INTRODUCTION

FREE-LIVING AMEBA INFECTION

Free-living amebas, usually harmless protozoan residents of soil and water, can cause three distinct, occasionally devastating, human illnesses. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is a disease of the previously healthy and is caused by Naegleria fowleri. Granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE) is caused by Acanthamoeba species or Balamuthia mandrillaris, and occurs in both healthy and immunocompromised persons. In wealthier countries, contact lens users may suffer from chronic amebic keratitis, also caused by Acanthamoeba. While these diseases are found worldwide, they are more common in tropical and subtropical regions.

PAM is devastating, usually fatal, and found mostly in children or young adults with a history of recent freshwater exposure. The organism enters through the nose and penetrates the cribriform plate to the subarachnoid space and brain. The acute illness is indistinguishable from bacterial meningitis. Patients with GAE often present with an initial focus of infection in the skin or respiratory tract followed by neurologic changes reflective of extensive brain involvement.

The mainstay of management is consideration of these uncommon diseases. PAM is almost always fatal, but one survivor was successfully treated with amphotericin B, miconazole, and rifampin. Isolated cutaneous disease from Acanthamoeba and B mandrillaris can be cured, but brain involvement is fatal and often diagnosed at autopsy. Patients with suspected amebic keratitis should have immediate ophthalmologic referral.

Lack of response to usual antimicrobials in a patient with severe meningitis symptoms should lead to the suspicion of PAM, particularly with recent freshwater exposure.

Global warming might increase the rate of N fowleri infection as the organism thrives in freshwater over 30°C.

Fatal cases of PAM have been reported following tap water nasal irrigation using a “neti pot” (a device used to clean nasal passages). Use of sterile or previously boiled water when irrigating eliminates the risk.

Consider Acanthamoeba infection in all contact lens wearers with a corneal infection. Early amebic keratitis can mimic the dendritic pattern of herpes simplex infection.

Immunocompromised patients with space-occupying lesions should have GAE on the differential.

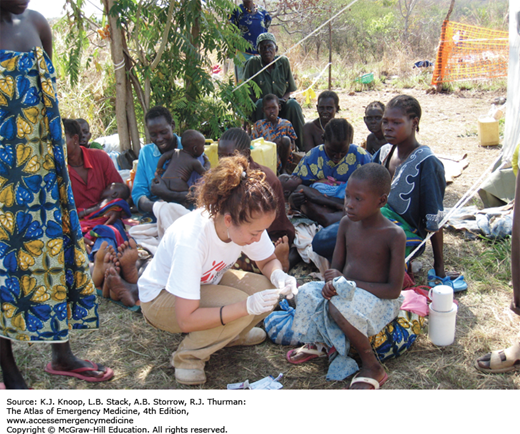

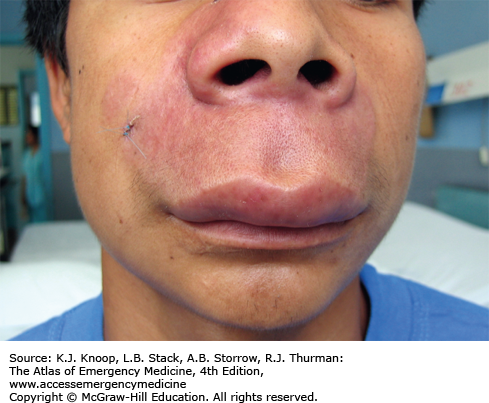

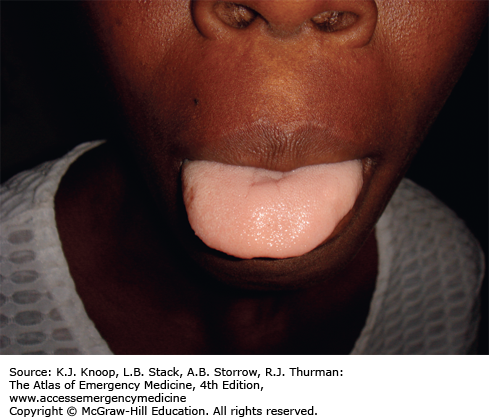

FIGURE 21.1

Ameba. Twenty-one-year-old patient from South America with 1 year of symptoms from Balamuthia mandrillaris. The primary site often involves the mid-face and oral cavity. This patient did not have intracranial involvement. (Photo contributors: Seth W. Wright, MD, and Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.)

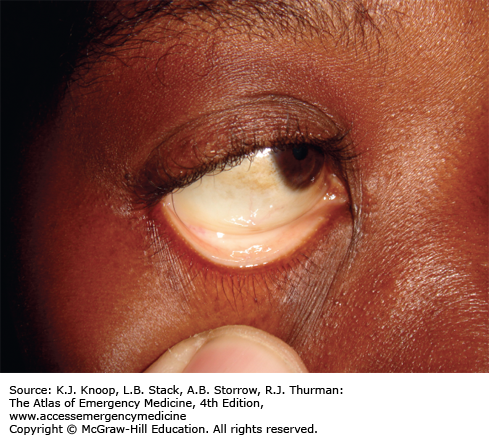

ANEMIA IN THE TROPICS

Anemia in the tropics is a common medical condition resulting from various nutritional deficiencies, infections, parasites, and inherited disorders. Its prevalence and causes differ significantly from developed countries, and is often multifactorial.

Overall, iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia worldwide. Similar to deficiencies of folic acid and vitamin B12, it results from diets rich in carbohydrates, but poor in meats, proteins, and vegetables. Most patients with AIDS in developing countries are anemic, with more severe cases seen in those coinfected with tuberculosis. Malaria causes hemolysis and hypersplenism, and should always be considered in anemic patients. Hookworm infection is another common cause of anemia, particularly in children and pregnant women. Other parasitic illnesses causing anemia include visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) and African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). Hemoglobinopathies, including sickle cell anemia and thalassemia, are common in Africa, the Middle East, the Americas, and South Asia. Severe hemolytic anemia can occur in patients with G6PD deficiency.

Treatment depends on the suspected cause(s). Iron and folate supplementation can lead to a rapid and dramatic increase in red cell counts in patients with nutritional deficiencies. A low threshold for malaria diagnosis and treatment is important. Empiric treatment for hookworm is advisable. Red blood cell transfusion is rarely needed in stable patients, even those with extremely low counts.

Administration of the antimalarial agent primaquine to patients with G6PD deficiency can lead to fatal hemolysis.

Thrombocytopenia in conjunction with anemia is highly suggestive of malaria in endemic areas.

Anemia in pregnancy should be screened for and aggressively treated as this improves both maternal and fetal outcomes.

ANTHRAX

Anthrax, a worldwide zoonotic infection caused by Bacillus anthracis, was the first definitively recognized bacterial pathogen in human history. Most cases are sporadic, although occasional large outbreaks have been reported in Africa. Control of the disease in livestock has made endemic anthrax uncommon in developed countries, but it has taken on increased importance due to its use as a bioterrorism agent.

Cutaneous anthrax is the most common form, accounting for 95%. Infection occurs after spore exposure, with the initial manifestation of a small, painless, pruritic papule. The papule develops a large, central vesicle, followed by the classic necrotic ulcer with a black, depressed eschar. Local edema, regional lymphadenopathy, and systemic symptoms can occur. About 20% will progress to systemic bacteremia. Inhalational anthrax occurs after aerosolized spore exposure, and typically follows a biphasic course: (1) nonspecific upper respiratory infection–like symptoms and (2) then, in 1 to 4 days, fulminant bacteremia with fever, respiratory distress, hemorrhagic mediastinitis, and shock. Gastrointestinal (GI) anthrax is rare, affects the oropharynx or alimentary tract, and occurs after contaminated meat ingestion. It causes a nonspecific gastroenteritis, necrotic GI tract ulcers, and may progress to shock or death 2 to 5 days after symptom onset.

Uncomplicated endemic cutaneous anthrax is typically treated with oral or intramuscular penicillin. Doxycycline, erythromycin, and ciprofloxacin are alternatives. High-dose intravenous (IV) penicillin is used in cutaneous disease with systemic findings, and for inhalational or GI disease.

Patients with suspected bioterrorism-related anthrax require hospital admission with immediate public health notification. They should be decontaminated with removal (and sealed storage) of all clothing and cleansing with soap and water. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend ciprofloxacin or doxycycline as first-line therapy. Inhalational and other severe forms are treated with additional multidrug antimicrobial therapy. Glucocorticoid therapy is controversial, but might be beneficial in meningitis or cutaneous disease with extensive head and neck edema.

All forms can progress to hemorrhagic meningitis, which can mimic a traumatic tap on lumbar puncture.

Cutaneous and inhalational anthrax have been reported from use of imported animal hide drums.

Injection anthrax is rare and recently found among heroin users in Great Britain and Germany. Symptoms include abscess, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, and sepsis.

The length of antibiotic therapy is usually 7 to 10 days, but postexposure prophylaxis involves 60 days, including vaccine administration.

The classic pathologic finding of inhalational anthrax is hemorrhagic mediastinitis, demonstrated as a widened mediastinum on chest radiography.

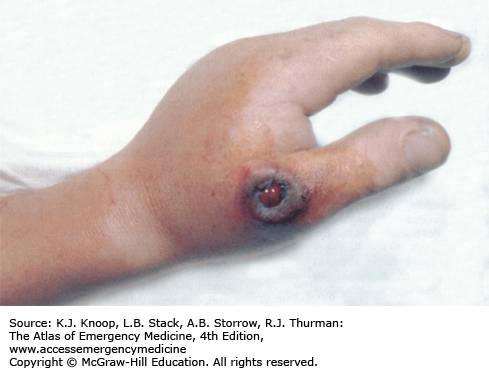

FIGURE 21.6

Anthrax. A black eschar with a central hemorrhagic ulceration on the thumb associated with massive edema on the hand. (Used with permission from Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005: p. 631.)

FIGURE 21.7

Anthrax Progression. (A) Initial facial cutaneous anthrax with early lesion development and massive facial edema. (B) Interval development of septicemia. The lesion is developing a more typical dark coloration. (C) The patient following resolution of sepsis. (Photo contributor: Seth W. Wright, MD.)

ASCARIASIS

Ascaris lumbricoides is the most common human intestinal roundworm infection. The parasites are found worldwide and are highly endemic where sanitation and hygiene are poor; they commonly cause infection in regions where human feces are used as fertilizer. Adult worms live in the small intestine and produce enormous numbers of eggs, which are excreted in the feces. Passed eggs require at least several weeks in warm, moist soil before embryonating into an infective egg. Ingested eggs hatch in the jejunum, migrate through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream, and are transported to the lungs. Larval worms burrow through the alveolar walls, ascend up through the trachea, and are swallowed back into the small intestine where they develop into adults.

Most infections are asymptomatic. Patients may present for care if they pass a worm in their stool. A heavy worm burden may lead to abdominal pain, pancreatic/biliary disease, or intestinal obstruction. Failure to thrive and decreased cognitive development are seen in heavily infected children. Migrating worms may cause biliary obstruction, appendicitis, or liver abscesses.

Diagnosis is from identification of a passed worm or examination of stool for eggs.

Outpatient treatment with mebendazole or albendazole is usually effective but only on worms in the adult intestinal stage. Thus, it is recommended that a stool examination be done at 2 to 3 months and retreatment initiated if positive for eggs.

Marked peripheral eosinophilia can be seen during the migratory stage.

While in the lungs, migrating worms can cause an eosinophilic pneumonitis with asthma-like symptoms, or “Löffler syndrome.”

Ascaris worms occasionally migrate from the anus, mouth, or nose following antihelmintic treatment.

Ascaris is the most common cause of acute abdominal surgical emergencies in some highly endemic countries.

CHAGAS DISEASE

American trypanosomiasis, or Chagas disease, is a zoonotic protozoal infection caused by Trypanosoma cruzi. Chagas is spread by triatomine insects with a large variety of mammals serving as natural reservoirs. Disease is limited to the western hemisphere and is most common in areas of substandard housing as the vector insects proliferate in adobe, unfinished brick walls, and in thatched roofs. Chagas is considered the most important protozoal disease in the Americas, surpassing malaria in morbidity and mortality. It is estimated that 10 million people are infected, including 300,000 immigrants within the United States.

Chagas is usually acquired during childhood and persists for life. Infection occurs when the insect defecates while taking a blood meal and the infectious stool is rubbed into the bite wound or a mucus membrane (often the conjunctiva). Acutely, infection is often asymptomatic but can present with a skin lesion at the infection site (chagoma), fever, adenopathy, myocarditis, and hepatosplenomegaly. The organism can be isolated during the indeterminate phase (years or even lifespan). Chronically, about 30% develop a cardiomyopathy with progressive biventricular heart failure. Severe arrhythmias, including complete heart block, are common. Approximately 10% of patients will develop digestive complications due to loss of lumen wall neurons, including megaesophagus and megacolon.

During acute infection, trypanosomes are seen on the blood smear and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is useful for diagnosis, but serology is typically negative. Serological assays are used to diagnose chronic disease. Blood culture and xenodiagnosis can also be used, but lack sensitivity.

Patients presenting with acute symptoms are treated with benznidazole or nifurtimox. Patients with chronic disease should be worked up with an electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiography, and referred as indicated. Antitrypanosomal treatment is warranted in the indeterminate phase of chronic infection and in those with early stage cardiomyopathies.

Chagas is the most common cause of cardiomyopathy in many Latin American countries. The disease should also be considered in patients with complete heart block or other arrhythmias.

Chagas is surprisingly common in wild and domestic mammals in the Southern and Southwest United States. The prevalence in Tennessee dogs is 6.4%, and is higher in wild animals such as raccoons, skunks, and rodents.

Human infection in the United States is rare since the vector insects are uncommon inside modern housing, but occasional cases have been reported in those without a history of travel.

Universal screening of blood for Chagas is now routine in the United States.

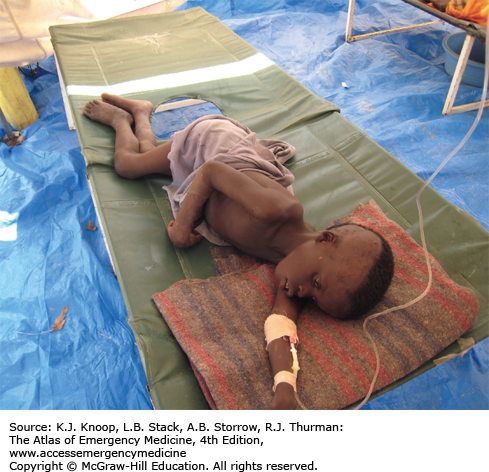

CHOLERA

Cholera is a severe diarrheal disease caused by Vibrio cholerae, a gram-negative bacterium, and is spread via the fecal-oral route. It is associated with poor hygiene and overcrowding, as well as the resultant contamination of food and water. Endemic disease is present in many areas of the world with occasional epidemics. Massive outbreaks in previously disease-free areas can occur following disasters or breakdowns in public health measures, such as seen in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake.

Cholera is characterized by massive, watery, gray, and painless diarrhea. The stool resembles “rice water” without blood or pus. Patients may have associated vomiting. Renal failure, hypotension, and circulatory collapse can occur within hours of diarrhea onset. Mortality rates as high as 20% to 50% among severe cases can be seen if adequate rehydration is not available. Death rates of less than 2% are seen with good case management.

The mainstay of treatment is hydration. Oral rehydration solutions are adequate for mild and moderate dehydration. Patients with severe dehydration are treated with IV lactated Ringer solution and oral rehydration. Per World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, adult patients may require 10 to 15 L in the first 24 hours. Monitoring of electrolytes and renal function is ideal, but often not available in areas struck by cholera epidemics. Hypokalemia is common. Antibiotics are not required for recovery as the illness is self-limiting, but doxycycline may reduce the volume of diarrhea and shorten the duration of illness.

Cholera, plague, and yellow fever are the three diseases internationally notifiable to WHO.

John Snow’s removal of the Broad Street water pump handle during the 1854 cholera epidemic in London is considered to be the beginning of modern field epidemiology.

Rapid cholera test kits are available and are essential for early confirmation of disease in the first suspected cases.

An oral cholera vaccine is available, but only confers short-term immunity and is not available in the United States.

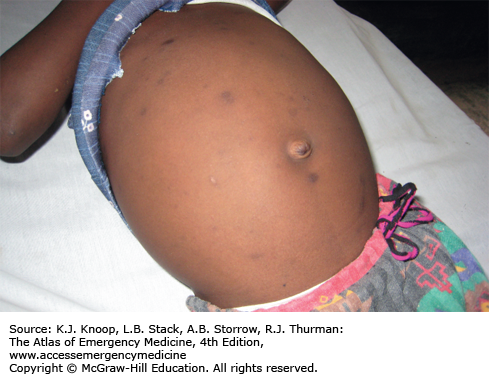

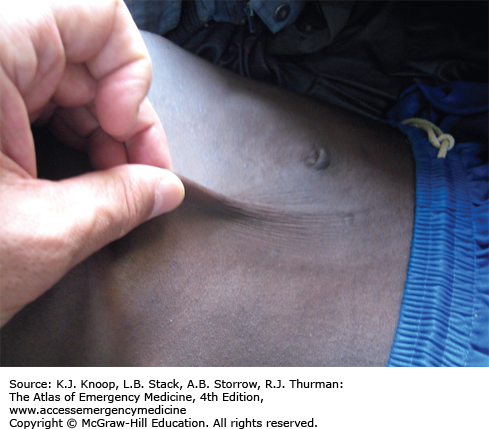

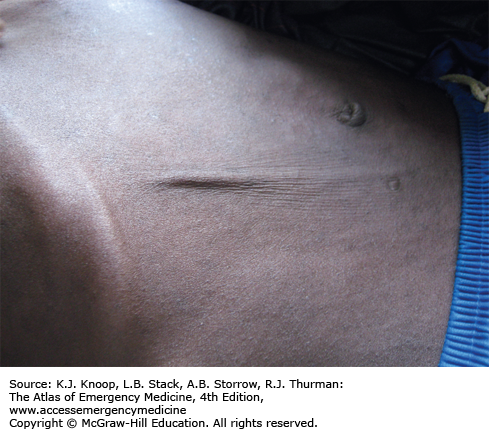

CUTANEOUS LARVA MIGRANS

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM), also known as “creeping eruption,” is the most common dermatologic problem following a trip to the tropics. CLM is a worldwide, parasitic infection commonly seen in warm, tropical environments; it is uncommon in developed countries due to shoe wearing habits and routine deworming of pets.

CLM is most commonly caused by dog and cat hookworms, Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma braziliense; humans are an accidental host. The infected animal passes eggs in its feces where they hatch, molt, and feed on soil bacteria. Upon contact with a human host, the larval worm penetrates the skin and attempts dermal migration. The worm remains under the skin since it lacks collagenase and cannot penetrate deeper layers. The larvae are unable to complete their life cycle, and, if left untreated, are trapped in the epidermis and will die in 2 to 8 weeks.

CLM is commonly seen on the lower extremities of travelers who walk barefoot on beaches with contaminated sandy soil. Symptoms are manifested by an erythematous tract with a distinctive serpiginous dermal pattern. The tract is markedly pruritic and may feel like a thread on palpation.

Treatment of CLM consists of mebendazole, albendazole, ivermectin, or topical application of thiabendazole. Antipruritics may also help.

The lesions advance a few millimeters to several centimeters daily as the larva migrates.

Excoriation and secondary infections frequently occur. This can make the distinctive wandering rash more difficult to visualize.

Biopsy is usually not helpful for diagnosis since the organism lies 1 to 2 cm away from the leading edge of the eruption.

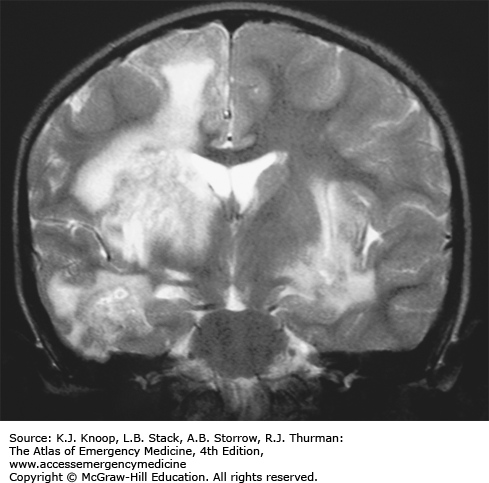

CYSTICERCOSIS

The larval form of the pork tapeworm Taenia solium causes cysticercosis and affects 50 million people worldwide. Disease in developed countries is usually due to immigration or foreign travel. Taeniasis (intestinal tapeworm) is acquired from ingesting cysts from undercooked pork. Eggs passed in the stool from these carriers are highly infectious and may survive in the environment for months. Humans acquire cysticercosis from the ingestion of these eggs/larva, usually through unhygienic food preparation. Once the eggs are consumed, they hatch, penetrate the bowel wall, and travel to the subcutaneous tissue, skeletal muscle, and brain, though they may involve any organ. Two distinct types of diseases exist: neurocysticercosis (which can be parenchymal or extraparenchymal) and extraneural cysticercosis. Symptoms are dependent on the affected organ system; significant morbidity is associated with ocular, cardiac, and neurologic involvement. The larval worm will eventually die and leave calcified lesions.

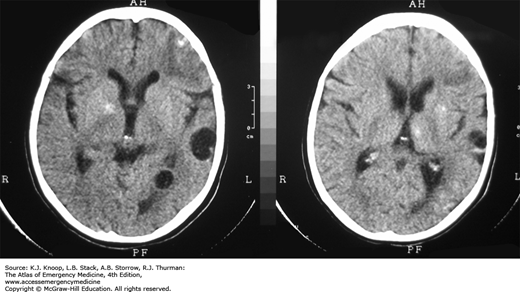

Intestinal taeniasis is diagnosed through egg identification on stool exam or by passage of an intact worm or worm segment. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have facilitated recognition of neurocysticercosis with visualization of a contrast-enhancing ring lesion. Diagnosis may also be made by biopsy, serum, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) antibody testing. Neurocysticercosis should be strongly considered in endemic regions or in immigrants with new onset seizures.

Seizures are treated with standard medications. Calcified lesions do not require specific anticysticercal therapy. Viable cysts can be treated with albendazole or praziquantel, but should be done with expert consultation. Inpatient management is advisable if viable cysts are to be treated as inflammatory reactions may occur. Corticosteroids are recommended in this situation. Surgical intervention may be indicated for obstructing neurologic lesions or intraocular lesions.

Infection is most common in rural areas of developing countries where pigs are allowed to roam freely and ingest infected human feces. This completes the cycle and propagates infection.

Cysticercosis and taeniasis are rare in predominantly Muslim countries where eating pork is uncommon; however, cysticercosis is still possible due to ingestion of contaminated nonpork food products.

The adult tapeworm can attain a length of 20 feet or more, and can live up to 20 years in the intestine.

Most people with an intestinal pork tapeworm do not have cysticercosis.

The only pathognomonic CT or MRI finding of neurocysticercosis is a 2- to 4-mm bright nodule within the cyst (“cyst with dot sign”) that represents a solid larval tapeworm.

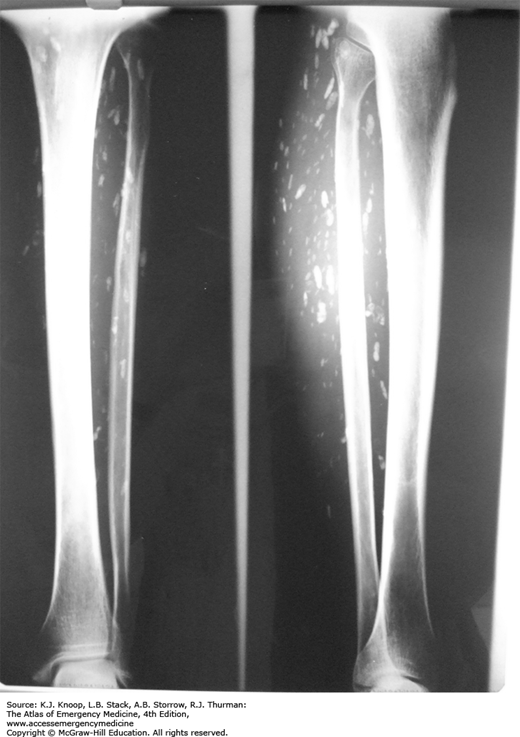

FIGURE 21.19

Cysticercosis Cysts. Multiple calcified soft tissue cysts noted as an incidental finding on a lower leg radiograph in a patient with disseminated cysticercosis. The “cigar-shaped” calcifications are highly suggestive of cysticercosis. (Photo contributors: Seth W. Wright, MD, and Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.)

DENGUE FEVER

Dengue fever, also known as “breakbone fever,” is a mosquito-borne viral disease. A flavivirus, dengue is a rapidly emerging illness due to reintroduction of Aedes species mosquitoes into areas of previous eradication. It is now distributed throughout tropical and subtropical regions, and widespread epidemics have occurred in the Caribbean and Southeast Asia, among other world regions. Dengue is one of the most common causes of fever in returning travelers.

The incubation period is usually 3 to 7 days, with symptom resolution within 10 days. Infection ranges from subclinical symptoms to a hemorrhagic state with possible shock. Most commonly, it is characterized by fever, severe myalgias, retro-orbital pain, and headache. A rash, seen in approximately half, is usually maculopapular, but may be mottled, flushed, or petechial. The recently revised classification of dengue severity consists of dengue without warning signs, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue based upon the degree of plasma leakage, spontaneous bleeding, organ impairment, and shock.

There are four serotypes; exposure to one serotype provides lifelong immunity to that type. Previous infection with one serotype may predispose an individual to a more severe infection with another serotype. Thus, severe dengue is more common in indigenous individuals than the previously unexposed traveler. The diagnosis is primarily clinical. The presence of thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and hemoconcentration is suggestive, and confirmatory tests with PCR or immunoglobulin M antibodies via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are available.

Supportive therapy is the only treatment available, with a focus on fluid repletion. Patients with mild illness are treated as outpatients. Admission of those with severe illness, hemorrhagic manifestations, shock, or an uncertain diagnosis is warranted.

Consider dengue fever in recently returned travelers with fever, headache, and myalgias, particularly travelers from the Caribbean or Southeast Asia.

The fever tends to be high and may suddenly resolve and then return, also known as a “saddle back” fever pattern.

A positive “tourniquet test” is suggestive of dengue. A blood pressure cuff is applied and inflated to a point between the systolic and diastolic pressures for 5 minutes. The test is positive if there are more than 20 petechiae per square inch.

Occasional cases of dengue occur in South Texas and an outbreak recently occurred in Key West, Florida.

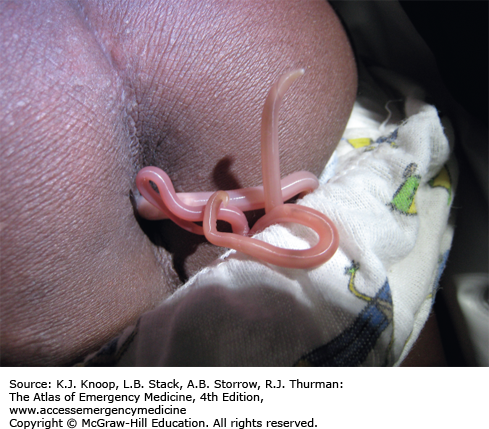

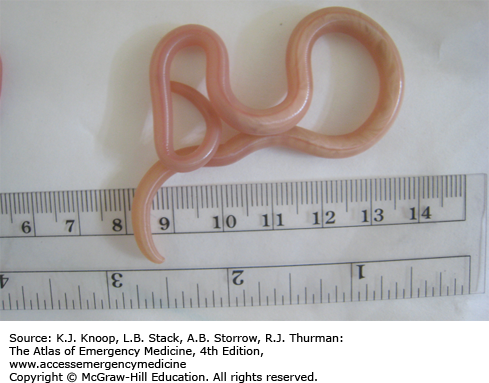

DRACUNCULIASIS

Dracunculiasis is a debilitating roundworm infection caused by Dracunculus medinensis, commonly known as the Guinea worm. Dracunculiasis was historically widespread throughout equatorial Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia but the disease is now isolated to limited areas of Africa due to intensive eradication efforts. Dracunculiasis has a complex life cycle beginning when infected water fleas, or cyclops, are ingested while drinking from unclean water sources. Following ingestion, the larval worm penetrates through the stomach and intestine and migrates to the subcutaneous tissue, where it matures and reproduces. A painful wound develops, usually on the lower extremity, when the female emerges to release larvae. Immersion in water relieves the pain, allowing the worm to release larvae and complete the life cycle.

Emergence of the worm leads to a painful wound that is often accompanied by fever, nausea, vomiting, edema, intense pruritus, ulceration, and eosinophilia, all of which can last for months. The wounds often become secondarily infected, leading to significant disability. Drinking boiled or filtered water prevents dracunculiasis.

The worm is carefully extracted, usually around a stick or rolled gauze, in order to avoid retained worm products and the resultant inflammatory reaction. This process can take days to weeks. Daily immersion in water, with proper disposal to avoid larval spread, helps facilitate worm removal. Surgical excision is possible.

The Guinea worm is the largest tissue parasite of humans. While very thin (2 mm in diameter), a full-grown worm is about a meter in length.

Dracunculiasis is rarely fatal, but the wound can cause significant morbidity and economic loss in areas with high infection rates.

It is predicted that dracunculiasis will be the first parasitic disease to be fully eradicated, largely through patient education and use of filtered water.

ELEPHANTIASIS

Elephantiasis affects more than 120 million people worldwide with over 40 million severely disfigured. It is not a specific disease, but rather a syndrome caused by chronic obstruction of lymphatics. The most common cause is lymphatic filariasis, which is caused by the thread-like worms Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. The infection is transmitted to humans by mosquitoes. Adult worms lodge in the lymphatics, disrupting the fluid balance between tissues and blood vessels, causing lymphedema of the extremities, breast, or genitourinary (GU) system. The infection is generally acquired in childhood, although clinical manifestations may take years to develop. Adult worms live 4 to 6 years, producing millions of blood circulating microfilariae. Acute symptoms of lymphadenopathy and dermal inflammation may precede and later accompany chronic swelling. With persistent infection and inflammation, the skin develops a hyperkeratotic, pebbly, or warty appearance that may become ulcerated and darkened. Bacterial and fungal superinfections contribute to morbidity.

Mosquito nets and insect repellants are the main means of prevention of lymphatic filariasis. Parasites may be detected microscopically in the blood, but the nocturnal periodicity makes identification challenging. Eosinophilia is common, but is nonspecific. Availability of a rapid card test that identifies circulating antigens has overcome this problem and is available in some endemic areas.

Treatment of lymphatic filariasis depends upon the presence or absence of other filarial organisms and includes various combinations of albendazole, ivermectin, and diethylcarbamazine. Cleansing of the affected areas and topical antibiotics aid in thwarting secondary disease. Local massage and elevation of the extremity improve lymphatic flow.

Elephantiasis bears a heavy social burden due to physical limitations, disfigurement, sexual disability, and social stigmatization. Affected patients may be shunned by their families, are often unwed, and unable to work.

Testicular hydrocele is the most common manifestation of chronic W bancrofti infection for males in endemic areas.

Symptomatic filariasis is occasionally seen in travelers, even in those with only short-term stays in endemic regions.

W bancrofti occasionally causes an acute asthma-like condition known as tropical pulmonary eosinophilia.

Podoconiosis is a noninfectious cause of elephantiasis that occurs in people who walk barefoot in areas with large amounts of volcanic ash. Kaposi sarcoma is another emerging cause of nonfilarial elephantiasis in sub-Saharan Africa.

EPIDEMIC MENINGITIS

Meningococcal disease in developed countries usually consists of sporadic cases and small outbreaks. In contrast, massive epidemics of serogroup A or C meningococcal meningitis occur in tropical countries, most notably in sub-Saharan Africa. These seasonal outbreaks tend to occur during the dry season along a wide swath of equatorial Africa known as the “meningitis belt.”

The clinical presentation of epidemic meningitis is the same as in developed countries. Patients will typically present with fever, headache, nausea/vomiting, photophobia, and neck stiffness. Coma and death typically ensue if not treated. Diagnosis is with a spinal tap, although patients in resource-limited countries are often treated based on clinical grounds during a known outbreak. Mortality rates of less than 10% are obtainable. Large-scale vaccination programs are effective in decreasing spread of the disease within the affected areas and in adjacent population centers.

The mainstays of treatment are antibiotics and supportive care. Penicillins, cephalosporins, and ampicillin are still the treatments of choice in many settings, and are usually efficacious.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree