96 Vertigo

• The majority of cases of vertigo arise from a peripheral source (e.g., cranial nerve VIII, vestibular structures) rather than a central source.

• The Dix-Hallpike test (also called the Nylan-Bárány test) can help confirm the diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

• Other causes should always be considered because the signs and symptoms of central vertigo can mimic those of peripheral vertigo.

• Central vertigo should be suspected in patients with any abnormal neurologic findings.

Peripheral Vertigo

Epidemiology

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

The most common type of vertigo is benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).1 It occurs in all age groups but becomes more common with aging. Women are affected twice as often as men.

Pathophysiology

Nystagmus is an involuntary rhythmic movement of the eyes to and fro that is often seen in patients with vertigo. Nystagmus is defined in terms of the direction of the fast-phase component. The factors listed in Table 96.1 should be noted in all patients with nystagmus. It should be kept in mind that on extremes of lateral gaze, several-beat nystagmus is a normal finding in 60% of patients.

Table 96.1 Characteristics of Nystagmus

| Direction | Left or right |

|---|---|

| Axis | Upbeat or downbeat |

| Nature | Rotary/torsional or vertical |

| Duration | Seconds, minutes, or persistent |

| Associated Factors | Spontaneous or positionalEffect of visual fixation |

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

BPPV results from a mechanical defect in the inner ear. Canalolithiasis is the most accepted hypothesis. According to this premise, the culprits are free-floating otoliths that have become displaced from the utricle and inappropriately enter and activate the end-organs of the semicircular canals.2 With certain head movements, a clump of otoliths moves, causes the endolymph to move with resultant inappropriate displacement of the cupula. Movement of the cupula triggers neural firing, with consequential vertigo and nystagmus. Less commonly, otoliths can adhere to the cupula and result in vertigo. This mechanism is called cupulolithiasis.

Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis

See Table 96.2 for the pathophysiology of other causes of peripheral vertigo.

Table 96.2 Pathophysiology of Various Causes of Peripheral Vertigo

| CAUSE | PATHOPHYSIOLOGY |

|---|---|

| BPPV | Otoliths inappropriately displaced into the semicircular canals |

| VN/L | Inflammation of the vestibular nerve |

| Meniere disease | Excessive endolymph in the vestibule |

| Posttraumatic vertigo | Trauma to the occiput or temporal area |

| Perilymph fistula | Abnormal opening between the middle and inner ear |

| Acoustic neuroma | Slowly expanding tumor compressing cranial nerve VIII |

BPPV, Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; VN/L, vestibular neuritis/labyrinthitis.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Details of the patient’s history, as well as findings on physical examination, can help narrow the differential diagnosis (Box 96.1).

Box 96.1 Evaluation of Vertiginous Patients

Consider the following factors when questioning patients during emergency department evaluation:

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

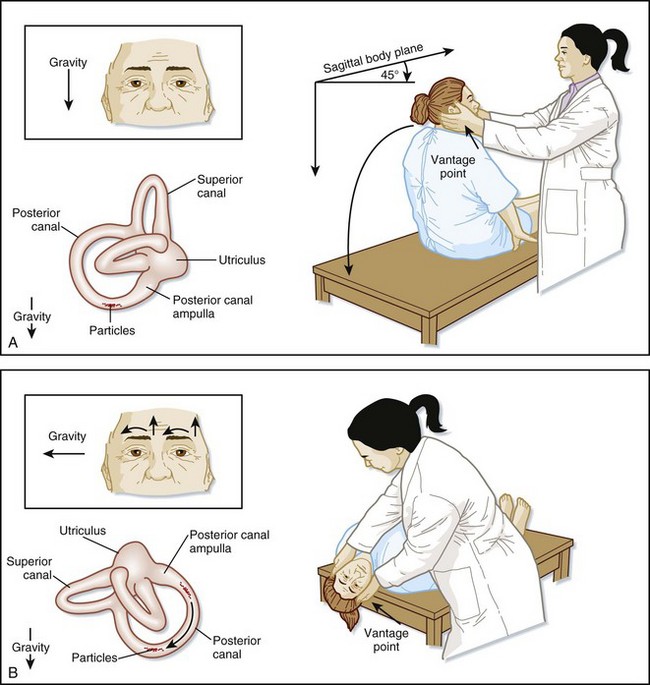

The diagnosis of BPPV is confirmed with the Dix-Hallpike test,3 also called the Nylan-Bárány test (Fig. 96.1; Box 96.2).

Box 96.2 Findings on the Dix-Hallpike Test in Patients with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

Latency is approximately 3 to 10 seconds.

Significant subjective vertigo is present.

The intensity of vertigo escalates and then slowly resolves.

Vertigo and nystagmus last for approximately 5 to 30 seconds.

The nystagmus is upbeat (toward the forehead) and torsional toward the abnormal ear.

The nystagmus often reverses direction when the patient returns to the seated position.

Fatigability—the vertigo and nystagmus decrease and eventually subside with repeated positioning.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree