CHAPTER 15 WOUND BALLISTICS: WHAT EVERY TRAUMA SURGEON SHOULD KNOW

Although most trauma centers in the past two decades have experienced a reduction in the volume of firearm-related injuries, trauma and general surgeons still have an obligation to be familiar with the basic principles of ballistics and the management of the varieties of wounds that projectiles produce. Wounds caused by firearms will not only be encountered in urban “high-crime” areas, but will also be seen in rural areas where hunting accidents occur. Wounds encountered in a military environment have unique characteristics that are clinically important and distinct from those seen in the civilian sector. The study of wound ballistics is an essential part of the general and trauma surgeon’s training.

FIREARM AND PROJECTILE DESIGN

Although there are many variables, the muzzle velocity (speed of the bullet as it leaves the barrel) and the bullet characteristics such as mass and deformability are the most important determinants of the wound that a particular weapon will produce (Table 1). The muzzle velocity is determined by the caliber of the bullet, the capacity of the casing (amount of powder), and gun barrel length. The bullet’s velocity rapidly increases as it travels down the barrel, but gradually slows upon meeting air resistance once it has exited. Handguns generally accept smaller bullets with less powder and have shorter barrels than rifles, and therefore produce projectiles of considerably less velocity (Table 2).

Table 1 Factors Involved in Wound Ballistics

| Bullet Design |

| Caliber (diameter) |

| Mass |

| Shape (profile) |

| Jacket |

| Pellets |

| Powder (amount and type) |

| Weapon Design |

| Barrel length |

| Rifling |

| Single shot |

| Automatic |

| Semi-automatic |

| Portability (weight and size) |

| Victim |

| Position |

| Distance from weapon |

| Location of wound |

| Tissue characteristics (bone, muscle, vessel, organ) |

Table 2 Muzzle Velocity by Gun and Bullet Type

| Handguns | M/sec |

|---|---|

| .38 special | 290 |

| .44 | 305 |

| 9 mm | 315 |

| .44 magnum | 420 |

| Rifles | |

| .22 long | 380 |

| 30.06 | 890 |

| .308 (7.62 mm) | 860 |

| Military | |

| .223 (M-16) | 950 |

| .30 (AK-47) | 720 |

| .50 (Browning) | 850 |

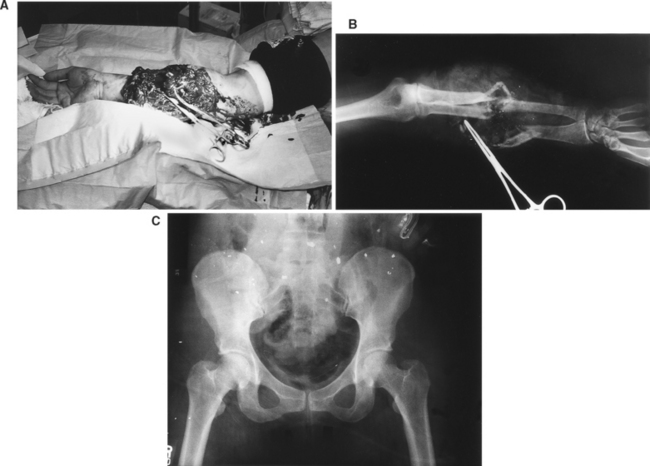

The mass of the bullet is determined by its caliber (diameter), length, and the density of its metal components. Because of its heavier mass, and therefore its increased energy per given velocity, lead is the principal element of most bullets. Lead, however, is a relatively soft metal that deforms readily during high-velocity flight. “Jacketed” bullets have a lead body covered with metal alloys that prevent deformation during flight, and therefore help the bullet retain speed and accuracy over a long distance. Conventionally jacketed bullets will deform when they strike dense tissue, but bullets with thicker jackets are intended to retain their shape and therefore penetrate deeply into large game animals such as elephants (Figure 1). Bullets that deform upon striking the body will cause considerably more collateral tissue damage by direct contact, cavitation, and shock waves than nondeformable bullets. Fragmentation of bullets will also occur when the bullet strikes bone and will add to the damage by shredding surrounding tissue (Figure 2).

HANDGUNS

Nonetheless, several measures designed to increase the wounding potential or “stopping-power” of handguns are available and will be encountered. These include “hollow-point” bullets designed to expand (Figure 3, right) and Glaser Safety Slugs® designed to disintegrate into tiny pellets after impact (Figure 4). The Glaser Safety Slug® is marketed to law enforcement and security personnel who need to immobilize a human target in a crowded environment such as an airport or an airplane without concern of overpenetration or ricochet into innocent bystanders. “Magnum” handguns have extra powder and longer barrels that will produce a devastating wound at close range. Fortunately, magnum editions are not as commonly seen as regular handguns because they are expensive, heavy, and difficult to master.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree