Weakness

Andy Jagoda

Patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with a complaint of weakness pose a challenge because the complaint is often nonspecific and the differential diagnosis is large. Successful ED management depends on a systematic evaluation. Specific attention to potentially life-threatening etiologies is the principal focus, and diligence in data gathering is essential to the establishment of a diagnosis. A detailed history and physical examination guide the selection of appropriate diagnostic studies. Though rarely encountered, when approaching the patient with a complaint of weakness, consideration is given to disorders such as toxic exposures, metabolic abnormalities, botulism, myasthenia gravis, and Guillain–Barré syndrome because of their associated high morbidity and mortality. The emergency physician should consider these and all other disorders that can precipitously compromise the respiratory and functional status of the patient when approaching a patient with the chief complaint of weakness.

The complaint of “dizziness” may accompany that of “weakness,” and, at times, patients use these terms interchangeably. There is considerable overlap in their etiologies. In the ambulatory care setting, dizziness is the most common presenting complaint in patients older than 75 years (1). Weakness is defined as a decrease in muscle strength or power. It may be a focal symptom, involving a single muscle group, or it may be generalized. Dizziness is imprecisely interpreted by patients and may be used to describe lightheadedness, disequilibrium, disorientation, confusion, or vertigo (see Chapters 14 and 70). The emergency physician must appreciate the distinction between these symptoms and attempt to understand the patient’s intended meaning. This chapter specifically addresses those patients who present with a complaint of “weakness.”

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The historical features that are important when assessing the patient with weakness are the acuity of onset and duration of symptoms, exacerbating and mitigating factors, presence of associated symptoms, and location is the weakness, focal or generalized (2). Sudden onset of weakness may suggest a metabolic derangement or infection: A slower progression of symptoms from days to weeks may suggest Guillain–Barré syndrome or myasthenia gravis, although these illnesses may also have accelerated courses. A history of symmetric ascending weakness in a patient with a recent respiratory illness or influenza vaccine will aid in the diagnosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome. The weakness of myasthenia gravis may fluctuate, and a careful history is needed to elicit a progression of symptoms throughout the day or an association with exercise or repeated activity, such as chewing or combing one’s hair. Recent illness, other medical problems, recent vaccination, occupational history, travel history, history of tick bites, use of medications, and use of recreational drugs are important factors in assessing the patient complaining of weakness. A thorough review of systems includes inquiry about recent weight loss, fever or sweats, visual changes (including diplopia), difficulty swallowing, joint or muscle pain, palpitations, change in bowel habits, and skin rashes. Occupational or recreational exposures may indicate drug toxicity.

The patient’s age is an important consideration in developing the differential diagnosis in a patient with weakness. The elderly have a higher incidence of comorbid medical conditions than their younger counterparts. The elderly are also at higher risk of acute central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular events. They are more likely to present with occult infections and metabolic disorders that are symptomatically manifested as weakness (1). In the pediatric age group, infantile botulism and intussusception are two rare but important considerations. Infantile botulism may be seen in children days old to more than 1 year of age. This variant of botulism is much more common than food-borne or wound botulism; it presents with weakness, poor tone, poor suck, or constipation.

The physical examination in a patient complaining of weakness includes a full set of vital signs, orthostatic monitoring, oxygen saturation, and a finger blood glucose. Supplemental oxygen is indicated if hypoxemia is present; the airway must be secured if there is a potential for imminent compromise. Tachycardia, with or without hypotension, suggests volume depletion or toxic drug ingestion. Rectal temperature measurement is particularly important, because infection frequently presents with nonspecific complaints, such as weakness. A blood glucose level should be obtained early during the evaluation, as hypoglycemia may present with an array of symptoms, including weakness. The ears, sinuses, thyroid, and cardiac status should be assessed, as well as a careful evaluation for signs of trauma, which may suggest physical abuse. A rectal examination, including a guaiac test for occult blood, is recommended in select cases.

