustained elevation of heart rate, absence of chest pain, and prolonged premonitory episodes of ST segment depression before overt MI. The delayed PMI resembles that resulting from increase in oxygen demand in the setting of fixed coronary stenosis.

Guidelines from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology classify the clinical predictors of increased perioperative cardiovascular risk (MI, congestive heart failure, and death) as “major,” “intermediate,” and “minor.” (Table 39-2).

Preoperative Coronary Revascularization. Myocardial revascularization may have long-term benefits in patients with triple-vessel coronary disease or poor left ventricular function. However, mortality rates associated with these techniques are consistently higher in patients with peripheral vascular disease compared with those without. Whether preoperative coronary revascularization actually protects against perioperative cardiac events is controversial.

Table 39-2 Pharmacologic Prophyaxis Agains Acute Vascular Events in Patients Undergoing Vascular Surgery | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

III. Other Medical Problems in Vascular Surgery (Table 39-3)

Table 39-3 Other Medical Problems in Vascular Surgery Patients | |

|---|---|

|

IV. Organ Protection in Vascular Surgery Patients

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree