151 Toxic Alcohols

• Toxic alcohol poisoning may initially be mistaken for simple inebriation.

• Untreated ethylene glycol poisoning may result in renal failure.

• Untreated methanol poisoning may result in blindness.

• Acidosis from ethylene glycol or methanol may not be evident until several hours after exposure.

• An osmol gap may not be evident in patients whose presentation to the emergency department is delayed, and these patients benefit from early dialysis.

• An osmol gap measurement is only a screening test and is never diagnostic like a quantitative alcohol measurement.

• Isopropanol poisoning classically results in an elevated osmol gap without significant acidosis.

• Treatment with ethanol or fomepizole should be considered in cases of a witnessed ingestion of a toxic alcohol, when such an ingestion is highly suspected from the history, in the presence of an enlarged osmol gap alone with appropriate clinical suspicion, in the patient with both an enlarged osmol gap and anion gap acidosis, or when the serum concentration of a toxic alcohol exceeds 20 mg/dL.

• Early alcohol dehydrogenase inhibition minimizes metabolism of the toxic alcohol to organic toxic acids and reduces alcohol-specific complications.

Epidemiology

Except for ethanol, no other alcohols are fit for human consumption, and they are properly termed toxic alcohols. Ethylene glycol, methanol, and isopropanol are the most common toxic alcohols associated with human poisoning.1 Less commonly reported but still clinically important toxic alcohols are propylene glycol, diethylene glycol, and other glycol ethers. Unintentional ingestion from a mislabeled or contaminated container occurs commonly in children, whereas intentional ingestion of a toxic alcohol as an ethanol substitute or for self-harm occurs more commonly in adults. If untreated, toxic alcohol poisoning can result in metabolic acidosis, renal failure, blindness, central nervous system (CNS) injury, pulmonary edema, or death.

Ethylene glycol is present in antifreeze solutions, deicing solutions, foam stabilizers, and chemical solvents.2 Methanol is a component of windshield-washing solutions, gas-line antifreeze solutions, solvents, and brake cleaners.3 Isopropanol is found in rubbing alcohol, aerosols, and other cosmetic products. Propylene glycol is commonly found as a diluent in parenteral medications such as phenytoin, diazepam, and lorazepam.4 The other toxic glycols can be found in various household and industrial cleaners, paints, resins, and solvents.

More than 35,000 toxic alcohol exposures are reported yearly to the American Association of Poison Control Centers.1 Most cases are individual poisonings. However, contamination of beverages or pharmaceutical products has resulted in epidemic poisonings, including two significant outbreaks, in India and in Haiti in the 1990s, from diethylene glycol that affected hundreds of victims.5

Definitive laboratory confirmation of toxic alcohol poisoning is usually not immediately available to the emergency physician. However, early recognition of poisoning and emergency department (ED)–initiated interventions significantly improve patient outcomes and reduce the occurrence of alcohol-specific complications.6

Pathophysiology

Most toxic alcohol poisonings occur by oral ingestion. Significant methanol poisoning has also been reported to occur by inhalation of brake cleaning products, and isopropanol poisoning has occurred through transcutaneous absorption in children treated for fevers at home with rubbing alcohol baths.7,8 Complete absorption is rapid by any route, each alcohol has a small volume of distribution (0.5 to 0.8 L/kg), and metabolism to toxic organic by-products occurs through hepatic alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) (Figs. 151.1 and 151.2).

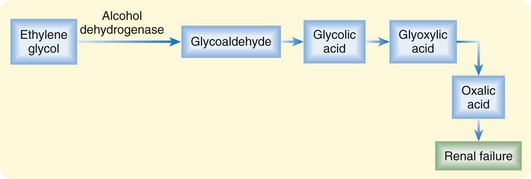

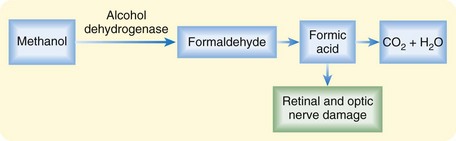

Toxicity from the parent products is limited to local mucous membrane irritation and CNS depression. The term toxic is specifically related to the production of different toxic by-products (oxalic acid and formic acid) by each of these alcohols. Ethylene glycol metabolism results in renal failure from deposition of oxalic acid in renal tubules.2 Methanol metabolism to formic acid results in blindness from direct injury to the retinal and optic nerves.3

Because the rate of metabolism through ADH varies by alcohol type and by individual variability in cytochrome P-450 genetic expression, clinical onset of worrisome symptoms can be delayed by 1 to 36 hours.2,3 Furthermore, the concomitant presence of ethanol may delay metabolism to the toxic by-products because ethanol has a higher affinity for ADH than the toxic alcohols and competitively inhibits metabolism of these alcohols to toxic by-products until the serum ethanol concentration drops to less than 100 mg/dL.

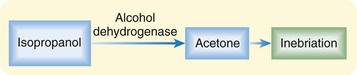

Isopropanol is unlike ethylene glycol and methanol in that it is not metabolized to an organic acid. Instead, it is metabolized to acetone, an osmotically active CNS depressant, which leads to profound inebriation (Fig. 151.3).8

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classic or Typical

Most patients poisoned with a toxic alcohol demonstrate some level of CNS depression consistent with inebriation (Table 151.1). Patients who arrive in the ED either shortly after a large ingestion or later after an ingestion, such that systemic accumulation of toxic metabolites has occurred, may be obtunded on presentation or may become obtunded during ED evaluation. The level of inebriation does not correlate with peak serum concentrations of the parent product or the accumulation of metabolic by-products.

Table 151.1 Symptoms and Signs of Toxic Alcohol Poisoning

| Symptoms | |

| Signs |

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis mnemonic “A CAT MUD PILES” should be used for any patient in whom ED evaluation demonstrates an anion gap acidosis (Box 151.1). Many of the possible conditions in the list can be easily excluded with a basic metabolic profile (e.g., uremia) and rapidly obtainable serum quantitative tests (e.g., salicylate). Although alcoholic ketoacidosis looks like toxic alcohol poisoning, it improves rapidly with only intravenous fluids and dextrose supplementation, whereas acidosis from a significant toxic alcohol exposure does not improve without antidotal treatment or enhanced elimination with hemodialysis, or both. In children, disorders of organic acid metabolism should be considered when poisoning is unlikely or has been excluded.