The neurologic examination begins early in the course of the patient’s evaluation with an assessment of the mental status, for example, assessment of orientation and attention. Altered mental status, including confusion, slowness, or agitation, may represent underlying disease or toxic exposure such as in carbon monoxide poisoning and organophosphate exposure. Suspicion of cognitive defects may prompt a formal mental status evaluation depending on the clinical setting (3). Abnormal neuropsychiatric testing in a patient with carbon monoxide poisoning may indicate the need for hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Cranial nerve testing in the patient with a complaint of weakness focuses on the motor examination. Ptosis can be an early sign of myasthenia gravis, in which case it is usually symmetric (4). When myasthenia is a consideration, having the patient hold an upward gaze for several minutes is helpful in assessing for fatigue. Difficulty with accommodation can be the earliest sign of weakness due to botulism and does not occur with myasthenia. Diplopia due to weak oculomotor muscles should be assessed, with an emphasis on the evaluation of the sixth cranial nerve. The abducens is the longest intracranial cranial nerve and the most sensitive to toxins such as botulism or to increased pressure from intracranial mass lesions.

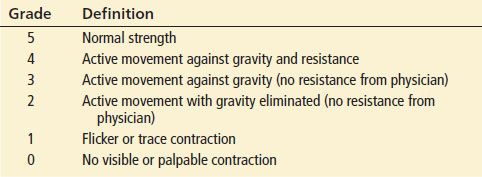

The remainder of the neurologic examination in the patient complaining of weakness concentrates on motor strength, deep tendon reflexes, and assessment for muscle atrophy and fasciculations. Table 13.1 lists the motor strength grading system (from 0 to 5), which permits standardization of documentation of the motor examination among examiners. Deep tendon reflexes are graded on a scale from 0, indicating areflexia, to 4, signifying hyperreflexia, with 2 being normal. Upper motor neuron diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, will typically present with hyperactive reflexes in comparison to the diminished or absent reflexes seen in diseases of the lower motor neuron, as in Guillain–Barré syndrome. Acute spinal cord lesions, such as in a conus medullaris lesion or transverse myelitis, can often initially present with areflexia early in its course. Cauda equina syndrome is due to impingement of the lumbar and sacral nerve roots, commonly from a ruptured vertebral disk. These patients will present with distal motor weakness, areflexia, urinary retention, and anesthesia in the saddle distribution.

TABLE 13.1

Motor Strength Grading System (Medical Research Council Scale)

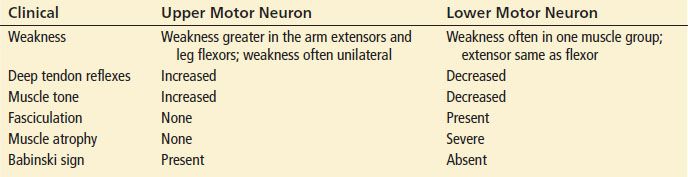

Both upper and lower motor neuron diseases can initially present with the complaint of weakness. The important distinguishing characteristics are listed in Table 13.2. Upper motor neurons arise in the cerebral cortex, and their axons extend through the subcortical white matter, internal capsule, brainstem, and spinal cord, where they synapse directly with lower motor neurons or interneurons, fine-tuning motor activity. Lower motor neuron cell bodies lie in the brainstem motor nuclei and anterior horn of the spinal cord. Their axons extend to the skeletal muscles they innervate.

TABLE 13.2

Upper Versus Lower Motor Neuron Weakness

The weakness of upper motor neuron disease is generally unilateral, the Babinski sign is present, muscle tone is increased, deep tendon reflexes are increased, and no fasciculations are visible or palpable. In general, distal muscle groups are more severely affected than are proximal groups. Lower motor neuron disease affects single muscle groups. Flexors and extensors are equally compromised in an extremity. Deep tendon reflexes and muscle tone are decreased with lower motor neuron disease. Muscle atrophy and fasciculation are long-term results of lower motor neuron lesions.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a combined upper and lower motor neuron disease that can clinically present as a mixed picture. The etiology of ALS is unclear but it is a disease involving the destruction of the anterior horn cells in the spinal column and the Betz cells in the motor cortex of the CNS. The clinical presentation is of asymmetric weakness in the distal motor groups with sensory sparing. Patients often have muscle fasciculations of lower motor neuron disease but associated positive Babinski signs and hyperreflexia as seen in upper motor neuron disorders.

