180 Tick-Borne Diseases

• Many patients with tick-borne diseases (TBDs) do not recall a tick bite; the history should focus on activities that predispose to tick exposure.

• Because some of the TBDs are fatal if untreated, consider these diseases in patients with fever of unknown source, especially in “tick season.”

• TBDs most often can be strongly suspected or diagnosed clinically, and treatment should be initiated before definitive laboratory confirmation.

Epidemiology

Because these illnesses frequently occur in the absence of a known tick bite, physicians must consider TBDs when patients present in the correct epidemiologic context and with a recognizable syndrome. This chapter considers these diseases in syndromic groups (patterns of presentation), rather than individually. Individual TBDs are listed in Table 180.1 (North America) and Table 180.2 (worldwide). Travelers may import the TBDs from one location to another.

Table 180.1 Tick-Borne Diseases of North America

| DISEASE | PATHOGEN OR AGENT | MAJOR TICK VECTOR |

|---|---|---|

| Lyme disease | Borrelia burgdorferi | Ixodes scapularis, others |

| Babesiosis | Babesia microti | Ixodes scapularis |

| Anaplasmosis, granulocytic | Anaplasma phagocytophilum | Ixodes scapularis |

| Anaplasmosis, monocytic | Ehrlichia chaffeensis | Amblyomma americanum |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Rickettsia rickettsiae | Dermacentor variabilis |

| Tularemia | Francisella tularensis | Dermacentor variabilis, Dermacentor andersoni, and Amblyomma americanum |

| Relapsing fever | Borrelia species (various) | Ornithodoros species |

| Colorado tick fever | Coltivirus | Dermacentor andersoni |

| Tick paralysis | Neurotoxin | Dermacentor variabilis, others |

| Q fever | Coxiella burnetii | Dermacentor variabilis |

Table 180.2 Other Important Tick-Borne Diseases Worldwide

| DISEASE | PATHOGEN OR AGENT | MAJOR TICK VECTOR |

|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean spotted fever | Rickettsia conorii | Rhipicephalus sanguineus |

| Other spotted fevers | Other rickettsial species | Varies |

| Tick-borne encephalitis | Flavivirus | Ixodes ricinus, others |

| Relapsing fever | Various Borrelia species | Various Ornithodoros species |

Pathophysiology and Tick Anatomy

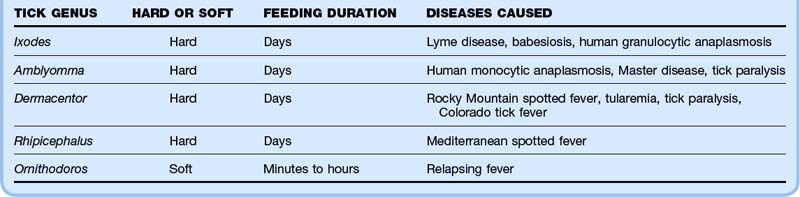

Two families of ticks are important in human TBDs. Hard (Ixodidae) ticks tend to attach and feed for days, whereas soft ticks (Argasidae) feed in minutes to hours. Table 180.3 lists some characteristics of these different types of ticks. Because the hard ticks, which transmit most of the human TBDs, feed for so long, tick removal during the first 24 hours of attachment provides one strategy for disease prevention, a concept best studied in the context of Lyme disease. Figures 180.1 to 180.3 show various stages of Ixodes scapularis, Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum ticks.

Fig. 180.2 A Dermacentor variabilis tick next to an Ixodes scapularis tick.

(Photograph by Darlyne Murawski.)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

TBDs most commonly manifest as one of four syndromes (Table 180.4):

• Localized rash (with or without fever)

• Febrile illness without prominent rash

• Febrile illness with diffuse rash

Table 180.4 Tick-Borne Disease Syndromes

| SYNDROME | DISEASE | CHARACTERISTICS OF TYPICAL CASES |

|---|---|---|

| Localized rash (without or without fever) | Erythema migrans (Lyme disease) Tularemia (ulceroglandular) | Large, flat, red rash, sometimes with central clearing at the site of the tick bite Shallow ulcer, usually acral at the site of the tick bite, associated with regional lymphadenopathy |

| Febrile illness without rash | Anaplasmosis Babesiosis Lyme disease Rocky Mountain spotted fever Tularemia Q fever Colorado tick fever | High fever, chills, headache, myalgias High fever, chills, headache, fatigue, myalgias Flulike illness without respiratory or gastrointestinal manifestations Severe headache, fever, myalgias High fever without localizing findings except respiratory symptoms in tularemic pneumonia Nonspecific febrile illness Fever (saddle-back curve), headache, myalgias |

| Febrile illness with generalized rash | Rocky Mountain spotted fever Lyme disease Anaplasmosis | As above with rash; rash beginning as maculopapular, then possibly evolving into petechial and skin necrosis Multiple erythema migrans lesions (smaller, no punctum, less complexity than primary erythema migrans lesions) Nonspecific maculopapular rash |

| Acute neurologic illness | Tick paralysis | More commonly in children, especially in young girls with the tick embedded in the scalp |

Localized Rash (With or Without Fever)

Erythema migrans (EM), the rash of early localized Lyme disease, is an important condition that emergency physicians should be familiar with because antibiotic treatment at this stage almost always leads to excellent outcomes. Lyme disease is by far the most common vector-borne illness in North America. EM develops at the site of the tick bite roughly 7 to 10 days later (range, 3 to 33 days), usually as flat erythema that is neither pruritic nor painful, although it can be either. The classic description of a target or bull’s-eye lesion with central clearing is not the most common. Most EM rashes are uniformly red. EM can be darker in the center, vesicular, or necrotic. Know the spectrum of morphology of EM to avoid misdiagnosis of this infection (Figs. 180.4 to 180.6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree