Fig. 31.1

(a) Chest x-ray of index patient on admission day 3. (b) Telemetry monitor showing the patient’s vital signs on admission day 3. (c) Mechanical ventilator parameters of the index patient on admission day 3

Question

What approach would best determine her readiness for liberation from the mechanical ventilator?

Answer

Spontaneous breathing trial (SBT)

All intubated patients should be assessed with a SBT to determine their readiness for liberation from the mechanical ventilator after the underlying cause for intubation has been addressed and is improving. The patient had been ventilated on small tidal volumes (6 ml/kg ideal body weight) and her plateau airway pressures ranged between 20 and 24 cmH2O. Her PaO2/FiO2 ratio remained >200 with a PEEP of 5cmH2O and FiO2 of 40 %. Her hemodynamic status remained stable with no requirement for vasopressor support. She received an analgesic infusion of fentanyl, which was interrupted on a daily basis to assess her mental function. Physical and occupational therapy were commenced within 24 h of her ICU admission and she was maintained on a daily negative fluid balance of 1–2 L per day. Her most recent arterial blood gas was 7.32/42/75/98 and she had minimal airway secretions. Continuous sedation was discontinued and while she was awake, a 30-min spontaneous-breathing trial was performed with CPAP of 5 cm of water and her observed vital signs afterwards are depicted in Fig. 31.2.

Fig. 31.2

Telemetry monitor showing the patient’s vital signs after a 30-min spontaneous breathing trial

Principles of Management

Strategies to Minimize the Requirement for Mechanical Ventilation

Various disease states predispose patients to respiratory failure ultimately requiring mechanical ventilation for respiratory support. In patients with sepsis, the need for mechanical ventilation may be prevented by instituting early aggressive resuscitative measures [1]; however, this protocol-based care may not result in improved outcomes [2, 3]. Similarly, instituting non-invasive ventilation in patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema or acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease could reduce the need for intubation and mechanical ventilation in these patients [4–7].

Strategies to Reduce the Duration of Mechanical Ventilation

Once a patient has been intubated, several strategies which could speed up readiness for liberation from mechanical ventilation include the use of lung protective ventilation in ARDS [8], interruption of sedatives on a daily basis [9], implementing physical and occupational therapy early [10], conservative fluid management in ARDS [11] and the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia [12].

Evaluation of Patient’s Readiness for Spontaneous Breathing

Patients determined to be ready for a trial of spontaneous breathing should exhibit improvement in the underlying factors that led to respiratory failure and be hemodynamically stable with a ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to the fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) that exceeds 200 on a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5 cmH2O or less [13].

Perform a Spontaneous Breathing Trial in Patients Deemed Ready

An SBT is performed to demonstrate the patient’s ability to breathe on minimal or no ventilator support for at least 30 min. Usually, this is performed on continuous positive airway pressure, low-level pressure support or utilizing a T-piece. The occurrence of oxygen saturation ≤90 %, heart rate >140/min, respiratory rate >35/min for more than 5 min, a sustained variation of 20 % or more in the heart rate, systolic blood pressure below 90 mmHg or exceeding 180 mmHg, increase in anxiety or diaphoresis all portend failure [13].

Assess Patient’s Ability to Protect the Airway

A successful trial of spontaneous breathing will lead to an evaluation of the patient’s ability to effect airway protection upon removal of the endotracheal tube. This assesses the patient’s mentation, strength of cough and quantity of airway secretions. Demonstration of adequate unassisted breathing and airway protection should prompt immediate removal of the endotracheal tube. Otherwise, if SBT is unsuccessful, re-initiation of mechanical ventilation at the prior support level should be ensured while a careful investigation is performed to determine and treat the underlying reason for failure before repeating an evaluation for a trial of spontaneous breathing again [13].

Evidence Contour

Assessing the Need for an Artificial Airway

Demonstration of some capability to interact with the health care team is required prior to removal of the patient’s endotracheal tube. However, the exact significance and the degree to which it plays a role in successful extubation remain controversial [14]. It has been suggested that in patients capable of protecting their airway, a Glasgow coma scale score of ≥8 predicts successful extubation [15]. Prolonged mechanical ventilation, female sex and traumatic or repeated intubation have all been associated with post-extubation upper airway obstruction [16] leading to suggestions for the use of the cuff leak test (air leak detection during mechanical ventilation with a deflated endotracheal tube balloon) in these patients to assess the patency of the upper airway prior to extubation [17]. Patients at high risk of post-extubation stridor were identified in a single study of intubated medical patients using a cuff leak of <110 ml within 24 h of extubation [18]. Steroids and/or epinephrine may be used during this period to reduce the risk or for treatment in those patients who develop stridor afterwards [19]. The use of NIPPV and/or heliox has also been advocated [19].