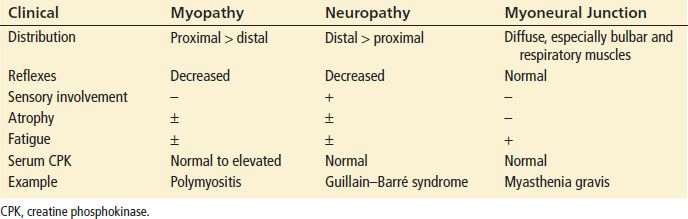

Lower motor neuron diseases can arise from a muscle-based disorder, a neuropathic-based disorder, or a myoneural junction source. Table 13.3 illustrates several symptoms, physical signs, and laboratory findings that distinguish the etiologies of lower motor neuron weakness. Weakness due to a myopathy tends to involve proximal muscle groups, whereas neuropathic disease (Guillain–Barré syndrome) affects distal muscle groups. Myoneural junction diseases have a more distal distribution and are particularly inclined to affect respiratory and bulbar muscle groups (myasthenia gravis and botulism).

TABLE 13.3

Myopathy Versus Neuropathy Versus Myoneural Junction Disease

Spinal cord disorders from compressive or traumatic injury can also present with weakness involving motor function distal to the defect, as well as sensory and autonomic nerve dysfunction. In comparison to atraumatic cord disorders, such as in multiple sclerosis, traumatic cord lesions generally present acutely with distinct sensory and motor findings, as seen with the saddle anesthesia in patients with cauda equina syndrome. Autonomic dysfunction is also seen more commonly in spinal cord injuries manifesting with hypotension or priapism. Detailed history (including anticoagulation, recent fall or trauma, immune status, fever, intravenous drug abuse, spinal procedure, or surgery) is often necessary to make the diagnosis. An uncommon and occasionally overlooked diagnosis of spinal epidural abscess can be made in the setting of a patient with a history of intravenous drug abuse presenting with severe back pain, fever, and progressive lower extremity weakness.

When psychogenic weakness is considered in the differential diagnosis, several maneuvers may be helpful. Weak muscles give way to pressure in a smooth fashion, but psychogenic weakness usually results in a jerking or sudden release. In a patient with upper extremity weakness from organic disease, making a fist should not result in wrist extension (unless there is an isolated lesion of the flexor tendons); in functional states, the wrist extends as the patient tries to make a fist. In patients with psychogenic bilateral lower extremity weakness, attempts to lift one leg against resistance result in the other leg firmly thrusting downward, whereas in patients with organic disease, the downward thrust is diminished or absent.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of the weak patient is extensive. Division of the etiologies into broad categories, such as metabolic, toxic, infectious, structural, endocrinologic, cardiac, and rheumatologic, permits a more organized approach to this extensive list. In this section, the diagnoses are also presented in order from high risk to low risk. Detailed history taking and careful examination should direct the physician to one of these categories. Diagnostic testing may then be used to narrow the differential diagnosis and determine the management plan for the patient’s condition.

Metabolic

Metabolic derangements that can present with weakness include hypoxia, hyperthermia, and alterations in serum glucose, potassium, sodium, phosphate, magnesium, and calcium (5). Severe hypokalemia presents with generalized weakness and paralysis due to a dysfunction of potassium regulation (6). This state may be induced by medications such as diuretics as well as gastrointestinal losses; it also rarely occurs in association with genetic disorders such as familial periodic paralysis. Hyperkalemia, though typically known for its effects on the myocardium, is a lesser known cause of weakness presenting with ascending paralysis, ultimately leading to respiratory failure (6). One of the most frequently seen causes of weakness in the ED is hypoglycemia, which accounts for an average of 380,000 ED visits per year in the United States (7). During the summer, elderly patients with heat exhaustion will frequently present to the ED with weakness due to dehydration and inability to regulate their temperature.

Cardiovascular

Weakness may be the only complaint in the elderly patient with acute myocardial infarction (MI); this must be in the differential diagnosis for all geriatric patients presenting with nonspecific complaints. In one study of symptoms of MI in the elderly with autopsy-proven MI, 20% of the patients initially presented with weakness (8). As the population ages, more patients will present with atypical complaints of MI such as weakness or shortness of breath.

Myocarditis is another serious but often missed cause of weakness in a patient with a recent viral infection. Patients complain of weakness as part of a constellation of symptoms that includes cough, dyspnea, myalgias, fever, vomiting, or diarrhea. In one study, up to 60% of patients with myocarditis did not have chest pain (9).

Other cardiovascular causes of weakness associated with lightheadedness or presyncope are due to transient decreased cerebral perfusion. These disorders include postural hypotension, carotid and vertebral artery insufficiency, cardiac dysrhythmias, vasovagal events, and states of decreased cardiac output.

Central Nervous System Lesions

Structural lesions in the CNS generally present with focal weakness. Weakness, in association with changes in speech, visual loss, diplopia, paresthesias, and dizziness, are frequently associated with the diagnosis of stroke (10). Patients with brainstem infarcts can present with difficulty swallowing, talking, or breathing, in addition to weakness. Lesions in the frontal lobes, basal ganglia, and cerebellum can cause disequilibrium.

Lesions in the spinal canal such as epidural hematoma and abscess and metastatic cancer can result in weakness that is symmetric and distal to the site of compromise. Transverse myelitis is an infrequent yet debilitating demyelinating disease of the spinal cord presenting with an acute onset of back pain, lower extremity weakness or paralysis, and sensory deficit below the level of involvement. The etiology is unknown but thought to be related to a recent viral infection or autoimmune disorder. The clinician should suspect this disease in a patient with a recent viral illness presenting with both weakness and sensory deficit below a cord level. This disease should not be confused with Guillain–Barré syndrome. Though also preceded by a viral syndrome, the physical examination findings of Guillain–Barré syndrome will typically demonstrate sparing of the anal sphincter and hyporeflexia with progressive weakness in an ascending pattern over days to a week. Clinical findings of transverse myelitis generally progress over 24 hours and include diminished or absence of strength and sensation below the level of involvement, sphincter dysfunction, hyperreflexia, and urinary incontinence or retention.

Specific Neuromuscular Diseases

The patient with myasthenia gravis will present with weakness of a specific muscle group associated with blurred vision, diplopia, and ptosis. Patients with Guillain–Barré present with generalized ascending paralysis with variable sensory deficits. ALS is a disease that affects both upper and lower motor neurons and can present with a mixed picture. Myopathies caused by metabolic derangements, medications, and inflammatory states may present with symmetric proximal muscle weakness with preservation of sensory function.

Infections

All infections can potentially cause weakness, either through nonspecific mechanisms, such as those seen with mononucleosis or hepatitis, or from specific toxins affecting neuromuscular function, such as poliomyelitis, botulism, Guillain–Barré, or tick paralysis. Sinus and ear infections can affect the labyrinthine system and produce lightheadedness or vertigo. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can directly or indirectly cause the full spectrum of weakness, from nonspecific fatigue to neuropathies and myelopathies. Chronic fatigue syndrome, thought to be viral in origin, requires an extensive workup to exclude all other processes before the diagnosis can be established. This diagnosis should not be made in the ED.

Medications and Toxins

Prescription mediations can produce generalized weakness (Table 13.4). There are usually no focal findings on examination. In one study of 106 patients with a chief complaint of weakness and dizziness, 9% of all patients and 20% of those older than age 60 had symptoms attributed to prescription medications (1). Drugs associated with vasodilatation, bradycardia, or diuresis can produce orthostatic blood pressure changes, often giving the patient the feeling of weakness.

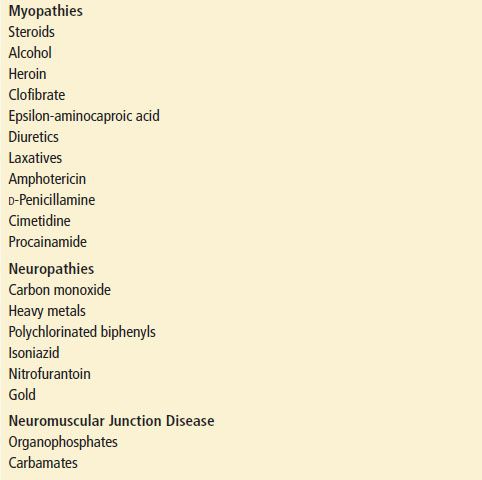

TABLE 13.4

Commonly Used Drugs and Other Substances Associated with Weakness