Acute Pain Management

Appropriate management of patients with acute perioperative pain using multimodal or balanced analgesia is crucial (Macres SM, Moore PG, Fishman SM. Acute pain management. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan MK, Ortega R, Stock MC, eds. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013:1611–1644). Inadequate relief of postoperative pain has adverse physiologic effects that may contribute to significant morbidity and mortality, resulting in the delay of patient recovery and return to daily activities.

I. Acute Pain Defined

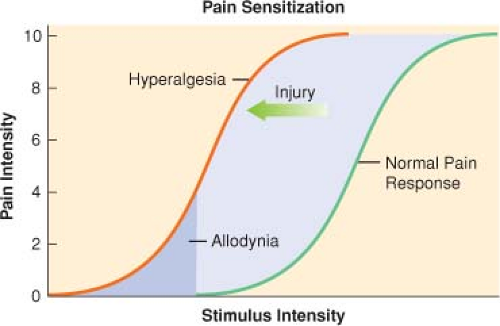

Acute pain has been defined as the normal, predicted, physiological response to an adverse chemical, thermal, or mechanical stimulus. Generally, acute pain resolves within 1 month. Acute pain-induced change in the central nervous system is known as neuronal plasticity. This can result in sensitization of the nervous system, resulting in allodynia and hyperalgesia.

II. Anatomy of Acute Pain

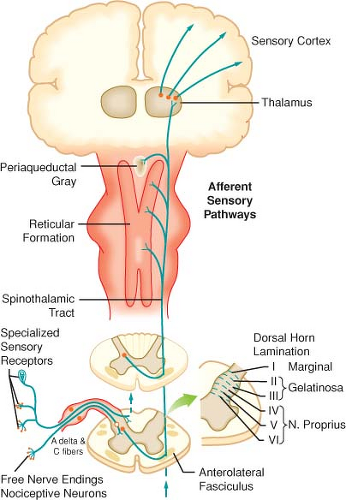

(Figs. 56-1 and 56-2 and Table 56-1). α-δ Fibers transmit “first pain,” which is described as sharp or stinging in nature and is well localized. Polymodal C fibers transmit “second pain,” which is more diffuse in nature and is associated with the affective and motivational aspects of pain.

III. Pain Processing

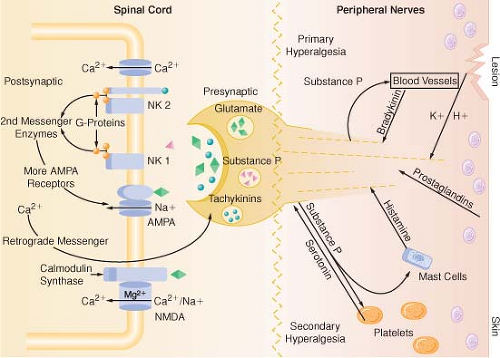

Tissue injury tends to fuel neuroplastic changes within the nervous system, which results in both peripheral and central sensitization. Clinically, this can manifest as hyperalgesia (exaggerated pain response to a normally painful stimulus) or allodynia (painful response to a typically nonpainful stimulus) (Fig. 56-3).

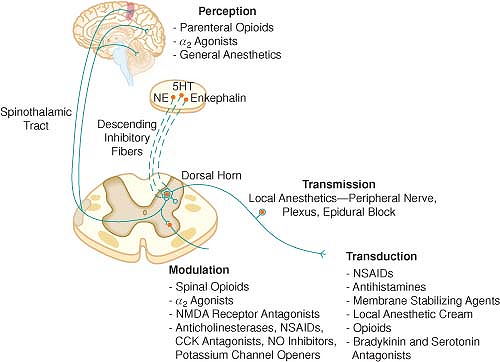

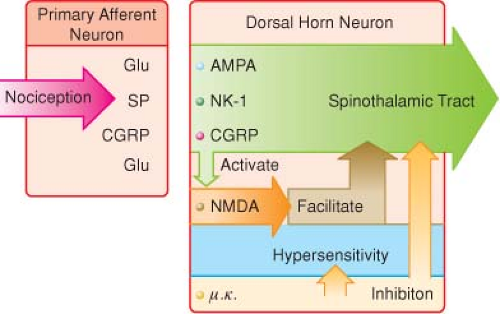

The four elements of pain processing are transduction, transmission, modulation, and perception (Fig. 56-4).

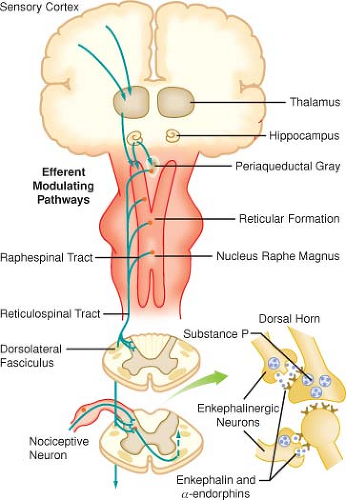

Modulation of pain transmission involves altering afferent neural transmission along the pain pathway. The dorsal horn of the spinal cord is the most common site for modulation of the pain pathway, and modulation can involve either inhibition or augmentation of the pain signals. Examples of inhibitory spinal modulation

include release of inhibitory neurotransmitters (γ-aminobutyric acid, glycine) and activation of descending efferent neuronal pathways (release of norepinephrine, serotonin, and endorphins in the dorsal horn).

Spinal modulation that results in augmentation of pain pathways is a consequence of neuronal plasticity. The phenomenon of “wind-up” is an example of central plasticity that results from repetitive C-fiber stimulation of wide-dynamic range (WDR) neurons in the dorsal horn.

A multimodal approach to pain therapy should target all four elements of the pain processing pathway.

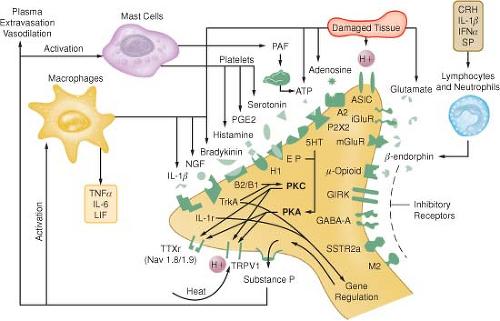

IV. Chemical Mediators of Transduction and Transmission

(Table 56-2 and Fig. 56-5)

Pain receptors include the NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate), AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-proprionic acid), kainite, and metabotropic receptors (Fig. 56-6).

Repetitive C-fiber stimulation of WDR neurons in the dorsal horn at intervals of 0.5 to 1.0 Hz may precipitate the occurrence of “wind-up” and central sensitization and secondary hyperalgesia (Fig. 56-7).

V. The Surgical Stress Response

Although similar, postoperative pain and the surgical stress response are not the same. Surgical stress causes release of cytokines and precipitates adverse neuroendocrine and sympathoadrenal responses

(increased secretion of the catabolic hormones [cortisol, glucagon, growth hormone, and catecholamines] and decreased secretion of the anabolic hormones [insulin and testosterone]) (Table 56-3).

(increased secretion of the catabolic hormones [cortisol, glucagon, growth hormone, and catecholamines] and decreased secretion of the anabolic hormones [insulin and testosterone]) (Table 56-3).

Table 56-1 Primary Afferent Nerves | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

VI. Preemptive Analgesia

The goal of preemptive analgesia is to prevent NMDA receptor activation in the dorsal horn, which causes “wind-up,” facilitation, central sensitization expansion of receptive fields, and long-term potentiation, all of which may lead to a chronic pain state.

VII. Strategies for Acute Pain Management

The majority of postoperative pain is nociceptive in character. Evidence suggests that women experience more pain after surgery than men and therefore require more morphine to achieve a similar level of pain relief.

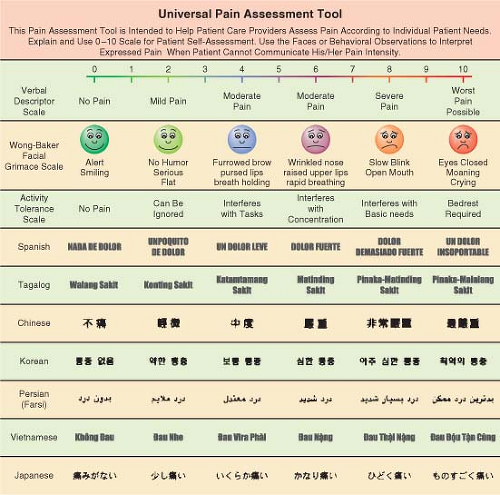

VIII. Assessment of Acute Pain

(Fig. 56-8). Common features of pain are usually reviewed during the assessment for acute pain (Table 56-4).

Table 56-2 Algogenic Substances | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IX. Opioid Analgesics

Opioid analgesics are the mainstay for the treatment of acute postoperative pain, and morphine is the “gold standard” (Table 56-5).

Hydromorphone is a semisynthetic opioid that has four to six times the potency of morphine, making it the ideal drug for long-term subcutaneous administration in opioid-tolerant patients.

Fentanyl is available for intravenous (IV), subcutaneous, transdermal, transmucosal, and neuraxial administration.

Figure 56-5. Schematic of the neurochemistry of somatosensory processing at peripheral sensory nervy endings.

Table 56-3 Consequences of Poorly Managed Acute Pain

System

Consequences

Cardiovascular

Tachycardia

Hypertension

Increase in cardiac work load

Pulmonary

Respiratory muscle spasm (splinting)

Decrease in vital capacity

Atelectasis

Hypoxia

Increased risk of pulmonary infection

Gastrointestinal

Postoperative ileus

Renal

Increased risk of oliguria and urinary retention

Coagulation

Increased risk of thromboemboli

Immunologic

Impaired immune function

Muscular

Muscle weakness and fatigue

Limited mobility with increased risk of thromboembolism

Psychological

Anxiety

Fear and frustration, resulting in poor patient satisfaction

Table 56-4 Features of Pain Commonly Addressed During Assessment

Onset of pain

Temporal pattern of pain

Site of pain

Radiation of pain

Intensity (severity) of pain

Exacerbating features (what makes the pain start or get worse?)

Relieving factors (what prevents the pain or makes it better?)

Response to analgesics (including attitudes and concerns about opioids)

Response to other interventions

Associated physical symptoms

Associated psychological symptoms

Interference with activities of daily living

Table 56-5 Opioid Equianalgesic Dosing

Drug

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access