Weaning Protocols

The use of weaning protocols enforces daily evaluation of readiness for extubation by using pre-specified criteria and implementing trial of spontaneous breathing in a structured form. The WEAN study, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial which compared automated weaning with the use of a standardized protocol demonstrated significantly faster liberation from mechanical ventilation and fewer cases of protracted ventilation or tracheostomies [20]. Similarly, a large Cochrane meta-analysis of ten trials compared automated weaning protocols and non-automated weaning strategies and demonstrated a decrease in the duration of mechanical ventilation, time to successful extubation, ICU length of stay and proportion of patients on mechanical ventilation for more than 7 days in patients on a protocolized weaning strategy [21]. Though yet to be widely adopted, this automated strategy possibly ensures all mechanically ventilated patients are given a fair chance to demonstrate their ability for spontaneous breathing at the earliest time (Figs. 31.3 and 31.4).

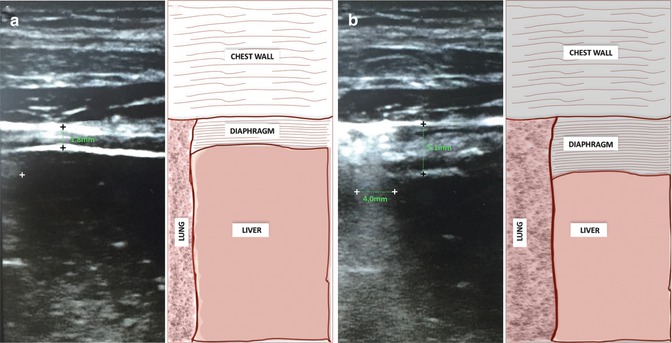

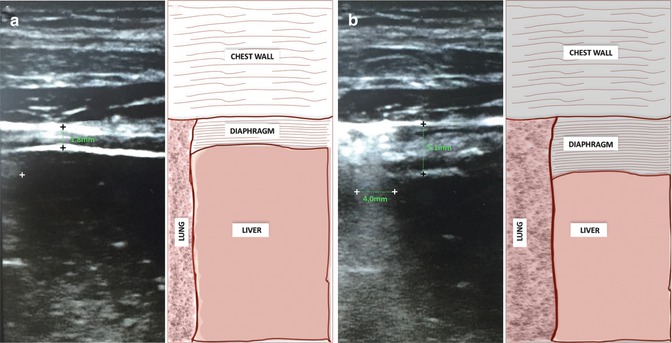

Fig. 31.3

A high resolution 13–6 MHz ultrasound linear probe (SonoSite Edge, SonoSite, Inc., Washington USA) held perpendicular to the chest was used to evaluate real-time movement of the diaphragm in the zone of apposition. Measurements obtained were recorded in B mode (two dimensional) ultrasonography by placing the transducer along the line of an intercostal space between the right anteroaxillary and midaxillary lines to ensure the zone of apposition is visualized ~0.5–2 cm below the right costophrenic sinus. Air in the lungs facilitates easy detection of the inferior border of the sinus and the two bright parallel lines of its peritoneal and pleural membranes identify the diaphragm with an intervening muscular layer during maximal expiratory effort (a) and maximal inspiratory effort (b). Ultrasonographic measurements of diaphragmatic thickening (black crosses) and hepatic displacement (white crosses) during spontaneous breathing trials have been demonstrated to be useful in predicting extubation outcomes [22–24]

Fig. 31.4

Sample weaning protocol. Readiness for spontaneous breathing evaluated and patient meets the following criteria: (1) Demonstrates hemodynamic stability. (2) Sedative infusion discontinued. (3) Tube feedings stopped. (4) PaO2/FiO2 > 200; PEEP ≤ 5cmH2O

Sample Ventilator Liberation Pathway

Procedure to be implemented by physician or appropriately certified healthcare professional after eligibility has been determined following collaborative daily assessment by nursing and respiratory therapist. Necessary equipment and personnel confirmed to be available and responsible physician notified.

- 1.

Initiate FiO2 Wean Protocol:

Monitor pulse oximetry (SpO2) during FiO2 weaning (once determined to correlate with arterial blood gas)

Post-intubation, decrease FiO2 by 10–20 % every 30 min till FiO2 < 0.5 while SpO2 > 95 % and/or PaO2 > 75 mmHg

At target SpO2, obtain ABG to confirm adequate oxygen saturation

PEEP may be increased (after discussion with the physician) to ensure FiO2 ≤ 0.7

- 2.

Daily Assessment for Eligibility for Liberation:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Respiratory therapist screens all ventilated patients daily by asking these questions between 5:00–7:00 am. Assessment performed on all post-operative/post-procedure patients as needed upon awakening from sedation.

Response must be “yes” for ‘a – c’; or “yes” for ‘a – d’ in the presence of neuromuscular disease.

- (a)

PaO2 ≥ 60 mmHg on FIO2 ≤ 0.5, PEEP ≤ 7.5, SpO2 ≥ 88 %

- (b)

Hemodynamically stable, absence of vasoactive support except for Dopamine/Dobutamine ≤5 mcg/kg/min or norepinephrine ≤2 mcg/kg/min

- (c)

Patient triggers ventilator spontaneously

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

- (a)