CHAPTER 6. Extrication and Scene Management

Reneé Semonin Holleran

Competencies

1. Perform an initial scene evaluation to identify safety hazards.

2. Use the appropriate personal protective equipment.

3. Ensure that a patient has undergone decontamination before transport.

4. Identify who to call when hazardous materials have been spilled.

5. Demonstrate how to preserve evidence.

Extrication and scene management are important concepts for the transport team to thoroughly understand. Extrication, scene management, and hazardous material management exercises should be included in annual training for all transport personnel. The training officer of the local fire department or rescue team is an excellent resource for either joint agency training or training exclusively for transport personnel.

Air medical personnel are frequent participants in patient care in prehospital settings. Often, the rescue helicopter has been preceded by rescue personnel who have already freed trapped victims and secured them to backboards or triaged and decontaminated those exposed to hazardous substances. However, when extrication is prolonged or the helicopter is a first responder, air medical transport teams may need to use scene management and extrication skills. An important note is that only transport team members with the appropriate training and appropriate personnel protective equipment should participate in extrication. Technical rescues (including vehicle extrication, hazardous materials response, trench collapse, confined space, and rope rescue situations) for technical or heavy rescue companies are generally “high risk, low frequency” events that require coordinated, equipped, trained, and competent rescue personnel.

Most citizens and unskilled rescuers immediately rush to the victims. However, doing so can result in direct injury or exposure and contamination to both rescuers and victims and may delay the extrication and patient transport. Placement of a contaminated patient in a transport vehicle will result in that vehicle being taken out of service for decontamination.

SCENE MANAGEMENT

1. Evaluate the situation for potential safety hazards (e.g., utilities, gasoline, propane, fuel oil, water, sanitary systems, movement of vehicles, or release of high-pressure systems).

2. Secure the accident scene.

3. Wear personal protective equipment (PPE) appropriate to the hazards on the scene (e.g., gloves, goggles, or self-contained breathing apparatus [SCBA]).

4. Gain access to the patient.

5. Provide life-sustaining care to the patient.

6. Disentangle the patient from the vehicle.

7. Prepare the patient for removal from the accident scene (e.g., place cervical collar).

8. Remove the patient.

9. Prepare the patient for transport to the hospital.

10. Provide the patient with treatment en route.

When the rescue involves wilderness or back country rescue, the TOMAS mnemonic should be applied3:

T:Terrain (exposure, cliffs, water, forest, vegetation, hiking terrain, snow).

O:Obstacles (trees, loose rock, debris, wires, daylight, rotor wash, blade clearance).

M:Method (type of insertion and location, landing near or remote from patient, hover load).

A:Alternatives (wait for search and rescue [SAR], ferry SAR personnel, relocate patient, no go/abort mission).

S: Safety (first, last, always).

Scene evaluation begins when the communications center obtains information about possible problems and circumstances the rescuers may confront. The communication specialist should continue to seek information that could aid the rescuers throughout the incident, such as time of day, weather conditions, location, terrain, and number of victims. Information about fire, spilled fuel, toxic chemicals, overturned or entangled vehicles, and downed electrical lines should also be related to the communication specialist.

The general rule is to never compromise the rescuers to aid the victims. Even with appropriate protective equipment, rescuers are at risk of injury. 14 The utility company should secure downed electrical lines; the fire department contains and controls hazardous materials. The rescuer should read placards on heavy trucks or read the manifest in the truck cab to determine the presence of any toxic or radioactive materials.

Scene security is usually provided by law enforcement personnel. Onlookers and the media should be kept well back from the operation. The area should be appropriately secured by the referring agencies. 6

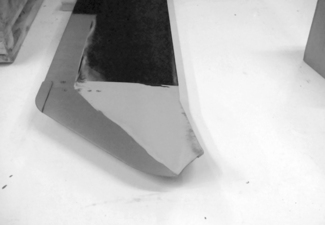

Proper placement of the helicopter is essential to avoid a second incident or hazard to personnel on the scene. The pilot retains the ultimate responsibility for landing the helicopter safely. Figure 6-1 shows a photograph of a tail rotor that was damaged when a vehicle drove under it in the dark and caused severe damage that put the aircraft out of service. Chapter 9 discusses scene landing recommendations.

|

| FIGURE 6-1 Tail rotor damage from a vehicle driving under it at a scene at night. Aircraft was out of service until the tail rotor was changed at the scene. |

EXTRICATION7,8

The transport team may enter a vehicle, once it is stabilized and deemed safe, through the car doors or by breaking out the glass and crawling through the windows. The transport team should not enter a vehicle unless trained or directed by a trained individual. Although one side of a vehicle may be crushed beyond recognition, the opposite-side car door may be operable. If the vehicle is lying on its side and access is gained through the top-side car door, rescue crews should stabilize the vehicle before entry to prevent any unexpected movement. Any unanticipated vehicle movement is both unacceptable and unsafe for rescuers and occupants.

Once inside the vehicle, the rescue team must perform rapid triage. Initial emergency treatment before extrication is extremely limited. Usually the initial-entry rescuer brings in a rigid cervical collar, a pocket facemask, and trauma dressings. The objectives are to: 1, establish and maintain an airway with cervical spine protection with either the chin-lift maneuver or the jaw-thrust maneuver; 2, provide artificial ventilation (if oxygen is used, caution must be exercised because an inadvertent spark can ignite fuel-saturated clothing); 3, control external hemorrhage; and 4, provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). CPR is not effective unless the patient is supine and on a firm surface; therefore, rapid extrication of the patient is needed for effective CPR. Patients who are apneic, pulseless, or unconscious or who have ineffective breathing must be removed quickly from the vehicle while manual cervical spine protection is maintained.

The basic principle of extrication is that the rescuers should remove the vehicle from the victim rather than the other way around. If the vehicle is on its side, the extrication is performed through the roof. If the vehicle is on its wheels or roof, extrication is conducted through the doors. Rescue personnel inside an upright vehicle should first unlock the doors and use interior handles while their partners use exterior handles to open the doors. Before proceeding with patient extrication, rescue personnel should always ensure the vehicle’s emergency brake is engaged, the key/engine is turned off, the transmission is placed in park, and, whenever possible, the vehicle’s battery is disconnected.

Once the doors are open, victims can be secured to short backboards that provide spinal column immobilization. Further obstacles to extrication may occur. Typically, a victim’s thorax becomes wedged between the forward-displaced seat and the rearward-displaced steering wheel/column, or a victim’s feet and legs become trapped under the downward-displaced dashboard and the accelerator or brake pedal. A quick option to create more room between the victim, the seat, and the steering wheel is to manually slide the seat back, if it remains operational. Multiple rescuers should control the seat and the patient to avoid unnecessary movement and possible risk of further injury.

The victim must be completely immobilized if the seat has been torn from the mechanical track. When the seat tracks snap, a series of physically jarring pops usually occurs that could substantially compromise an injured victim’s condition.

Pulling the steering wheel usually disentangles the victim’s legs and feet because it concurrently lifts the dashboard up and forward.

If the vehicle is resting on its side and has been stabilized, extrication can be achieved by cutting an upside-down U in the roof. The vehicle should be stabilized in the side position, the occupants should be warned of the very loud noise about to begin, and a heavy aluminized blanket should cover the occupants for their safety. After the three-sided U-shaped cut of the roof is made, the metal flap should be folded down to provide a smooth edge to move the victims across on their way out. 7

AIR BAGS

Rescuers must also be aware of the hazard of air bags. Most recently built cars are equipped with these safety devices. Studies have documented the effectiveness of air bags in decreasing serious injuries to drivers and passengers. 1,7,10 However, air bags can also cause injuries such as facial abrasions and lacerations and contusions to the chest and upper extremities. 1,8,10

Undeployed air bags may be a potential hazard to the rescuer and can cause injuries similar to those reported in accidents in which the air bag has deployed. If the air bag has not been deployed, the rescuer should observe the following precautions1,8,10:

1. Disconnect or cut both battery cables. Always cut or disconnect the negative side first. Secure both cables so they do not spring back and touch each other or the battery.

2. Avoid placing personnel or objects in front of the air bag deployment path.

3. Do not mechanically displace or cut through the steering column until the system has been deactivated. Charts are available that indicate how long the airbag may take to deactivate. Some may take up to 30 minutes.

4. Do not cut or drill into the air bag module.

5. Do not apply heat in the area of the steering wheel hub.

6. Be aware of other air bags within the vehicle (e.g., the side air bag).

AIRCRAFT CRASH

The crash of even a light aircraft requires the response of a variety of emergency service units, including fire, rescue, emergency medical service (EMS), and law enforcement. For quick and effective response, the person who reports a crash must provide as much information about the incident as possible.

The following information should be obtained by communication center personnel and relayed to responders:

1. The time of the crash.

2. The type of aircraft (e.g., small passenger plane, commuter aircraft, large commercial jet, military transport plane, military fighter aircraft, or helicopter).

3. The number of engines, if known.

4. Whether the wreckage is on fire.

5. Whether a parachute was observed.

6. The number of occupants of the aircraft, if known.

7. Identification numbers and markings of the aircraft. Military aircraft are marked “US Air Force,” “US Navy,” and so forth. Commercial aircraft show the name of the carrier. Private aircraft may have a combination of letters and numbers that constitute the identification number.

8. The status (e.g., on fire, damaged, or collapsed) of any structures struck by the aircraft or its components.

9. The status of people in those structures, if known.

10. Vehicles that were struck by the aircraft or parts of it and the status of any persons inside the vehicles, if known.

