Abdominal Pain

Diane M. Birnbaumer and Daniel P. Runde

Abdominal pain is simultaneously one of the most common and challenging chief complaints in emergency medicine. Abdominal pain accounts for 8% of the >120 million annual emergency department (ED) visits and is among the top 10 most common reasons people come to the ED (1). Its causes range from benign processes that present with severe pain to fatal processes that present with subtle findings. Despite improving imaging modalities, patients with abdominal pain continue to be diagnostically challenging. Even in patients who have undergone an appropriate workup, approximately 30% of patients will be discharged with the diagnosis of undifferentiated abdominal pain.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The importance of a thorough history and physical examination is absolutely paramount, as it helps narrow the vast differential diagnosis and focuses diagnostic testing. Failure to actually gather the relevant information (history and physical examination) is a more frequent cause of misdiagnosis than is misinterpretation of the data gathered.

When obtaining the history and performing a physical examination, it is important to understand that there are three major types of abdominal pain: visceral, somatic, and referred pain. They differ based on the anatomic pathway relaying the pain signal.

Visceral pain is relayed by afferent visceral fibers that are located in the walls of hollow organs and capsules of solid organs. These fibers are stimulated by stretching, distension, and excessive contraction. The visceral pain fibers originate from both sides of the spinal column, and enter the spinal column at multiple levels. This results in the perception of a poorly localized, midline pain that is described as dull or aching.

Somatic pain results from irritation of the parietal peritoneum. Pain is relayed by myelinated, unilateral afferent fibers that travel to a specific level in the spinal cord, making this pain more localized. It is usually described as sharp, intense, and well localized. Somatic pain is responsible for the physical findings of tenderness to palpation, guarding, and rebound.

Abdominal pain often begins as visceral pain and then progresses to somatic pain as the inflammation spreads to involve the parietal peritoneum. As an example, the early epigastric pain of gallbladder distension is characteristic of visceral pain whereas the right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain caused by local peritoneal inflammation with cholecystitis is deep somatic pain.

Referred pain is discomfort perceived at a site distant from the diseased organ. The diseased organ and the body area to which the pain is referred have overlapping transmission pathways at the level of the spinal cord. A common example of referred pain is shoulder pain caused by irritation of the diaphragm from free air or blood. In the same manner, extra-abdominal organs may cause referred pain to the abdomen, such as myocardial ischemia or pneumonia causing epigastric pain.

History

When evaluating the patient with abdominal pain, a thorough history of the abdominal pain is crucial. Specifically, the physician should determine the onset, time course, character, location, aggravating and alleviating factors, associated symptoms, and whether there are previous episodes of abdominal pain. The general medical and social history should also be obtained, including past medical and surgical history, medications, allergies, tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug exposure, recent travel, and toxic exposures.

Onset

Sudden onset of severe pain is very concerning and is assumed to be due to a surgical condition, until proven otherwise. Vascular emergencies such as mesenteric ischemia or a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection and intestinal perforation, or torsion of a viscus may all present this way. Sudden onset of severe pain with an unimpressive physical examination is typical for a vascular catastrophe or torsed organ. Nonsurgical causes of abrupt onset of abdominal pain include renal colic and myocardial infarction. The physician should determine what the patient was doing when the pain began. Pain related to eating may be secondary to peptic ulcer disease, gallbladder disease, or mesenteric ischemia (intestinal angina). Pain that began during physical activity may be caused by a rectus abdominal muscle tear and hematoma, or myocardial ischemia.

Progression of Pain

The physician should question the patient about whether the pain is constant or intermittent and, if constant, whether it has been increasing or decreasing in severity. Pain that begins slowly and gradually progresses is typical of an inflammatory or infectious process such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, or salpingitis. Pain that is improving over time is less likely to be surgical in nature.

Location

In addition to onset, location may be one of the most useful pieces of information in determining the etiology of pain. Visceral pain is perceived either as epigastric, periumbilical, or infraumbilical, depending on the embryologic origin of the involved organ. Visceral pain tends to be poorly localized and midline whereas parietal (somatic) pain tends to be well localized and unilateral. It is important to determine whether the location has changed over time or radiates to a distant site.

Character

The severity and character of the pain are important historical factors. Dull aching pain is more likely to be visceral, and sharp pain is more likely to be somatic. Crampy intermittent pain is often because of bowel obstruction. Colicky pain often indicates nephrolithiasis or gallstone disease. Severe tearing back pain is classic for aortic dissection.

Aggravating and Alleviating Factors

The patient should be asked about how the pain changes with food, movement, position, or medications. Pain that is intensified by the car ride to the hospital or other movement is indicative of peritoneal irritation. The pain of pancreatitis is often exacerbated by lying in the supine position. The pain of myocardial ischemia may be relieved with rest.

Associated Symptoms

The physician should determine the presence or absence of fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, hematemesis, hematochezia, melena, dysuria, or hematuria. It is important to ask women about abnormal or increased vaginal discharge or vaginal bleeding and to ask men about testicular or penile complaints (swelling or pain). When patients complain of vomiting and abdominal pain, it is useful to determine which came first. Typically, in surgical diseases, the abdominal pain almost always precedes the vomiting, whereas the converse is true in most cases of gastroenteritis and nonspecific causes. As both cardiac and pulmonary processes can present with abdominal pain, an appropriate history should include questions about the presence of chest pain, shortness of breath, or cough. Also, the patient should be asked about the presence of flank or back pain. Patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, or renal colic may have pain that radiates to these areas.

Previous Episodes

Previous episodes of the pain should be investigated. Chronic recurrent abdominal pain involves a wide differential diagnosis; when obtaining the history, it is important to try to identify triggers of the abdominal pain. If the patient has undergone diagnostic studies in the past, there may be no point in repeating the workup unless there is a significant change in symptomatology or an emergent concern. If pain is recurrent, it may be related to the menstrual cycle. Pain that begins 2 weeks after the start of the menstrual cycle is suggestive of mittelschmerz, but this remains more or less a diagnosis of exclusion.

Past Medical History

Cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and valvular disease place patients at higher risk for vascular diseases such as mesenteric ischemia, abdominal aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and myocardial infarction. A gynecologic history should be obtained, including menstrual history, history of sexually transmitted diseases, and previous ectopic pregnancy.

Past Surgical History

Previous abdominal surgeries place patients at greater risk for conditions such as bowel obstruction resulting from adhesions (2).

Medications

A medication history should be obtained, including prescription medications, over-the-counter preparations, herbal supplements, and steroid use. It is essential to investigate any recent use of antibiotics which increases the risk of developing a Clostridium difficile infection. Certain drugs place patients at higher risk for hepatitis and pancreatitis.

Social History

Alcohol abuse increases the risk of gastroinestinal (GI) bleeds, pancreatitis, hepatitis, and cirrhosis. Heroin withdrawal may present with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Cocaine and amphetamine use may increase the risk of mesenteric ischemia.

Other

Recent traumatic events such as motor vehicle collisions or blows to the abdominal wall or back can result in rectus sheath hematoma, intraperitoneal bleeding, duodenal hematoma, or traumatic pancreatitis. A history of recent food intake, sick contacts, and travel is important for patients with suspected gastroenteritis. Finally, a history of any toxic exposures (e.g., lead) may also reveal the cause of the abdominal pain.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should always begin with an evaluation of the vital signs. When interpreting the vital signs, the emergency physician should take into account any medications that may affect heart rate or blood pressure (i.e., β-blockers). Tachycardia and hypotension should alert the physician to possible sepsis, dehydration from volume loss or third spacing, or hemorrhage from gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal aortic aneurysm, or ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Fever makes an infectious etiology more likely, although absence of a fever should not be used to rule out an infectious cause of the pain. This is especially true in the elderly or immunocompromised patient who may present with infectious etiologies, but no fever. Because an oral temperature may be falsely low owing to factors such as mouth breathing or consumption of cold liquids, the more reliable rectal temperature should be obtained if infection is suspected. Tachypnea may be secondary to pain, hypoxia, sepsis, anemia, or metabolic acidosis. Pulse oximetry should be obtained to assess for hypoxia.

The general appearance of the patient may reveal clues to the diagnosis. A patient with peritonitis will lie still whereas a patient with renal colic may present writhing in the bed. The patient’s level of alertness, mental status, and orientation are also important. Lethargy and confusion are concerning for toxic ingestions, sepsis, or other causes of hypoperfusion.

The patient’s skin should be carefully examined. Pale, cool, diaphoretic skin suggests shock or a low-volume state (dehydration or bleeding). Jaundice may be present in patients with biliary or hepatic disease. The skin should be examined for rashes. Skin findings such as petechiae and spider hemangiomas are suggestive of liver disease. Whether the mucous membranes are moist or dry should be noted; dry membranes suggest dehydration. Oral thrush or hairy leukoplakia may indicate undiagnosed immunocompromise.

When examining the heart and lungs, the physician should listen for rales, rhonchi, wheezing, or other abnormal breath sounds that indicate a pulmonary etiology of abdominal pain. The patient’s rhythm and the presence of murmurs should be noted, as atrial fibrillation and valvular disease put patients at risk for mesenteric ischemia caused by emboli.

The abdominal examination should start with inspection. The physician should look for distention, hernias, and the presence of surgical scars and auscultate for bowel sounds noting their frequency, quality, and pitch. Obstruction and processes that cause inflammation within the GI tract result in increased bowel sounds whereas processes that cause inflammation outside of the GI tract such as peritonitis result in diminished bowel sounds. With obstruction, high-pitched tinkling bowel sounds may be present; in patients with an ileus, bowel sounds may be absent. Percussion may aid in the diagnosis of ascites, obstruction, organomegaly, or perforation, and tenderness to percussion may indicate peritonitis.

When palpating the abdomen, the physician should assess for location of tenderness, the presence of voluntary and involuntary guarding, and peritoneal signs. It is recommended to begin with gentle palpation, starting farthest away from the suspected location of tenderness. If the patient is able to tolerate gentle palpation, then deeper palpation should be used to localize the area of tenderness. Palpation at one location may cause pain at a different location. An example of this is seen in patients with appendicitis and is referred to as Rovsing sign (pain experienced at McBurney point during deep palpation of the left lower quadrant). The physician should examine for masses or organomegaly. In assessing for RUQ pathology, the physician should note the presence of a Murphy sign. During deep palpation of the RUQ, the patient is asked to take a deep breath. If inspiration is arrested in midcycle, this is suggestive of cholecystitis (positive Murphy sign). In elderly patients, the physician should assess for an abdominal aortic aneurysm by listening for bruits and assessing for the presence of an infraepigastric pulsating mass.

Voluntary guarding may be due to anxiety, fear, or discomfort. Maneuvers that aid in relieving voluntary guarding include warming of the hands, examination with the patient’s thighs flexed, deep inspiration by the patient, and reassurance from the physician. Involuntary guarding or rigidity will not resolve with these maneuvers and is more indicative of surgical disease. Peritoneal signs are markers of surgical disease. Classically, peritonitis was assessed by examining for the presence of rebound tenderness, increased tenderness when the examiner let go after deep palpation of the abdomen. Rebound tenderness may be present even in the absence of peritonitis, and some advocate using other methods to look for peritonitis. These include the cough test (the abdominal pain will worsen abruptly when the patient coughs), jostling the gurney, or striking the patient’s heels to precipitate the pain. Rigidity and peritoneal signs may be absent in the elderly even in the presence of peritoneal irritation and surgical disease. This may be attributed to the relatively thin musculature of the abdominal wall in older patients.

Carnett’s test can be used to help determine whether abdominal pain arises from the abdominal wall. While in the supine position, the patient is asked to lift the head off the stretcher, and the abdomen is palpated. If the source of the pain is intra-abdominal, the contracted musculature of the abdominal wall will provide shielding and diminish tenderness. If the source of pain is the abdominal wall, the tenderness will be the same or even increased.

It is important to examine for umbilical, inguinal, femoral, and surgical incision hernias, especially in the elderly. In this age group, approximately 10% of cases of obstruction are due to hernias, and they are often undiagnosed.

Examination of the back is necessary to check for costovertebral angle tenderness that may indicate either pyelonephritis or ureteral obstruction.

Women of childbearing age with lower quadrant or suprapubic pain should undergo a pelvic examination to aid in differentiating salpingitis or ovarian pathology from appendicitis or diverticulitis. The results of the pelvic examination should be interpreted carefully, as women with appendicitis may also have cervical motion tenderness and adnexal tenderness. Adnexal or cervical motion tenderness suggests pelvic inflammatory disease; if present, mucopurulent discharge from the cervical os increases the likelihood. In women with RUQ pain, particularly if evaluation for gallbladder disease is negative, the pelvic examination may also be helpful. Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome, a perihepatitis caused by pelvic inflammatory disease, may present with complaints of right upper abdominal pain, and the patient may have no pelvic complaints. The diagnosis can be missed if the pelvic examination is not performed, especially as transaminases and other liver function tests are generally not elevated in this condition.

The digital rectal examination is helpful in assessing for a positive stool guaiac, melena, or hematochezia, and it may also aid in the diagnosis of prostate disease, perirectal disease, and rectal foreign bodies. A testicular examination should be performed to assess for torsion, epididymitis, or masses.

Patients with abdominal pain may remain in the ED for hours during their evaluation and workup. Repeat abdominal examination is very useful in these patients as changes over time may clarify the cause of their illness.

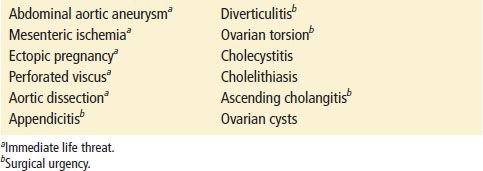

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain is extensive and includes both intra-abdominal and extra-abdominal sources of pain (Tables 7.1 and 7.2). A thorough history and physical examination are crucial in determining the etiology of the pain and narrowing down this vast list of possible causes.

TABLE 7.1

Surgical Causes of Abdominal Pain