110 Vasculitis Syndromes

• A patient’s combined genetic predisposition and regulatory mechanisms control expression of the immune response to antigens.

• Negative test results for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies do not exclude disease, nor do positive results indicate a specific syndrome.

• The combination of clinical, laboratory, biopsy, and radiographic findings usually points to a specific vasculitis syndrome.

• Definitive diagnosis of a vasculitic syndrome depends on demonstration of vascular involvement and may be accomplished by biopsy or angiography.

• Differentiation of primary and secondary vasculitis is essential because their pathophysiologic, prognostic, and therapeutic aspects differ.

• The diagnosis of vasculitis should be considered in any patient with febrile illness and organ ischemia without other explanation.

Epidemiology

In 1994, the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference named and defined the 10 most common forms of vasculitis according to vessel size (Box 110.1). This system is based on the fact that different forms of vasculitis attack different vessels.1,2 These criteria were established to differentiate specific types of vasculitis, but they are often used as diagnostic criteria. The vasculitic syndromes feature a great deal of heterogeneity and overlap, which leads to difficulty with regard to categorization.3 In addition, many patients display incomplete manifestations, thereby adding to the confusion. Emergency physicians should keep in mind the fact that nature does not always follow the patterns and artificial boundaries drawn by classification systems.4

Box 110.1

Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Classification of Primary Vasculitides

From Kallenberg CG. Vasculitis: clinical approach, pathophysiology, and treatment. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2000;112:656–9.

Takayasu Arteritis

Takayasu arteritis (also referred to as aortic arch syndrome) is a granulomatous large vessel vasculitis that primarily affects the aorta, its branches, and the pulmonary and coronary arteries.1 This rare disease predominantly affects women in the 20- to 30-year-old age group and is more common in Asian and South American women. Mortality ranges from 10% to 75%.

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a multisystem necrotizing vasculitis of small- and medium-sized muscular arteries. Visceral and renal artery involvement is characteristic.3 The mean age at onset is 50 years, although it can occur at any age. Men, women, and racial groups are all affected equally. This rare disease affects fewer than 10 per 1 million persons worldwide.

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease, also referred to as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, primarily affects children younger than 5 years. This acute systemic vasculitis is a febrile multisystem disease that is the leading cause of acquired heart disease in children in the United States.1 The disease occurs worldwide but predominates in Japan, Asia, and the United States.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome is a rare small vessel vasculitis manifested by fever, asthma, and hypereosinophilia.1 This disease is also referred to as allergic angiitis and granulomatosis, particularly when it affects the lungs. It is estimated that about 3 million people are affected worldwide, with an equal incidence between sexes. It is seen at all ages with a mean onset at 44 years of age.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (anaphylactoid purpura) is a small vessel vasculitis that predominantly affects children and is characterized by palpable purpura, arthralgia, glomerulonephritis, and gastrointestinal symptoms.3 Though also seen in adults, 75% of cases occur in children younger than 8 years. It is more common than other vasculitides and affects males more frequently than females in a 2 : 1 ratio. It has a peak incidence in winter and spring and usually follows an upper respiratory tract infection.

Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

This disorder, also called hypersensitivity vasculitis or predominantly cutaneous vasculitis, involves small vessels of the skin and is the most common vasculitic manifestation seen in clinical practice.1 It has an incidence of 15 per million.4 In about 70% of cases, cutaneous vasculitis occurs along with an underlying process such as infection, malignancy, medication exposure, and connective tissue disease or as a secondary manifestation of a primary systemic vasculitis.

Behçet Syndrome

Behçet syndrome is a multisystem inflammatory disease that affects vessels of all size.1 It is manifested as recurrent aphthous oral and genital ulcerations along with ocular involvement. Behçet syndrome is most prevalent at ages 20 to 35 years, with males suffering more severe disease.

Pathophysiology

Vasculitis, also known as the vasculitides or the vasculitis syndromes, is a clinicopathologic process that results in inflammation and damage to blood vessels.3 Cell infiltration with inflammatory modulators causes swelling and changes in function of the vessel walls. This compromises vessel patency and integrity and leads to tissue ischemia, necrosis, and bleeding. Because most forms of vasculitis are not restricted to a certain vessel type or organ, the syndromes are broad and heterogeneous. Vasculitis is a systemic multiorgan disease, so the findings may be dominated by a single or a few clinical organ manifestations.4

Management of patients with the secondary forms of vasculitis needs to be directed toward the underlying disease process. The primary vasculitides, once thought to be uncommon, have proved to be much less rare than previously estimated, and awareness of the incidence and prevalence of all forms of vasculitis has recently increased.5 This chapter focuses on the primary or de novo vasculitides.

The pathophysiology of the vasculitis syndromes remains poorly understood, with variation between disease states contributing to the difficulty. It is also not clear why vasculitis develops in certain patients in response to antigenic stimuli and not in others; however, in each disease state, immunologic mechanisms play an active role in mediating blood vessel inflammation.1 Blood vessels can be damaged by three potential mechanisms (Box 110.2).6

Box 110.2

Three Potential Mechanisms of Blood Vessel Damage in Vasculitis with Corresponding Diseases

From Fauci AS, Sneller MC. Pathogenesis of vasculitis syndromes. Med Clin North Am 1997;81:221–42.

Two main factors are involved in the expression of a vasculitic syndrome: genetic predisposition and regulatory mechanisms associated with the immune response to antigens. Only certain types of immune complexes cause vasculitis, and the process may be selective for only certain vessel types. Other factors are also involved—for example, the reticuloendothelial system’s ability to clear the immune complex, the size and properties of the complex, blood flow turbulence, intravascular hydrostatic pressure, and the preexisting integrity of the vessel endothelium.3

Temporal (Giant Cell) Arteritis

Giant cell arteritis is a panarteritis characterized by inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltrates and giant cell formation in vessel walls. The intima proliferates and the internal elastic lamina fragments. Organ pathology results from ischemia related to the involved vessel derangement.3

Takayasu Arteritis

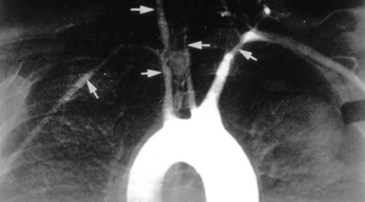

The inflammation in Takayasu arteritis involves all vessel wall layers of medium- and large-sized vessels, especially the aorta and its branches. Panarteritis with inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltrates and giant cells predominates. This results in scarring and fibrosis with disruption and degeneration of the elastic lamina. Narrowing of the vessel lumen (Fig. 110.1) follows with frequent thrombosis.3 Vessel dilation and the formation of aneurysms may also occur. Organ pathology results from ischemia.

Polyarteritis Nodosa

The inflammatory lesions associated with polyarteritis nodosa are segmental and involve the bifurcations and branches of arteries. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils infiltrate all layers of the vessel wall. The resultant intimal proliferation and degeneration of the vessel wall lead to vascular necrosis, which in turn results in thrombosis, compromised blood flow, and infarction of the involved tissues and organs. Characteristic aneurysmal dilations of up to 1 cm are common. Multiple organ systems are involved.3

Kawasaki Disease

The etiology of Kawasaki disease is unknown, but increasing evidence supports an infectious cause; however, whether the inflammatory response results from a conventional antigen or a superantigen continues to be debated. Although a strong predilection for the coronary arteries is seen, this vasculitis is systemic and may involve medium-sized arteries with corresponding manifestations. Initially, neutrophils are present in great numbers, but the infiltrate rapidly switches to mononuclear cells, T lymphocytes, and immunoglobulin A (IgA)-producing plasma cells. Inflammation involves all three layers of vessels. As in other vasculitides, there is typical intimal proliferation and infiltration of the vessel wall with mononuclear cells, which leads to beadlike aneurysms and thrombosis. Cardiomegaly, pericarditis, myocarditis, myocardial ischemia, and infarction may result.3