Stage

Serum creatinine

Urine output

1

1.5–1.9 times baseline

OR

≥0.3 mg/dl (>26.5 μmol/l) increase

<0.5 ml/kg/h for 6–12 h

2

2.0–2.9 times baseline

<0.5 ml/kg/h for ≥12 h

3

3.0 times baseline

OR

Increase in serum creatinine to ≥4.0 mg/dl (353.6 μmol/l)

OR

Initiation of renal replacement therapy

OR, In patients <18 years, decrease in eGFR to <35 ml/min per 1.73 m 2

<0.3 ml/kg/h for ≥24 h

OR

Anuria for ≥12 h

Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) is commonly used as a marker for AKI, despite being affected by many non-renal factors (protein intake, catabolic state, volume status etc.). The ratio of BUN to SCr, similarly to urine chemistry (fractional excretion of sodium and urea) and urine microscopy are useful tools for workup of AKI. Nonetheless, BUN, urine studies and kidney biopsy are rarely helpful in establishing the diagnosis of AKI in clinical practice.

Despite the usefulness of RIFLE, AKIN and KDIGO criteria, clinical judgment remains a key component of AKI diagnosis. Diagnostic criteria provide a “frame of reference” for the clinician and are essential for large epidemiological studies and quality improvement projects. Nevertheless, those criteria do not take into account the patient’s clinical course and response to therapy, which are often key to establishing or refuting the diagnosis of AKI.

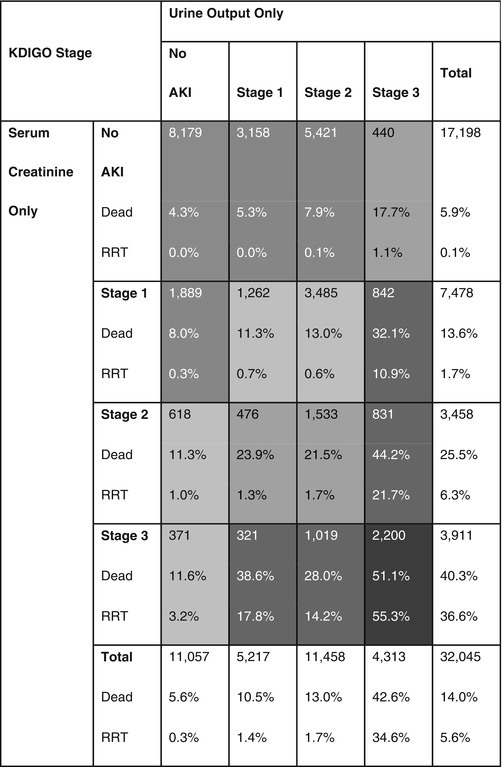

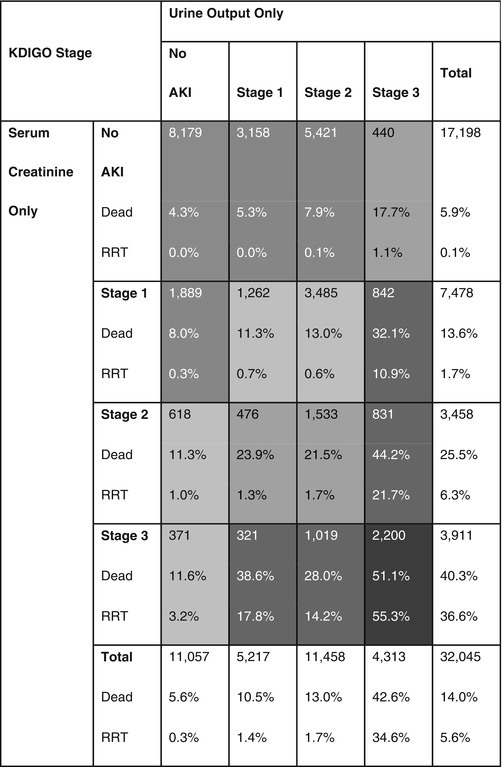

Relationship Between Serum Creatinine and Urine Output

Several studies have demonstrated that oliguric AKI carries a worse prognosis compared to non-oliguric AKI. In other words, the presence of the two components of the definition of AKI is associated with worse outcomes [3, 8]. Isolated oliguria without subsequent increase in SCr still appears to be associated with a decrease in 1-year survival [8]. These results further validate the role of urine output in diagnosing and staging of AKI (Table 42.2).

Table 42.2

Relationship between urine output and serum creatinine criteria and clinical outcomes

Differentiating Between AKI and CKD

Renal ultrasonography is a useful tool for differentiation of CKD from AKI. When no information about baseline renal function is available, findings such as a small kidney size and an increased echogenicity of the renal cortex compared to the liver parenchyma are good surrogates of chronic irreversible kidney disease [9]. The caveat here is that one cannot rule out superimposed AKI on CKD. Nevertheless, this remains useful information in diagnosing and classifying the severity of AKI. Oliguria and anuria are suggestive of AKI. Other parameters such as serum calcium and phosphorus, intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) levels and hemoglobin are less helpful for differentiation between AKI and CKD. A group in Turkey suggested that setting the cutoff for intact PTH as 170 pg/mL or more could be a sensitive and specific way to distinguish CKD from AKI [10].

Clinical Use of Novel Biomarkers

There is currently a multitude of well-validated biomarkers that are able to predict, diagnose early, differentiate the severity and provide information on the course and outcomes of AKI. Despite reasonable performance, these biomarkers have yet to become established in clinical practice, despite their availability in certain regions of the world [11, 12]. The 10th Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) meeting in 2014 examined the discrepancy between the number of biomarkers that have been validated and their limited clinical application till this moment [13]. Ideally, “damage biomarkers” should be incorporated with “functional biomarkers” (such as urine output, SCr) to improve management of AKI. Incorporation of AKI biomarkers, or possibly a combination of those biomarkers, into clinical tools (such as the incorporation of cardiac troponins in the TIMI risk score for unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction) that will guide management of AKI is the next step for those biomarkers. Cost is also a consideration, but the costs associated with current practice, which often includes testing such as urine chemistries, must also be considered. Finally, the costs associated with delayed recognition of AKI are also likely to be considerable. In late 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration announced the clearance of the first biomarker for AKI, urine [TIMP-2] [IGFBP7] (trade name NephroCheckTM). The extent to which this test changes the existing paradigm is still unknown but the test characteristics are superior to previous markers [10].

Evidence Contour

Some questions surrounding the diagnosis of AKI remain subject for debate and for further investigation.

Determining Baseline Serum Creatinine

KDIGO guidelines emphasize the use of relative changes in SCr rather than absolute numbers for diagnosis and classification of AKI. Determining baseline SCr is therefore a necessary step to the diagnosis of AKI. It is not uncommon that information about baseline renal function is not available, especially upon initial evaluation of critically ill patients. The ADQI group suggested that an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 75 ml/mn/1.73 m2 be assumed for such patients and calculating their baseline SCr using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula [6]. The problem with this method is that CKD is one of the most important risk factors for AKI [14], and assuming that patients with AKI have a near-normal baseline eGFR will under-estimate their baseline SCr and therefore over-estimate the incidence of AKI [15]. Using this method in the case example would have resulted in overestimation of the severity of AKI by assuming a normal eGFR at baseline. Thus, this method should be avoided in patients with a suspicion of CKD. Conversely, using the minimum inpatient SCr or the admission SCr tends to underdiagnose AKI and is also suboptimal [15]. Multiple imputation is a commonly used method in statistical analyses that uses known patient characteristics to estimate missing data points. This method has shown promise in its ability to determine baseline SCr in a more accurate way [16], but is not widely used in clinical practice to this date. Currently the best method will depend on the patient in question and require clinical judgment.

Imaging Techniques for Diagnosis of AKI

Several studies have examined the utility of resistive indices (RI) through renal Doppler ultrasonography in diagnosing or predicting AKI prior to alteration of functional markers such as urine output and SCr [17–19]. Unfortunately, resistive indices are affected by a wide variety of factors [20, 21], which limits their specificity and usefulness in the clinical setting. Assessing kidney function or GFR through imaging is also an appealing idea, as information about the structure, perfusion and differential function of both kidneys may also be obtained. Functional magnetic resonance (functional MR) imaging is a promising tool for evaluation of glomerular filtration rate and renal oxygenation but is limited by need for exogenous contrast media and is still largely experimental [22]. Real-time GFR measurement using fluorescent markers is also a promising method but is still limited to animal models of AKI [23–25]. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) is a new technique that can identify alterations in renal perfusion and has been applied in renal transplantation to differentiate between rejection and acute tubular necrosis. CEUS has yet to be validated for AKI in the ICU setting [26].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree