Disorders affecting 12-lead ECGs

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is a key tool in diagnosing and evaluating certain disorders, such as angina, Prinzmetal’s angina, myocardial infarction (MI), pericarditis, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), and bundle-branch block (BBB). In some disorders, such as angina, ECG changes are fleeting, making a quick response crucial to diagnosis. In other disorders, such as MI, subtle ECG changes could signal a life-threatening complication. Take time to become familiar with these disorders and the ECG changes they produce. Doing so allows you to respond promptly to changes in the patient’s condition.

Angina

During an episode of angina, the myocardium demands more oxygen than the coronary arteries can deliver. An episode of angina usually lasts between 2 and 10 minutes. If the patient’s pain persists as long as 30 minutes, he’s more likely suffering from an MI than angina.

Angina is classified as an acute coronary syndrome. Types of angina include stable angina—which occurs in a predictable, repetitive pattern—and unstable angina—which commonly signals an impending MI.

Causes

Narrowing of the arteries from coronary artery disease (CAD) restricts the amount of blood flowing to the myocardium. Platelet clumping, thrombus formation, and vasospasm may further restrict blood flow. When conditions arise in which the myocardium demands more oxygen than the narrowed arteries can supply—such as exertion, stress, or even a large meal—myocardial ischemia and pain result.

Clinical significance

Stable angina suggests a narrowing of the coronary arteries, usually resulting from atherosclerosis. If ignored, the arteries may continue to narrow, eventually leading to unstable angina.

Unstable angina is considered a medical emergency because its onset usually indicates an MI.

ECG characteristics

Most patients with either form of angina show ischemic changes on an ECG only during an attack. Because these changes may be fleeting, obtain an order for, and perform, a 12-lead ECG as soon as the patient reports chest pain. Once obtained, the ECG can reveal the area of the heart being affected. By recognizing danger early, you may possibly prevent an MI or even death. (See ECG changes associated with angina.)

Signs and symptoms

In stable angina, patients describe the pain as substernal or precordial burning, squeezing, or tightness. The pain may radiate to the left arm, neck, or jaw. Triggered by exertion or stress, the pain is typically relieved by rest. Each episode of stable angina follows the same pattern.

Unstable angina, on the other hand, is more easily provoked, commonly waking the patient. Compared with stable angina, the pain is more intense, lasts longer, and may not radiate. The episodes of pain are also unpredictable and worsen over time. During an attack, the patient’s skin may be become pale and clammy,

and he may complain of feeling nauseous and anxious.

and he may complain of feeling nauseous and anxious.

Interventions

Drug therapy is a key component of angina treatment. Nitrates help reduce myocardial oxygen consumption, while beta-adrenergic blockers reduce the heart’s workload and oxygen demands. Patients with angina caused by coronary vasospasm typically receive calcium channel blockers. Antiplatelet drugs may be given to minimize platelet aggregation and reduce the risk of coronary occlusion. Antilipemic drugs may also be given to help lower elevated serum cholesterol or triglycerides levels.

If the patient has continued unstable angina or acute chest pain, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors may be given to reduce platelet aggregation. Coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty may be performed to remove obstructive lesions.

Prinzmetal’s angina

Prinzmetal’s angina is a relatively uncommon form of unstable angina. Ischemic pain usually occurs at rest or awakens the patient from sleep. Pain doesn’t follow physical activity or emotional stress.

Causes

Prinzmetal’s angina results from a focal episodic spasm of a coronary artery, with or without an obstructing coronary artery lesion. Cocaine use has been implicated as one possible cause of Prinzmetal’s angina.

Clinical significance

Besides causing episodes of disabling pain, Prinzmetal’s angina may lead to ventricular arrhythmias, atrioventricular block, MI and, rarely, sudden death.

ECG characteristics

Rhythm: Atrial and ventricular rhythms are normal.

Rate: Atrial and ventricular rates are within normal limits.

P wave: Normal size and configuration.

PR interval: Normal.

QRS complex: Normal.

ST segment: Marked elevation in leads monitoring the area of coronary spasm. This elevation occurs during chest pain and resolves when pain subsides.

T wave: Usually of normal size and configuration.

QT interval: Normal.

Other: None.

Signs and symptoms

A patient with Prinzmetal’s angina typically experiences substernal chest pain ranging from a feeling of heaviness to a crushing discomfort, usually while at rest. He may also experience dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, and arrhythmias.

Interventions

Acute management includes the administration of nitroglycerin (Nitro-Bid), which should provide prompt relief from pain by dilating the coronary arteries. For chronic management, long-acting nitrates and calcium channel blockers may be used to help prevent coronary artery spasm. Patients with obstructing coronary artery lesions may benefit from revascularization.

Myocardial infarction

Categorized as an acute coronary syndrome, MI occurs when reduced blood flow through one or more coronary arteries causes myocardial ischemia, injury, and necrosis. Damage usually occurs in the left ventricle, although the location varies depending on the coronary artery affected. For as long as the myocardium is deprived of an oxygen-rich blood supply, an ECG will reflect the three pathologic changes of an MI: ischemia, injury, and infarction.

Causes

Causes of MI include atherosclerosis and embolus. In atherosclerosis, plaque (an unstable and lipid-rich substance) forms and subsequently ruptures or erodes, resulting in platelet adhesions, fibrin clot formation, and activation of thrombin.

Risk factors for MI include:

diabetes

family history of heart disease

high-fat, high-carbohydrate diet

hyperlipoproteinemia

hypertension

menopause

obesity

sedentary lifestyle

smoking

stress.

Clinical significance

The location of the MI is a key factor in determining the most appropriate treatment and in predicting probable complications. Locations include the anterior wall, septal wall, lateral wall, inferior wall, posterior wall, and right ventricle.

Anterior wall

The left anterior descending artery supplies blood to the anterior portion of the left ventricle, ventricular septum, and portions of the right and left bundle-branch systems. When the left anterior descending artery becomes occluded, an anterior-wall MI occurs. Complications include second-degree AV blocks, BBBs, ventricular irritability, and left-sided heart failure.

Septal wall

The patient with a septal-wall MI is at increased risk for developing a ventricular septal defect. Because the left anterior descending artery also supplies blood to the ventricular septum, a septal-wall MI typically accompanies an anterior-wall MI.

Lateral wall

Inferior wall

An inferior-wall MI commonly results from occlusion of the right coronary artery. This type of MI may occur alone or with a lateral-wall or right-ventricular MI. Patients with inferior-wall MI risk developing sinus bradycardia, sinus arrest, heart block, and PVCs.

Posterior wall

A posterior-wall MI results from occlusion of the right coronary artery or the left circumflex arteries. Posterior infarctions may accompany inferior infarctions.

Right ventricle

A right-ventricular MI usually follows occlusion of the right coronary artery. This type of MI rarely occurs alone. In 40% of patients, a right-ventricular MI accompanies an inferior-wall MI. A right-ventricular MI can lead to right ventricular failure.

ECG characteristics

As myocardial cells undergo ischemia and necrosis, they become unable to depolarize normally. In turn, this produces several ECG abnormalities, including the appearance of a Q wave as well as changes in the ST segment and the T wave.

Q wave: The cardinal ECG change associated with an area of myocardial necrosis (called the zone of infarction) is a pathologic Q wave. The pathologic Q wave results from a lack of depolarization in the necrotic area. Eventually, scar tissue replaces the dead tissue, making the damage, and the resultant Q waves, permanent. Some MIs, however, don’t produce Q waves; they’re called non–Q-wave MIs.

ST segment: ST-segment elevation results from a prolonged lack of blood supply to the zone of injury, which surrounds the zone of infarction. (In a non–Q-wave MI, abnormalities may include non–ST-segment elevation or ST-segment depression.) The ST-segment typically elevates at the onset of an MI—indicating that myocardial injury is occurring—and then returns to baseline within 2 weeks.

T wave: T-wave inversion results from ischemia to the outermost area of the zone of infarction, which is called the zone of ischemia. When ischemia persists and injury begins, T waves generally flatten and eventually invert. Inverted T waves may persist for several months, but they eventually return to their upright position.

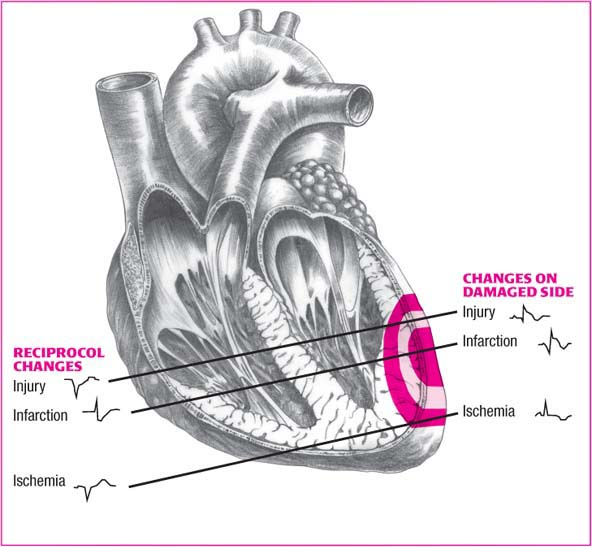

Reciprocal changes in MI

Ischemia, injury, and infarction—the three “Is” of myocardial infarction (MI)—disrupt normal depolarization and produce characteristic electrocardiogram changes. These changes arise in the leads reflecting electrical activity in the damaged areas (shown on the right side of the illustration below).

Reciprocal changes occur in leads opposite the damaged areas. These changes are shown on the left side of the illustration.

|

Leads showing ECG changes

The leads showing the changes characteristic of an MI will vary, depending on the area of infarction. (See Reciprocal changes in MI and Locating myocardial damage, page 272.)

Anterior-wall MI

An anterior-wall MI causes characteristic ECG changes in leads V2 to V4. Because the left ventricle can’t depolarize normally, the precordial leads show poor R-wave progression, ST-segment elevation, and T-wave inversion. The reciprocal leads for the anterior

wall are the inferior leads II, III, and aVF. They initially show tall R waves and depressed ST segments. (See Recognizing an anterior-wall MI.)

wall are the inferior leads II, III, and aVF. They initially show tall R waves and depressed ST segments. (See Recognizing an anterior-wall MI.)

Locating myocardial damage

After you’ve noted characteristic lead changes in an acute myocardial infarction, use this table to identify the areas of damage. Match the lead changes (ST elevation, abnormal Q waves) in the second column with the affected wall in the first column and the artery involved in the third column. The fourth column shows reciprocal lead changes.

| WALL AFFECTED | LEADS | ARTERY INVOLVED | RECIPROCAL CHANGES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | V2, V3, V4 | Left coronary artery, left anterior descending (LAD) | II, III, aVF |

| Anterolateral | I, aVL, V3, V4, V5, V6 | LAD and diagonal branches, circumflex and marginal branches | II, III, aVF |

| Anteroseptal | V1, V2, V3, V4 | LAD | None |

| Inferior | II, III, aVF | Right coronary artery (RCA) | I, aVL |

| Lateral | I, aVL, V5, V6 | Circumflex branch of left coronary artery | II, III, aVF |

| Posterior | V8, V9 | RCA or circumflex | V1, V2, V3, V4 (R greater than S in V1 and V2, ST-segment depression, elevated T wave) |

| Right ventricular | V4R, V5R, V6R | RCA | None |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree