203 White Blood Cell Disorders

• White blood cell disorders are the result of cell overproduction, underproduction, or dysfunction.

• Hematologic malignant diseases have variable initial presentations and significant associated complications.

• Rapid evaluation and intervention are essential to minimize morbidity and mortality in the immunocompromised patient.

Epidemiology

The National Cancer Institute estimated that approximately 137,260 new cases and 54,020 deaths from hematologic malignant diseases (leukemias, lymphomas, and plasma cell disorders) occurred in 2010. On January 1, 2007, approximately 908,512 men and women living in the United States had a history of hematologic malignant disease. In adults, non-Hodgkin lymphomas and chronic lymphocytic leukemia are the most common of these diseases.1 Of a total of 26,446 childhood cancers (age 1 to 19 years) diagnosed in the United States from 2001 to 2003, leukemias were the most common (26.3%). The lymphoid leukemias were the type with the highest incidence. Lymphomas, comprising 14.6% of new childhood malignant diseases, were the third most common cancers.1,2 A history of malignant disease is a common feature in the emergency department (ED) patient population. In a retrospective review of 5640 patients in a community teaching hospital with an annual ED census of 31,000, cancer history was identified in 5% of patients. Ten percent of patients with oncology-related visits died during the admission, and 48% died within 1 year of the ED visit.3

Pathophysiology

White blood cells (WBCs), or leukocytes, are the primary cells responsible for the inflammatory and immune response. WBCs include granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils) and mononuclear cells (T and B lymphocytes, monocytes). These cells are all produced from a common stem cell in the bone marrow, and they differentiate through various cytokines including colony-stimulating factors and interleukins. Normal blood leukocyte counts are 4.34 to 10.8 × 109/L, with neutrophils representing 45% to 74% of cells, bands representing 0% to 4%, lymphocytes representing 16% to 45%, monocytes representing 4% to 10%, eosinophils representing 0% to 7%, and basophils representing 0% to 2%.4 WBC disorders are the result of cell overproduction, underproduction, or dysfunction (Box 203.1). The WBC count with differential lacks specificity and sensitivity but is the most frequent laboratory test ordered by emergency physicians.5

Box 203.1

Differential Diagnosis of White Blood Cell Disorders by Pathogenesis

Adapted from Lepin HD, Powell BL. White cell disorders. In: Halter JB, Ouslander J, Tinetti M, et al, editors. Hazzard’s geriatric medicine and gerontology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

Leukopenia

Leukopenia, or a WBC count less than 1.5 × 109/L, is most clinically relevant with significant neutropenia and its complications (primarily increased risk of infection, further outlined in Chapter 201). Although neutropenia is most common in patients with bone marrow suppression secondary to chemotherapy, Box 203.2 outlines a differential diagnosis of certain infections that characteristically manifest with neutropenia. Lymphocytopenia is a nonspecific finding that is present in many bacterial, fungal, viral, and protozoan infections.6

Leukocytosis

Leukocytosis, or an increased number of WBCs, is defined as an elevation in the total number of circulating WBCs greater than 2 standard deviations above the age-based mean circulating WBC count. This disorder is most commonly secondary to infections or systemic stressors; however, an increase in a subset of WBCs (neutrophilia, monocytosis, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, or basophilia) may guide the differential diagnosis. Bacteria are the culprit in two thirds of infection-related cases of neutrophilia.7 Box 203.3 outlines infectious causes of lymphocytosis, with Bordetella pertussis being the rare bacterial exception. Eosinophilia is classically caused by multicellular parasites that invade tissue, most commonly seen in invasive parasitic disease, but it may also be seen in protozoan and fungal infections.8

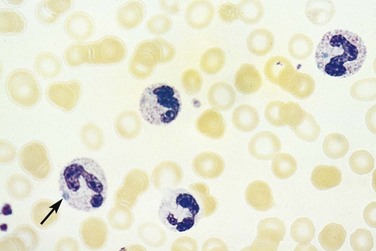

Morphologic Changes

In addition to altered numbers, changes in cellular morphology found in a peripheral blood smear may aid in the diagnosis. A left shift (or greater percentage of immature cells, such as metamyelocytes) may be present in severe infection. Intracellular abnormalities including toxic granulations, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and Dohle bodies are likely secondary to infection (Fig. 203.1).6

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Acute Myelogenous and Lymphoid Leukemias

Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

Patients with leukemia present with signs and symptoms secondary to the invasion of other organs by leukemic cells and decreased production of normal hematopoietic cells. Fever, malaise, and a viral-like syndrome are common presenting symptoms. Diffuse bony tenderness, as a result of expansion of the intramedullary space or periosteal infiltration by leukemic cells, is the initial symptom in 25% of patients.9

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) typically affects all three cells lines and results in anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia. Pallor, dyspnea, and chest pain reflect anemia, whereas petechiae, ecchymosis, and excessive bleeding are a result of thrombocytopenia. One third of patients will have significant infections on diagnosis.10 Splenomegaly occurs in up to 50% of patients, and lymphadenopathy is rare.9

AML has several skin manifestations. Raised, nontender plaques or nodules (leukemia cutis) are manifest in many forms of leukemia, but they are most commonly seen in AML (Fig. 203.2).11 Tender, pseudovesicular, erythematous plaques are a characteristic feature of Sweet syndrome, which may precede the diagnosis of AML by months (Fig. 203.3). Gingival hyperplasia may also be present (Fig. 203.4).

Fig. 203.2 Leukemia cutis in a patient with monoblastic leukemia.

(From Miller KB, Pihan G. Acute myeloid leukemia. In: Hoffman R, Benz Jr EJ, Shattil SJ, et al, editors. Hematology: basic principles and practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.)

Fig. 203.3 Sweet syndrome in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia.

Tender, pseudovesicular, erythematous plaques are a characteristic feature of this syndrome.

(From Cohen PR. Acral erythema: a clinical review. Cutis 1993;51:175, with permission.)