11. Structures that appear to be endangered by encroaching fire, spilled fuel, military ordnance, and so on.

If the transport team arrives at the crash site before emergency service units, team members must proceed with caution. Survivors of the crash or persons who have been ejected or who have parachuted from the aircraft may be lying on the roadway leading to the crash site. If the aircraft is military, crew members must avoid both the front and rear ends of any externally mounted tanks or pods because these may be containers for missiles or rockets. The crew must be careful not to disturb any armament thrown clear of the aircraft; it may explode if improperly handled. No one should move body parts or components of the aircraft unless movement is necessary to care for injured persons. When emergency service units arrive on the scene, the transport team should report to the officer-in-charge everything known about the incident and the locations of any injured persons who have been assisted.

BUS CRASH8

Stopping the Engine

Buses equipped with diesel engines do not need electrical power once they have been started. If possible, the rescuers should stop the engine by using the emergency stop button located on the driver’s left-hand side switch panel. If the engine does not stop with this button, a crew member should discharge CO 2 into the engine air intake located at the left rear corner of the coach, discharging the agent inward and toward the front of the coach. Dry chemical should not be used. Not all buses may be equipped this way.

Entering the Coach

The rescuers should enter the coach through the front door if possible, but only after the vehicle is stabilized. Door unlocking and unlatching mechanisms can be found under the right-side wheel well, behind the front medallion, or to the left of the driver’s seat, depending on the make and model of the bus. If the rescuers cannot enter through the front door, they can enter the bus through the windshield by removing the rubber locking strip from around the pane and then removing the pane. To enter the restroom (if the bus is equipped with one), the rescuers should open the small flap at the right rear window and lift the latch bar to open the window.

If the bus is lying on its side, entry may be possible through a roof access hatch or rear emergency window. Bus accidents are likely to overwhelm local rescue resources because of the high number of potential victims. Rescuers should be prepared to perform triage on passengers who remain inside the bus with the Simple Triage and Rapid Transport (START) triage system (RPM: Respirations, Pulse, and Motor) or an appropriate alternative. Removal of patients on stretchers requires a coordinated team effort to prevent further injury to patients or risk of injury to rescuers.

The Air Suspension System

The transport team must remember the warning to not place heads or extremities under any portion of the coach until it is securely stabilized.. The air suspension system bellows may deflate without warning, in which case the body of the coach may drop suddenly to within inches of the roadway.

ELECTRICAL EMERGENCIES12

High voltages are common on roadside utility poles. Wooden poles are sometimes used to support conductors of as much as 500,000 V. Energized downed lines may or may not arc and burn. No assurance can be given that a dead line at the scene of a vehicle accident will not become energized again unless it is cut or otherwise disconnected from the system by a representative of the power company. When an interruption of current flow is sensed in most power distribution systems, automatic devices restore the flow two or three times over a period of minutes.

The dispatcher should advise the power company of the exact location of the accident and the number of the power pole. The rescue team member designated to control bystanders should order spectators and nonessential personnel to leave the danger zone. The power company is responsible to ensure all power has been disconnected from energized lines. Depending on the distances between poles, the danger zone may be as large as 600 ft by 1500 ft. Any rescuer should stop the approach immediately if a tingling sensation is felt in the legs and lower torso. This sensation signals energized ground; current is entering through one foot, passing through the lower body, and leaving through the other foot. This current flow is possible because of the condition known as ground gradient, which means the voltage is greatest at the point of contact with the ground and then diminishes as the distance from the point of contact increases.

If a tingling sensation is felt, the proper procedure is to bend one leg at the knee and grasp the foot of that leg with one hand, turn around, and hop to a safe place on one foot. This maneuver ensures that the body does not complete a circuit between sections of ground energized with different voltages. The rescuer and the transport team should then stand by in a safe place until a representative of the power company can cut the lines or otherwise disconnect them from the power distribution system. The crew member who controls access to the scene must discourage ambulatory accident victims from leaving their vehicles until conductors that are either touching or surrounding the wreckage can be deenergized.

Metal or Conducting Fences

A lethal current can be conducted through a chain-link fence for some distance. If working near or climbing a chain-link fence that may be energized by a downed conductor is necessary, a crew member should not approach the fence with arms extended and fingers pointing forward. If contact is made with an energized fence, the current will cause the person’s fingers to curl around the fence mesh and hold the person in place.

If a fence is thought to be energized, personnel should stay a safe distance away and establish a safe perimeter and then wait for the power company to secure the area and contain the power.

The proper approach to the fence is with arms extended and the backs of hands facing forward. If the fence is energized, the current will cause the person to be repelled backward.

HAZARDOUS MATERIALS EMERGENCIES11,14

Emergencies that involve hazardous materials occur in all areas of the United States, and transport teams are likely to be involved in the care of those who have been injured. When a hazardous material can be identified from a number or by name, emergency service personnel may obtain advice about the emergency from agencies that assist in the management of hazardous materials (Box 6-1). Agencies such as the Chemical Transportation Emergency Center (CHEMTREC) and the US Department of Transportation can offer specific information.

BOX 6-1

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Agencies That Assist in Hazardous Materials and Potential Rescue Incidents

Federal Agencies

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Department of Transportation (DOT)

National Response Center (NRC)

United States Coast Guard (USCG)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree